Joachim Patinir, also known as Patenier, stands as a pivotal figure in the Northern Renaissance, celebrated primarily as a pioneer of landscape painting as an independent genre. Active in the bustling artistic hub of Antwerp during the early 16th century, Patinir's innovative approach to depicting expansive, atmospheric vistas redefined the role of landscape in art, elevating it from mere background to a dominant, expressive force. His work laid the groundwork for subsequent generations of landscape artists, profoundly influencing the trajectory of this genre in Western art.

Early Life and Emergence in Antwerp

The precise details of Joachim Patinir's birth and early training remain somewhat obscure, a common challenge when studying artists of this period. He is generally believed to have been born around 1480, with Dinant or Bouvignes in the French-speaking Southern Netherlands (modern-day Belgium) often cited as possible birthplaces. This region, characterized by dramatic river valleys and rocky outcrops along the Meuse River, may have provided early inspiration for the distinctive geological formations that feature so prominently in his later works.

By 1515, Patinir was registered as a master in the Guild of Saint Luke in Antwerp. This indicates he had completed his apprenticeship and was recognized as an independent artist capable of taking on commissions and training his own pupils. Antwerp, at this time, was rapidly becoming one of Europe's most important commercial and artistic centers, attracting talent from across the continent. The city's dynamic environment, with its wealthy merchant class and international connections, provided a fertile ground for artistic innovation and patronage.

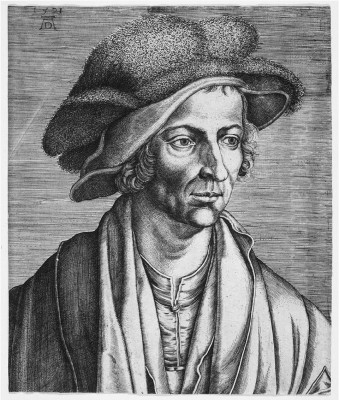

A significant contemporary account of Patinir comes from the renowned German artist Albrecht Dürer, who visited Antwerp in 1520-1521. Dürer's diary records his interactions with Patinir, whom he referred to as "Joachim, the good landscape painter" ("gut Landschaftmaler"). Dürer attended Patinir's second wedding in 1521 to Jeanne Nuyts, and even drew a portrait of him, though this drawing is now lost. Dürer's admiration underscores Patinir's established reputation as a specialist in landscape even during his lifetime. Patinir's life was relatively short; he died in Antwerp on or before October 5, 1524, the date on which his second wife was referred to as his widow.

The Genesis of a Style: The World Landscape

Joachim Patinir is credited with inventing and popularizing the "world landscape" (Weltlandschaft), a type of painting that presents an imaginary, panoramic view from a very high viewpoint, encompassing a vast and varied terrain. These landscapes are not depictions of specific, identifiable locations but rather composite scenes designed to evoke a sense of awe and wonder at the grandeur of creation, often imbued with religious or moralizing undertones.

Several key characteristics define Patinir's distinctive style. His compositions typically feature a tripartite color scheme to create atmospheric perspective: a brownish foreground, a greenish middle ground, and a bluish background for the distant mountains and sky. This formula, while not entirely new, was employed by Patinir with unprecedented consistency and effect, creating a convincing illusion of depth and recession. The horizon line is usually placed very high in the picture plane, allowing for an expansive vista that stretches far into the distance.

Fantastical rock formations are another hallmark of Patinir's work. These often sheer, craggy, and almost anthropomorphic structures punctuate the landscape, adding a sense of drama and otherworldliness. Rivers, lakes, and seas wind through these terrains, dotted with miniature towns, castles, and forests. While the landscapes dominate, human figures are almost always present, though they are typically small in scale relative to their surroundings. These figures often depict biblical scenes, such as the Rest on the Flight into Egypt, the Baptism of Christ, or the lives of hermit saints like Jerome or Anthony. The vastness of the landscape serves to emphasize the insignificance of humanity in the face of divine creation or the arduousness of a spiritual journey.

Patinir's approach marked a significant departure from earlier Netherlandish traditions, where landscape, while often beautifully rendered by artists like Jan van Eyck or Gerard David, primarily served as a backdrop for religious narratives or portraits. Patinir inverted this hierarchy, making the landscape the principal subject, with the narrative elements often playing a secondary, albeit thematically important, role. This innovation was crucial for the development of landscape painting as an independent genre.

