Jacopo Chimenti, more famously known as Jacopo da Empoli after his father's birthplace, stands as a significant figure in the Florentine art scene of the late 16th and early 17th centuries. Born in Florence on April 30, 1551, and passing away in the same city on September 30, 1640, Empoli's long and productive career witnessed and contributed to the pivotal transition from the waning complexities of Mannerism to the burgeoning clarity and naturalism of the early Baroque. His work, deeply rooted in Florentine artistic traditions, nevertheless carved a distinct path characterized by directness, devotional sincerity, and a remarkable eye for the tangible world.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Jacopo Chimenti's artistic journey began in Florence, the cradle of the Renaissance, a city still rich with the legacy of its past masters. His initial training took place in the workshop of Maso da San Friano, a respected painter active in the mid-16th century. Maso, whose own style reflected the prevailing Mannerist tendencies, would have provided Empoli with a solid grounding in the techniques and aesthetic sensibilities of the period. This apprenticeship was crucial, as it immersed the young artist in the practical aspects of painting, from preparing pigments and panels to mastering draftsmanship and composition.

Beyond the direct tutelage of Maso da San Friano, Empoli, like many aspiring artists of his time, dedicated himself to studying and copying the works of earlier Florentine giants. Chief among these was Andrea del Sarto, the "faultless painter," whose harmonious compositions, subtle sfumato, and graceful figures left an indelible mark on Empoli. This practice of copying was not mere imitation but a profound form of learning, allowing Empoli to internalize the principles of design, color, and emotional expression that characterized High Renaissance art. While rumors circulated about a possible collaboration with Giorgio Vasari, the influential painter, architect, and art historian, concrete evidence to support this claim remains elusive. Vasari, a dominant figure in Florentine art and a key proponent of Mannerism, would certainly have been a known quantity to Empoli, but their direct professional association is unconfirmed.

The Florentine Artistic Milieu: Responding to Mannerism

To understand Empoli's artistic trajectory, it is essential to consider the prevailing artistic climate of late 16th-century Florence. Mannerism, which had evolved from the High Renaissance, often emphasized elongated figures, complex and sometimes ambiguous compositions, artificial color palettes, and a sophisticated, courtly elegance. Artists like Pontormo and Bronzino had pushed Florentine art in this direction, creating works of great intellectual and aesthetic refinement. However, by the latter half of the century, a counter-movement began to emerge, often referred to as Counter-Mannerism or the Florentine Reform.

This reformist impulse, partly influenced by the Council of Trent's call for clarity and directness in religious art, sought a return to more naturalistic representation, legibility in narrative, and genuine emotional piety. Jacopo da Empoli became a key proponent of this shift. His style consciously moved away from the more "contorted and crowded" aspects of high Mannerism. Instead, he favored a clarity of form and composition that made his narratives accessible and his figures relatable. This approach found parallels in the work of other reform-minded Florentine artists.

Santi di Tito: A Kindred Spirit

A pivotal figure in this artistic reorientation, and one with whom Empoli had significant connections, was Santi di Tito. Santi, older than Empoli, was a leading voice in the call for a more straightforward and naturalistic art. He advocated for a style grounded in observation and clear storytelling, drawing inspiration from the early Renaissance masters as well as contemporary reformist trends. Empoli not only collaborated with Santi di Tito on various projects but also shared a deep stylistic affinity with him. Their works often exhibit a similar commitment to well-defined forms, balanced compositions, and a palette that, while rich, avoided the artificiality of some Mannerist painters. This shared vision contributed significantly to reshaping the artistic landscape of Florence at the turn of the 17th century. Other contemporaries who were part of this broader movement towards reform included Ludovico Cigoli, Gregorio Pagani, and Domenico Passignano, all of whom contributed to a renewed sense of naturalism and emotional directness in Florentine painting.

Stylistic Characteristics: Clarity, Color, and Naturalism

Jacopo da Empoli's mature style is distinguished by several key characteristics. His draftsmanship is confident and precise, defining forms with clarity and avoiding unnecessary embellishment. This clarity extends to his compositions, which are generally well-ordered and easy to read, even when depicting complex multi-figure scenes. He possessed a strong sense of color, often employing rich, saturated hues that lend vibrancy and emotional weight to his paintings. His handling of light and shadow, or chiaroscuro, was adept, used effectively to model figures, create depth, and enhance the dramatic or devotional mood of a piece.

A notable aspect of Empoli's art is its burgeoning naturalism. While he remained indebted to the idealized forms of the Renaissance tradition, particularly in his religious figures, there is a tangible quality to his depictions of textures, fabrics, and, most strikingly, in his still life elements. This naturalistic bent became increasingly prominent throughout his career, reflecting a broader European trend towards greater realism, though Empoli's naturalism was always tempered by a sense of Florentine decorum and grace, distinct from the more rugged realism of artists like Caravaggio in Rome.

