Introduction: The Artist and His Time

The Dutch Golden Age, spanning roughly the 17th century, was a period of extraordinary artistic flourishing in the Netherlands. Fueled by economic prosperity, maritime trade, and a burgeoning middle class eager to adorn their homes, Dutch painters specialized in genres that captured the world around them with unprecedented realism and intimacy. Among the masters of still life painting, Evert Collier holds a distinct place, renowned for his captivating vanitas compositions and his mastery of trompe-l'oeil, the art of visual deception. Though his name sometimes appears in variations such as Edwaert, Edward, or Edwart, and his surname occasionally as Colyer or Kollier, the artist known to art history is predominantly Evert Collier, a painter whose works continue to fascinate viewers with their technical brilliance and profound symbolism.

Born in the Dutch Republic, Collier's life and career traversed several key artistic centers, including Leiden, Amsterdam, and finally London. His paintings are meticulous arrangements of objects – books, musical instruments, globes, skulls, letters, and ephemeral items like flowers or smoking candles – rendered with such precision that they seem tangible. Beyond mere representation, however, Collier's works are imbued with the philosophical and moral concerns of his time, particularly the vanitas theme, which served as a poignant reminder of the transience of life, the futility of earthly pursuits, and the inevitability of death. His skill in trompe-l'oeil further enhanced the impact of these themes, blurring the line between the painted world and the viewer's reality.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Evert Collier was born in Breda, a city in North Brabant, Dutch Republic. While the exact year of his birth was debated for some time, archival research points to his baptism on January 26, 1642. His early training remains somewhat obscure, as is common for many artists of the period. However, given the stylistic affinities in his early works, it is highly probable that he received his initial instruction in Haarlem, a major center for still life painting. Artists like Pieter Claesz and Willem Claesz. Heda, pioneers of the ontbijtje (breakfast piece) and the monochrome banquet still life, established a strong tradition of realistic depiction and subtle tonal harmonies in Haarlem.

It is likely that Collier absorbed the techniques and thematic concerns prevalent in this environment. The influence of painters such as Vincent Laurensz van der Vinne the Elder, another Haarlem artist known for his vanitas still lifes, can also be discerned in Collier's developing style. These early influences would have equipped him with the foundational skills in composition, rendering textures, and manipulating light and shadow that became hallmarks of his mature work. His formative years coincided with the peak of the Dutch Golden Age, a time when artistic innovation and specialization were highly valued.

The Leiden Years and the Vanitas Tradition

By 1667, Evert Collier is documented in Leiden, a city renowned for its university and intellectual atmosphere. This environment proved conducive to the development of his specialization in vanitas painting. Leiden had a strong tradition of fijnschilderij (fine painting), characterized by meticulous detail and a smooth, enamel-like finish, practiced by artists like Gerrit Dou, a student of Rembrandt. While Collier's style wasn't strictly fijnschilder, the emphasis on precision and careful rendering resonated with the Leiden school. In 1673, Collier became a member of the Leiden Guild of Saint Luke, an official recognition of his status as an independent master painter.

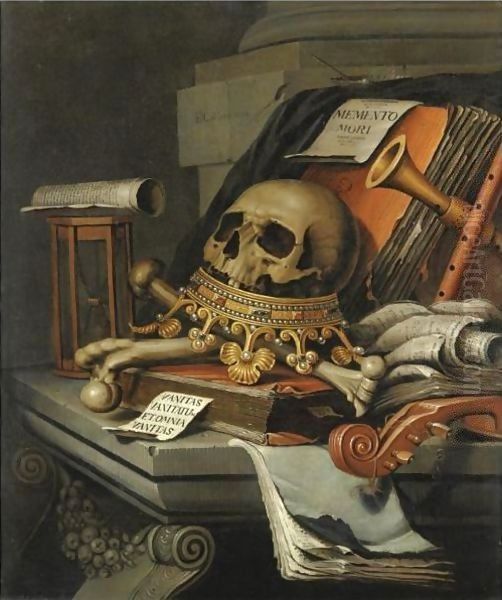

The vanitas genre, particularly popular in Leiden, drew heavily on Calvinist thought, emphasizing humility, piety, and reflection on mortality. Collier embraced this genre wholeheartedly. His vanitas paintings typically feature a collection of symbolic objects meticulously arranged on a table or ledge. Skulls are the most direct symbol of death (memento mori). Hourglasses, clocks, or guttering candles signify the relentless passage of time. Books, scientific instruments (like globes or astrolabes), and musical instruments often represent human knowledge, artistic pursuits, and worldly pleasures, all ultimately rendered fleeting and insignificant in the face of eternity. Soap bubbles, smoke, and wilting flowers further underscore the ephemeral nature of life and beauty. Collier arranged these elements with great care, creating compositions that were both visually engaging and intellectually stimulating, inviting viewers to contemplate deeper meanings.

