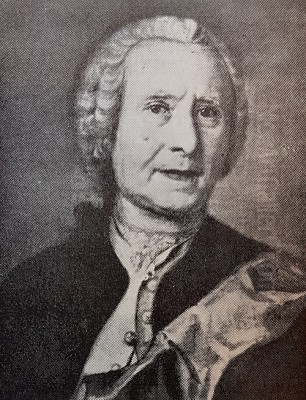

Johann Henrik Scheffel (1690–1781) stands as a significant figure in the annals of Swedish art, particularly renowned for his insightful and meticulously rendered portraits. Active during a transformative period in Swedish history, often referred to as the Age of Liberty and the burgeoning Enlightenment, Scheffel's work provides a valuable visual record of the prominent individuals who shaped the nation's scientific, cultural, and political landscape. His artistic contributions extended beyond mere likeness; they captured the spirit of an era characterized by intellectual curiosity and a burgeoning national identity. Through his canvases, we encounter the faces of scientists, military leaders, academics, and cultural figures, each depicted with a clarity and psychological depth that speaks to Scheffel's skill and his understanding of his subjects.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in the historic city of Wismar, then under Swedish rule, in 1690, Johann Henrik Scheffel's early life and artistic inclinations were shaped by the cultural currents of Northern Europe. Wismar, a Hanseatic port, provided a cosmopolitan environment, though details of his earliest training there remain somewhat obscure. It is known, however, that his formative artistic journey took him to several key European artistic centers, a common practice for aspiring artists of the period seeking to broaden their horizons and hone their skills.

Scheffel is documented to have undertaken studies in Germany, likely absorbing the prevailing late Baroque and early Rococo influences. His travels and studies extended to Paris, the undisputed epicenter of European art and culture in the 18th century. In Paris, he would have been exposed to the sophisticated portraiture traditions of masters like Hyacinthe Rigaud and Nicolas de Largillière, whose grand and expressive depictions of royalty and aristocracy set the standard across the continent. Further studies in Brabant, encompassing parts of modern-day Belgium and the Netherlands, would have acquainted him with the rich legacy of Flemish and Dutch realism, known for its meticulous detail and psychological penetration, a tradition stretching back to artists like Anthony van Dyck and Rembrandt van Rijn.

This diverse educational background equipped Scheffel with a versatile technical foundation and a broad understanding of contemporary European artistic trends. By the time he established himself in Sweden, he brought with him a synthesis of these influences, which he would adapt to the specific tastes and cultural context of his adopted homeland. His arrival in Sweden coincided with a period of growing demand for portraiture, fueled by an increasingly affluent and influential class of nobles, burghers, and intellectuals.

Arrival in Sweden and the Artistic Milieu

Scheffel established himself in Stockholm by 1723, a city buzzing with new ideas and artistic endeavors. The Great Northern War had recently concluded, and Sweden was entering its "Age of Liberty" (Frihetstiden, 1719-1772), a period marked by parliamentary rule, increased civil freedoms, and a flourishing of the arts and sciences. This era saw a shift away from the absolute monarchy and a greater emphasis on intellectual pursuits, creating a fertile ground for artists like Scheffel.

The artistic scene in Sweden at this time was vibrant, though perhaps not as overtly flamboyant as in Paris. Portraiture was the dominant genre, serving to commemorate individuals, display status, and record lineage. Scheffel entered a field populated by notable painters. Georg Engelhard Schröder had been a leading portraitist, and David Klöcker Ehrenstrahl, though from an earlier generation, had laid a strong foundation for Swedish Baroque portraiture. Contemporaries included Olof Arenius, with whom Scheffel would later teach, and the highly skilled pastellist Gustaf Lundberg, who brought a delicate Rococo sensibility from Paris. Later in Scheffel's career, figures like Alexander Roslin and Carl Gustaf Pilo would rise to international fame, showcasing the strength of Swedish painting.

Scheffel's style, characterized by its clarity, realism, and often unembellished directness, found favor among patrons who appreciated a less ostentatious, more sincere form of representation. He quickly gained a reputation for his ability to capture not just a physical likeness but also the character and intellectual bearing of his sitters.

Scheffel's Role at the Royal Drawing Academy

A significant aspect of Johann Henrik Scheffel's contribution to Swedish art was his involvement with the nascent Royal Swedish Academy of Arts, initially known as the Royal Drawing Academy (Kongliga Ritarakademien). Founded in Stockholm in 1735 by the influential statesman and art connoisseur Count Carl Gustaf Tessin, the Academy was established within the Stockholm Palace. Its creation was a landmark event, aimed at formalizing art education in Sweden and raising the status of artists. Tessin, a great admirer of French culture, modeled the institution on the French Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture.

