Jessica Hayllar (1858-1940) stands as a notable figure among British women artists of the late Victorian and Edwardian eras. Her work, characterized by meticulous detail, a sensitive use of color, and an intimate focus on domestic life and floral subjects, offers a valuable window into the aesthetics and social nuances of her time. While perhaps not as widely known today as some of her male contemporaries, her consistent exhibition record at prestigious institutions and the enduring appeal of her paintings testify to her skill and the quiet dedication she brought to her art.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations in a Creative Household

Born in London on September 16, 1858, Jessica Hayllar was the eldest daughter of James Hayllar and Ellen Phoebe Cavell. Her father, James Hayllar (1829-1920), was himself a respected and successful painter, known for his genre scenes, portraits, and landscapes. He was a regular exhibitor at the Royal Academy and other major London venues. This familial environment was profoundly influential, as James Hayllar actively encouraged and tutored his children in the arts. Jessica, along with her three younger sisters – Edith (1860-1948), Mary (1863-1950), and Kate (1861-1900, though some sources differ on her lifespan and artistic output) – all became practicing artists, making the Hayllar household a veritable hub of creative activity.

The family spent many years at Castle Combe in Wiltshire, a picturesque village that provided ample inspiration, before later moving to Wallingford-on-Thames. It was in these settings that Jessica received her primary artistic training directly from her father. This apprenticeship model was common for women artists of the period, as formal art school education, while increasingly available, often had limitations for female students. James Hayllar's guidance would have instilled in Jessica a strong foundation in drawing, composition, and the oil painting techniques prevalent in Victorian academic art. She quickly proved to be a diligent and talented student, eventually becoming, as noted, one of the most prolific artists within this gifted family.

Themes of Domesticity and the Interior World

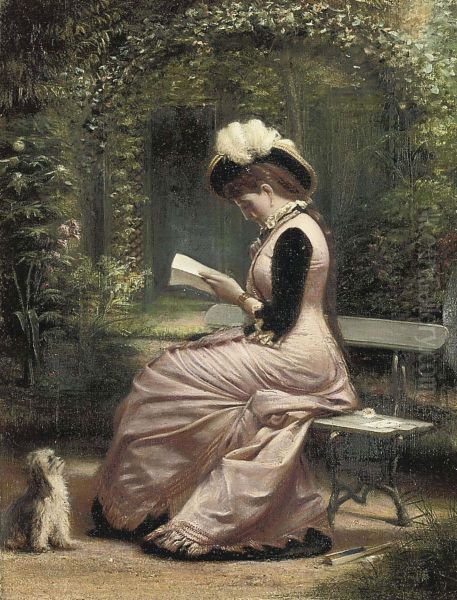

Jessica Hayllar's artistic output primarily centered on interior scenes, depictions of family life, and meticulous still lifes, particularly of flowers. Her genre paintings often capture quiet moments of everyday existence within the Victorian home. These scenes frequently feature family members, local villagers, or friends engaged in leisurely pursuits, conversations, or simple domestic tasks. The settings are typically well-appointed rooms, filled with the furnishings, textiles, and decorative objects characteristic of comfortable middle-class Victorian life.

A recurring and significant motif in her interior compositions is the use of windows and doorways. These elements are not merely architectural features but function as compositional devices that frame views, introduce light, and create a sense of spatial depth. They also subtly suggest a connection between the sheltered, private interior world and the world outside, hinting at narratives or emotional states. This interest in liminal spaces and the interplay of light filtering through openings is a hallmark of her work, lending a gentle dynamism to her often tranquil scenes. Her paintings evoke a sense of order, comfort, and the quiet rhythms of domesticity, themes that resonated strongly with Victorian audiences.

Her approach to genre painting can be seen in the context of a broader Victorian fascination with narrative and everyday life. Artists like William Powell Frith (1819-1909) with his sprawling social panoramas such as Derby Day or The Railway Station, or Augustus Egg (1816-1863) with his moralizing domestic dramas like Past and Present, set a precedent for depicting contemporary life. While Hayllar's work was generally smaller in scale and less overtly didactic, it shared an interest in capturing the human element within familiar settings. She can also be compared to other female artists focusing on domestic themes, such as Lady Laura Alma-Tadema (1852-1909), whose depictions of women and children in classical-inspired interiors were highly popular, or Helen Allingham (1848-1926), renowned for her charming watercolor scenes of rural cottages and gardens.

