The annals of art history are replete with celebrated masters whose lives and works are meticulously documented. Yet, for every Turner or Constable, there exist countless other artists whose contributions, though perhaps more modest or localized, form an integral part of the rich tapestry of their era. James Lawson Stewart, a figure ostensibly active in the 19th century, presents a fascinating case study in the challenges of reconstructing an artistic identity from fragmented and sometimes contradictory records. This exploration seeks to piece together the available information, place it within the broader context of Victorian art, and acknowledge the ambiguities that often accompany the study of less globally renowned painters.

The Biographical Conundrum: Pinpointing James Lawson Stewart

One of the immediate challenges in discussing James Lawson Stewart is a significant discrepancy in the biographical data. The primary timeframe provided for our subject is 1809-1883. However, research also uncovers references to a painter named James Lawson Stewart with a birth year of 1841. This chronological divergence is crucial, as it potentially points to two distinct individuals or a significant error in historical records. For the purpose of this discussion, we will primarily focus on the 1809-1883 timeframe, while also acknowledging the information attributed to the later Stewart, as it has become intertwined with the name.

If we accept the 1809-1883 dates, James Lawson Stewart would have been a contemporary of some of the most transformative figures in British art. His life would have spanned the late Georgian period, the entirety of William IV's reign, and the majority of Queen Victoria's long rule. This era witnessed the towering achievements of J.M.W. Turner and John Constable, the rise of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood with figures like Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, and William Holman Hunt, and the flourishing of a vibrant market for genre scenes and landscapes by artists such as William Powell Frith and Myles Birket Foster. The artistic landscape was diverse, encompassing grand history painting, intimate domestic scenes, and an increasing appreciation for the natural and urban environment.

Artistic Profession and Stylistic Leanings

The available information consistently identifies James Lawson Stewart (associated with the 1809-1883 dates) as a painter. His chosen medium appears to have been predominantly watercolour, a technique that enjoyed immense popularity in Britain throughout the 19th century. The Royal Watercolour Society and the New Society of Painters in Water Colours (later the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours) provided important platforms for artists working in this medium. Watercolour was lauded for its portability, immediacy, and capacity to capture subtle atmospheric effects, making it ideal for landscape, architectural views, and topographical illustration.

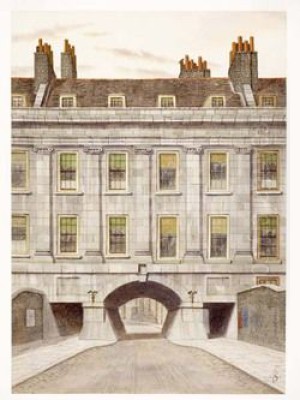

Stewart’s subject matter seems to have centered on London's street scenes and architecture. This focus aligns with a broader Victorian interest in documenting the rapidly changing urban environment. London, as the heart of a global empire and a hub of industrial and commercial activity, was undergoing unprecedented transformation. Artists sought to capture its bustling energy, its historic landmarks, and the everyday life of its inhabitants. Painters like Samuel Prout and David Roberts had earlier established a strong tradition of architectural and topographical watercolour, and Stewart’s work appears to follow in this vein, offering visual records of the city's fabric.

Representative Works: A Glimpse into Stewart's London

A key work attributed to James Lawson Stewart (1809-1883) is a watercolour depicting "New Princes Street, Lambeth." This piece is significant as it exemplifies his engagement with London's topography. Lambeth, situated on the south bank of the Thames, was an area rich in history and undergoing considerable development during the 19th century. A watercolour of New Princes Street would likely have captured the architectural character of the thoroughfare, perhaps including details of buildings, street life, and the prevailing atmosphere of that particular locale. Such works serve not only as artistic expressions but also as valuable historical documents, preserving views of streets and structures that may have since been altered or demolished. The choice of Lambeth is interesting; while areas like Westminster or the City of London were common subjects, Lambeth offered its own distinct character, from the grandeur of Lambeth Palace to more modest residential and commercial streets.

