Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes stands as a pivotal figure in the history of art, a visionary painter and theorist who profoundly reshaped the genre of landscape painting at the turn of the 19th century. Born in Toulouse on December 6, 1750, and passing away in Paris on February 16, 1819, his career bridged the late Rococo, the stern Neoclassicism of the French Revolution and Napoleonic era, and the burgeoning Romantic sensibilities that would follow. Valenciennes was not merely a practitioner; he was an intellectual force, advocating for landscape painting's elevation to the status of history painting and pioneering practices that would become foundational for future generations of artists.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

Valenciennes's artistic journey began in his native Toulouse, but it was in Paris that his formal training took shape. He studied under history painters, notably Jean-Baptiste Despiaus and, more significantly, Gabriel-François Doyen. Doyen, a respected academician, would have instilled in Valenciennes the prevailing hierarchy of genres, which placed historical, mythological, and religious subjects at the apex, with landscape often relegated to a lesser, decorative role. This academic grounding in figure painting and grand compositions would paradoxically equip Valenciennes with the tools and ambition to challenge these very conventions from within the landscape genre itself.

His education was not confined to Parisian studios. Like many aspiring artists of his time, Valenciennes understood the crucial importance of a journey to Italy. This was considered an essential rite of passage, an opportunity to study firsthand the masterpieces of antiquity and the Renaissance, and to immerse oneself in the landscapes that had inspired centuries of artists.

The Italian Sojourns: Observation and Inspiration

Valenciennes first traveled to Italy around 1769, and made subsequent, extended stays, particularly in Rome, from 1771 and through the 1780s. These years were transformative. In Italy, he encountered the enduring legacies of the great classical landscape painters, Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain. From Poussin, he absorbed the principles of ordered, rational composition and the integration of historical or mythological narratives into idealized natural settings. From Claude, he learned the mastery of light, atmosphere, and the poetic evocation of an Arcadian past.

However, Valenciennes was not content to merely emulate these masters. He was profoundly interested in the direct observation of nature. During his Italian sojourns, he dedicated himself to an intensive practice of sketching en plein air (outdoors). He produced a remarkable body of oil sketches, small-scale studies painted directly from nature, capturing the fleeting effects of light, weather, and atmosphere on the Roman Campagna, the ruins of ancient temples, and the vibrant Italian skies. These sketches, often executed with a surprising freshness and immediacy, were not typically intended for public exhibition but served as a personal repository of visual information and a means of honing his observational skills. He focused on humble scenes and evocative ruins rather than grand, panoramic vistas, seeking the intrinsic character of the landscape.

One particularly dramatic experience during his time in Italy was witnessing the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 1779. He meticulously documented this event, not just as a passive observer but with a keen scientific and artistic interest. This firsthand encounter with the raw power of nature undoubtedly informed his later, more finished compositions depicting dramatic natural phenomena, such as his famous painting The Eruption of Vesuvius. His involvement in the archaeological excavations at Pompeii further deepened his connection to the classical past and its dramatic interplay with the natural world.

Return to Paris and Academic Ascent

Upon his definitive return to Paris around 1787, Valenciennes quickly established himself as a leading figure. He was admitted to the prestigious Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture in that same year, a significant achievement that signaled his acceptance within the official art establishment. His reception piece was likely a historical landscape, demonstrating his ambition to fuse the grandeur of history painting with the specificity of observed nature.

Valenciennes became a fervent advocate for landscape painting. He believed it capable of conveying profound intellectual and moral ideas, just like history painting. He sought to elevate its status within the Academy and in the eyes of the public. This mission was pursued not only through his own ambitious canvases but also through his influential role as a teacher and theorist.

The French Revolution brought significant upheaval to the artistic world. The Royal Academy was dissolved in 1793, a move that disrupted traditional structures of artistic training and patronage. Valenciennes navigated these turbulent times, and though an attempt in 1795 to establish a new Institute of Sciences and Arts, which would have included a dedicated section for landscape, did not immediately succeed in the way he envisioned, his efforts continued.