Masterpieces of Vista and Vision

Though only a small number of paintings are confidently attributed to Patinir – perhaps around twenty – these works powerfully illustrate his innovative vision. Many bear his signature, "OPUS JOACHIM D. PATINIER," with the "D" likely referring to Dinant, his presumed place of origin.

Landscape with St. Jerome (c. 1515-1519, Prado Museum, Madrid) is one of his most iconic works. It showcases the saint in penitence within a vast, panoramic landscape filled with Patinir's characteristic elements: towering rock formations, a winding river, distant blue mountains, and meticulously detailed flora and fauna. The landscape itself seems to participate in the saint's spiritual contemplation, its wildness and solitude reflecting his ascetic life. Several versions of this theme exist, including notable examples in the National Gallery, London, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, attesting to its popularity.

The Flight into Egypt (c. 1515-1520, Museo del Prado, Madrid; another version in the Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp) is another recurring theme. Here, the Holy Family's journey is set against an expansive and perilous landscape. The Antwerp version, for instance, features a dramatic, almost surreal rock arch and a distant view of a pagan idol toppling, symbolizing the triumph of Christianity. The journey itself is dwarfed by the immensity of the natural world, emphasizing the vulnerability and faith of the protagonists.

Perhaps his most enigmatic and celebrated work is Landscape with Charon Crossing the Styx (c. 1515-1524, Prado Museum, Madrid). This painting, unique in its mythological subject matter, depicts the ferryman Charon transporting a soul across the river Styx. To the left lies Paradise, a serene, verdant landscape bathed in light, while to the right is Hell, a fiery, Boschian vision of torment. The central river and Charon's boat occupy a liminal space, and the soul's choice is made stark by the contrasting environments. The painting is a profound meditation on life, death, and salvation, conveyed almost entirely through the power of landscape.

The Baptism of Christ (c. 1515-1520, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna) places the biblical event in a typically Patiniresque expansive river landscape. Christ and John the Baptist are central but relatively small figures, surrounded by a world teeming with detail, from distant cities to lush forests. God the Father appears in the heavens above, sanctioning the event. The landscape serves not just as a setting but as a testament to the divine order of creation, sanctified by Christ's presence.

The Temptation of St. Anthony (c. 1520-1524, Prado Museum, Madrid) is another powerful example where the landscape amplifies the narrative. St. Anthony is shown beset by demonic temptations in a wild, isolated setting. The figures in this work are widely believed to have been painted by Quentin Matsys, a common collaborative practice at the time. The eerie, fantastical elements of the landscape contribute to the psychological drama of the saint's ordeal.

Anecdotes and Personal Glimpses

As mentioned, the most significant contemporary insights into Patinir's personality and standing come from Albrecht Dürer. During his stay in Antwerp from 1520 to 1521, Dürer formed a friendship with Patinir. Dürer's diary entries provide valuable, if brief, glimpses. He not only praised Patinir as a "good landscape painter" but also recorded social interactions.

On May 5, 1521, Dürer noted attending Patinir's second wedding to Jeanne Nuyts. Dürer's presence at such an important personal event suggests a degree of camaraderie and mutual respect between the two artists. Dürer also mentioned exchanging gifts with Patinir; he gave Patinir an engraving by Martin Schongauer and received some pigments in return. Furthermore, Dürer recorded that he drew Patinir's portrait, a common practice for him when meeting fellow artists, though, as stated, this portrait has not survived.

These interactions highlight Patinir's integration into the vibrant artistic community of Antwerp. Dürer, a towering figure of the Northern Renaissance, clearly held Patinir in high esteem, specifically for his landscape skills. This contemporary validation is crucial, as it confirms that Patinir's specialization was recognized and valued by his peers. Beyond Dürer's accounts, however, personal anecdotes about Patinir are scarce, leaving his art to speak most eloquently for him. The nature of his workshop, the specifics of his commissions, and his day-to-day life remain largely matters of scholarly inference based on the conventions of the time and the evidence of his paintings.