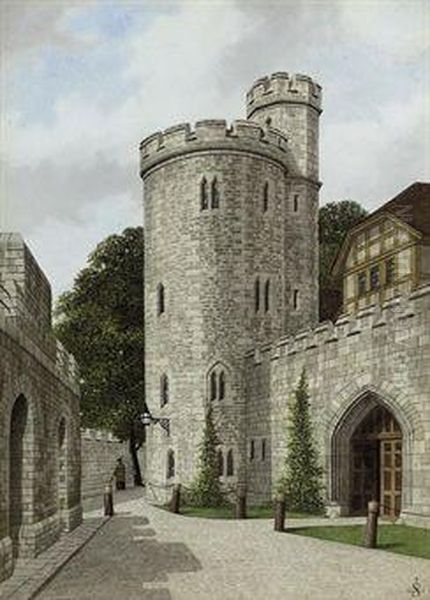

Another work sometimes associated with a James Lawson Stewart is "Brougham Castle, Circa: 1890." This attribution presents a chronological issue if we adhere strictly to the 1809-1883 lifespan, as the "circa 1890" date falls after his supposed death. This could indicate several possibilities: the work might be by the James Lawson Stewart born in 1841; the date could be an estimate for the scene depicted rather than the execution of the artwork; or it could be a posthumous print or a misattribution. Brougham Castle, a picturesque ruin in Cumbria, was a popular subject for artists drawn to the Romantic and historical associations of such sites, much like their predecessors, including Thomas Girtin and J.M.W. Turner, who frequently depicted castles and abbeys. If Stewart did paint Brougham Castle, it would suggest an interest extending beyond urban London to the historical landscapes of northern England.

The mention of Stewart potentially creating illustrations for the works of Charles Dickens is also noteworthy. Dickens was a literary giant of the Victorian era, and his novels were often published with memorable illustrations by artists such as Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"), George Cruikshank, and later, Luke Fildes. If Stewart contributed to this tradition, his work would have reached a wide audience and required a keen ability to translate Dickens's vivid characters and settings into visual form. This would also align with his skill in depicting urban scenes, as many of Dickens's narratives are deeply rooted in the London environment.

The Question of Artistic Education and Affiliations

Regrettably, specific details regarding James Lawson Stewart's formal artistic education or his master-student relationships are scarce for the 1809-1883 period. In the 19th century, aspiring artists often sought training at the Royal Academy Schools in London, or under the tutelage of established painters. Provincial art schools also began to emerge. Without concrete evidence, we can only speculate that Stewart, like many of his contemporaries, may have honed his skills through a combination of formal instruction, private study, and the practical experience of sketching and painting from life.

Similarly, there is little direct information about his participation in major art exhibitions or his membership in artistic societies. Exhibiting at venues like the Royal Academy, the British Institution, or the watercolour societies was crucial for an artist's visibility and career progression. Interaction with fellow artists within these circles was also common, fostering stylistic exchange and professional camaraderie. The absence of such records for Stewart (1809-1883) might suggest a more private practice, a focus on commissions, or perhaps that his exhibition history is yet to be fully uncovered by researchers. Artists like John Sell Cotman, for instance, achieved significant artistic merit but sometimes struggled for wider recognition during their lifetimes compared to more commercially savvy contemporaries.

Anecdotes and Character: The Other James Lawson Stewart?

The information stream becomes particularly complex when considering anecdotal details, as these seem more closely linked to the James Lawson Stewart purportedly born in 1841. This individual is described as having a "solitary character," possibly due to a deep dedication to his work and being older than his immediate peers. This description paints a picture of an introspective and focused individual.

Furthermore, this later Stewart is associated with a "dual mission in medicine and missionary work," making him a "pioneer." There's a tantalizing reference to his "Africa story" not being successfully recorded by students. This suggests a life of considerable adventure and purpose beyond the realm of art, or perhaps an artist who used his skills in the service of these other callings. The combination of medical, missionary, and artistic pursuits was not unheard of, particularly in the context of colonial expansion and exploration, where individuals often possessed multiple skill sets. For example, explorers and naturalists often had considerable drawing skills to document their findings.

An intriguing, if somewhat unsettling, anecdote attributed to this Stewart involves an "altercation with a gentleman's servant," resulting in serious injury to the young man. This incident, if true, reveals a more volatile aspect to his personality, contrasting with the image of a dedicated, solitary worker or a benevolent missionary. Such stories, while adding color, also highlight the difficulty of forming a balanced view of a historical figure from isolated fragments of information. It's crucial to reiterate that these anecdotes are linked to the 1841 Stewart and may not pertain to the painter active between 1809 and 1883.

