The Dutch Golden Age, spanning roughly the 17th century, was a period of extraordinary artistic efflorescence in the Netherlands. Amidst a galaxy of celebrated painters, Jan Jansz. van de Velde III carved out a distinct niche as a refined and thoughtful painter of still lifes. Born into a family already distinguished in the arts, he navigated the bustling art scenes of Haarlem and Amsterdam, contributing significantly to the development of the "monochrome banketje" or monochrome banquet piece, a subgenre that celebrated subtlety, texture, and the quiet beauty of everyday objects.

An Artistic Lineage: The Van de Velde Family

Jan Jansz. van de Velde III, often referred to simply as Jan van de Velde III, was born in Haarlem around 1619 or 1620. He was not the first in his family to pursue an artistic career; indeed, he hailed from a veritable dynasty of artists. His grandfather, Jan van de Velde I (circa 1568–1623), was a renowned calligrapher and schoolmaster from Antwerp who later moved to Rotterdam. His elegant script and influential writing manuals set a high bar for craftsmanship within the family.

The artist's father was Jan van de Velde II (circa 1593–1641), a highly prolific and versatile engraver and print publisher. Jan van de Velde II was celebrated for his landscapes, genre scenes, and portraits, producing hundreds of prints that were widely circulated and admired. He was a pupil of Jacob Matham in Haarlem and was known for his innovative approaches to landscape etching, often capturing atmospheric effects with remarkable skill. It is important to note that some of the characteristics mentioned in preliminary research, such as a vast output of prints, concerns about paper shortages, or themes like the "Dance of Death" or overtly ironic symbolism in graphic works, are more directly attributable to Jan van de Velde II, the engraver, rather than his son, the still-life painter.

Furthermore, Jan Jansz. van de Velde III's great-uncle (his father's paternal uncle or cousin, depending on the exact family tree interpretation, though often cited as Esaias van de Velde's cousin) was the highly influential landscape painter Esaias van de Velde (circa 1587–1630). Esaias was a pioneer of realistic landscape painting in the Netherlands, moving away from the more artificial, mannerist styles of his predecessors. His work had a profound impact on subsequent generations of Dutch landscape artists, including figures like Jan van Goyen and Salomon van Ruysdael. Growing up in such an environment, surrounded by discussions of art, technique, and the business of art, undoubtedly shaped young Jan III's path.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Haarlem

Haarlem in the early 17th century was a vibrant center for painting, particularly renowned for its still-life specialists. It was in this stimulating milieu that Jan Jansz. van de Velde III likely received his initial artistic training. While direct documentation of his apprenticeship is scarce, his stylistic affinities strongly suggest a close connection to the leading still-life painters of Haarlem, most notably Willem Claesz. Heda (1594–1680) and, by extension, Pieter Claesz. (1597/98–1660).

Heda and Claesz. were the principal exponents of the "monochrome banketje." These were deceptively simple compositions, typically depicting the remnants of a meal – a half-empty roemer (a type of wine glass), a pewter plate with a partially eaten pie, a bread roll, a knife, perhaps some nuts or a lemon. What set these works apart was their restricted palette, dominated by subtle gradations of grey, brown, and green, and their extraordinary attention to the rendering of texture and light. The gleam of light on a glass, the dull sheen of pewter, the crumbly texture of bread – all were captured with breathtaking verisimilitude.

Jan van de Velde III's works clearly demonstrate his absorption of these principles. He adopted the limited color range, the careful arrangement of objects, and the meticulous rendering of surfaces that characterized the Haarlem school. His early works, dating from the late 1630s, already show a remarkable command of these techniques.

The Characteristics of Van de Velde III's Still Lifes

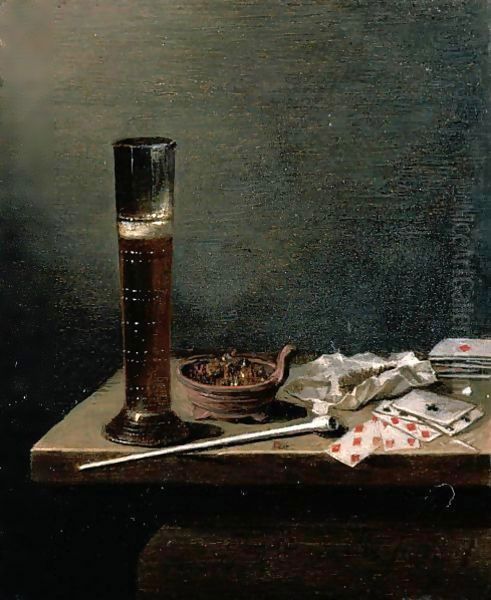

Jan Jansz. van de Velde III's oeuvre primarily consists of still lifes, often modest in scale but rich in detail and atmosphere. His paintings typically feature a selection of common household items, arranged with an eye for balance and harmony.