Mastery of Trompe-l'oeil

Parallel to his work in the vanitas genre, Evert Collier excelled in trompe-l'oeil painting. Meaning "to deceive the eye" in French, this technique aims to create such a convincing illusion of reality that the viewer momentarily mistakes the painted objects for real ones. This required extraordinary technical skill in rendering textures, perspective, light, and shadow. Collier often favored specific types of trompe-l'oeil, most notably the "letter rack" or "quodlibet" (Latin for "what you please"). These paintings depict a collection of everyday items—letters, newspapers, prints, combs, sealing wax, quill pens, spectacles—seemingly tucked into straps nailed against a wooden board.

The appeal of trompe-l'oeil lay in its playful illusionism and its celebration of the painter's virtuosity. It was a visual game between the artist and the viewer. Collier's letter racks are remarkable for their convincing depiction of different materials: the crispness of paper, the worn texture of wood, the glint of metal, the softness of fabric ribbons. These works often contained personal or topical references, incorporating specific dates, names, or fragments of text that added layers of meaning or humor. Samuel van Hoogstraten, another Dutch artist associated with Rembrandt's circle, was also a notable practitioner of trompe-l'oeil, creating intricate perspective boxes and illusionistic wall paintings. Collier's focus on the letter rack format, however, became one of his signature contributions.

Notable Works and Symbolic Language

Evert Collier's oeuvre includes numerous paintings that exemplify his skill and thematic concerns. One of his most celebrated early works is the Vanitas Still Life with Books and Manuscripts and a Skull (1663), now housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. This painting showcases his ability to render textures—the aged parchment of books, the smooth, cold surface of the skull, the reflective quality of glass. The composition is carefully balanced, with the skull placed prominently, surrounded by symbols of learning and the arts, all under the shadow of mortality suggested by the snuffed candle or hourglass (often present in similar works). It serves as a powerful meditation on the limits of human knowledge and the transient nature of existence.

Another significant work, Still Life with a Volume of Wither’s “Emblemes” (1696), held by the Art Institute of Chicago, demonstrates his later style and his engagement with English culture after moving to London. The painting features an open copy of George Wither's A Collection of Emblemes, Ancient and Moderne, a popular English emblem book. Some interpretations suggest the inclusion of specific texts or objects in his London-period works carried subtle political commentary, perhaps reflecting on the relationship between the monarchy and Parliament, as hinted in the source material regarding a depiction of a king's speech. Works like Letter Rack (1693) highlight his trompe-l'oeil prowess, presenting a seemingly casual arrangement of documents and personal items with astonishing realism. His paintings in the Denver Art Museum, such as A Vanitas (1683) and Still Life: The Smell (1695), further illustrate his consistent engagement with these themes throughout his career.

Career Trajectory: Amsterdam and London

After his productive period in Leiden, Collier moved to Amsterdam around 1686. Amsterdam was the bustling commercial and artistic heart of the Dutch Republic, offering a larger market and different patronage opportunities. While details of his activities there are less documented, he continued to paint, likely adapting his style to suit the tastes of Amsterdam collectors, who perhaps favored richer and more elaborate still lifes, akin to the pronkstilleven (ostentatious still lifes) popularized by artists like Willem Kalf or Jan Davidsz. de Heem, although Collier largely remained true to his established themes.

A significant shift occurred in 1693 when Evert Collier relocated to London. This move reflects a broader trend of Dutch artists seeking opportunities abroad, particularly in England, where the art market was growing. Collier spent a considerable period in London, possibly until 1702, before returning briefly to Leiden, and then likely settling back in London for his final years. His time in England was fruitful. He found patrons among the English gentry and adapted his trompe-l'oeil and vanitas paintings to appeal to this new audience. This often involved incorporating English texts, newspapers (like the London Gazette), currency, and objects relevant to British culture and politics into his compositions. This adaptability demonstrates his business acumen as well as his artistic flexibility.

