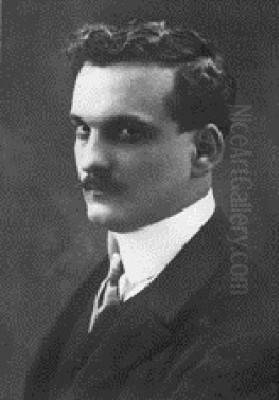

Julio Romero de Torres stands as one of Spain's most distinctive and popular painters from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Born in Córdoba on November 9, 1874, and passing away in his beloved hometown on May 10, 1930, his life and art were deeply intertwined with the culture, traditions, and mystique of Andalusia. His work, a unique blend of meticulous Realism, evocative Symbolism, and elements drawn from Spanish artistic traditions, primarily focused on the portrayal of women, capturing a complex vision of Andalusian identity that continues to resonate.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Córdoba

Julio Romero de Torres was immersed in art from his earliest days. His father, Rafael Romero Barros, was a notable painter himself and the director and founder of Córdoba's Provincial Museum of Fine Arts (Museo de Bellas Artes de Córdoba) and the School of Arts. This environment provided Julio and his siblings, some of whom also became artists, with an unparalleled artistic education. He formally studied at the School of Fine Arts under his father, quickly demonstrating exceptional talent.

His early works showed a strong grounding in the Realist tradition prevalent in Spanish art at the time, influenced by the academic training he received. He also displayed an early interest in music, an element that would subtly inform the rhythm and mood of his later paintings. Local competitions and exhibitions provided platforms for his burgeoning skills; he won awards at the Provincial School and the Athenaeum (Ateneo) in Córdoba, signaling the arrival of a significant talent. His initial output often depicted local scenes and types, aligning with the Costumbrista tradition focused on regional customs and manners.

The influence of earlier Spanish masters was also formative. The dramatic lighting and psychological depth found in the works of Francisco Goya, and the classical compositions and dignity of figures by Diego Velázquez, provided historical anchors. Furthermore, the landscape paintings of Aureliano de Beruete, a key figure in Spanish Impressionism and Realism, offered a model for capturing the specific light and atmosphere of Spain, although Romero de Torres would ultimately forge a path distinct from pure landscape or Impressionistic concerns.

The Evolution Towards Symbolism and Modernismo

While rooted in Realism, Romero de Torres's style evolved significantly as he absorbed contemporary European artistic currents, particularly Symbolism and the aesthetics associated with Modernismo, the Spanish variant of Art Nouveau. He traveled, studied, and exhibited, broadening his horizons beyond Córdoba and Madrid. His work began to move away from straightforward depiction towards more ambiguous, emotionally charged, and symbolic representations.

This shift involved integrating Symbolist themes – mystery, spirituality, sensuality, death, and the enigmatic nature of femininity – into his precise, almost photographic technique. Unlike the looser brushwork of many Impressionists, such as his celebrated contemporary Joaquín Sorolla, known for his luminous beach scenes, Romero de Torres maintained a smooth finish and clear delineation of forms. His focus was less on capturing fleeting moments of light and more on constructing carefully staged compositions imbued with deeper meaning.

His engagement with Modernismo can be seen in the decorative qualities of some works, the sinuous lines, and the integration of figures within richly textured settings, often featuring traditional Andalusian crafts like ceramics, leatherwork, and textiles. He shared this interest in blending modern aesthetics with Spanish identity with other artists of his generation, such as Santiago Rusiñol and Ramón Casas in Catalonia, though his focus remained firmly rooted in the south.

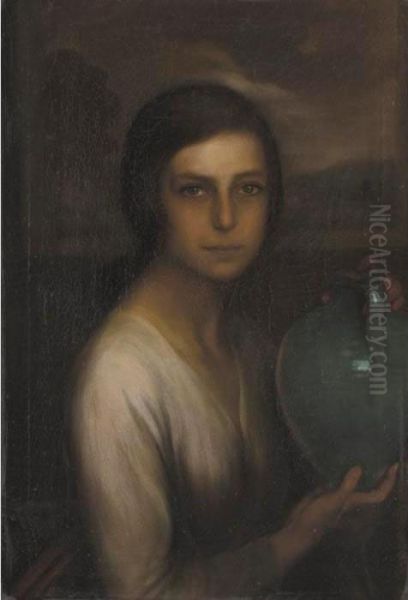

The Andalusian Muse: Women in His Art

The most defining aspect of Julio Romero de Torres's oeuvre is his persistent focus on the female figure, specifically the Andalusian woman. He created an iconic, almost archetypal image: typically dark-haired, dark-eyed women, often depicted with a captivating, melancholic, or mysterious gaze. These figures are not mere portraits; they often embody complex ideas about love, passion, piety, sorrow, and the perceived duality of the female spirit – embodying both sanctity and sin, grace and danger.