Subject Matter: His preferred subjects included glassware, such as tall-stemmed Berkemeyer glasses, roemers, and flute glasses, often depicted with wine. Pewter and silver objects, like plates, pitchers, and candlesticks, also feature prominently. Food items are common: bread rolls, lemons (often peeled, allowing the artist to showcase his skill in rendering the pith and glistening fruit), nuts, olives, and occasionally a piece of ham or a pie. Smoking paraphernalia, such as clay pipes and tobacco, also appear, reflecting a common pastime of the era.

Composition: Van de Velde III often employed diagonal compositions, leading the viewer's eye into the painting. Objects are typically arranged on a wooden table, sometimes partially covered with a white or dark cloth. There is a sense of informal elegance; the arrangements appear casual, as if the meal has just been interrupted, yet they are meticulously planned to create a harmonious whole. He often used a relatively high viewpoint in his earlier works, which became lower in his later pieces, aligning more with the mature style of Heda.

Light and Texture: A hallmark of his work is the masterful depiction of light and texture. He excelled at capturing the way light reflects off different surfaces – the transparency of glass, the cool gleam of metal, the rough texture of a bread crust, the soft folds of a napkin. His use of subtle highlights and shadows creates a convincing sense of volume and space.

Color Palette: True to the "monochrome banketje" tradition, Van de Velde III favored a restrained palette. Shades of grey, brown, ocher, and green predominate, creating a subtle, harmonious effect. Accents of color, such as the yellow of a lemon or the red of wine, are used sparingly but effectively. This limited palette allowed him to focus on tonal values and the interplay of light and shadow.

Symbolism and Vanitas: Like many Dutch still lifes of the period, Van de Velde III's paintings often carry symbolic meanings, particularly related to the theme of vanitas – the transience of life and the futility of earthly pleasures. Objects like snuffed-out candles, watches, skulls (though less common in his work compared to some contemporaries), and half-eaten food can all allude to the passage of time and the inevitability of death. The peeled lemon, a luxury item, could symbolize the deceptive allure of worldly pleasures, beautiful on the outside but sour within. Even the act of depicting everyday objects could serve as a reminder to appreciate the simple things in life and to reflect on deeper spiritual matters. However, his symbolism is generally more understated than that of artists like David Bailly or Harmen Steenwijck, who specialized in more overt vanitas compositions.

Notable Works and Stylistic Development

Several works exemplify Jan Jansz. van de Velde III's skill and artistic vision. An early piece, "Still Life with Wine Glass, Grapes, and Walnuts" (1639), already showcases his command of texture and light, with the delicate rendering of the glassware and the realistic depiction of the fruit and nuts.

A work like "Still Life with a Tall Beer Glass, Roemer, Nuts, and a Pipe on a Table" (circa 1640s) is characteristic of his mature style. The composition is balanced, the objects rendered with precision. The tall, slender beer glass (a passglas) provides a vertical accent, while the roemer, with its prunted stem, catches the light beautifully. The scattered nuts and the clay pipe add to the informal atmosphere.

Another example, "Still Life with Roemer, Flute Glass, and Earthenware Jug" (1651), demonstrates his continued refinement. The interplay of different materials – glass, ceramic, pewter – is handled with great sensitivity. The light filtering from an unseen source creates subtle reflections and shadows, imbuing the scene with a quiet, contemplative mood.

The work sometimes cited as "The Scavenger" (1645) is less typical of his known oeuvre if it depicts a figure, as his fame rests almost entirely on his still lifes. If it is a still life with an unusual title, it might refer to a collection of discarded or humble items, perhaps with a moralizing intent. However, his most recognized and influential works are firmly within the "breakfast" or "banquet piece" tradition.

Throughout his career, there is a discernible development in his style. While always adhering to the principles of the monochrome still life, his later works sometimes show a slightly richer palette and more complex arrangements, perhaps reflecting the broader trends in Dutch still-life painting, which saw the rise of more opulent pronkstilleven (ostentatious still lifes) by artists like Abraham van Beyeren and Willem Kalf. However, Van de Velde III largely remained true to the more restrained aesthetic of his Haarlem origins.

Life in Amsterdam and Enkhuizen

While Haarlem was his birthplace and formative environment, Jan Jansz. van de Velde III also spent significant periods in other Dutch cities. Records indicate he married Dieuwertje Heeringhs in Amsterdam on April 21, 1643. Amsterdam was by then the preeminent commercial and artistic hub of the Netherlands, home to artists like Rembrandt van Rijn and a thriving art market. It's plausible that Van de Velde III sought to capitalize on the opportunities available in the larger city. He and his wife had children, continuing the Van de Velde lineage.

Later in his life, he is documented in Enkhuizen, a port town on the Zuiderzee. According to the Netherlands Institute for Art History (RKD), Jan Jansz. van de Velde III died in Enkhuizen and was buried there on July 10, 1662. The reasons for his move to Enkhuizen are not entirely clear, but it was not uncommon for artists to relocate in search of patronage or different living conditions. Some sources mention economic difficulties in his life, a common plight for many artists of the era, even those with considerable talent. Relying on friends or patrons for support was a reality for many.