Artistic Lineage and Influences

Joachim Patinir did not emerge in an artistic vacuum. His work builds upon the rich tradition of Early Netherlandish painting, particularly its meticulous attention to detail and nascent interest in landscape. Artists of the previous generation, such as Jan van Eyck, Rogier van der Weyden, and Hans Memling, had already demonstrated a sophisticated ability to render naturalistic backgrounds, often filled with symbolic meaning. Gerard David, active in Bruges and later Antwerp, is often cited as a significant influence, particularly for his serene and atmospheric landscape settings in works like The Baptism of Christ (Groeningemuseum, Bruges). David's ability to integrate figures harmoniously within expansive natural environments likely resonated with Patinir.

However, the most profound influence on Patinir's more fantastical and moralizing landscapes is widely considered to be Hieronymus Bosch. Active in 's-Hertogenbosch, Bosch's imaginative and often nightmarish visions, populated with bizarre creatures and symbolic structures, clearly left a mark on Patinir, especially evident in works like Landscape with Charon Crossing the Styx or the hellish portions of some of his other paintings. While Patinir did not adopt Bosch's overtly didactic and densely populated allegories wholesale, he absorbed Bosch's capacity for creating otherworldly and psychologically charged environments. Patinir, however, channeled this into a more focused exploration of the landscape itself as a carrier of mood and meaning.

Patinir was a key figure in the Antwerp School, which was characterized by its dynamism, commercial success, and stylistic diversity in the early 16th century. This school saw the rise of specialists, and Patinir was arguably the first specialist landscape painter in the Netherlands. His innovations in landscape composition and atmospheric perspective became foundational for the genre.

Collaborations and Artistic Circle

The practice of collaboration between artists specializing in different areas was common in Antwerp during the 16th century. Patinir, renowned for his landscapes, frequently collaborated with figure painters to complete his compositions. This allowed each artist to focus on their strengths, resulting in works of high quality in both landscape and figural representation.

His most notable collaborator was Quentin Matsys (also known as Quinten Massys), a leading figure painter in Antwerp and a friend of Patinir. Matsys is documented as having painted the figures in Patinir's The Temptation of St. Anthony (Prado). The stylistic differences between the meticulously rendered, emotionally expressive figures and the expansive, atmospheric landscape are discernible yet harmoniously integrated. This partnership combined Matsys's skill in depicting human drama with Patinir's mastery of evocative settings.

Other artists with whom Patinir may have collaborated include Joos van Cleve, another prominent Antwerp master known for his religious paintings and portraits. Some scholars suggest that figures in certain Patinir landscapes show stylistic affinities with van Cleve's work. Bernard van Orley, a Brussels-based artist who also had connections with Antwerp, is another potential, though less certain, collaborator or influence, particularly in terms of integrating Italianate Renaissance elements, though Patinir's style remained fundamentally Northern.

While Patinir is not known to have had a large workshop with many documented pupils in the traditional sense, his influence was profound and widespread. His nephew, Herri met de Bles (also known as Hendrick Bles or Herry de Patenir), was a significant landscape painter who continued and developed Patinir's style, often incorporating similar high viewpoints, fantastical rock formations, and biblical or genre scenes. Frans Mostaert was another artist who followed in Patinir's footsteps, producing panoramic landscapes that clearly show his debt to the master. Patinir's impact, therefore, extended beyond direct tutelage to shaping a distinct school of landscape painting in the Netherlands.

A Landscape Innovator Among Peers

Joachim Patinir operated within a vibrant and competitive artistic milieu. Antwerp in the early 16th century was a melting pot of talent, with artists exploring various stylistic directions. While Patinir carved out a unique niche as a landscape specialist, he was surrounded by contemporaries who were also pushing artistic boundaries.

Quentin Matsys, his collaborator, was a dominant figure in Antwerp, known for his religious altarpieces, genre scenes, and portraits. Matsys's work, such as The Money Changer and His Wife (Louvre), shows a keen observation of human character and a mastery of oil painting technique that complemented Patinir's landscape skills. Their collaboration was one of mutual benefit rather than direct rivalry in the same specialization.

Hieronymus Bosch, though slightly earlier and based in 's-Hertogenbosch, cast a long shadow. His imaginative power and moralizing themes were influential, but Patinir's focus on the landscape itself as the primary conveyor of mood and meaning distinguished his approach. While Bosch used landscape to stage his complex allegories, Patinir made the landscape the allegory.

