Mary Ellen Best (1809-1891) was a remarkable English watercolour artist whose work offers an intimate and detailed glimpse into the domestic interiors and social fabric of 19th-century Britain and, to some extent, Germany. While perhaps not as widely known during her lifetime as some of her male contemporaries, her prolific output and unique focus, particularly on the "downstairs" world of households, have earned her posthumous recognition as a significant documentarian of her era. Her paintings are cherished for their meticulous detail, charming compositions, and the invaluable record they provide of a bygone world.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations

Born in York, England, in 1809, Mary Ellen Best displayed an early aptitude for art. This was a period when artistic pursuits for women of her class were often encouraged as an accomplishment, though rarely as a serious profession. Best, however, pursued her passion with notable dedication. She received formal art lessons during her teenage years, notably while attending a boarding school in Little Blake Street (now Duplex Court), Bristol. This foundational training honed her skills in watercolour, a medium particularly popular in Britain at the time, championed by artists like J.M.W. Turner and John Constable for its versatility in capturing light and atmosphere, though Best would apply it to more intimate, interior scenes.

Her early life was marked by the typical experiences of a gentlewoman, but her keen observational skills were already developing. She was not content to merely sketch picturesque landscapes or sentimental portraits, common themes for amateur female artists. Instead, her gaze turned inwards, towards the spaces where daily life unfolded, a focus that would define her artistic career.

A Prolific Painter of Interiors

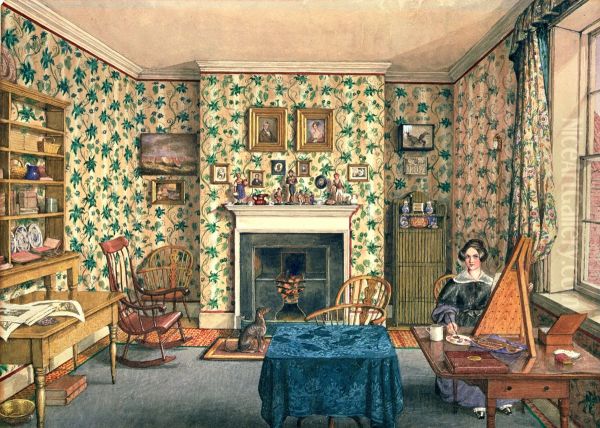

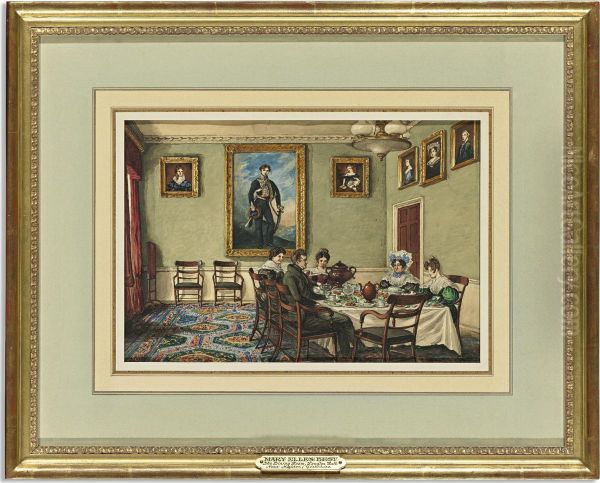

Mary Ellen Best's most significant contribution to art history lies in her detailed and often charming depictions of domestic interiors. She possessed an extraordinary ability to capture the essence of a room, not just its architectural features, but also its atmosphere and the personality of its inhabitants, often implied through the arrangement of furniture and personal belongings.

A substantial body of her work consists of studies of the Norcliffe family's residences, particularly Langton Hall in East Yorkshire. These paintings meticulously document the drawing rooms, dining rooms, music rooms, libraries, and even bedrooms of a prosperous gentry family. Unlike the grand, often impersonal, aristocratic portraits or "conversation pieces" by artists like Johann Zoffany from an earlier generation, Best's works feel more personal and accessible. They invite the viewer into these spaces, offering a sense of the daily rhythms and comforts of Victorian upper-middle-class life. The detail is often exquisite, from the patterns on the wallpaper and carpets to the specific items of furniture and decorative objects, providing invaluable information for social historians and decorative arts scholars.