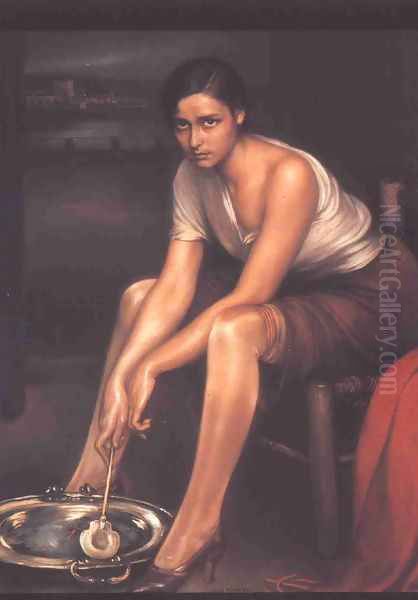

His models were often local women from Córdoba, and he depicted them in settings rich with cultural references: patios adorned with flowers, interiors with traditional furniture, or against backdrops featuring Córdoba's landmarks like the Guadalquivir River or the Roman Bridge. Works like La Chiquita Piconera (The Little Coal Girl, c. 1928-1930) are prime examples. The painting shows a young woman seated pensively beside a brazier, embodying a quiet dignity amidst humble surroundings, with the city subtly visible behind her. It became one of his most famous and reproduced images.

Another iconic work, Mira qué Bonita era (Look How Pretty She Was, 1895), though an earlier piece, already shows his fascination with themes of beauty, mortality, and Andalusian identity. The painting depicts a deceased young woman laid out, mourned by others, capturing a poignant blend of traditional mourning rituals and a meditation on transient beauty. He often used props like guitars, fans, mantillas, and oranges – symbols deeply associated with Andalusian culture – to enrich the narrative and symbolic layers of his paintings.

His portrayal of women sometimes courted controversy, seen by some as perpetuating stereotypes of the exotic or fatal Andalusian female. However, his approach was often more complex, exploring the social roles, inner lives, and symbolic weight attributed to women within Spanish society at the time. He presented them with a distinct presence and psychological depth, inviting viewers to contemplate their enigmatic expressions.

Allegory, Symbolism, and Major Works

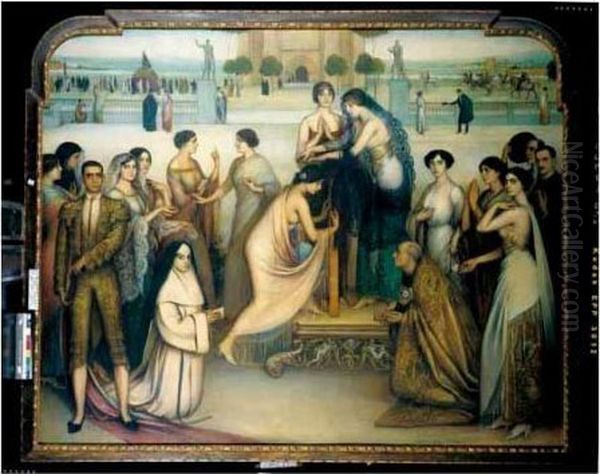

Beyond portraits and genre scenes, Romero de Torres excelled in creating complex allegorical paintings. These works often synthesized his key themes – Andalusia, femininity, love, death, religion, and art itself – into elaborate compositions. Poema de Córdoba (Poem of Córdoba, c. 1913-1915) is a monumental polyptych that serves as an allegory of the city, featuring numerous figures representing its history, culture, and spirit, including past luminaries and symbolic female figures.

