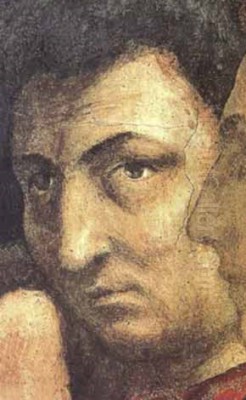

Tommaso di Ser Giovanni di Mone Cassai, known to posterity as Masaccio, stands as one of the most pivotal figures in the history of Western art. Born on December 21, 1401, in San Giovanni Valdarno, Tuscany, his life was tragically short, ending in Rome around the late autumn of 1428. Yet, in a career spanning little more than a decade, Masaccio revolutionized painting, steering it away from the elegant but stylized forms of Gothic art towards a new naturalism, a profound understanding of human form and emotion, and a groundbreaking use of perspective that would define the course of the Early Italian Renaissance. His nickname, Masaccio, meaning "Clumsy Tom" or "Big Tom," perhaps hinted at a certain disregard for worldly affairs or a robust, unrefined energy, but in his art, there was nothing clumsy; only a powerful, clear-sighted vision.

The Florentine Crucible: Early Life and Artistic Formation

Masaccio's father, Ser Giovanni di Mone Cassai, was a notary, and his mother, Jacopa di Martinozzo, came from a local innkeeping family. His father died when Masaccio was only five, and his mother subsequently remarried. These early years, possibly marked by some financial instability, saw the family remain in San Giovanni Valdarno. Little is definitively known about Masaccio's earliest artistic training. It is presumed he moved to Florence, the vibrant heart of the burgeoning Renaissance, around 1418 or shortly thereafter, the city that would become the primary stage for his revolutionary work.

Florence in the early 15th century was a ferment of artistic and intellectual innovation. The legacy of Giotto di Bondone, who a century earlier had reintroduced a sense of weight and naturalism to painting, was still palpable. More immediately, Masaccio entered an environment dominated by the pioneering spirits of the architect Filippo Brunelleschi and the sculptor Donatello. These two artists were his elder contemporaries and, by all accounts, profound influences. Brunelleschi was systematically exploring the principles of linear perspective, a mathematical system for creating the illusion of three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface. Donatello, in his sculpture, was achieving unprecedented levels of psychological realism and anatomical accuracy, imbuing his figures with a new sense of human dignity and physical presence. Masaccio absorbed these lessons, translating their three-dimensional insights into the medium of paint. He likely also encountered the work of other Florentine painters such as Lorenzo Monaco and Gentile da Fabriano, whose International Gothic style, with its emphasis on graceful lines and decorative richness, provided a stark contrast to the direction Masaccio would take.

The Dawn of a New Vision: Early Works

Masaccio is first documented as a painter in Florence on January 7, 1422, when he enrolled in the Arte de' Medici e Speziali, the painters' guild. One of his earliest attributed works, and his first securely dated one, is the San Giovenale Triptych, dated April 23, 1422, now housed in the Cascia di Reggello. This altarpiece, depicting the Virgin and Child with Saints Bartholomew, Blaise, Juvenal, and Anthony Abbot, already shows departures from prevailing Gothic conventions. The figures possess a solidity and a solemn dignity, and there's an attempt at creating a unified, albeit still somewhat archaic, spatial setting. The Christ Child, for instance, is depicted with a naturalism quite distinct from the miniature adult forms often seen previously.

Around 1424, Masaccio collaborated with an older, more established artist, Masolino da Panicale, on the Virgin and Child with Saint Anne (also known as the Sant'Anna Metterza), now in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence. Art historians generally attribute the more robust and spatially coherent figures of the Virgin and Child to Masaccio, while the more delicate and Gothic-inflected Saint Anne is often given to Masolino. Masaccio's contribution here is striking: the Virgin is a monumental figure, her form convincingly modeled through light and shadow, and the Christ Child is again rendered with a remarkable, almost sculptural, realism. This collaboration highlights the stylistic differences between the two artists and underscores Masaccio's rapidly developing, innovative approach.

