John Brett stands as a significant figure in the landscape of nineteenth-century British art. Born on December 8, 1831, in Bletchingley, Surrey, and passing away on January 7, 1902, Brett carved a unique niche for himself, primarily associated with the Pre-Raphaelite movement, though never a formal member of the Brotherhood itself. He is celebrated for his landscape paintings, which are characterized by an extraordinary level of detail, scientific accuracy, and a vibrant, luminous quality, capturing the natural world with an intensity that remains compelling. His life and work offer a fascinating window into the artistic and intellectual currents of the Victorian era, particularly the intersection of art, science, and the influential ideals of the Pre-Raphaelites.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

John Brett's journey into the art world began in a family environment that was not entirely removed from creative pursuits. His father was a veteran of the army, and his sister, Rosa Brett, would also become a recognized artist, sharing perhaps a familial inclination towards visual expression, though her focus often leaned towards oil and watercolour studies distinct from John's grander landscapes. The family later moved to the nearby town of Reigate.

Around the age of twenty, in 1851, Brett commenced formal art training. He sought instruction from established figures like the landscape painter and drawing master James Duffield Harding, known for his picturesque style and instructional manuals. He also studied under Richard Redgrave, a versatile artist and influential art administrator associated with the Government School of Design. This initial training provided Brett with a foundation in technique and composition.

A pivotal moment came in 1853 when Brett enrolled in the prestigious Royal Academy Schools in London. This institution was the epicentre of the British art establishment, yet it was also a place where new ideas were fermenting. It was during this period that Brett encountered the burgeoning influence of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the powerful art criticism of John Ruskin, forces that would profoundly shape his artistic direction.

The Influence of Ruskin and Pre-Raphaelitism

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB), officially formed in 1848 by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, sought to revolutionize British art. They rejected the perceived academicism and mannered style derived from followers of Raphael, advocating instead for a return to the perceived honesty, intense detail, and bright colour found in early Italian Renaissance art (before Raphael). Their motto was "truth to nature," involving meticulous observation and depiction of the natural world, often imbued with complex symbolism or moral narratives.

While not one of the original seven members, John Brett became deeply aligned with the Pre-Raphaelite ethos, particularly its application to landscape painting. He was significantly influenced by the writings and pronouncements of John Ruskin, the era's pre-eminent art critic. Ruskin championed the PRB and urged artists, particularly landscape painters, to render nature with utmost fidelity, paying close attention to geological formations, botanical details, and atmospheric effects. Ruskin saw this detailed naturalism as a moral imperative, a way of appreciating God's creation.

Brett absorbed these ideas keenly. He was directly encouraged by William Holman Hunt, one of the PRB founders known for his own intensely detailed and symbolic works like The Hireling Shepherd. Furthermore, Brett developed a connection with the landscape painter John William Inchbold. Inchbold, also admired by Ruskin, was pioneering a form of highly detailed, almost scientifically observed landscape painting. Brett met Inchbold through the poet Coventry Patmore, indicating his immersion in circles where Pre-Raphaelite ideas were actively discussed and practiced. Brett's commitment to rendering landscape with scientific precision became a hallmark of his early and most celebrated work.

Breakthrough Works: The Stonebreaker and Val d'Aosta

The year 1858 marked a significant breakthrough for John Brett with the exhibition of The Stonebreaker at the Royal Academy. This painting depicts a young boy diligently breaking stones for road mending, set against a meticulously rendered backdrop of Box Hill in Surrey. The landscape is bathed in bright, clear sunlight, with every leaf, stone, and blade of grass depicted with astonishing precision, fulfilling Ruskin's call for detailed observation.

Beyond its technical brilliance, The Stonebreaker carried a strong social and moral message, typical of some Pre-Raphaelite works. It highlighted the harsh reality of child labour, contrasting the beauty and indifference of nature with the toil of the young worker. The painting garnered considerable attention, most importantly receiving high praise from John Ruskin himself. Ruskin admired its truthfulness and detailed execution, seeing it as a prime example of the principles he advocated.