Works like Amor Sagrado y Amor Profano (Sacred Love and Profane Love) directly tackle the duality he often explored, presenting contrasting female figures within a symbolic landscape. Similarly, La Gracia (Grace) and El Pecado (Sin) form a powerful pair, exploring themes of virtue and temptation through idealized female nudes in allegorical settings, demonstrating his ability to blend classical themes with his distinctive style.

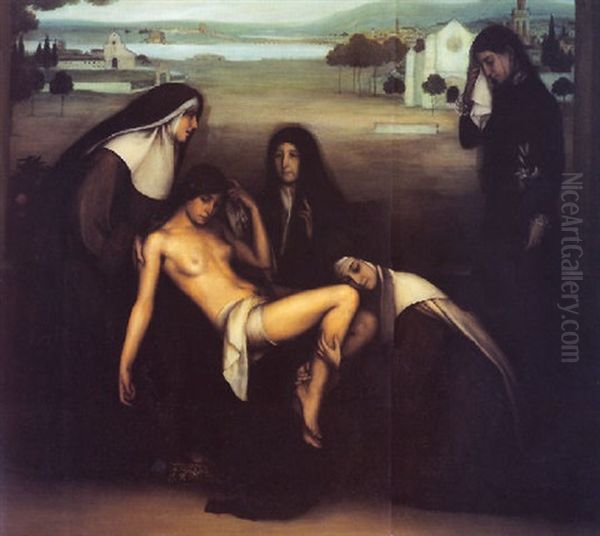

His use of symbolism was rich and varied. The guitar could represent folk culture and passion; oranges, fertility and the Andalusian landscape; religious imagery, the deep Catholic roots of the region; and depictions of death or mourning figures, a typically Spanish preoccupation with mortality. This symbolic language connected his work to the broader European Symbolist movement, which included artists like Gustav Klimt in Vienna, whose decorative patterns and focus on the femme fatale offer points of comparison, or the French and Belgian Symbolists exploring similar themes of interiority and mysticism.

La Consagración de la Copla (The Consecration of the Copla, 1911-1912), an ambitious work celebrating Andalusian folk song (the copla), became a focal point of controversy. Its rejection from the National Exhibition of Fine Arts in Madrid in 1915 caused a public outcry and solidified Romero de Torres's status as a popular, anti-establishment figure, beloved by the public even when official circles were hesitant.

Technique, Palette, and Artistic Process

Julio Romero de Torres developed a highly refined and distinctive painting technique. He favored smooth surfaces, often painting on panel or fine canvas, allowing for meticulous detail. His drawing was precise, underpinning the solid structure of his compositions. While influenced by photography in its clarity, his work transcends mere photorealism through its carefully controlled atmosphere and symbolic content.

His palette is often characterized by dark, earthy tones – deep browns, ochres, blacks, and greens – which lend a somber and mysterious quality to many works. However, these are frequently punctuated by vibrant accents: the rich color of a shawl, the bright hue of flowers, the gleam of jewelry, or the warm flesh tones of his figures. This contrast enhances the visual impact and draws attention to key elements within the composition.

He masterfully employed light and shadow, often using a form of modern chiaroscuro to model figures and create dramatic or intimate moods. The lighting in his paintings rarely feels purely naturalistic; instead, it seems carefully orchestrated to highlight expressions, textures, and symbolic objects, contributing to the overall sense of staged reality and psychological intensity. His studio practice involved careful preparation, studies, and working with models to achieve the precise effects he desired.

His background, including teaching clothing and drapery painting at the School of Fine Arts in Madrid from 1916, likely contributed to his exceptional skill in rendering textiles. The textures and patterns of shawls, dresses, and mantillas are often depicted with extraordinary detail and tactile quality, becoming important compositional and symbolic elements in their own right.

Career, Recognition, and Cultural Milieu

Throughout his career, Julio Romero de Torres actively participated in the Spanish art world and gained significant recognition, both nationally and internationally. He regularly submitted works to the National Exhibitions of Fine Arts in Madrid, winning medals in 1899 and 1904, although he also faced rejections, as noted with La Consagración de la Copla. His participation in international exhibitions, such as the one in Buenos Aires in 1910, helped spread his fame beyond Spain.

