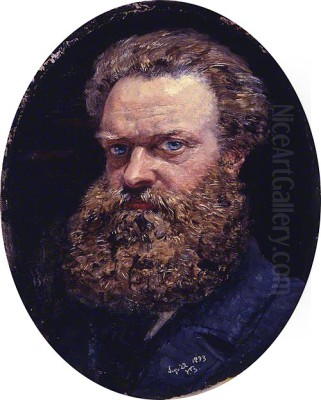

John Brett (1831-1902) stands as a significant, albeit sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of nineteenth-century British art. Primarily associated with the Pre-Raphaelite movement, Brett dedicated his career to the meticulous and scientifically informed depiction of the natural world. His canvases, renowned for their extraordinary detail and vibrant colour, capture landscapes and seascapes with an intensity that reflects both artistic passion and a deep engagement with the scientific understanding of his time. From the rugged Alps to the dramatic coastlines of Britain and the Mediterranean, Brett sought truth in nature, leaving behind a legacy of visually stunning and intellectually engaging works.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

John Brett was born on December 8, 1831, in Bletchingley, Surrey, a village nestled near Reigate. His father was a veteran army officer, and his mother was Ann Philips. While a military career was initially considered for the young Brett, his inclinations steered him firmly towards the arts. His formal artistic training began around 1851 when he sought instruction from established figures in the London art scene.

He studied under James Duffield Harding (1798-1863), a respected landscape painter and lithographer known for his picturesque style and instructional manuals. Brett also learned from Richard Redgrave (1804-1888), another prominent Victorian artist and arts administrator, who was associated with genre scenes and later, landscape painting. These early mentors provided Brett with a solid foundation in technique and composition.

In 1853, Brett took a significant step by enrolling in the prestigious Royal Academy Schools in London. This period proved crucial for shaping his artistic direction. It was during this time, facilitated by an introduction from the poet Coventry Patmore (1823-1896), that Brett encountered the influential art critic John Ruskin (1819-1900) and the leading Pre-Raphaelite painter William Holman Hunt (1827-1910). These encounters would profoundly impact his artistic philosophy.

The Pre-Raphaelite Connection

Although John Brett never formally became a member of the original Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood – founded in 1848 by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais (1829-1896), and Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882) – his work became deeply aligned with their core tenets, particularly as championed by John Ruskin. Ruskin's call for artists to "go to Nature in all singleness of heart... rejecting nothing, selecting nothing, and scorning nothing" resonated strongly with Brett.

Inspired specifically by Hunt's concept of the "scientific landscape," which aimed for geological and botanical accuracy alongside aesthetic beauty, Brett embraced a method rooted in intense observation and meticulous rendering. He sought to capture the intricate details of the natural world with almost photographic precision, believing this fidelity revealed a deeper truth and beauty inherent in creation.

His commitment to these principles led him to travel. Following Ruskin's advice and inspired by the Pre-Raphaelite emphasis on direct experience, Brett journeyed to Switzerland in 1856. There, amidst the grandeur of the Alps, he undertook rigorous plein air studies, striving to capture the complex geological formations and atmospheric effects with unparalleled accuracy. This period saw him engage with the kind of landscapes also being tackled by contemporaries like John William Inchbold (1830-1888), another artist heavily influenced by Ruskin's ideas on landscape painting.

Brett's association with the Pre-Raphaelite circle, therefore, was one of shared ideals rather than formal membership. He became one of the foremost exponents of the Pre-Raphaelite landscape style, pushing the boundaries of detailed realism in his depictions of nature, often imbuing them with the moral seriousness favoured by Ruskin and Hunt.

Breakthrough and Key Works: The Stonebreaker and Val d'Aosta

Brett's dedication to the Pre-Raphaelite style yielded its first major public success with The Stonebreaker, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1858. This painting depicts a young boy diligently breaking stones for road mending, set against a brilliantly lit, minutely detailed landscape background in Surrey. The work is a prime example of Pre-Raphaelite principles: intense detail, vibrant colour, and a contemporary subject imbued with social commentary.

The painting received considerable attention, most notably high praise from John Ruskin. Ruskin admired the painting's geological accuracy, the rendering of light, and its poignant portrayal of child labour, seeing it as a powerful moral statement. He declared it "simply the most perfect piece of painting with respect to touch" in the exhibition that year. This endorsement significantly boosted Brett's reputation and solidified his position within the Pre-Raphaelite sphere.