So impressed was Ruskin that he offered practical support. Believing Brett capable of producing a landscape masterpiece if given the right subject, Ruskin encouraged and likely helped fund Brett's journey to the Italian Alps in the summer of 1858. The specific goal was to paint in the Val d'Aosta region, following Ruskin's instructions to capture the geological and botanical specifics of the Alpine landscape with the same fidelity he had shown in The Stonebreaker.

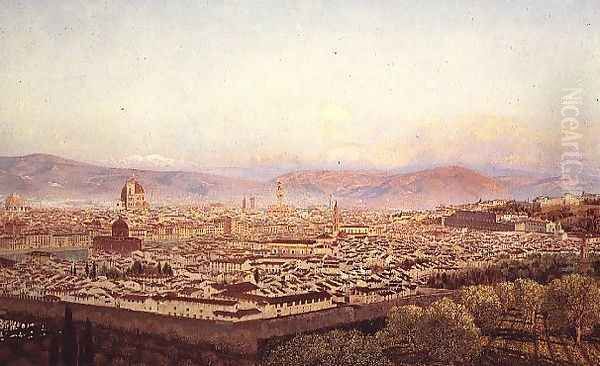

The result was Val d'Aosta, exhibited in 1859. This panoramic view, looking down the valley towards the Alps, is another tour de force of detailed observation. Brett painstakingly rendered the complex rock strata, the distant snow-capped peaks, the lush vegetation of the valley floor, and the intricate details of the foreground. Ruskin again lauded the work for its scientific accuracy and truth to nature, even purchasing the painting, although he also offered some criticism regarding its composition. These two paintings firmly established Brett's reputation as a leading exponent of the Pre-Raphaelite landscape style.

Scientific Observation and Landscape

John Brett's approach to landscape painting in his prime was deeply rooted in scientific observation. He wasn't merely capturing a picturesque view; he was documenting the natural world with an almost geological or botanical rigour. This aligned perfectly with the Victorian era's burgeoning interest in science and the belief that close study of nature revealed underlying truths, whether scientific or divine.

His paintings from the late 1850s and 1860s, including works like Glacier of Rosenlaui (1856) painted during an earlier trip to Switzerland, demonstrate this commitment. He meticulously studied rock formations, the structure of glaciers, the specific types of plants found in a location, and the effects of light and atmosphere. He often worked outdoors, making detailed sketches and colour notes directly from nature, a practice advocated by Ruskin and central to the Pre-Raphaelite method.

This scientific approach extended beyond geology and botany. Brett was also a keen amateur astronomer. His interest in the skies, evident from childhood, led him to become a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1871. While not always explicit in his landscapes, this understanding of light, atmosphere, and celestial phenomena likely informed his sensitive rendering of skies and weather conditions, which are often notable features in his work. His paintings aimed for a clarity and luminosity that suggested careful observation of natural light effects.

Travels and Expanding Horizons

Following the success of Val d'Aosta, Brett continued to travel in search of subjects that allowed for his detailed approach. The 1860s saw him journeying to the Mediterranean. His painting Massa, Bay of Naples (1863-64) captures the brilliant light and distinctive coastline of southern Italy, again rendered with sharp focus and meticulous attention to detail, though perhaps with a slightly broader handling than his Alpine work.

However, much of Brett's subsequent career focused on the varied coastlines of Britain. He developed a particular affinity for the dramatic cliffs and seascapes of Cornwall, the Channel Islands (Guernsey and Sark), the Isle of Wight, and Wales. These locations offered rugged geological features, diverse coastal flora, and challenging maritime weather conditions that suited his observational style.

His method often involved extensive sketching trips. In the 1880s, he took the significant step of renting Newport Castle in Pembrokeshire, Wales. This provided him with a base from which to explore and paint the coastlines of both South and North Wales extensively. He also took up photography during this period, likely using it as an additional tool for recording landscape details, although painting remained his primary medium. These travels provided a continuous stream of subjects for his brush.

Mastery of the Coastline

From the 1870s onwards, coastal and marine subjects increasingly dominated Brett's output. He acquired a 210-ton schooner, the Viking, which enabled him to explore the British coastline extensively and observe the sea and sky in various conditions from an offshore perspective. This maritime experience infused his later work with a deep understanding of wave patterns, cloud formations, and the specific light found at sea.