The Brancacci Chapel: A Monument of Renaissance Painting

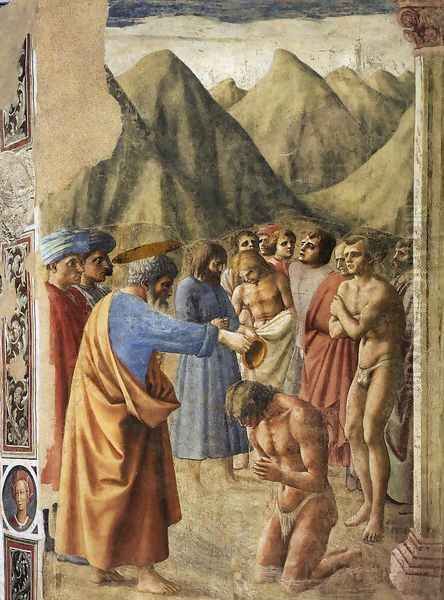

Masaccio's most extensive and arguably most influential work is the fresco cycle in the Brancacci Chapel in the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence. Commissioned by the wealthy silk merchant Felice Brancacci, likely around 1424-1425, the frescoes depict scenes from the life of Saint Peter. Masaccio again worked alongside Masolino, but Masolino departed for Hungary in September 1425, leaving Masaccio to continue much of the work alone until he himself left for Rome in 1428. The chapel remained unfinished for decades, eventually being completed by Filippino Lippi in the 1480s.

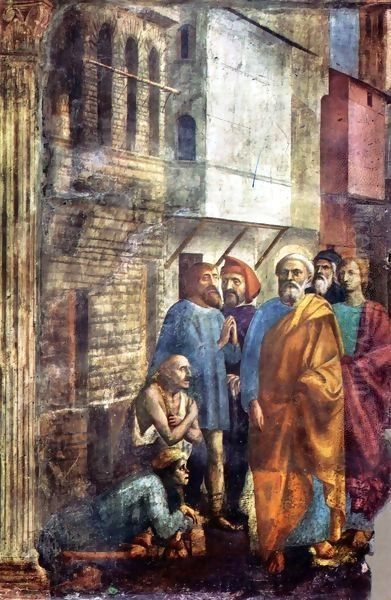

The Brancacci Chapel frescoes are a watershed in the history of art. Here, Masaccio fully implemented his revolutionary ideas. He created a consistent, illusionistic space governed by linear perspective, often using a single, unified light source that casts realistic shadows, giving the figures unprecedented volume and weight. His figures are not ethereal beings but solid, psychologically present individuals, their emotions conveyed through gesture and facial expression.

The Tribute Money is perhaps the most celebrated scene in the chapel. It masterfully depicts three episodes from the Gospel of Matthew in a continuous narrative: Christ instructing Peter to find a coin in the mouth of a fish, Peter catching the fish, and Peter paying the temple tax. The figures are arranged in a semi-circle around Christ, creating a powerful sense of depth. The architecture recedes according to perspective principles, and the landscape, though simple, contributes to the spatial illusion. The figures themselves are individualized, their expressions and postures varied and natural. The use of light, seemingly emanating from a single source to the right (corresponding to the chapel's actual window), models the forms and integrates them into the environment.