Theoretical Contributions: Codifying Landscape Art

Perhaps one of Valenciennes's most enduring legacies lies in his theoretical writings. In 1800, he published Élémens de perspective pratique, à l'usage des artistes, suivis de Réflexions et conseils à un élève sur la peinture, et particulièrement sur le genre du paysage (Elements of Practical Perspective for the Use of Artists, Followed by Reflections and Advice to a Student on Painting, and Particularly on the Landscape Genre). This treatise was a landmark publication.

In it, Valenciennes systematically laid out the principles of perspective, a crucial tool for creating convincing spatial recession in landscape. More innovatively, he articulated a philosophy of landscape painting. He distinguished between the "paysage portrait" (a direct, faithful depiction of a specific site) and the "paysage idéal" or "paysage historique" (an idealized, composed landscape, often incorporating historical or mythological figures and narratives). While he valued direct observation and the plein air sketch as essential preparatory steps, he ultimately championed the historical landscape as the highest form of the genre.

His writings emphasized the importance of understanding natural phenomena – the structure of clouds, the effects of light at different times of day, the character of trees and terrain. He encouraged students to build a "library" of oil sketches from nature, which could then be drawn upon in the studio to create more ambitious, composed works. His advice was practical and insightful, covering aspects from composition and color to the emotional and intellectual content of landscape art. This book became a standard text for generations of landscape painters and solidified his reputation as a leading pedagogue. He also taught landscape painting at the École des Beaux-Arts, further disseminating his ideas.

Artistic Style and Representative Works

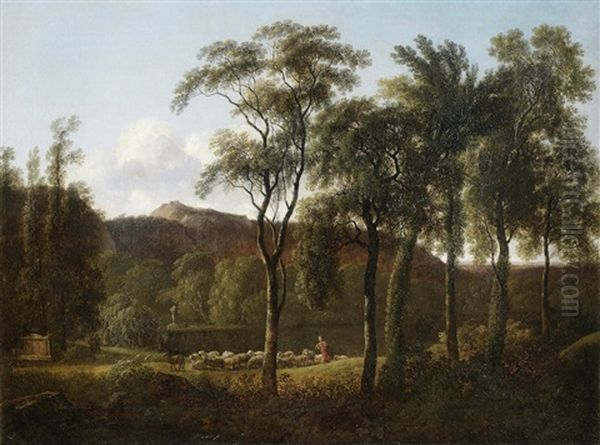

Valenciennes's artistic style is characterized by a synthesis of Neoclassical order and a keen sensitivity to natural effects. His finished salon paintings, often large in scale, typically depict idealized landscapes imbued with a sense of classical serenity or historical drama.

One of his most celebrated works is Cicero Discovering the Tomb of Archimedes (exhibited 1787). This painting exemplifies his concept of the historical landscape. The scene, set in a meticulously rendered Sicilian landscape, depicts the Roman orator Cicero identifying the overgrown tomb of the great Greek mathematician. The figures are relatively small, integrated into a grand, sweeping vista that speaks of the passage of time and the enduring power of nature and human intellect. The composition is balanced, the light clear, and the details of foliage and ancient architecture are rendered with precision.

Another significant work is Historical Landscape with Agrigentum (c. 1787), which showcases his ability to reconstruct an ancient cityscape within a plausible and evocative natural setting. His paintings often feature classical ruins, not merely as picturesque elements, but as symbols of history, transience, and the enduring legacy of civilization.

His depiction of The Eruption of Vesuvius (versions exist, one notable from 1813) demonstrates his capacity for capturing the sublime and terrifying aspects of nature, drawing on his personal experience. These works combine dramatic lighting and a sense of awe with a careful observation of geological phenomena.

While his large-scale historical landscapes were his public face, his numerous oil sketches reveal a more intimate and arguably more modern aspect of his art. Studies like Study of Sky and Clouds or View of Rome from the Villa Borghese are remarkable for their freshness, their bold handling of paint, and their focus on capturing transient atmospheric effects. These sketches, with their directness and emphasis on light and color, anticipate the concerns of later 19th-century landscape painters, including the Barbizon School and the Impressionists. An example like Ideal Classic Landscape with Washerwomen Around a Fountain shows his more composed, Claudian side, blending observed reality with an idealized classical structure.

