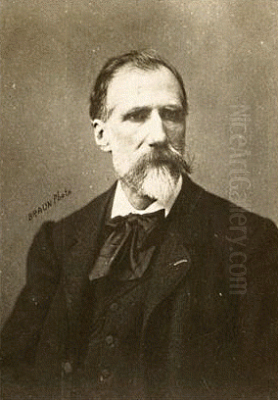

Jean Benner, a notable figure in nineteenth-century French art, carved a distinct niche for himself through his dedication to the Academic tradition, his evocative landscapes, particularly of Italy, and his finely rendered still lifes and mythological scenes. Born in 1836 and passing away in 1909, his life and career spanned a period of significant artistic evolution in Europe, yet he remained largely faithful to the classical principles that defined his training and aesthetic.

Early Life and Artistic Genesis

Jean Benner was born on March 28, 1836, in Mulhouse, a city in the Alsace region of eastern France, an area known for its rich cultural heritage and, at times, shifting national allegiances. His artistic inclinations were likely nurtured from a young age, as his father, also named Jean Benner (often referred to as Jean Benner the Elder), was a painter of Swiss origin. The elder Benner specialized in flower paintings and landscapes, reportedly influenced by the Dutch Masters, and it was under his initial tutelage that young Jean first learned the rudiments of art.

This familial introduction to the world of painting provided a foundational understanding of technique and composition. The Alsace region itself, with its picturesque landscapes and blend of French and Germanic cultures, might have also played a role in shaping his early visual sensibilities. However, like many aspiring artists of his generation, Benner recognized that Paris was the undisputed center of the art world, and he eventually made his way there to pursue formal artistic training and establish his career.

Parisian Training and Academic Foundations

In Paris, Jean Benner immersed himself in the rigorous environment of Academic art. He enrolled at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, the leading art institution in France, which championed a curriculum rooted in classical ideals, the study of anatomy, perspective, and the emulation of Old Masters. Here, he studied under respected masters such as Isidore Pils, known for his historical and military scenes, and later, he further honed his skills under the guidance of Jean-Jacques Henner, an Alsatian painter like himself, celebrated for his ethereal nudes and melancholic portraits, often characterized by a soft, sfumato technique.

Benner also benefited from the instruction of Léon Bonnat, a highly influential figure in the Academic art world, renowned for his powerful portraits and religious paintings, and who himself had absorbed Spanish realist influences. Some sources also mention Eugène Eck as one of his teachers, though Eck is a less universally recognized name compared to Pils, Henner, and Bonnat. This comprehensive training instilled in Benner a strong command of draughtsmanship, a respect for traditional subject matter, and a polished, refined technique – hallmarks of the Academic style. He shared his artistic journey, at least in part, with his twin brother, Emmanuel Benner, who also became a painter, often working in similar genres.

The Allure of Italy: Capri as a Muse

A significant chapter in Jean Benner's artistic development and thematic focus was his time spent in Italy, particularly on the island of Capri. Around 1867-1868, Jean and his brother Emmanuel moved to Capri, an island in the Bay of Naples that had become a magnet for artists, writers, and intellectuals from across Europe and America. Its dramatic cliffs, luminous grottos, vibrant local life, and the unique quality of its Mediterranean light offered inexhaustible inspiration.

Capri was more than just a picturesque location; it was an active artists' colony. Painters like Karl Wilhelm Diefenbach, Frederic Leighton, John Singer Sargent, and many others were drawn to its shores. For Benner, Capri became a recurring and beloved subject. He produced numerous landscapes capturing its scenic beauty, from its rugged coastlines to its sun-drenched vistas. These works often went beyond mere topographical representation, seeking to convey the atmosphere and idyllic charm of the island. His Italian landscapes, especially those of Capri, became one of his most recognized contributions.

Salon Success and Notable Works

The Paris Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, was the primary venue for artists to display their work and gain recognition during the 19th century. Jean Benner made his Salon debut in 1859 with a painting titled Fleurs (Flowers), a still life that showcased his early proficiency in this genre, likely reflecting his father's influence. This marked the formal beginning of his public career.