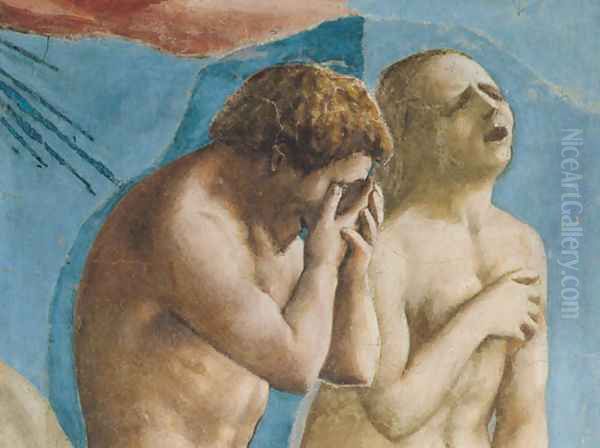

Another iconic fresco is the Expulsion from the Garden of Eden. This raw, emotionally charged depiction of Adam and Eve, shamed and anguished as they are driven out by an angel, is a testament to Masaccio's ability to convey profound human feeling. Eve's cry of despair and Adam's buried face convey their desolation with an intensity rarely seen before. Their nudity, rendered with anatomical understanding, emphasizes their vulnerability. This work stands in stark contrast to Masolino's more graceful and less emotionally fraught Temptation of Adam and Eve on the opposite wall.

Other significant scenes by Masaccio in the Brancacci Chapel include St. Peter Healing the Sick with His Shadow, where the figures seem to react physically to Peter's passing presence, and the Baptism of the Neophytes, notable for the shivering figure of a youth awaiting baptism, a touch of naturalistic observation that was revolutionary for its time. The Brancacci Chapel became a veritable school for later generations of artists, including giants like Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael, who all studied and sketched Masaccio's figures there.

The Holy Trinity: A Masterpiece of Perspective and Theology

Concurrent with his work in the Brancacci Chapel, or perhaps shortly thereafter (c. 1425-1427), Masaccio painted his fresco of The Holy Trinity in the Church of Santa Maria Novella, Florence. This work is considered one of the earliest and most perfect demonstrations of linear perspective in painting. The fresco depicts God the Father supporting the crucified Christ, with the Holy Spirit as a dove between them. Flanking the cross are the Virgin Mary and Saint John the Evangelist. Below them, outside the sacred space, are the kneeling donor figures, likely members of the Lenzi or Berti family. At the very bottom, a skeleton lies on a sarcophagus with the inscription: "IO FU[I] G[I]A QUEL CHE VOI S[I]ETE E QUEL CH['] I[O] SONO VO[I] A[N]CO[R] SARETE" ("I once was what you are, and what I am you also will be").

The illusion of a deep, barrel-vaulted chapel receding into the wall is astonishingly convincing, achieved through the precise application of Brunelleschi's principles of perspective. The vanishing point is located at the eye level of a viewer standing in the nave, drawing them into the sacred scene. The figures are monumental and solemn, their forms modeled with a strong sense of chiaroscuro. The memento mori of the skeleton serves as a stark reminder of mortality and the promise of salvation through faith, a common theme in funerary art. The Holy Trinity is not just a technical tour-de-force but a profound theological statement, seamlessly integrating art, science, and faith. It influenced countless artists, including Andrea Mantegna and Piero della Francesca, who further developed the use of perspective.

Other Works and Roman Sojourn

Other works from Masaccio's Florentine period include panels for the Pisa Altarpiece (1426), commissioned for the Carmelite Church in Pisa. Though now dismembered and scattered across various museums, its central panel, the Madonna and Child (National Gallery, London), shows a majestic Virgin and a robust, playful Christ Child, again demonstrating Masaccio's mastery of form and naturalism. The predella panels, such as the Adoration of the Magi (Gemäldegalerie, Berlin), showcase his ability to handle complex group compositions and narrative detail within a perspectival framework.

In 1423, Masaccio is documented in Rome, possibly in connection with the Jubilee year. He returned to Florence but then traveled back to Rome in 1428, perhaps to work on a commission with Masolino at San Clemente or for a polyptych for Santa Maria Maggiore (the Colonna Altarpiece, of which panels survive). It was in Rome that his life was cut short. Giorgio Vasari, the 16th-century biographer of artists, recounts a rumor that Masaccio was poisoned out of professional jealousy, but this remains unconfirmed. The exact date and circumstances of his death are obscure, but it likely occurred in the late autumn of 1428, when he was only about twenty-seven years old.