The Allure of Floral Still Life

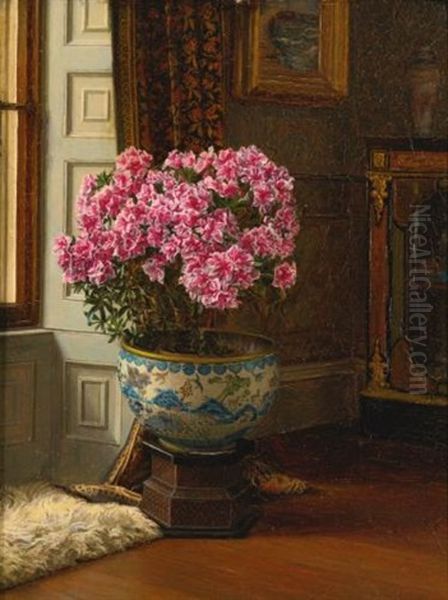

Alongside her genre scenes, Jessica Hayllar developed a significant reputation for her flower paintings. These still lifes often featured visually appealing pottery and porcelain vases, carefully arranged with blooms. Her compositions were more than simple botanical studies; they incorporated elements of the surrounding interior, with glimpses of rooms, furniture, or views through windows into gardens. This integration of still life with interior elements gave her floral works a distinctive character, setting them apart from more conventional, isolated still life arrangements.

Her flower paintings are often bathed in natural light, with sunlight streaming through windows, illuminating the textures of petals and the sheen of ceramics. This careful observation of light effects demonstrates her technical skill and her sensitivity to atmosphere. In her later years, particularly after a debilitating accident, her focus shifted more exclusively towards flower painting. Violets, in particular, became a favored subject. The choice of flowers, and the manner of their depiction, could carry symbolic weight in Victorian culture, though Hayllar's primary focus seems to have been on their aesthetic beauty and the technical challenge of capturing their delicate forms and colors.

The tradition of still life painting was well-established, with Dutch Golden Age masters like Jan van Huysum (1682-1749) or Rachel Ruysch (1664-1750) setting a high bar. In the 19th century, French artists like Henri Fantin-Latour (1836-1904) were producing exquisite flower paintings that gained international acclaim. While Hayllar's style was distinctly English and Victorian, her dedication to the genre contributed to its continued vitality.

Artistic Style and Technique

Jessica Hayllar's style is characterized by its precision, clarity, and attention to detail. Her brushwork is generally smooth and controlled, allowing for a high degree of realism in the rendering of textures, fabrics, and surfaces. This meticulous approach was a valued quality in much Victorian academic painting. She possessed a keen eye for observation, evident in the accurate depiction of domestic objects, architectural details, and the subtle nuances of human expression in her figures.

Her use of color was often described as bold and strong, yet harmonious. She skillfully managed complex color relationships within her compositions, particularly in her interiors, which were often rich with patterned wallpapers, carpets, and upholstery. The interplay of light and shadow was a key concern, and she adeptly used light to model forms, create atmosphere, and draw the viewer's eye to focal points. The inspiration she drew from the "luxurious decoration" of places like Castle Combe is evident in the richness and detail of her painted environments.

Compared to her father, James Hayllar, whose style was also rooted in Victorian realism, Jessica's work, especially her still lifes, sometimes exhibited a greater sense of freedom and a more personal interpretation of the subject. While trained by him, she developed her own distinct artistic voice. Her sisters, too, developed their own specializations; Edith Hayllar, for instance, also excelled in genre scenes, often depicting domestic activities with a similar attention to detail and narrative.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Key Works

Jessica Hayllar was a consistent and successful exhibitor throughout much of her career. Her works were regularly accepted at the prestigious annual exhibitions of the Royal Academy of Arts in London, from 1879 to 1915. This was a significant achievement, as the RA was the premier venue for artists seeking recognition and sales. To have work accepted year after year indicates a high level of professional standing.

Beyond the Royal Academy, she also exhibited with other important institutions, including the Society of British Artists (now the Royal Society of British Artists, RBA), the Institute of Oil Painters (ROI), and the Royal Manchester Institution. This broad exposure helped to establish her reputation among critics, collectors, and the art-buying public. Her paintings were reportedly highly valued by private collectors, indicating a steady market for her work.