The Broader Artistic Context of Victorian Britain

To better understand any artist from this period, including James Lawson Stewart, it's essential to consider the artistic environment in which they operated. The 19th century was a time of immense artistic production and diversification in Britain. The Royal Academy of Arts, while a dominant institution, faced challenges from emerging groups and changing tastes. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, founded in 1848 by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, advocated for a return to the detail, intense color, and complex compositions of Quattrocento Italian art. Their influence was profound, even on artists not directly affiliated with the group.

Landscape painting continued to be a major genre, evolving from the Romantic sublimity of Turner to the detailed naturalism favored by many mid-Victorian painters. Artists like Benjamin Williams Leader or George Vicat Cole produced popular and highly finished landscapes. The rise of the middle class as art patrons also fueled demand for genre scenes depicting everyday life, historical narratives, and sentimental subjects, as seen in the works of painters like Thomas Faed or Frederick Goodall.

The interest in architectural and topographical art, Stewart's apparent specialty, remained strong. The Gothic Revival, championed by architects like Augustus Pugin (who himself was a skilled watercolourist) and writers like John Ruskin, fostered an appreciation for medieval architecture and detailed rendering. Ruskin, a hugely influential art critic, also emphasized truth to nature and meticulous observation, which resonated with many artists, including the Pre-Raphaelites and landscape painters. Stewart's focus on London's architecture would have found a receptive audience, both for its aesthetic appeal and its documentary value in an era of rapid urban change. One might imagine his work sharing wall space in exhibitions with that of artists like Samuel Read, known for his interior views of cathedrals, or perhaps even the cityscapes of a later artist like John Atkinson Grimshaw, who captured the mood of Victorian cities by gaslight.

The Challenge of Historical Obscurity

The difficulties encountered in assembling a comprehensive biography and oeuvre for James Lawson Stewart (1809-1883) are not uncommon in art history. Many talented artists, for various reasons, do not achieve lasting fame or leave behind extensive, easily accessible records. Their works may be in private collections, their exhibition history sporadic, or their personal papers lost to time. Sometimes, artists focused on regional markets or specialized in areas like illustration or topographical work that, while valued, did not always confer the same level of "high art" status as, for example, large-scale oil paintings exhibited at the Royal Academy.

The conflicting birth dates further complicate the picture, raising the possibility that the records of two or more artists with the same name have become conflated over time. This is a common pitfall in historical research, requiring careful sifting of evidence and a cautious approach to attribution. The art market also plays a role; works by lesser-known artists may circulate with minimal provenance, making it difficult to trace their history or firmly attribute them.

Conclusion: An Artist in the Margins of History

James Lawson Stewart, particularly the figure associated with the 1809-1883 lifespan, emerges as a painter of London's urban landscape, working primarily in watercolour. His depiction of "New Princes Street, Lambeth" suggests a commitment to capturing the specific character of the Victorian metropolis. The potential connection to Dickens's illustrators and the enigmatic "Brougham Castle" hint at a broader scope, though these aspects remain less clearly defined.

The lack of detailed information regarding his training, exhibition history, and personal life means he remains a somewhat elusive figure. The contrasting information associated with a James Lawson Stewart born in 1841, with his purported missionary work and distinct personality traits, adds another layer of complexity, underscoring the need for further research to clarify whether these are indeed separate individuals.

Despite the ambiguities, the work attributed to James Lawson Stewart (1809-1883) offers a valuable, if modest, window into the visual culture of 19th-century Britain. His watercolours of London contribute to the rich tradition of topographical art that documented a city in constant flux. Like many artists who may not have achieved the fame of a Landseer or a Leighton, Stewart played a part in the artistic ecosystem of his time. Further research in local archives, exhibition catalogues, and genealogical records might yet shed more light on this intriguing but partially obscured Victorian painter, allowing for a fuller appreciation of his place within the diverse and ever-fascinating world of 19th-century British art. His story is a reminder that art history is an ongoing process of discovery, often involving piecing together narratives from the faintest of traces.