Scheffel was appointed as one of the first teachers at this prestigious institution. He shared teaching responsibilities with other notable artists of the day, including the French decorative painter Guillaume Thomas Raphaël Taraval, who played a crucial role in introducing the Rococo style to Sweden, particularly through his work in the Royal Palace. Olof Arenius, another respected Swedish painter, also served as an instructor. The architect Carl Håleman taught perspective and architectural drawing, rounding out the foundational curriculum.

As an instructor, Scheffel would have imparted his knowledge of drawing, composition, and painting techniques to a new generation of Swedish artists. His emphasis on careful observation and realistic depiction likely formed a core part of his teaching. The Academy provided a structured environment for students to learn from established masters, copy from casts of classical sculptures, and engage in life drawing. Scheffel's role in this educational framework was vital for nurturing local talent and professionalizing artistic practice in Sweden. One of his notable students was Per Krafft the Elder, who would himself become a distinguished portrait painter, continuing the tradition of skilled likeness and character study.

Artistic Style and Technique

Johann Henrik Scheffel's artistic style is best described as a blend of sober realism and a subtle psychological acuity, fitting for the intellectual climate of the Swedish Enlightenment. His works generally eschew the overt flamboyance and decorative excesses often associated with the high Rococo prevalent in other parts of Europe. Instead, Scheffel favored a more direct and unembellished approach, focusing intently on the sitter's face and conveying their personality through expression and posture.

His portraits are characterized by their fine and meticulous rendering of features. He paid close attention to the play of light and shadow on the face, modeling forms with a smooth, often polished finish. Clothing and accessories, while depicted with care and accuracy, rarely overwhelm the subject. Drapery is typically handled with a sense of solidity and texture, but without the elaborate flourishes seen in the work of some of his French contemporaries like Jean-Marc Nattier.

A hallmark of Scheffel's compositions is the use of relatively simple or neutral backgrounds. These often consist of dark, undefined spaces or plain architectural elements, which serve to throw the figure into greater prominence and direct the viewer's attention squarely onto the sitter. This contrasts with the more elaborate settings, complete with allegorical attributes or landscape vistas, sometimes employed by other portraitists. Scheffel's approach allowed the inherent dignity and intellectual weight of his subjects to speak for themselves.

His palette tended towards rich but restrained colors. He demonstrated a keen ability to capture the textures of different materials – the sheen of silk, the softness of velvet, the crispness of lace, or the metallic gleam of armor. While his work shows an awareness of international trends, it retains a distinct Northern European sensibility, prioritizing verisimilitude and a certain gravitas. This made his style particularly well-suited to portraying the scholars, scientists, and military men who were his frequent subjects.

Key Portrait Commissions and Notable Sitters

Johann Henrik Scheffel's oeuvre is distinguished by the prominence of the individuals he depicted. His portraits serve as a veritable who's who of the Swedish Enlightenment, capturing the likenesses of figures who made lasting contributions to science, academia, and public life.

Eric Benzelius the Younger (1675–1743)

One of Scheffel's significant portraits is that of Eric Benzelius the Younger, a highly influential theologian, librarian, and one of the founders of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences (Kungliga Vetenskapsakademien) in 1739. Scheffel’s depiction of Benzelius, often shown in dark clerical attire with a scholarly wig, captures the intellectual intensity and gravitas of this key Enlightenment figure. The portrait emphasizes Benzelius's thoughtful demeanor, befitting a man of letters and a pivotal figure in Sweden's scientific awakening. The simple background focuses attention on Benzelius's expressive face, conveying his wisdom and dedication.

Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778)

Perhaps one of Scheffel's most internationally recognized sitters was Carl Linnaeus, the father of modern taxonomy. Scheffel painted Linnaeus in 1755. This portrait, now housed at Linnaeus's Hammarby estate, depicts the renowned botanist in a formal yet approachable manner. Linnaeus is often shown holding a sprig of Linnaea borealis, the twinflower, a plant particularly dear to him and named in his honor by his friend Jan Frederik Gronovius. Scheffel’s portrayal captures Linnaeus's keen observational powers and his status as a leading scientific mind of his age. The painting conveys both the intellectual rigor and the quiet passion that drove Linnaeus's groundbreaking work.

