Jacopo Chimenti, more famously known as Jacopo da Empoli or simply L'Empoli, stands as a significant figure in the transition of Italian art from the late Mannerist period to the early Baroque. Born in Florence on April 30, 1551, his life and career spanned a period of profound artistic and religious change. His father hailed from the town of Empoli, hence the artist's common moniker, which distinguished him in the bustling Florentine art scene. He passed away in his native Florence on September 30, 1640, leaving behind a rich legacy of works that championed clarity, naturalism, and devotional sincerity.

Early Training and Formative Influences

Jacopo Chimenti's artistic journey began in the workshop of Maso da San Friano, a respected Florentine painter. This apprenticeship provided him with a solid grounding in the prevailing artistic traditions of the city. However, Chimenti's development was significantly shaped by his engagement with the reformist currents that sought to move away from the perceived artificiality and intellectual complexities of High Mannerism.

A pivotal influence on Chimenti was Santi di Tito, a leading proponent of the "Counter-Maniera" movement in Florence. Santi di Tito advocated for a return to the clarity, naturalism, and direct emotional appeal found in the works of earlier Renaissance masters like Andrea del Sarto and Fra Bartolomeo. This reformist spirit, deeply intertwined with the religious directives of the Council of Trent (1545-1563) which called for art that was easily understandable and capable of inspiring piety, resonated strongly with Chimenti. He absorbed these ideals, striving to create compositions that were legible, devout, and grounded in a careful observation of the natural world. While he would have studied the works of High Renaissance giants such as Raphael and Michelangelo, his more immediate stylistic dialogue was with figures like Santi di Tito and the legacy of Andrea del Sarto, whose balanced compositions and gentle naturalism offered an alternative to the elongated forms and complex allegories of artists like Pontormo or Bronzino.

Artistic Style: Clarity, Naturalism, and Devotion

Chimenti's mature style is characterized by its lucidity, unpretentious naturalism, and a restrained emotional depth. His figures are often robust and tangible, rendered with a careful attention to anatomy and expression. Unlike the often-crowded and contorted compositions of some late Mannerist painters, Chimenti favored clear arrangements, where the narrative or devotional subject was communicated directly to the viewer. His color palettes are typically rich but harmonious, and his handling of light and shadow, while not as dramatically stark as Caravaggio's Tenebrism, effectively models form and creates a sense of atmosphere.

He consciously avoided the overly elaborate, the intellectually obscure, and the artificially elegant that had marked much of the Mannerist output. Instead, Chimenti's work embodies a return to "verità e natura" – truth and nature. This commitment is evident in the lifelike portrayal of his figures, the realistic rendering of textures, and the straightforward presentation of his subjects. His approach stood in contrast to the more flamboyant and decorative tendencies that would characterize much of Baroque art elsewhere in Italy, aligning him more with a Florentine tradition of disegno (drawing/design) and a certain classical restraint. Artists like Ludovico Cigoli and Gregorio Pagani were also part of this Florentine reform, each contributing to a renewed sense of naturalism and emotional directness in the city's art.

Religious Works and Altarpieces

A significant portion of Jacopo da Empoli's oeuvre consists of religious paintings, particularly altarpieces, which were in high demand during the Counter-Reformation. These works exemplify his commitment to creating art that was both aesthetically pleasing and spiritually edifying. His religious scenes are imbued with a sense of sincere piety, and the figures often display relatable human emotions.

One of his notable early religious commissions was the tapestry design for the Annunciation (1591) for the church of San Remigio in Florence. His painting Madonna of Succour (1593), now housed in the Pitti Palace, showcases his ability to convey tender maternal care within a sacred context. The Sacrifice of Isaac, a theme he painted in the 1590s (versions exist, including one in the Uffizi Gallery), demonstrates his skill in depicting dramatic narratives with clarity and emotional force, focusing on the human drama within the biblical story.

Another important work is Saint Ivo Reading the Petitions of Widows and Orphans, painted for the Magistrato dei Pupilli and now in the Pitti Palace. This painting was highly praised for its compassionate depiction of the saint and the vulnerable figures around him, showcasing Chimenti's ability to blend social realism with religious sentiment. His Beautification of St. Ignatius further highlights his role in producing imagery that supported the newly prominent religious orders and their saints. The Three Marys at the Tomb is another example of his capacity to render poignant biblical moments with dignity and accessible emotion. His works often adorned churches not just in Florence but also in surrounding Tuscan towns, including Empoli itself, where the Museo della Collegiata di Sant'Andrea holds important examples of his art, such as an early Madonna and St. John (c. 1575).

Contribution to Still Life Painting

Beyond his religious commissions, Jacopo da Empoli made a notable contribution to the development of still life painting in Italy. While the genre was more established in Northern Europe, Chimenti was among the pioneers who helped popularize it in Florence. His still lifes are characterized by their meticulous detail, rich textures, and an appreciation for the humble objects of everyday life.

Works like Pantry with Cask, Game, Meat, and Pottery (1624) or his various Still Life with Game compositions offer a fascinating glimpse into the material culture of 17th-century Tuscany. These paintings depict an array of foodstuffs, kitchen utensils, and hunted game, arranged with a sense of order and an eye for verisimilitude. They are not merely decorative; they celebrate the bounty of nature and the domestic sphere. In this, Chimenti can be seen alongside other early Italian still life painters, though his approach was distinctly Florentine in its careful drawing and composition. He predates the more opulent Baroque still lifes of artists like Giovanna Garzoni but shares with pioneers like Fede Galizia an interest in the faithful representation of objects.