His studio in Madrid became a gathering place for artists, writers, and intellectuals, reflecting his integration into the vibrant cultural life of the capital. He maintained connections with prominent figures of the time, including the writer Ramón del Valle-Inclán, with whom he collaborated on the film La Malcasada (1926), demonstrating an interest in new media. He was also associated with poets like the Machado brothers (Antonio and Manuel), who shared an interest in capturing the essence of Spanish identity and landscape.

His relationship with contemporaries like Joaquín Sorolla was complex. While both were leading figures, their styles and thematic concerns differed significantly – Sorolla's sun-drenched Valencian optimism contrasting with Romero de Torres's darker, more introspective Andalusian focus. Another important contemporary was Ignacio Zuloaga, who, like Romero de Torres, focused on Spanish themes and types, often with a somber or dramatic intensity, but whose style was rougher and more expressionistic.

A trip to Argentina in 1922 proved a major triumph, with exhibitions of his work receiving enthusiastic acclaim, cementing his reputation in Latin America. Despite occasional friction with the official art establishment, Romero de Torres achieved widespread popularity. His images, particularly La Chiquita Piconera, became deeply ingrained in Spanish popular culture, reproduced on posters, calendars, and various commercial items, sometimes simplifying his complex vision but testifying to its broad appeal.

Legacy and Influence

Julio Romero de Torres left a significant and complex legacy. He created a powerful and enduring visual representation of Andalusia, particularly its women, that shaped both internal and external perceptions of the region. His unique fusion of academic Realism, Symbolism, and Costumbrismo secured him a distinct place in Spanish art history, bridging the 19th-century traditions and the emerging modern movements.

His direct influence on subsequent generations of painters is perhaps less pronounced than that of innovators like Picasso or Miró. Some later artists reacted against what they saw as the folkloric or overly sentimental aspects of his work. However, his technical mastery and his commitment to figurative painting provided a touchstone for Spanish artists who continued to explore realism and portraiture throughout the 20th century. His exploration of psychological depth within a realistic framework also resonates with aspects of later figurative art.

More broadly, his work contributed significantly to the cultural identity discourse in Spain during the early 20th century, a period when artists and intellectuals were grappling with questions of tradition, modernity, and national character. His paintings remain potent symbols of Córdoba and Andalusia, celebrated in his dedicated museum and continuing to attract scholarly and popular interest. He demonstrated that traditional themes and techniques could be infused with modern sensibilities and psychological complexity.

Major Collections

The most important collection of Julio Romero de Torres's work is housed in the museum dedicated to him, the Museo Julio Romero de Torres, located in the Plaza del Potro in Córdoba, adjacent to the Fine Arts Museum his father once directed. This museum holds many of his most iconic paintings, including La Chiquita Piconera, Nuestros Ángeles en el Cielo (Our Angels in Heaven), and Cante Hondo (Deep Song).

Significant works can also be found in other major Spanish institutions. The Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid holds works like Lectura (Reading). The Carmen Thyssen Museum in Málaga owns pieces such as La Feria de Córdoba (Córdoba Fair). The Museo de Bellas Artes de Córdoba also retains a collection, reflecting his deep ties to the city.

While perhaps less represented than in Córdoba, works occasionally appear in or are held by other prestigious museums like the Prado Museum in Madrid (which historically focused on earlier masters but holds some relevant works from the period) and the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum. His presence in these collections underscores his importance within the canon of Spanish art. Private collections in Spain and abroad also hold numerous examples of his work.

Conclusion

Julio Romero de Torres remains a fascinating and somewhat enigmatic figure in Spanish art. Deeply rooted in his native Córdoba, he absorbed and transformed artistic influences ranging from the Spanish Golden Age masters to contemporary European Symbolism. His meticulous technique, combined with a profound interest in the culture and people of Andalusia – particularly its women – resulted in a body of work that is both instantly recognizable and layered with meaning.

While sometimes criticized for leaning towards folklorism, his best works transcend mere regional depiction, offering complex meditations on beauty, love, spirituality, and mortality, all filtered through a distinctly Andalusian lens. He captured a specific moment in Spanish cultural history, reflecting its tensions between tradition and modernity, the local and the universal. The enduring popularity of his images and the continued fascination with his enigmatic female figures testify to the unique power and lasting appeal of his art.