Other significant Netherlandish contemporaries included Jan Gossaert (also known as Mabuse), who was one of the first to travel to Italy and introduce Renaissance motifs and idealized nude figures into Northern art, marking the beginning of Romanism. Bernard van Orley in Brussels also embraced Italianate influences, working on large-scale altarpieces and tapestry designs. Their stylistic concerns were different from Patinir's, focusing more on monumental figures and classical forms, whereas Patinir remained rooted in the Northern tradition of detailed naturalism, albeit applied to imaginative landscape compositions.

Lucas van Leyden, active in the Northern Netherlands, was another important contemporary, renowned as both a painter and an exceptionally gifted printmaker. His work often featured innovative compositions and expressive figures, sometimes within detailed landscape settings, though landscape was not his primary focus in the way it was for Patinir.

In Germany, Albrecht Altdorfer, a contemporary and leading figure of the Danube School, was independently developing landscape painting. Altdorfer's Battle of Alexander at Issus (Alte Pinakothek, Munich), with its cosmic, panoramic vista, or his pure landscape etchings, show a parallel interest in the expressive power of nature. While direct influence between Patinir and Altdorfer is debated, their contemporaneous development of landscape highlights a broader shift in artistic sensibility across Northern Europe. Even in Italy, artists like Leonardo da Vinci were exploring atmospheric perspective and detailed landscape backgrounds, though the full emergence of independent landscape painting there would come later.

Patinir's unique contribution was his consistent and dedicated focus on the "world landscape," establishing it as a viable and respected genre. His peers recognized his specialized skill, as evidenced by Dürer's comments and the collaborative nature of his work. He was not so much in direct competition with figure painters like Matsys or Gossaert, but rather complemented their talents, offering a new type of artistic product that found a ready market.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Joachim Patinir's impact on the history of art, particularly landscape painting, is undeniable. Though his active career spanned less than a decade, his innovations were transformative. He is widely regarded as the first true specialist landscape painter in the Western tradition, elevating the genre from a subordinate background element to a primary subject capable of conveying profound emotional and spiritual meaning.

His development of the "world landscape" formula, with its high viewpoint, panoramic scope, atmospheric perspective using a three-color scheme, and characteristic fantastical rock formations, provided a model that was emulated and adapted by succeeding generations of artists. Followers like Herri met de Bles and Frans Mostaert directly continued his tradition.

More significantly, Patinir's work paved the way for the great Netherlandish landscape painters of the later 16th and 17th centuries. Pieter Bruegel the Elder, one of the most important artists of the Northern Renaissance, was profoundly influenced by Patinir's panoramic compositions. Bruegel adapted the world landscape concept for his iconic depictions of peasant life, seasonal cycles (like Hunters in the Snow), and biblical narratives set within expansive, naturalistic settings. While Bruegel's landscapes are often more grounded in observation of actual Netherlandish terrain, the structural debt to Patinir is evident.

The establishment of landscape as an independent genre, for which Patinir was a key catalyst, led to its flourishing in the Dutch Golden Age with artists like Jacob van Ruisdael and Meindert Hobbema. While their styles and subjects evolved, the foundational idea that landscape itself could be a worthy and expressive subject for art owes much to Patinir's pioneering efforts. His ability to imbue landscapes with mood, whether serene, dramatic, or mystical, resonated through centuries of art.

Patinir's paintings continue to captivate audiences with their imaginative scope and meticulous detail. They offer a window into a world where the natural and the fantastical intertwine, and where the grandeur of creation serves as a stage for human and divine dramas. His contribution was not just stylistic but conceptual, fundamentally changing how artists, patrons, and viewers perceived and valued the depiction of the natural world.

Conclusion

Joachim Patinir, the "good landscape painter" admired by Dürer, was far more than just a skilled craftsman. He was a visionary artist who fundamentally altered the course of Western art. By championing the "world landscape," he carved out a new artistic territory, demonstrating that the depiction of nature could be as compelling and meaningful as any historical or religious narrative. His panoramic vistas, imbued with atmosphere and often a sense of the sublime, invited viewers to contemplate not only the scene depicted but also humanity's place within the vastness of the cosmos. His legacy is etched into the very fabric of landscape painting, a genre he helped to define and elevate, ensuring his enduring importance in the annals of art history.