Christopher Polhem (1661–1751)

Another luminary painted by Scheffel was Christopher Polhem, a brilliant inventor, industrialist, and scientist, often called the "father of Swedish mechanics." Scheffel’s portrait of Polhem, created in 1757 when Polhem was in his nineties, depicts the aged polymath with a sense of dignity and accumulated wisdom. Polhem's contributions to mining technology, clockmaking, and engineering were immense, and Scheffel’s portrayal reflects the respect and admiration he commanded. The painting likely aimed to immortalize a national hero of science and innovation.

Otto Reinhold Wrangel (1681–1747 or a later Wrangel)

Scheffel also painted military figures, such as his 1741 portrait of General Otto Reinhold Wrangel. This work, an oil on canvas measuring approximately 61 x 50 cm, shows Wrangel in a yellow uniform, his face rendered with Scheffel's characteristic attention to detail and personality. The depiction of military attire, including details like the wig and sash, is precise, yet the focus remains on Wrangel's commanding presence and individual character. Such portraits served to affirm the status and authority of military leaders in Swedish society. (Note: There were several prominent Otto Reinhold Wrangels; the specific individual would determine the exact context, but the style of portraiture for military figures remains consistent.)

Hedvig Charlotta Nordenflycht (1718–1763)

Scheffel also portrayed important female figures, including the influential poet and salonnière Hedvig Charlotta Nordenflycht. A leading voice of the Swedish Enlightenment and an early feminist thinker, Nordenflycht was a central figure in Stockholm's literary circles. Scheffel's portrait of her, now in the Uppsala University Art Collection, would have aimed to capture her intellectual prowess and literary sensibility. Such a commission underscores the growing recognition of women's contributions to cultural life during this period.

Gunilla Spole (1672–1751)

Among his other portraits is one of Gunilla Spole, the mother of Anders Celsius, the astronomer famous for the Celsius temperature scale. This connection to another major scientific family highlights Scheffel's role as the portraitist of choice for Sweden's intellectual elite. The painting would have served to commemorate a respected matriarch within a family of significant academic standing.

Kaptenen Peter Gotthard von Kochen (1684–1764)

An earlier work, dated 1728, depicts Captain Peter Gotthard von Kochen. This portrait, created relatively early in Scheffel's Swedish career, demonstrates his established skill in capturing a strong likeness and conveying the sitter's professional identity. The portrayal of military officers was a staple for portraitists, and Scheffel excelled in rendering the details of uniform and the bearing of his subjects.

These commissions, among many others, solidify Scheffel's reputation. His ability to create dignified and insightful likenesses made him a sought-after artist. His subjects were not just passive sitters; they were active participants in an era of profound change, and Scheffel's brush captured them at the height of their influence. His body of work offers an invaluable window into the personalities who drove Sweden's cultural and scientific advancement in the 18th century.

Contemporaries and Artistic Interactions

Johann Henrik Scheffel operated within a dynamic artistic community in 18th-century Sweden, interacting with a range of painters, patrons, and intellectuals. His position at the Royal Drawing Academy placed him at the heart of artistic education and discourse.

His colleagues at the Academy, Guillaume Taraval and Olof Arenius, were significant figures in their own right. Taraval, with his French training, was instrumental in introducing Rococo decorative schemes, particularly in the Royal Palace. Arenius was a respected Swedish painter known for his portraits and altarpieces. Their collaboration in teaching suggests a shared mission to elevate Swedish art, even if their individual styles differed. The architect Carl Håleman, also teaching at the Academy, contributed to the interdisciplinary environment.

Beyond the Academy, Scheffel's contemporaries included Gustaf Lundberg, whose delicate pastel portraits offered a softer, more overtly Rococo alternative to Scheffel's oil paintings. While their styles differed, they catered to a similar clientele of aristocracy and wealthy burghers. Johan Pasch, brother of Lorens Pasch the Elder, was known for his decorative paintings and historical subjects. The Pasch family, including Lorens Pasch the Elder, his son Lorens Pasch the Younger, and daughter Ulrika Pasch, formed a veritable dynasty of painters, contributing significantly to Swedish portraiture and genre scenes throughout the 18th century.

Scheffel would also have been aware of the work of slightly earlier Swedish portraitists like David Richter the Elder and Younger, and Georg Engelhard Schröder, whose styles formed part of the artistic landscape he entered. The influence of internationally renowned Swedish artists working abroad, such as Michael Dahl in England, also permeated the artistic consciousness of the time.