Major Works: Religious Narratives

The bulk of Jacopo da Empoli's extensive oeuvre consists of religious paintings, including altarpieces, devotional images, and large-scale narrative scenes. These works were commissioned for churches and religious confraternities throughout Florence and Tuscany, attesting to his high standing and the demand for his particular brand of clear, pious art.

One of his most celebrated altarpieces is Saint Ivo, Protector of Widows and Orphans, housed in the Palazzo Pitti, Florence. This work exemplifies Empoli's ability to convey a scene of compassionate intercession with both dignity and human warmth. Saint Ivo, a 13th-century Breton lawyer canonized for his advocacy for the poor, is depicted listening attentively to the pleas of widows and orphans. The figures are rendered with a solidity and naturalness that makes their plight and the saint's benevolence palpable. The composition is balanced, the colors rich, and the emotional tone one of sincere piety, perfectly aligning with the Counter-Reformation's emphasis on saints as accessible intercessors.

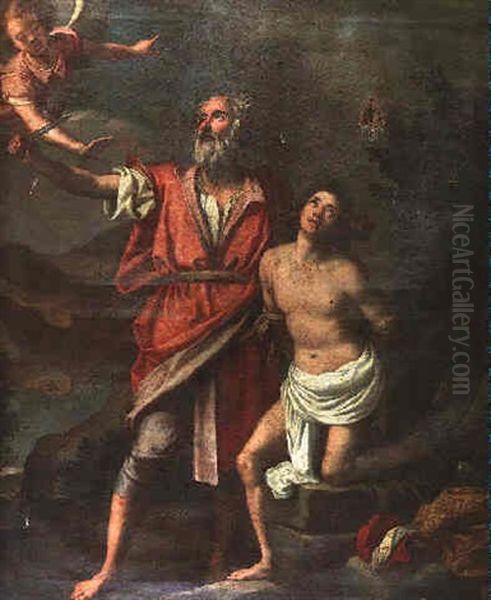

Empoli also undertook significant fresco projects, although his activity in this medium was curtailed later in life. Among his notable fresco cycles were those in the Basilica di San Lorenzo in Florence, where he depicted complex biblical scenes such as the Creation, the Flood, and the Resurrection. These large-scale works demanded considerable skill in composition and execution, further demonstrating his versatility. Another important religious work is the Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian, a subject popular for its dramatic potential and the opportunity to depict the idealized male nude. Empoli's treatment would have focused on the saint's faith and suffering, rendered with his characteristic clarity. His Study for St. Francis in His Assumption reveals his careful preparatory process, focusing on gesture and expression to convey the spiritual ecstasy of the saint.

His Madonnas, often praised for their gentle beauty and tender interaction between Mother and Child, were particularly admired. In these works, his early study of Andrea del Sarto is evident in the softness of the modeling and the harmonious compositions. These devotional images catered to both public and private patrons, reflecting the enduring importance of Marian devotion.

A Pioneer in Still Life

Beyond his religious commissions, Jacopo da Empoli made significant contributions to the genre of still life painting. While still life had appeared as subsidiary elements in larger compositions for centuries, its emergence as an independent genre was a relatively new development in Italy during Empoli's lifetime. His paintings of pantry scenes, laden with game, meats, sausages, fruits, vegetables, and various kitchen implements, are remarkable for their detailed observation and tactile realism.

Works such as Pantry with Cask, Game, Meat and Pottery (sometimes referred to by its inscription "Di Jacopo da Empoli 1624") offer a vivid glimpse into the material culture and culinary abundance of a prosperous Tuscan household. These paintings are not merely inventories of foodstuffs; they are carefully composed arrangements that celebrate the textures, colors, and forms of everyday objects. The glistening skin of a plucked fowl, the rough rind of a melon, the gleam of earthenware – all are rendered with a convincing naturalism. This interest in the tangible world aligns with his nickname, "L’Empilo" (the stewpot), reportedly given to him due to his pronounced love of food. His still lifes can be seen as an artistic expression of this personal passion, transforming humble subjects into objects of aesthetic appreciation. In this, he can be compared to other early Italian still life specialists like Fede Galizia, though Empoli's work in this genre remained more closely tied to the Florentine tradition. His depiction of a "rib-eye steak" in one such painting demonstrates a keen awareness of local culinary specialties, further grounding his art in the specific culture of his time and place.