Throughout the subsequent decades, Benner became a regular exhibitor at the Salon. His works often received positive attention. A notable success came in 1876 with his mythological painting, Pallas Athéna effrayant les Athéniens à Lemnos (Pallas Athene Startling the Athenians at Lemnos). Critics lauded this piece for its "powerful depiction" and "bold attempt," indicating Benner's ambition to tackle grand historical and mythological themes, a cornerstone of Academic art.

Another significant work in this vein was Briseïs pleurant sur le corps de Patrocle (Briseis Weeping Over the Body of Patroclus), exhibited in 1878. This painting, drawn from Homer's Iliad, demonstrates his engagement with classical literature and his ability to convey pathos and drama within an Academic framework.

Perhaps one of his most famous and frequently reproduced works today is Salomé, painted around 1899. This depiction of the biblical femme fatale, holding the head of John the Baptist, was a popular subject in late 19th-century art, often explored by Symbolist painters as well. Benner’s interpretation is characterized by a classical elegance, a somewhat somber background that highlights the figure, and a focus on Salome's enigmatic expression. This painting is now housed in the Musée d'Arts de Nantes.

Other works, such as Poppies, further attest to his skill in still life, capturing the delicate beauty of flowers with precision and sensitivity. His oeuvre also included portraits, though he is less known for these compared to his landscapes and subject paintings.

Artistic Style and Techniques

Jean Benner's artistic style remained firmly rooted in the French Academic tradition. This meant a strong emphasis on meticulous draughtsmanship, smooth and polished brushwork that often concealed the artist's hand, and carefully constructed compositions. His figures were typically idealized, adhering to classical notions of beauty and proportion.

In his landscapes, particularly those of Capri, Benner demonstrated a keen sensitivity to light and atmosphere. He sought to capture the clarity of the Mediterranean light and the vibrant colors of the Italian scenery. While Academic in their finish, these landscapes often possessed a lyrical quality.

His still lifes, especially the flower paintings, show a dedication to detailed realism, capturing the texture and delicate forms of petals and leaves. There's an echo of the precision found in earlier Dutch and Flemish still life traditions, an influence possibly passed down from his father.

When tackling mythological or historical subjects, Benner employed the grand compositional strategies favored by Academic painters. These works often featured dramatic narratives, expressive figures, and a concern for historical or mythological accuracy in costume and setting, as understood at the time. He was adept at using light and shadow (chiaroscuro) to model forms and create a sense of depth and drama, as seen in Salomé, where the figure is illuminated against a darker, more mysterious background.

While not an innovator in the vein of the Impressionists or Post-Impressionists who were his contemporaries, Benner excelled within the established conventions of his training. He occasionally demonstrated a "bold attempt" in composition or subject, as noted by critics, suggesting a willingness to push slightly beyond conventional boundaries while still respecting the core tenets of Academic art.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu

Jean Benner worked during a vibrant and transformative period in French art. While he adhered to Academic principles, he was surrounded by artists exploring a multitude of styles. His teachers, Léon Bonnat and Jean-Jacques Henner, were significant figures. Bonnat was a highly successful portraitist and history painter, whose students included artists like Gustave Caillebotte, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and even the American Thomas Eakins. Henner, also Alsatian, was known for his distinctive, often melancholic style and his characteristic use of sfumato and red-haired figures.

Within the broader Academic sphere, Benner's contemporaries included giants like William-Adolphe Bouguereau, whose polished mythological scenes and sentimental genre paintings were immensely popular, and Jean-Léon Gérôme, famed for his Orientalist subjects and historical reconstructions. Alexandre Cabanel was another leading Academic painter, whose Birth of Venus was a sensation at the Salon of 1863.

Ernest Hébert, also a student at the École des Beaux-Arts and known for his melancholic Italian scenes and portraits, shared some thematic interests with Benner, particularly the Italian influence. Henri Fantin-Latour, while known for his group portraits of avant-garde artists, was also a master of still life, particularly flower paintings, providing an interesting point of comparison for Benner's own work in that genre.

The art world also saw the rise of Realism, championed by Gustave Courbet, who rejected Academic idealism in favor of depicting everyday life and ordinary people. Though stylistically different, Courbet was a powerful presence in the Parisian art scene. Later, Impressionism, with artists like Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, revolutionized painting by focusing on capturing fleeting moments and the effects of light and color, a stark contrast to the meticulous finish of Academic art.