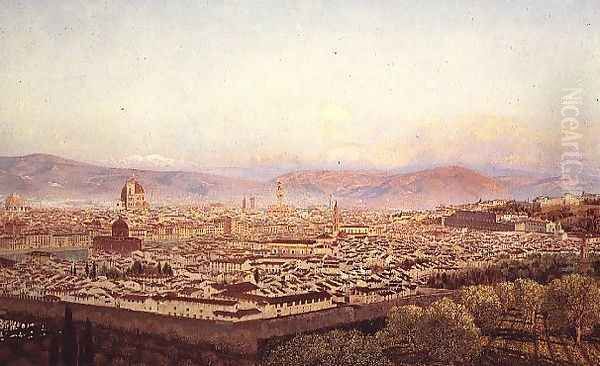

Also stemming from his travels, and exhibited the following year (1859), was Val d'Aosta. This panoramic view of the Italian Alps is arguably one of Brett's masterpieces and a quintessential example of the scientific Pre-Raphaelite landscape. Painted with astonishing detail, every rock, flower, tree, and distant peak is rendered with crystalline clarity under a bright, even light. The painting showcases Brett's profound understanding of geology and botany, acquired through direct observation and study.

Val d'Aosta was commissioned by Ruskin, although the critic later expressed some reservations, finding it perhaps lacking in compositional artistry despite its incredible fidelity. Nevertheless, the painting remains a landmark work, demonstrating Brett's technical virtuosity and his commitment to capturing the sublime power and intricate detail of the Alpine environment. An earlier work, The Glacier of Rosenlaui (1856), painted during his Swiss trip, similarly displayed this commitment to capturing glacial landscapes with scientific precision.

Master of Landscape and Geology

Following the success of The Stonebreaker and Val d'Aosta, Brett firmly established himself as a leading landscape painter. His approach remained rooted in meticulous observation and scientific accuracy. He possessed a keen interest in geology, meteorology, and botany, knowledge which informed the detailed rendering of rock strata, cloud formations, and plant life in his paintings. This scientific underpinning distinguished his work from the more atmospheric or romantic approaches of earlier landscape masters like J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851) or John Constable (1776-1837).

Brett continued to travel in search of subjects, visiting Italy again in the early 1860s. His dedication to plein air painting – working directly outdoors – was central to his practice. He often employed a technique of painting in oils on a canvas prepared with a wet white ground. This method enhanced the luminosity and brilliance of his colours, contributing to the characteristic high-keyed palette and sharp focus found in his best works.

His landscapes from this period often feature expansive views, meticulous foreground detail, and a sense of deep space under clear, bright skies. While sometimes criticized by contemporaries for a perceived lack of emotional depth or painterly freedom compared to artists like Constable, Brett's work offered a different kind of engagement with nature – one grounded in empirical observation and a sense of wonder at the complexity of the physical world. His detailed approach found parallels in the work of other Victorian landscape artists who emphasized detail, such as Myles Birket Foster (1825-1899), though Brett's scientific rigour remained distinctive.

The Lure of the Sea

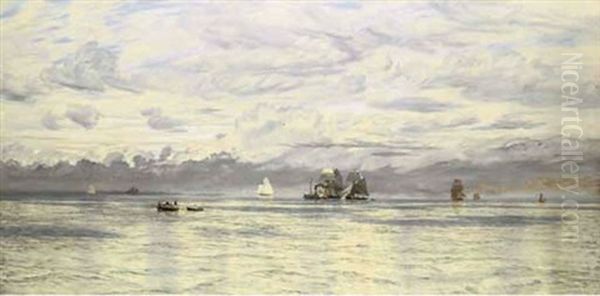

From the mid-1860s onwards, John Brett's artistic focus began to shift increasingly towards coastal scenes and marine subjects. This transition was fuelled by his personal passion for sailing. He was an enthusiastic yachtsman, owning a 210-ton schooner named 'Viking', which he used extensively for sketching expeditions around the British Isles and across the Mediterranean. His maritime experiences provided him with intimate knowledge of the sea, ships, and coastal topography.

During the 1870s and 1880s, Brett spent considerable time exploring and painting the dramatic coastlines of Cornwall, the Channel Islands, Wales, and the Mediterranean. He even rented Newport Castle in Pembrokeshire for several summers, using it as a base for his family and his artistic excursions along the Welsh coast. This period produced many of his most celebrated works.

Paintings such as Britannia's Realm (1880), a sweeping panorama of the English Channel teeming with shipping under a vast sky, and The Land's End, Cornwall (1880), demonstrate his ability to capture the grandeur and specific character of Britain's maritime environment. His seascapes are noted for their accurate depiction of wave patterns, reflections, atmospheric effects, and the geological features of cliffs and shorelines. Works like The Black East Wind (1880) capture the harsher aspects of the sea.