The Character of the Artist: "Sloppy Tom"

Vasari describes Masaccio as being so devoted to his art that he cared little for worldly matters, including his personal appearance or financial affairs, hence the nickname "Masaccio." This image of an artist consumed by his creative passion, perhaps somewhat unkempt and absent-minded, has persisted. Whether entirely accurate or a romanticized trope, it underscores the intensity of his artistic focus. His surviving works certainly attest to a mind deeply engaged with the problems of representation, light, space, and human emotion. He was not merely applying rules but thinking through them, pushing the boundaries of what painting could achieve.

Masaccio's Enduring Legacy and Influence

Despite his tragically short career, Masaccio's impact on the course of art was immense and immediate. He effectively laid the foundations for much of Italian Renaissance painting. His innovations were not isolated tricks but part of a coherent vision that synthesized the scientific understanding of perspective with a new, humanistic appreciation for the natural world and the dignity of the individual.

Artists in Florence were quick to recognize the power of his work. Fra Angelico, though his temperament led him to a more serene and spiritual art, absorbed Masaccio's lessons in figure construction and spatial clarity. Fra Filippo Lippi, another Carmelite friar who would have known the Brancacci frescoes intimately, developed a more lyrical style but owed much to Masaccio's naturalism and sense of volume. Paolo Uccello became famously obsessed with perspective, perhaps inspired by Masaccio's pioneering efforts. Andrea del Castagno pushed Masaccio's monumental figural style towards an even more rugged and powerful expressionism. Domenico Veneziano and Piero della Francesca, who may have encountered Masaccio's work or his influence through other artists, became masters of light and perspective, building upon the foundations he had laid.

Further afield, artists like Andrea Mantegna in Padua and later Venice, created works of stunning perspectival illusionism that are indebted to the Florentine breakthroughs pioneered by Masaccio and Brunelleschi.

The High Renaissance masters, born decades after Masaccio's death, revered him. Leonardo da Vinci, in his notebooks, praised Masaccio for demonstrating "by his perfect works how those who take for their standard anyone but nature – the mistress of masters – weary themselves in vain." Leonardo's own use of chiaroscuro and sfumato, his profound observation of human anatomy and psychology, can be seen as an extension of Masaccio's naturalistic impulse.

Michelangelo Buonarroti, as a young artist, famously studied and copied figures from Masaccio's Brancacci Chapel frescoes. The monumentality, the anatomical power, and the expressive force of Masaccio's figures, such as Adam and Eve in the Expulsion, resonated deeply with Michelangelo's own artistic temperament and found echoes in his Sistine Chapel ceiling and his sculptures.

Raphael Sanzio, known for his harmonious compositions and graceful figures, also learned from Masaccio, particularly in the arrangement of figures in space and the creation of convincing narrative scenes. His Stanza della Segnatura frescoes in the Vatican, for example, show a sophisticated understanding of perspective and figural grouping that builds upon the Early Renaissance tradition.

Even beyond Italy, Masaccio's revolution eventually spread, contributing to the broader European Renaissance. His emphasis on direct observation of nature, the rational construction of space, and the depiction of human beings with weight, dignity, and psychological depth became cornerstones of Western painting for centuries.

Conclusion: The Father of Modern Painting

Masaccio's premature death was an undeniable loss to the art world. One can only speculate what more he might have achieved had he lived longer. However, in his brief but brilliant career, he accomplished a revolution. He took the tentative steps towards naturalism made by Giotto and, armed with the new science of perspective and a profound empathy for the human condition, forged a new language for painting. He endowed his figures with a physical and psychological presence that was unprecedented, placing them in rationally constructed, believable spaces.

He was, as many art historians have called him, one of the true "fathers" of Renaissance painting. His work in the Brancacci Chapel and The Holy Trinity fresco are not just masterpieces of their time but enduring monuments that continue to inspire awe and instruct. Masaccio demonstrated that painting could be a high intellectual art, capable of conveying complex ideas and profound emotions with clarity and power. His legacy is not merely in the specific techniques he pioneered but in the new way of seeing and representing the world that he bequeathed to generations of artists who followed. In the grand narrative of art history, Masaccio's star, though it burned for only a short time, shone with an intense and transformative light, illuminating the path for the artistic achievements of the Renaissance and beyond.