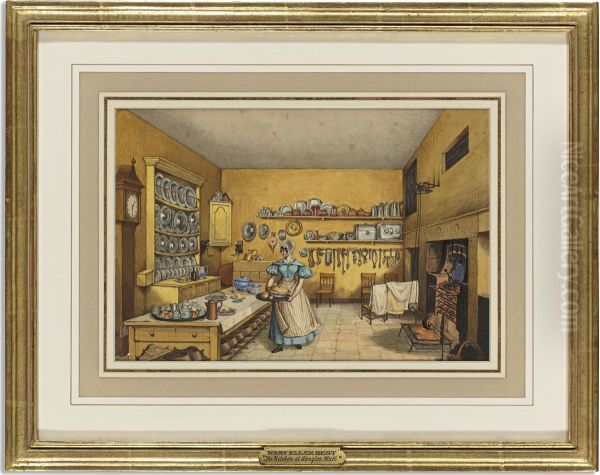

The "Below Stairs" Perspective

What truly set Mary Ellen Best apart from many of her contemporaries was her interest in the "below stairs" world – the kitchens, servants' quarters, and utility rooms that were the engine rooms of these grand houses. This was a realm rarely depicted with such directness and empathy by artists of her social standing. While artists like William Hogarth had earlier depicted servants, often in satirical or moralizing contexts, Best’s approach was more observational and matter-of-fact.

Her paintings of these spaces are not romanticized but are rendered with the same careful attention to detail as the grander rooms. We see kitchens bustling with activity (or captured in a quiet moment), sculleries, and pantries. This focus on the working areas of the home and, by extension, the lives of the servants, provides a more complete picture of 19th-century domesticity. It acknowledges the labor that underpinned the comfortable lifestyles of the gentry. This interest in the lives of ordinary working people aligns her, in spirit, with later Social Realist painters, though her style remained distinctly Victorian and less overtly political than, for example, the work of Hubert von Herkomer or Luke Fildes who often depicted scenes of poverty and labor with a strong social message.

Notable Works and Artistic Style

Among her most recognized works is The Hat Shop. This delightful watercolour captures the interior of a milliner's shop, bustling with bonnets and ribbons, and likely patrons or shop assistants. It showcases her skill in composing complex scenes with multiple figures and an abundance of detail, all rendered with a clarity and brightness characteristic of her watercolour technique. The painting is a charming vignette of commercial life and female fashion of the period.

Her series of paintings for the Norcliffe family at Langton Park, as mentioned, are collectively a major achievement. Individual pieces like The Drawing Room, Langton Hall or A Bedroom at Langton Hall are exemplary of her ability to convey both the specifics of a room and its lived-in quality. Her self-portrait, The Artist at Work, shows her at her easel, offering a rare glimpse into her own creative process and identity as a painter.

Best's style is characterized by precise draughtsmanship, a clear and often vibrant palette, and an almost miniature-like attention to detail. She used watercolour with great control, achieving smooth washes and crisp lines. There is a certain charming naivety in some of her figure drawing, but this is often overshadowed by the overall accuracy and documentary value of her scenes. Her perspective is usually straightforward, aiming for a faithful representation of the space. This contrasts with the more dramatic or romanticized interior scenes one might find in the work of some continental contemporaries, such as the German Biedermeier painters like Carl Spitzweg, who also depicted intimate domestic scenes but often with a more anecdotal or humorous narrative.

The German Connection: Documenting the Städel Museum

An interesting chapter in Best's artistic journey involves her time in Germany. Following her first visit to Frankfurt in 1835, she painted several views of the interior rooms of the Städel Museum (Städelsches Kunstinstitut). These watercolours proved to be of immense historical value, as they provided crucial visual information for the museum's later reconstructions, particularly after damage sustained in wartime. In 2018, these paintings were even used as a basis for a virtual reality recreation of the museum's historic interiors, a testament to their accuracy and enduring importance. This specific project highlights her role not just as an artist of domestic life, but as a careful recorder of significant public spaces as well.

Personal Life and Artistic Output

Mary Ellen Best's artistic output was significantly influenced by her personal life. She was a prolific artist, especially in her younger and middle years, creating over 1500 documented works. She actively sold her paintings and exhibited them, operating as a semi-professional artist, which was still relatively uncommon for women of her social standing. Her social network, built through family connections and travel, likely provided her with patrons and opportunities.