Personal Life: Passion and Turmoil

Valenciennes's personal life was not without its complexities. Historical accounts suggest his marriage was unhappy, with his wife reportedly possessing a difficult temperament and showing little interest in his artistic pursuits. This domestic dissatisfaction may have led him to seek companionship and intellectual connection elsewhere.

He formed a significant and intense relationship with one of his students, Constance Mayer (1775-1821). Mayer was a talented artist in her own right, who later became a close collaborator and companion of Pierre-Paul Prud'hon, another prominent Neoclassical painter. Valenciennes's relationship with Mayer was reportedly a source of both inspiration and emotional turmoil. While she provided him with artistic camaraderie and support, the relationship was fraught with difficulties, allegedly including jealousy and infidelity on her part, leading to its eventual breakdown. The tragic suicide of Constance Mayer in 1821, two years after Valenciennes's own death, though primarily linked to her relationship with Prud'hon, casts a somber light on the intense emotional lives of artists in this period. Valenciennes was said to have been deeply affected by their separation and her subsequent fate, reportedly creating works in her memory.

Influence and Lasting Legacy

Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes's impact on the course of landscape painting was profound and multifaceted. Through his teaching and his influential treatise, he provided a theoretical framework that legitimized landscape as a serious intellectual pursuit and offered practical guidance for its execution.

He directly taught and influenced a generation of French landscape painters. Among his most notable students were Jean-Victor Bertin and Achille-Etna Michallon. Bertin himself became an important teacher, passing on Valenciennes's principles to artists like Camille Corot, who would become a key figure in the transition towards 19th-century naturalism. Michallon, though his career was tragically short, was a prodigious talent who won the first Prix de Rome for historical landscape in 1817, a category whose very existence owed much to Valenciennes's advocacy. The provided historical context also mentions students such as Achille-Etienne Michaux and Michault Leblon, who would have been part of his circle of influence.

Valenciennes's emphasis on plein air sketching, while not entirely new (artists like Claude Gellée, known as Claude Lorrain, and later Joseph Vernet, had made outdoor studies), was systematized and promoted by him with unprecedented vigor. This practice became increasingly central to landscape painting in the 19th century. The artists of the Barbizon School, such as Théodore Rousseau and Charles-François Daubigny, who sought a more direct and unidealized engagement with nature, built upon the foundations laid by Valenciennes and his students.

Further down the line, the Impressionists, including Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Alfred Sisley, took the practice of plein air painting to its logical conclusion, making the finished artwork itself outdoors to capture the fleeting impressions of light and color. While their aesthetic aims differed significantly from Valenciennes's Neoclassicism, his pioneering work in outdoor oil sketching and his focus on atmospheric effects can be seen as an important precursor. Contemporaries like Hubert Robert, known for his picturesque views of ruins, also shared some common ground with Valenciennes in their subject matter, though Valenciennes brought a more rigorous, theoretical approach to the historical landscape.

His influence extended beyond France. Artists across Europe who sought to combine classical ideals with a fresh observation of nature found inspiration in his work and writings. His advocacy for the "historical landscape" helped to create a space for ambitious, large-scale landscape paintings in official exhibitions and collections.

Conclusion: A Bridge to Modernity

Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes was more than just a skilled painter of Italianate scenes. He was a thinker, an innovator, and a dedicated educator who fundamentally changed the way landscape painting was perceived and practiced. He successfully argued for its intellectual respectability, bridging the gap between the idealized visions of Poussin and Claude and the more direct, observational approaches that would come to define much of 19th-century art.

His insistence on the importance of direct study from nature, particularly through oil sketching, provided a vital link to the future, anticipating the concerns of Romanticism, Realism, and Impressionism. While his finished works adhered to Neoclassical principles of order and idealization, his sketches reveal a remarkably modern sensibility. By championing both rigorous academic training and intimate communion with the natural world, Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes carved out a unique and enduring place in the annals of art history, solidifying his status as a true pioneer of modern landscape painting. His legacy is not just in his beautiful canvases and insightful writings, but in the very evolution of how artists see and represent the world around them.