Contemporaries and the Wider Artistic Milieu

Jan Jansz. van de Velde III operated within a rich and competitive artistic landscape. In Haarlem, besides his primary influences Willem Claesz. Heda and Pieter Claesz., other still-life painters like Floris van Dyck and Nicolaes Gillis had earlier established the "ontbijtje" (breakfast piece) tradition. The great portraitist Frans Hals was also a dominant figure in Haarlem, shaping the city's artistic identity.

In the broader Dutch context, still-life painting was flourishing with diverse specializations. Clara Peeters was an early pioneer of still life, particularly known for her detailed depictions of food and tableware. Later in the century, artists like Abraham van Beyeren and Willem Kalf developed the pronkstilleven, characterized by lavish displays of silverware, exotic fruits, and expensive textiles. Jan Davidsz. de Heem was another master of opulent still lifes, often incorporating flowers and fruit. Flower painting itself was a major genre, with artists like Rachel Ruysch and Jan van Huysum achieving international fame.

Beyond still life, the Dutch Golden Age saw masters in every genre. Rembrandt van Rijn dominated history painting and portraiture in Amsterdam. Johannes Vermeer in Delft created serene and enigmatic genre scenes. Landscape painters like Jacob van Ruisdael (also from Haarlem) and Meindert Hobbema captured the Dutch countryside with unparalleled sensitivity. Genre painters such as Jan Steen, Adriaen van Ostade, and Gerard Dou depicted scenes of everyday life, from boisterous peasant gatherings to quiet domestic interiors. This vibrant artistic ecosystem provided both competition and inspiration for artists like Van de Velde III.

While there is no specific documented record of close personal friendships or collaborations between Van de Velde III and many of these figures beyond the clear stylistic debt to Heda and Claesz., artists in Dutch cities often belonged to the same Guild of Saint Luke, which regulated the art trade and provided a framework for professional interaction. His works, appearing in collections and inventories, suggest he was part of this active art market. The depiction of Chinese porcelain, which began to appear more frequently in Dutch still lifes, indicates an awareness of global trade and the luxury goods available to the increasingly wealthy Dutch populace, items also depicted by contemporaries like Willem Kalf.

Reassessment, Misattributions, and Legacy

The legacy of Jan Jansz. van de Velde III is primarily as a skilled and sensitive practitioner of the monochrome still life. He may not have achieved the same level of fame as Rembrandt or Vermeer, or even the most celebrated still-life specialists like Kalf or De Heem, but his contribution to the genre is undeniable. His works are appreciated for their technical finesse, their subtle beauty, and their quiet, contemplative mood.

It is important to distinguish his career from that of his father, Jan van de Velde II. The latter, as a prolific engraver, had a much wider dissemination of his work through prints. Any discussion of being an "underestimated printmaker" or of "copying Baroque artists" in print form would more accurately apply to Jan van de Velde II. Jan Jansz. van de Velde III was, first and foremost, a painter. His "humorous drawings" or works with overt "death dance" themes, if they exist, are not what define his primary artistic identity, which is rooted in painted still lifes. These thematic elements are far more characteristic of the graphic art of his father or the calligraphic moralizing of his grandfather.

His paintings can be found in numerous museums and private collections worldwide, including the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. They continue to be admired for their quintessential Dutch Golden Age qualities: meticulous observation, masterful technique, and an ability to find beauty and meaning in the everyday.

While perhaps not an innovator on the scale of Heda or Claesz., Jan Jansz. van de Velde III skillfully elaborated upon their achievements, creating works of enduring appeal. He represents a significant strand in the rich tapestry of Dutch Golden Age art, a testament to the depth of talent that flourished during this remarkable period. His dedication to the subtle art of the monochrome banquet piece ensured his place as a respected master of the genre.

Conclusion: The Enduring Appeal of Quiet Beauty

Jan Jansz. van de Velde III stands as a testament to the specialized excellence that characterized Dutch Golden Age painting. Born into an artistic dynasty, he absorbed the lessons of his Haarlem predecessors, particularly Willem Claesz. Heda and Pieter Claesz., to become a distinguished exponent of the monochrome banquet piece. His works, with their restrained palettes, meticulous rendering of textures, and subtle interplay of light and shadow, invite quiet contemplation.

Though his life may have included periods of economic uncertainty, his artistic output demonstrates a consistent dedication to his craft. He captured the simple elegance of everyday objects, imbuing them with a sense of dignity and timelessness. While sometimes overshadowed by more flamboyant contemporaries or even by the prolific printmaking of his own father, Jan Jansz. van de Velde III's painted still lifes hold a secure and respected place in the history of art. They remind us of the profound beauty that can be found in the ordinary, a message that resonates as powerfully today as it did in the 17th century. His paintings are a quiet celebration of texture, light, and the transient pleasures of life, rendered with a skill that continues to captivate and impress.