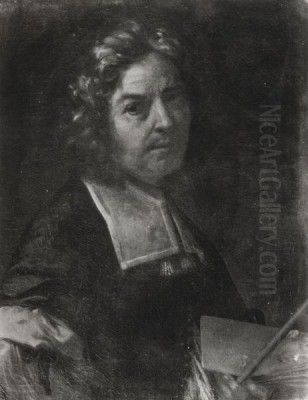

Jacopo Vignali (1592–1664) stands as a significant figure in the landscape of 17th-century Florentine painting. Operating during the vibrant Baroque era, often referred to as the Seicento in Italy, Vignali carved out a distinct artistic identity. His work is characterized by its deep emotional resonance, sophisticated use of color, and a masterful handling of light and shadow, all while remaining rooted in the rich artistic traditions of Florence. Born in Pratovecchio, a small town in the Casentino valley, his destiny was intrinsically linked with Florence, the city where he would train, flourish, and eventually pass away, leaving behind a considerable body of work that continues to be appreciated for its technical skill and expressive power.

Early Life and Formative Influences

Jacopo Vignali's artistic journey began in earnest when he moved to Florence and entered the bustling workshop of Matteo Rosselli (1578–1650). Rosselli was one of the leading painters in Florence at the time, known for his prolific output, his adherence to the Florentine tradition of disegno (design or drawing), and his ability to manage large-scale commissions. Under Rosselli's tutelage, Vignali would have received a thorough grounding in the fundamentals of drawing, composition, and painting techniques. Rosselli's style, while rooted in the late Renaissance, was open to the newer currents of the early Baroque, emphasizing clarity, narrative force, and a certain sobriety.

During these formative years, Vignali was not only shaped by his master but also by the broader artistic environment of Florence. The influence of Ludovico Cardi, known as Cigoli (1559–1613), was particularly potent. Cigoli was a pivotal figure in the transition from late Mannerism to the early Baroque in Florence. He championed a return to naturalism, a more expressive use of color, and a heightened sense of emotional drama in religious painting, moving away from the more artificial and stylized conventions of late Mannerism. Artists like Gregorio Pagani (1558-1605) and Jacopo da Empoli (c. 1551–1640) were also part of this reform movement, advocating for clarity and directness. Vignali absorbed these trends, and his early works, such as the "Assumption of the Virgin" and "Love of Country" (also cited as "Patriotism" or "Amor di Patria"), likely reflect this blend of Rosselli's structured approach and Cigoli's more emotive and coloristic tendencies.

The artistic atmosphere in Florence was rich, with figures like Cristofano Allori (1577–1621), famous for his "Judith with the Head of Holofernes," also making significant contributions. While Vignali was developing his skills, the legacy of earlier masters like Andrea del Sarto (1486-1530) and Fra Bartolomeo (1472-1517) still resonated, particularly their emphasis on balanced compositions and graceful figures.

Entry into the Accademia del Disegno and Early Career

A significant milestone in Vignali's early career was his admission into the prestigious Accademia del Disegno in 1616. Founded by Giorgio Vasari under the patronage of Cosimo I de' Medici, the Accademia was the first formal art academy in Europe and played a crucial role in shaping artistic practice and theory in Florence. Membership was a mark of professional recognition. Vignali's involvement deepened, and by 1622, he was recognized as an academician, a testament to his growing skill and reputation within the Florentine artistic community.

His early career saw him undertaking various commissions, primarily for churches and religious confraternities in Florence and the surrounding Tuscan region. These works allowed him to refine his style, gradually moving towards a more personal artistic expression. While portraiture was part of his output, his primary focus became narrative compositions, predominantly religious scenes. This was a period where the Counter-Reformation's influence was still strong, demanding art that was clear, doctrinally sound, and capable of inspiring piety and devotion in the faithful. Vignali's ability to convey sincere emotion and create visually engaging narratives made him well-suited for such commissions.

His paintings from this period began to show a more pronounced use of chiaroscuro – the dramatic interplay of light and dark – which added depth and intensity to his scenes. His palette became richer and more varied, moving beyond the somewhat more restrained colors of his earliest training. The figures in his compositions started to exhibit more dynamic poses and expressive gestures, contributing to the overall theatricality and emotional impact of his work, hallmarks of the burgeoning Baroque style.

Artistic Development and Mature Style

As Jacopo Vignali matured as an artist, his style evolved, distinguishing itself more clearly from that of his teacher, Matteo Rosselli. While the foundational principles of Florentine disegno remained, Vignali embraced a more painterly approach, with a richer application of paint and a more nuanced handling of color and light. His compositions often feature a dynamic energy, with figures interacting in complex yet coherent spatial arrangements.

A key characteristic of Vignali's mature style is his ability to imbue his subjects with profound psychological depth and emotional intensity. Whether depicting scenes of martyrdom, ecstasy, or quiet devotion, his figures convey a palpable sense of human feeling. This emotional resonance was achieved through careful attention to facial expressions, gestures, and the overall atmosphere of the painting. His use of warm, often earthy tones, punctuated by vibrant highlights, contributed to the dramatic and affective quality of his work.