Collaboration and Contemporaries

During his time in England, Collier is known to have associated with other Dutch artists working there. Notably, he is linked with Pieter Gerritsz van Roestraeten, another Dutch painter who specialized in still lifes, particularly depictions of silver, and who also worked in the trompe-l'oeil style. The source mentions a collaboration at Newbattle Abbey, the seat of the Earls of Lothian (later Marquesses of Lothian), suggesting patronage from the Scottish aristocracy as well. Lord Lothian was indeed a known collector. Roestraeten, who was married to the niece of Frans Hals, the great Haarlem portraitist, had established a successful career in London, and his presence might have facilitated Collier's integration into the London art scene.

Placing Collier within the broader landscape of the Dutch Golden Age requires mentioning other key figures. While his direct teacher is unknown, his work evolved alongside contemporaries like the aforementioned Pieter Claesz, Willem Claesz. Heda, Samuel van Hoogstraten, and Vincent Laurensz van der Vinne. His Leiden period connects him geographically and thematically to the fijnschilders like Gerrit Dou and Frans van Mieris the Elder, even if his technique differed. His move to Amsterdam places him in the city dominated by Rembrandt van Rijn (though Rembrandt died in 1669, his influence persisted) and bustling with specialists like Willem Kalf and flower painters such as Rachel Ruysch and Jan van Huysum. In London, he joined a community of émigré artists, including figures like Sir Peter Lely (originally Dutch) and Sir Godfrey Kneller (originally German), who dominated portraiture, while artists like Roestraeten and Jan Wyck focused on other genres. Mentioning Johannes Vermeer (Delft/Leiden connection) and Jan Steen (Leiden genre painter) helps round out the picture of the rich artistic milieu Collier inhabited.

Later Life, Legacy, and Historical Evaluation

Evert Collier appears to have returned to Leiden for a period between 1702 and 1706, as indicated by signed and dated works placing him there. However, he seems to have spent his final years back in London. He died sometime shortly before September 8, 1708, the date he was buried at St James's Church, Piccadilly, London. His death in London underscores the international dimension of his later career.

Evert Collier's legacy rests on his significant contribution to the genres of vanitas and trompe-l'oeil still life painting. He was a highly skilled technician, capable of rendering objects with remarkable fidelity and creating compelling illusions. His vanitas works are poignant examples of a genre that reflected the deep moral and philosophical concerns of the Dutch Golden Age, reminding viewers of the transient nature of worldly existence. His trompe-l'oeil paintings, particularly the letter racks, are playful yet sophisticated demonstrations of artistic virtuosity, capturing fragments of everyday life with uncanny realism.

Historically, Collier is regarded as a significant and prolific painter within his specializations. While perhaps not reaching the revolutionary status of Rembrandt or Vermeer, he was a master craftsman who catered effectively to the tastes of his patrons in both the Netherlands and England. His work provides valuable insight into the cultural values, intellectual preoccupations, and material world of the 17th century. His paintings remain popular in museum collections and on the art market, admired for their meticulous detail, intriguing symbolism, and the enduring power of their illusionism. He successfully navigated the art markets of several major European cities, demonstrating an adaptability that contributed to his long and productive career. His work stands as a testament to the richness and diversity of still life painting during one of the most vibrant periods in European art history.

Conclusion: An Enduring Fascination

Evert Collier remains a compelling figure in the study of Dutch Golden Age art. His dedication to the meticulous craft of still life painting, combined with his engagement with profound themes of life, death, and the nature of reality, resulted in a body of work that continues to engage and intrigue. As a master of the vanitas genre, he captured the anxieties and philosophical reflections of his era with visual eloquence. As a practitioner of trompe-l'oeil, he pushed the boundaries of representation, delighting viewers with illusions that challenge perception. Spanning the artistic centers of Haarlem, Leiden, Amsterdam, and London, his career reflects the dynamic and international character of the 17th-century art world. The enduring appeal of his paintings lies in their exquisite detail, their rich symbolic language, and their timeless meditation on the human condition, presented through the captivating lens of illusion.