His kitchen scenes often include figures, blurring the line between pure still life and genre painting. These works provide valuable insights into the daily routines and culinary habits of the period, rendered with the same commitment to naturalism that characterized his religious art.

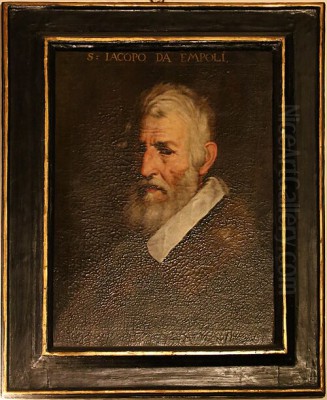

Portraits and Historical Scenes

Jacopo da Empoli was also an accomplished portraitist, though fewer examples of this genre survive or are definitively attributed to him. His portraits, like his other works, tend towards a straightforward and honest representation of the sitter, capturing individual likeness without excessive flattery.

He also undertook historical paintings. A particularly interesting example is Michelangelo Presenting the Model of the Facade of San Lorenzo to Pope Leo X (1619), now in the Casa Buonarroti in Florence. This work is a historical reconstruction, celebrating a key moment in Florentine artistic and papal history, and demonstrates Chimenti's ability to manage complex multi-figure compositions and convey a sense of historical occasion. The depiction of prominent figures like Michelangelo and Pope Leo X (a Medici) required careful research and a dignified presentation.

Technical Skill and Workshop Practice

Chimenti was renowned for his exceptional drawing skills, a foundation of Florentine artistic practice. Numerous preparatory drawings for his paintings survive, attesting to his meticulous working process. These drawings, often in chalk or ink, reveal his careful study of anatomy, drapery, and composition.

An interesting anecdote relates to two of his drawings depicting a young man holding a compass and a plumb line. In 1859, Alexander Crum Brown, a Scottish chemist, reportedly combined these two slightly different drawings using conjugate parallax to demonstrate a stereoscopic (3D) effect. While the drawings were likely not originally intended for such a purpose in the 16th or 17th century, the incident highlights the precision and subtle variations in Chimenti's draughtsmanship that made such an experiment possible.

Like many successful artists of his time, Jacopo da Empoli maintained an active workshop. He trained a number of pupils who went on to have careers of their own. Among his most notable students were Felice Ficherelli, known as "Il Riposo," who developed a distinctive style influenced by Chimenti's naturalism but also incorporating softer, more sensuous elements. Giovanni Battista Vanni was another student who absorbed Chimenti's teachings. The presence of a workshop allowed Chimenti to undertake numerous commissions and disseminate his artistic principles. His brother, Domenico Chimenti, also worked as a painter and may have collaborated with him. There is also speculation about potential early collaborations or workshop connections with figures like Giorgio Vasari, though Chimenti would have been very young, or later with artists such as Alessandro Tiarini, a Bolognese painter who also worked in Florence.

The "L'Empilo" Nickname and Personal Life

Beyond his artistic endeavors, a charming detail about Chimenti's personality is preserved in his nickname "L'Empilo," which translates to "the stewpot" or "the fill-up." This moniker was reportedly given to him due to his fondness for good food and generous portions, suggesting a convivial and perhaps gourmand aspect to his character. Such personal details, though scarce, help to humanize the artist behind the extensive body of work. He remained largely based in Florence throughout his long and productive life, deeply embedded in the city's artistic and social fabric.

Later Career and Enduring Legacy

Jacopo da Empoli remained active well into his old age, continuing to produce significant works. His style, while consistent in its core principles of clarity and naturalism, showed subtle evolutions over his long career. Some scholars note a potential, albeit restrained, influence from the early works of Caravaggio in his handling of light and shadow, particularly in the first decade of the 17th century, though Chimenti never fully embraced Caravaggesque drama. His primary allegiance remained to the Florentine tradition of reform.

His death in 1640 marked the end of a significant era in Florentine painting. He had successfully navigated the transition from late Mannerism, contributing significantly to a reformed style that emphasized directness, piety, and a renewed connection to nature. His influence extended through his students and through the example of his numerous works in churches and collections in Florence and Tuscany.

Jacopo Chimenti da Empoli is remembered as a diligent and highly skilled painter who played a crucial role in the revitalization of Florentine art at the turn of the 17th century. He was a bridge figure, absorbing the lessons of the High Renaissance masters like Andrea del Sarto, reacting against the excesses of Mannerism alongside reformers like Santi di Tito, and paving the way for new artistic directions, all while maintaining a distinctively Florentine character in his art. His commitment to clarity, his sensitive portrayal of human emotion, and his pioneering work in still life ensure his lasting importance in the history of Italian art. His works continue to be studied and admired for their technical mastery and their sincere, unpretentious beauty, offering a window into the artistic and spiritual world of late Renaissance and early Baroque Florence. He stands apart from the more dramatic Baroque styles developing elsewhere, for instance, the dynamism of a Pietro da Cortona (who would later work in Florence), by maintaining a more sober and grounded aesthetic.