His brushwork became more confident and expressive, allowing for a greater sense of texture and movement. The drapery in his paintings is often rendered with a sense of weight and volume, its folds catching the light in a way that enhances the three-dimensionality of the figures. This period saw him tackle increasingly ambitious projects, including large altarpieces and fresco cycles, which demanded not only technical skill but also a sophisticated understanding of narrative and composition on a grand scale. Artists like Giovanni da San Giovanni (1592-1636), a contemporary known for his lively frescoes, were also active in Florence, contributing to a vibrant scene for large-scale decorative projects.

Major Commissions and Illustrious Patrons

Throughout his career, Jacopo Vignali received numerous important commissions, a testament to his esteemed position in the Florentine art world. Among his most notable patrons was the powerful Medici family, who had long been the preeminent patrons of the arts in Florence. For the Medici, Vignali executed several significant works, including frescoes. One such important commission mentioned is the fresco of the "Coronation of St. Peter." Working for the Medici not only provided financial stability but also enhanced an artist's prestige considerably.

Beyond the Medici, Vignali worked extensively for various churches and religious orders in Florence and Tuscany. These commissions often involved creating large altarpieces, paintings for side chapels, and decorative cycles. His religious works were praised for their devotional sincerity and their ability to communicate complex theological themes in an accessible and moving manner. Works like "Archangel Michael" and "The Judgment of Solomon" are cited as examples of his significant output in this genre. "The Judgment of Solomon," a popular subject in Baroque art, would have allowed Vignali to showcase his skill in depicting a dramatic narrative, contrasting emotions, and a complex figural group.

The demand for religious art was high, and Vignali's workshop was likely a busy one, possibly employing assistants to help with larger commissions, a common practice at the time. His reputation for professionalism and piety, coupled with his artistic skill, made him a sought-after painter for patrons seeking works that were both aesthetically pleasing and spiritually edifying. The Florentine artistic scene also included painters like Francesco Furini (1603-1646), known for his soft, sfumato-laden style, and Cecco Bravo (1601-1661), whose work was more idiosyncratic and imaginative, providing a diverse context for Vignali's more classically inclined Baroque style.

Notable Works and Stylistic Hallmarks

Several specific works highlight Jacopo Vignali's artistic prowess and stylistic characteristics. Among those frequently mentioned are studies of heads, such as "Tête de vieillard accroupi" (Head of a Crouching Old Man) and "Tête de vieillard accoudé" (Head of a Leaning Old Man). These studies, likely executed in oil or chalk, demonstrate his keen observational skills and his ability to capture character and emotion with great sensitivity. Such works often reveal an artist's technical mastery in rendering flesh tones, the texture of hair and beards, and the subtle play of light on form.

A particular technical feature associated with Vignali, and indeed with the meticulous Florentine tradition, is the "filamentare" or "hair-line" technique, especially noted in the rendering of beards. This involved painting individual strands of hair with fine, precise lines, creating a highly detailed and almost tangible effect. This precision, while perhaps most famously associated with his student Carlo Dolci, was a characteristic Vignali himself employed, showcasing the Florentine emphasis on careful craftsmanship.

His larger narrative paintings, such as the aforementioned "Coronation of St. Peter," "Archangel Michael," and "Judgment of Solomon," would have displayed his ability to manage complex compositions, create dynamic figural arrangements, and convey dramatic action. In these works, one would expect to see his characteristic use of rich, warm colors, strong contrasts of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) to model forms and create atmosphere, and figures imbued with expressive gestures and emotional depth. The "St. Peter" fresco, for instance, would likely have been a grand, uplifting scene, suitable for its prominent placement and powerful patrons.

The Art of Tapestry Design: The Four Seasons

A fascinating aspect of Jacopo Vignali's oeuvre is his work as a designer of tapestry cartoons. In the 1640s, he was commissioned to create cartoons for a series of tapestries depicting "The Four Seasons." These tapestries were intended for the Duke's winter rooms, indicating a prestigious commission. Tapestry design required a specific set of skills, as the artist had to create a full-scale painted model (the cartoon) that weavers would then translate into textile. The designs needed to be bold, clear, and suitable for the medium of tapestry, which often favored broad effects over minute detail, though Florentine tapestries were known for their refinement.

For this "Four Seasons" series, Vignali reportedly drew inspiration from different sources. For the allegories of Spring and Summer, he is said to have referenced works by Francesco Salviati (1510–1563), a prominent Mannerist painter who had also worked extensively in Florence and Rome and was known for his elegant and complex designs. Salviati himself had designed tapestries, so looking to his precedent was logical.

However, for Autumn and Winter, Vignali took a different approach, creating scenes of contemporary daily life. These depictions included activities of the nobility and scenes within castles, offering a glimpse into the aristocratic lifestyle of the period. This choice reflects a broader Baroque interest in genre scenes and the depiction of everyday reality, even within allegorical frameworks. The challenge of creating these cartoons would have been significant, particularly given the scale and the need to coordinate with the tapestry weavers. Records indicate that he submitted the cartoons for "The Four Seasons" in 1643 and also completed work on the border for the "Winter" tapestry in the same year. The fact that the weaving of a second edition of these tapestries began in 1643 while the first was still in progress suggests the popularity of the designs and the pressures Vignali might have faced in delivering these complex works.