Later in Scheffel's career, younger talents like Alexander Roslin and Carl Gustaf Pilo emerged. Roslin, in particular, achieved immense international success, becoming a favored portraitist in Paris and other European courts. While Roslin's style was generally more flamboyant and aligned with French Rococo elegance, the foundational emphasis on likeness and character, evident in Scheffel's work, remained a constant in Swedish portraiture.

Scheffel's student, Per Krafft the Elder, carried forward a tradition of solid, insightful portraiture, later becoming a professor at the Academy himself. This master-pupil relationship demonstrates Scheffel's direct influence on the next generation. The intellectual circles in which Scheffel moved, exemplified by sitters like Linnaeus and Benzelius, also fostered a climate of cross-disciplinary exchange, where art and science were not seen as entirely separate realms. Patrons like Count Tessin were pivotal in connecting artists with opportunities and promoting a cohesive cultural vision. Scheffel's interactions within this network were crucial to his success and his lasting impact on Swedish art.

Legacy and Collections

Johann Henrik Scheffel's legacy is primarily that of a skilled and insightful portraitist who meticulously documented the key figures of the Swedish Age of Liberty and Enlightenment. His work provides an invaluable historical and cultural record, offering visual testimony to the intellectual ferment and societal shifts of 18th-century Sweden. He captured not just the likenesses but also the character and dignity of his sitters, contributing to a national narrative of progress and intellectual achievement.

His role as an early instructor at the Royal Drawing Academy was also crucial. By helping to lay the foundations for formal art education in Sweden, he contributed to the development of future generations of artists, fostering a professional standard and a distinctly Swedish artistic tradition. His student, Per Krafft the Elder, and subsequently Krafft's own son, Per Krafft the Younger, continued this lineage of skilled portraiture.

Scheffel's paintings are preserved in several important Swedish collections. The Uppsala University Art Collection holds a number of his works, including the portrait of Hedvig Charlotta Nordenflycht. Given Uppsala's status as a major center of learning and the university's connection to many of his sitters (like Linnaeus and Benzelius), this is a fitting repository. Linnaeus's former home and museum at Hammarby preserves Scheffel's portrait of the great botanist, offering visitors a direct encounter with the man in his historical environment.

Other works by Scheffel can be found in the Swedish National Museum in Stockholm, which houses the foremost collection of Swedish art, as well as in various regional museums, private collections, and institutions associated with the families or fields of his sitters. For instance, portraits of military figures might be found in collections related to military history, and likenesses of nobles within ancestral family estates.

While Scheffel may not have achieved the widespread international fame of some of his slightly later Swedish contemporaries like Alexander Roslin, his importance within the Swedish context is undeniable. His style, less flamboyant than the high Rococo, possessed a sobriety and directness that resonated with the intellectual and often pragmatic spirit of the Swedish Enlightenment. His portraits remain significant artistic achievements, valued for their technical skill, their psychological depth, and their historical importance as windows into a pivotal era of Swedish culture.

Conclusion: An Enduring Chronicler of an Enlightened Age

Johann Henrik Scheffel carved out a distinguished career as a premier portrait painter in 18th-century Sweden. Arriving with a robust Northern European artistic education, he adapted his skills to the specific cultural climate of the Swedish Age of Liberty, an era ripe with intellectual curiosity and a desire for self-representation among its leading citizens. His portraits of scientists like Carl Linnaeus and Christopher Polhem, academics like Eric Benzelius, writers like Hedvig Charlotta Nordenflycht, and military figures like Otto Reinhold Wrangel, are more than mere likenesses; they are documents of an age, imbued with the character and gravitas of individuals who shaped their nation's destiny.

Scheffel's style, marked by its meticulous realism, restrained palette, and focus on the sitter's individuality, set him apart. He largely eschewed overt Rococo embellishments, preferring a clarity and psychological insight that resonated with the Enlightenment ethos. His significant role as an early educator at the Royal Drawing Academy further cemented his influence, helping to nurture a new generation of Swedish artists and professionalize artistic practice in the country.

Through his extensive body of work, primarily housed today in Swedish national and university collections, Johann Henrik Scheffel remains a vital link to the past. His canvases allow us to meet the faces of the Swedish Enlightenment, offering a tangible connection to the personalities who drove innovation and cultural development. As a faithful chronicler and a skilled artist, Scheffel's contribution to Swedish art history is both substantial and enduring.