Several specific works are noted in relation to her career. One of her early successes was A Summer Shower, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1882. This painting was reportedly well-received and helped to establish her as a promising young artist. The title suggests a domestic scene, perhaps figures seeking shelter or observing the rain from a window, themes well within her established repertoire.

Another painting, Far Away Thoughts (1885), also points to her interest in capturing introspective moments and psychological states within a domestic setting. The title itself evokes a narrative, inviting the viewer to speculate on the subject's reverie. Such works appealed to the Victorian taste for sentiment and storytelling in art.

Later in her career, as her focus shifted more towards floral subjects, works like A Pink Azalea (1904) would have showcased her skill in rendering the delicate beauty of flowers. These later still lifes, often painted with a continued sensitivity to light and color, formed an important part of her oeuvre.

The artistic environment in which Hayllar worked was vibrant and competitive. The Royal Academy exhibitions were major social and cultural events, featuring works by leading artists of the day such as Frederic Leighton (1830-1896), John Everett Millais (1829-1896), Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836-1912), and George Frederic Watts (1817-1904). While these artists often worked on a grander scale or with mythological and historical themes, the Academy also showcased a wide range of genre paintings, landscapes, and portraits, providing a platform for artists like Jessica Hayllar. Her father's association with figures like Leighton may have provided some indirect connections or awareness of the leading trends in the art world.

Later Life and Enduring Dedication

Jessica Hayllar never married and lived with her parents for much of her life. When her father, James Hayllar, eventually left Castle Combe and moved to Bournemouth, Jessica accompanied him. This continued proximity to her father likely reinforced her artistic pursuits.

A significant event in her life was a serious accident in 1900, reportedly a carriage accident, which had a lasting impact on her health. This incident may have contributed to her increasing focus on still life painting in her later years, as this genre could be pursued more easily within a studio setting without the physical demands of arranging complex figure compositions or seeking out varied locations. Despite these health challenges, she continued to paint.

After her father's death in 1920, Jessica moved to Sussex to live with her sister, Edith Hayllar MacKay (Edith had married). It was during these later years that her artistic output became predominantly focused on flower studies. She passed away on November 7, 1940, leaving behind a substantial body of work that reflects a lifetime of dedication to her craft.

Her contemporaries included other notable female artists who navigated the professional art world, such as Elizabeth Thompson (Lady Butler) (1846-1933), famous for her large-scale military scenes, and Louise Jopling (1843-1933), a portraitist and genre painter who also wrote an autobiography offering insights into the life of a female artist. While their subject matter often differed, their careers highlight the growing presence and achievements of women in the British art scene. The challenges for women artists were still considerable, but figures like Jessica Hayllar demonstrated that talent and perseverance could lead to a successful professional career.

Legacy and Reappraisal

Jessica Hayllar's art provides a charming and insightful glimpse into the domestic sphere of Victorian and Edwardian England. Her paintings are valued for their technical skill, their sensitive observation of everyday life, and their aesthetic appeal. While the grand narratives of history painting or the avant-garde movements of the early 20th century often dominate art historical accounts, the contributions of artists like Hayllar, who focused on more intimate and personal themes, are essential for a complete understanding of the period's artistic landscape.

In recent decades, there has been a growing interest in reassessing the contributions of women artists who may have been overlooked by earlier art historical narratives. Jessica Hayllar, along with her sisters, is part of this ongoing rediscovery. Her work is represented in public and private collections, and her paintings occasionally appear at auction, where they continue to attract interest.

Her legacy is that of a skilled and dedicated artist who found beauty and meaning in the everyday. Her depictions of tranquil interiors, family gatherings, and vibrant floral arrangements speak to a sensibility that valued home, nature, and the quiet moments of life. In a world often characterized by rapid industrial and social change, Hayllar's art offered a vision of stability, comfort, and refined aesthetic pleasure. She stands as a testament to the artistic talent that flourished within the Hayllar family and as a significant female voice in the rich tapestry of British Victorian painting, alongside artists like Rebecca Solomon (1832-1886) who also explored genre scenes, and later figures like Gwen John (1876-1939) who, though of a different stylistic inclination, also focused on intimate female portraits and interiors.

Jessica Hayllar's dedication to her craft, her ability to capture the nuances of domestic life with such precision and warmth, and her beautiful floral compositions ensure her a lasting place in the annals of British art. Her work continues to charm and engage viewers, offering a quiet yet compelling vision of a bygone era.