However, like many women artists of her time, the demands of family life eventually curtailed her artistic production. After the deaths of her grandmother and mother, and particularly after her marriage to Anthony St. John Charlton and the birth of her children, Henry and Marian (whom she also depicted in her art), her output noticeably declined. This pattern was common, as societal expectations often prioritized a woman's role as wife and mother over her professional or artistic ambitions. This contrasts with figures like Rosa Bonheur, the French animal painter, who largely eschewed marriage to dedicate herself fully to her art, or Lady Elizabeth Butler, famed for her large-scale military scenes, who managed to combine marriage with a high-profile artistic career, albeit with the support of an understanding husband.

Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

Mary Ellen Best worked during a vibrant period in British art. The Victorian era saw a burgeoning middle class with an appetite for art that reflected their lives and values. Genre painting – scenes of everyday life – was immensely popular. Artists like William Powell Frith created large, panoramic scenes of Victorian society (Derby Day, The Railway Station), while others like Augustus Egg explored narrative and moral themes in domestic settings.

In the realm of watercolour, artists like Myles Birket Foster were immensely popular for their charming, somewhat sentimentalized depictions of rural life and cottage interiors. While Best shared Foster's medium and a focus on domesticity, her work often feels more direct and less idealized. Her interest in depicting servants and working spaces also finds echoes in the work of other female artists like Emily Mary Osborn, who painted scenes such as Nameless and Friendless, highlighting the precarious position of women in Victorian society, or Rebecca Solomon, who also depicted contemporary social scenes.

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, with figures like Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, and William Holman Hunt, was also active during Best's lifetime, advocating for a return to the detail, intense colour, and complex compositions of Quattrocento Italian art. While Best's style was not directly Pre-Raphaelite, her meticulous attention to detail and her commitment to truthfully representing what she saw share a distant affinity with their principles, albeit applied to very different subject matter. Later watercolourists like Helen Allingham would continue the tradition of depicting charming English domesticity, particularly cottages and gardens, well into the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Rediscovery and Legacy

For many years after her death in 1891, Mary Ellen Best's work remained largely within private collections and was not widely known to the public or art historians. Her rediscovery began in the 1980s, significantly spurred by a large sale of her works at Sotheby's auction house. This brought her art to the attention of a new generation of collectors and scholars.

A pivotal moment in the reassessment of her work was the publication of Caroline Davidson's monograph, variously titled in editions but centrally known as Women's Worlds: The Art and Life of Mary Ellen Best (or similar variations like Mary Ellen Best: The Life of an English Watercolourist or Mary Ellen Best: The Art of Domestic Interior Scapes). Davidson's meticulous research and insightful analysis firmly established Best's importance as a unique visual chronicler of her time.

Today, Mary Ellen Best is recognized for her significant contribution to our understanding of 19th-century domestic life. Her paintings are valued not only for their artistic merit – their charm, detail, and skilled execution – but also for their invaluable documentary evidence. They offer a window into the material culture, social customs, and even the unspoken hierarchies of Victorian households.

Exhibitions and Collections

Works by Mary Ellen Best can be found in several public collections, most notably the York Art Gallery, which holds a significant collection of her paintings, including her self-portrait The Artist at Work and Salon Crompton. Her works have been featured in various exhibitions focusing on Victorian art, women artists, and domestic interiors. The Städel Museum in Frankfurt also holds her important views of its 19th-century interiors. The continued interest in her work is evident in its inclusion in exhibitions and its discussion in academic publications on 19th-century British art and social history.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

Mary Ellen Best's art provides a quiet but compelling narrative of 19th-century life. Through her dedicated practice of watercolour painting, she meticulously documented the world around her, from the well-appointed rooms of the gentry to the functional spaces of the household staff. Her unique perspective, particularly her willingness to depict the "below stairs" world, offers a more rounded and nuanced view of Victorian domesticity than many of her contemporaries.

While the societal constraints of her time may have ultimately limited the scale of her public career, the body of work she left behind is a rich and enduring legacy. Mary Ellen Best was more than just an accomplished amateur; she was a keen observer, a skilled artist, and an invaluable chronicler whose watercolours continue to delight and inform, securing her place as a distinctive voice in the chorus of Victorian art. Her paintings serve as a vivid reminder that history is not just made in grand events, but also in the quiet, everyday moments within the walls of a home.