Other notable painters of the era include Puvis de Chavannes, whose monumental, classicizing murals bridged Academicism and Symbolism; James Tissot, who depicted elegant scenes of contemporary high society; and Carolus-Duran, a fashionable portraitist. The international community in Paris and artist colonies like Capri also brought Benner into contact with artists from other countries.

The Benner Family and Artistic Connections

Artistry ran in the Benner family. Jean's twin brother, Emmanuel Benner (also 1836-1896, though some sources differ on his death year), was also a painter. Emmanuel, often known as Emmanuel Benner the Younger to distinguish him from an earlier family member, also specialized in historical subjects, allegories, and genre scenes, and frequently exhibited at the Salon. The brothers shared a studio for a time and, as mentioned, traveled to Capri together, indicating a close personal and professional relationship.

An interesting connection exists with the Bartholdi family. Jean Benner married Jeanne Bartholdi. This marriage brought him into the circle of the renowned Alsatian sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, the creator of the Statue of Liberty. It is plausible that Jean Benner's son, Emmanuel Michel Benner, was named in part to honor his uncle (Jean's twin) and perhaps carried the Bartholdi connection through his mother. The provided information suggests Emmanuel Michel Benner was the son of Jean Benner and Jeanne Bartholdi. This familial tie would have undoubtedly facilitated social and artistic interactions within a prominent Alsatian artistic network. The mention of a "Jean Bartholdi" in some contexts alongside Jean Benner's works might refer to another member of this extended family or a collaborator, though Auguste remains the most famous of that name.

Later Years, Death, and Legacy

Jean Benner continued to paint and exhibit throughout his life. While the exact date of his death has sometimes been cited as 1906, the more widely accepted and documented date is October 28, 1909, in Paris. He passed away at the age of 73, leaving behind a substantial body of work.

His paintings found their way into various public and private collections. Today, his works are held in French museums such as the Musée de Château-Musée in Nemours and the Musée d'Art et d'Histoire de Belfort. His Salomé in the Musée d'Arts de Nantes remains a key piece, and other works occasionally appear in exhibitions or at auction. The Städel Museum in Frankfurt, Germany, has also been cited in connection with his Salomé, possibly through loans or past exhibitions.

In the grand narrative of art history, Jean Benner is not typically counted among the revolutionary figures who drastically altered the course of art. He was, rather, a highly skilled and respected practitioner within the Academic tradition, a tradition that, despite being challenged by modernism, dominated official art institutions for much of the 19th century and continued to produce artists of considerable talent.

His legacy lies in his consistent production of well-crafted paintings that appealed to the tastes of his time. His landscapes of Capri contribute to the rich artistic record of that famed island, capturing its enduring allure. His mythological and historical scenes demonstrate his mastery of Academic conventions, while his still lifes reveal a delicate sensitivity to the natural world.

The evaluation of Academic art has fluctuated over time. Once dismissed by proponents of modernism, there has been a renewed scholarly and public interest in 19th-century Academic painters in recent decades, appreciating their technical skill, their engagement with classical and historical themes, and their role in the broader cultural landscape of their era. Jean Benner, within this context, is recognized as a competent and dedicated artist who contributed to the diverse tapestry of French art in the latter half of the 19th century. His connection to other artists, both through his training and family ties, further situates him within the intricate web of the Parisian and Alsatian art worlds.

Concluding Thoughts

Jean Benner's career exemplifies that of a successful Academic painter in 19th-century France. From his early training under the influence of his father to his formal education at the École des Beaux-Arts with masters like Bonnat and Henner, he absorbed the principles of classical art. His depictions of Italian landscapes, particularly Capri, his mythological compositions like Pallas Athene and Briseis, and his enduring Salomé, showcase his technical proficiency and his adherence to the aesthetic ideals of his time.

While the avant-garde movements of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism were forging new paths, Benner and his Academic colleagues like Bouguereau, Gérôme, and Cabanel continued to uphold a tradition that valued narrative clarity, idealized form, and polished execution. His work, found in museums and collections, serves as a testament to this significant, if sometimes overshadowed, stream of 19th-century art. He remains a figure worthy of study for his contribution to Academic painting and for his evocative portrayals of a world steeped in classical beauty and Mediterranean light.