His later marine paintings, such as Pearly Summer (1891) and Rise of Tides - Coast of Scilly (1885), often display a brighter palette and perhaps a slightly looser handling than his earlier Alpine works, but the commitment to detailed observation and the effects of light on water remains paramount. He captured the brilliance of sunlight on calm seas and the dramatic interplay of light and shadow on coastal rock formations with exceptional skill, rivaling dedicated marine specialists like Clarkson Stanfield (1793-1867) in accuracy, though with his distinct Pre-Raphaelite clarity.

Scientific Pursuits: Astronomy

Beyond geology and botany, Brett nurtured a lifelong passion for astronomy. This interest in the cosmos mirrored his dedication to precise observation in his terrestrial landscapes and seascapes. He didn't just paint the sky; he studied it with scientific rigour. He acquired his own telescope and became a knowledgeable amateur astronomer.

His dedication to the science was formally recognized in 1871 when he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society (FRAS). This honour highlights the seriousness of his astronomical pursuits and underscores the unique intersection of art and science in his life and work. While his paintings don't typically feature overt astronomical events, the accuracy with which he depicted skies, cloud formations, and atmospheric light effects undoubtedly benefited from his scientific understanding. This scientific inclination set him apart from many contemporaries, including those within the broader Pre-Raphaelite circle like Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898), whose work moved towards symbolism and myth rather than scientific realism.

Later Career and Style Evolution

John Brett remained a prolific artist throughout his later career, exhibiting regularly at the Royal Academy and other venues. He continued to produce highly detailed coastal and marine paintings, which found a ready market among Victorian collectors who appreciated their precision and topographical accuracy. His distinctive style, characterized by sharp focus, bright colours, and meticulous detail, remained largely consistent.

However, critical opinion sometimes shifted. While his technical skill was rarely questioned, some later critics found his relentless detail could lead to a certain hardness or lack of atmosphere, occasionally describing his work as overly 'fussy' or 'photographic'. This criticism reflected changing tastes in the art world, which was moving towards Impressionism and broader, more suggestive styles. Brett, however, remained largely committed to his established Pre-Raphaelite principles of truth to nature through detailed representation.

Beyond his painting, Brett was also involved in the broader art community. He was one of the founder members of the Art Workers' Guild in 1884. This organization, established by figures associated with the Arts and Crafts movement like William Morris (1834-1896) and Walter Crane (1845-1915), aimed to break down barriers between fine art and decorative crafts, promoting the value of skilled workmanship across different artistic disciplines. Brett's involvement reflects his own meticulous craftsmanship and perhaps a shared belief in the integrity of well-made objects, whether paintings or other forms of art. His contemporaries at the Royal Academy, like Frederic Leighton (1830-1896), represented a more classical establishment, highlighting the diverse currents within Victorian art.

Legacy and Reappraisal

John Brett passed away in London on January 7, 1902, at his home in Putney, aged 70. He left behind a substantial body of work primarily focused on landscape and marine subjects, executed with a distinctive, highly detailed realism rooted in Pre-Raphaelite ideals and scientific observation. For much of the 20th century, his reputation, like that of many Victorian artists, suffered a decline as modernist aesthetics took hold.

However, the late 20th and early 21st centuries have seen a significant reappraisal of Victorian art, and John Brett's work has enjoyed renewed interest and appreciation. His technical brilliance, his unique synthesis of art and science, and the sheer visual impact of his detailed canvases are increasingly recognized. His paintings offer valuable insights into the Victorian fascination with science, nature, and empirical observation.

A major exhibition titled "John Brett - a Pre-Raphaelite on the Shores of Wales," held at the National Museum Wales in Cardiff in 2001, played a key role in bringing his work to a wider audience and reassessing his contribution, particularly his stunning depictions of the Welsh coastline. Accompanying publications further explored his life and art.

Today, John Brett is acknowledged as a master of detailed landscape and marine painting. His works, held in major public collections in the UK and beyond, stand as testaments to a unique artistic vision that sought to capture the intricate beauty and underlying order of the natural world with unparalleled fidelity. He remains a key figure for understanding the landscape strand of the Pre-Raphaelite movement and the complex relationship between art and science in the 19th century. His influence can be seen in subsequent artists who valued precision and close observation of nature.

Conclusion

John Brett occupies a unique niche in the history of British art. As an artist deeply influenced by Pre-Raphaelite ideals and the scientific spirit of the Victorian age, he forged a distinctive path focused on the meticulous, almost forensic, observation of nature. His landscapes of the Alps and his later, numerous depictions of Britain's coasts and seas are remarkable for their clarity, detail, and vibrant colour. While not a formal member of the Brotherhood, he was arguably the most dedicated and accomplished exponent of the Pre-Raphaelite landscape. His life, marked by a passion for sailing and astronomy alongside his art, reveals a man fascinated by the workings of the natural world. Though subject to the fluctuations of taste, John Brett's legacy endures through paintings that continue to astonish viewers with their technical mastery and intense vision of reality.