An Unfortunate Accident and Its Consequences

A significant anecdote from Empoli's life recounts a serious accident: he fell from a scaffold while working on a fresco. This mishap had lasting consequences for his artistic practice. The injuries he sustained reportedly made it impossible for him to continue working in the demanding medium of fresco, which required physical agility and the ability to work at heights for extended periods. While the provided information doesn't specify if he turned to other artistic forms or activities as a direct result, it's clear that this event would have shifted his focus more towards easel painting on canvas or panel, which could be executed in the relative comfort and safety of the studio. This incident underscores the physical risks inherent in large-scale artistic production during this period.

Imitation as Homage: The Shadow of Andrea del Sarto

The profound respect Jacopo da Empoli held for Andrea del Sarto was not merely a student's admiration but a lifelong engagement with the master's style. He was particularly renowned for his ability to emulate del Sarto, especially in his depictions of the Madonna. This was not seen as mere copying but as a skillful channeling of del Sarto's grace and harmony. One specific example of his close study is a drawing in Florence depicting a young man and his hand, which bears a striking resemblance to del Sarto's own drawing style, indicating a meticulous effort to capture the nuances of the master's technique.

Furthermore, Empoli adopted some of del Sarto's studio practices. He is known to have used common studio props, such as chairs and tables, not just as incidental background elements but as tools to help arrange the composition and to fix the poses of his models. This methodical approach, likely learned or inspired by del Sarto's own working methods, contributed to the careful construction and balanced feel of his paintings. This deep engagement with a revered predecessor was a common feature of artistic training and practice, where emulation was a path to mastering the craft and honoring tradition.

Collaborations, Students, and Artistic Circle

Jacopo da Empoli was an active member of the Florentine artistic community. His collaboration with Santi di Tito has already been noted as a significant aspect of his career, reflecting a shared artistic vision. He also reportedly collaborated on some projects with Alessandro Tiarini, a Bolognese painter who spent time in Florence and whose style also evolved towards a more naturalistic and emotionally direct form of Baroque classicism, influenced by artists like Annibale Carracci and his academy in Bologna.

Empoli's studio was also a place of learning, and he trained a number of pupils who went on to have their own careers. Among his notable students were Felice Ficherelli, often called "Il Riposo," known for his sensuous and often dramatic paintings; Giovanni Battista Brazzè (also known as Giovanni Battista Vanni), who became a painter and etcher; and Virgilio Zaballi. Through these students, Empoli's influence extended into the next generation of Florentine artists. His brother, Domenico Chimenti, was also a painter, suggesting a familial involvement in the arts, which likely fostered an environment of artistic exchange and support. His participation in the Accademia del Disegno, Florence's prestigious art academy, would have further embedded him within the city's artistic and intellectual life.

An Innovative Glimpse: Stereoscopic Vision

Intriguingly, Jacopo da Empoli experimented with visual perception in a way that foreshadowed later technologies. He is credited with creating a pair of drawings, each depicting a seated boy from a slightly different viewpoint. These two nearly identical sketches are believed to be an early attempt at producing a stereoscopic image. When viewed appropriately (for instance, with a device that presents each image to a separate eye, or by a "free-viewing" technique), such paired images can create an illusion of three-dimensional depth. This foray into stereopsis demonstrates a curious and innovative mind, exploring the mechanics of vision and representation beyond the conventional concerns of painting. It positions Empoli as an artist interested not only in aesthetic outcomes but also in the scientific principles underlying visual perception, a trait shared by many Renaissance and early modern artists.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Jacopo da Empoli remained active and highly regarded throughout his long career, working well into his eighties. He successfully navigated the changing artistic tides, adapting his style while retaining a core commitment to clarity, craftsmanship, and devotional sincerity. His ability to blend the grace of the Florentine tradition with the emerging desire for greater naturalism and emotional directness ensured his continued relevance and appeal to patrons.

His legacy is multifaceted. As a painter, he produced a substantial body of work that enriched the churches and collections of Florence and beyond. As a teacher, he helped shape the next generation of artists. Perhaps most significantly, he played a crucial role in the transition from late Mannerism to the early Baroque in Florence. He was a reformer who, alongside figures like Santi di Tito, steered Florentine art away from the more esoteric and artificial tendencies of Mannerism towards a style that was more accessible, more natural, and more emotionally engaging. His still lifes, in particular, mark him as an important early contributor to this genre in Italy.

In conclusion, Jacopo da Empoli was more than just a prolific painter; he was a thoughtful and skilled artist who made a lasting impact on the Florentine art world. His dedication to the foundational principles of Florentine design, combined with his openness to new currents of naturalism and his personal explorations into visual phenomena, mark him as a fascinating and important figure. His works continue to be admired for their technical skill, their quiet dignity, and their honest portrayal of both the sacred and the everyday, securing his place as a respected master of his time.