Vignali as a Teacher: The Case of Carlo Dolci

Jacopo Vignali was not only a prolific painter but also a respected teacher. His most famous pupil was Carlo Dolci (1616–1686), who became one of the leading figures of Florentine Baroque painting, renowned for his highly polished, intensely devotional images, often of single figures like Madonnas or saints, rendered with an almost enamel-like smoothness and meticulous detail.

Dolci entered Vignali's studio at a young age and absorbed much from his master. Vignali is credited with teaching Dolci the "emotionalized" approach to painting, emphasizing the conveyance of sincere piety and tender sentiment. This focus on affective devotion became a hallmark of Dolci's own work. Furthermore, the meticulous attention to detail, including the "filamentare" technique for rendering hair, which was characteristic of Vignali's practice, was certainly passed on to Dolci, who took this precision to an even greater extreme.

While Dolci developed his own distinct style, characterized by a heightened sweetness and an almost porcelain-like finish, the foundations laid during his apprenticeship with Vignali were crucial. The master-pupil relationship was a cornerstone of artistic training in this period, and Vignali's role in nurturing Dolci's talent underscores his importance within the Florentine artistic lineage. It's important to note that while some sources might suggest Vignali inherited Dolci's tradition, the historical record clearly indicates Vignali was the teacher and Dolci the student, with Dolci building upon the meticulous and emotive qualities he learned from Vignali.

Contemporaries and the Florentine Milieu

Jacopo Vignali operated within a vibrant and competitive artistic environment in 17th-century Florence. While Rome was the undisputed center of the Baroque, Florence maintained its own distinct artistic identity, characterized by a continued reverence for disegno, a certain restraint compared to the more exuberant Roman Baroque, and a preference for clarity and emotional sincerity.

Besides his teacher Matteo Rosselli and his student Carlo Dolci, Vignali's contemporaries included a diverse group of artists. Lorenzo Lippi (1606–1665), also a poet, was known for his naturalistic style and his adherence to Florentine traditions. Baldassare Franceschini, known as Il Volterrano (1611–1690), was a highly successful painter, particularly renowned for his illusionistic ceiling frescoes. Justus Sustermans (1597–1681), a Flemish painter who became the court portraitist to the Medici, brought a Northern European sensibility to Florentine portraiture.

These artists, along with others like Felice Ficherelli (1605-1660), often competed for the same commissions and influenced each other's work, contributing to the rich tapestry of Florentine Seicento art. Vignali's ability to secure consistent patronage and maintain a successful workshop amidst such talent speaks to the quality and appeal of his art. He was an active member of the Accademia del Disegno, which served as a hub for artists, facilitating exchanges of ideas and fostering a sense of community.

Later Years, Death, and Legacy

Jacopo Vignali remained a dedicated and productive artist throughout his life. He was known for his devout character and his unwavering professionalism. Unlike some of his contemporaries who might have traveled to Rome or other artistic centers to broaden their horizons, Vignali seems to have been content to base his entire career in Florence. This deep connection to his adopted city is reflected in the numerous works he created for its churches, palaces, and private collections.

He continued to paint until his death in Florence in 1664 at the age of 72. His passing was marked by a funeral organized by the members of the Accademia del Disegno, a final tribute from his peers that underscored the respect he commanded within the Florentine artistic community.

Vignali's legacy is multifaceted. He contributed significantly to the corpus of Florentine Baroque art, creating works that combined technical skill with genuine emotional depth. His paintings served as important devotional aids and adorned many of Florence's most significant religious and civic spaces. As a teacher, he played a crucial role in shaping the next generation of artists, most notably Carlo Dolci, thereby ensuring the continuation of certain Florentine artistic traditions. His work in tapestry design also highlights his versatility.

Art Historical Evaluation and Enduring Influence

In the broader sweep of Italian Baroque art, Jacopo Vignali is recognized as a key representative of the Florentine school. His style, while participating in the general trends of the Baroque such as dramatic lighting and emotional intensity, retained a distinct Florentine character, marked by an emphasis on clear drawing, balanced composition, and a certain lyrical grace. He successfully navigated the demands of patrons, producing a large body of work that was both popular in its time and has endured in its appeal.

His influence can be seen in the work of his students and followers. The meticulous technique and devotional sentiment he fostered, particularly evident in the art of Carlo Dolci, had a lasting impact on religious painting in Florence. While perhaps not as revolutionary as some of his Roman contemporaries like Caravaggio or Bernini, Vignali's contribution was vital to the continued vibrancy of artistic production in Florence during the Seicento.

Today, his paintings can be found in numerous churches and museums in Florence and Tuscany, as well as in collections elsewhere. Art historians continue to study his work, appreciating his skillful synthesis of tradition and innovation, his expressive power, and his role in the rich artistic fabric of 17th-century Florence. He stands as a testament to the enduring strength of the Florentine artistic heritage, adapting its principles to the expressive demands of the Baroque age with sensitivity and skill. His dedication to his craft and his city ensured him a lasting place in the annals of Italian art history.