His coastal scenes often feature panoramic views, emphasizing the vastness of the sea and sky, punctuated by detailed renderings of cliffs, beaches, and rock formations in the foreground or middle distance. Works like Britannia's Realm (1880), depicting a wide expanse of sunlit sea off the Welsh coast, are considered among his most successful later paintings. It captures the shimmering surface of the water and the atmospheric distance with considerable skill, showcasing his accumulated knowledge of marine effects.

While these later coastal scenes maintained a high degree of accuracy and clarity, some critics felt they became somewhat formulaic compared to the intense, almost revelatory detail of his earlier Pre-Raphaelite masterpieces. The compositions could be repetitive, often employing a high horizon line and a wide, panoramic format. Nevertheless, they were popular with the public and consistently exhibited at the Royal Academy and other venues, cementing his reputation as one of Britain's foremost marine painters of the period.

Artistic Style and Technique

John Brett's artistic style is most strongly defined by its adherence to Pre-Raphaelite principles, particularly in the first decade of his mature career. Key characteristics include:

Meticulous Detail: An almost microscopic attention to the rendering of natural forms – rocks, plants, water surfaces, clouds.

Bright Colour and Luminosity: Use of a high-keyed palette and clear, often bright, even lighting to enhance the sense of realism and clarity. He achieved this through painting on a white ground, a technique favoured by the PRB.

Sharp Focus: A tendency towards sharp focus throughout the picture plane, minimizing atmospheric perspective in favour of revealing detail even in distant objects.

Scientific Accuracy: A commitment to depicting geological strata, botanical species, and weather phenomena with verifiable accuracy.

Composition: Often favouring panoramic views, especially in his later coastal scenes, sometimes criticized for lacking compositional variety.

His technique involved careful preliminary drawing and extensive sketching directly from nature. He applied paint in thin layers over a smooth white ground to achieve luminosity. While highly effective in rendering detail and light, this meticulous, labour-intensive approach sometimes led to criticism that his work was overly photographic, unemotional, or "mechanical," lacking the broader, more suggestive handling favoured by other landscape traditions, such as the Barbizon School in France or the later Impressionists. Artists like J.M.W. Turner, whom Ruskin also championed, achieved atmospheric effects through much looser brushwork, presenting a contrast to Brett's precise style.

Beyond Painting: Astronomy and the Art Workers' Guild

John Brett's interests extended beyond the canvas. His lifelong passion for astronomy was a serious pursuit. Becoming a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1871 was a significant recognition of his knowledge and observational skills in this field. This scientific inclination undoubtedly informed the precision and observational basis of his art, reflecting a Victorian mindset where art and science were not necessarily seen as separate spheres but could mutually enrich each other.

Furthermore, Brett was involved in the burgeoning Arts and Crafts movement. In 1890, he was a founding member and served as Master of the Art Workers' Guild. This organization brought together architects, painters, sculptors, and craftspeople who shared ideals about the importance of craftsmanship, the integration of the arts, and often, a reaction against industrial mass production. Its members included prominent figures like Walter Crane and William Morris (though Morris's relationship with the Guild was complex). Brett's involvement suggests a commitment to broader artistic principles and fellowship among artists and artisans, moving beyond the confines of easel painting.

Contemporaries and Connections

John Brett operated within a rich and dynamic artistic milieu. His closest ties were naturally with the Pre-Raphaelite circle. He admired and was encouraged by William Holman Hunt. He learned from the landscape techniques of John William Inchbold. His work was exhibited alongside that of the original PRB members John Everett Millais and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, as well as key associates like Ford Madox Brown, whose own detailed realism and social commentary resonated with Brett's Stonebreaker.

He would have known many other artists through the Royal Academy Schools and exhibitions. His detailed landscape approach finds parallels in the work of contemporaries like George Price Boyce, another watercolourist and painter known for his meticulous renderings of landscapes and architecture, also admired by Ruskin. The influence of John Ruskin was, of course, paramount, connecting Brett to a wider network of artists responsive to his ideas.

Later Pre-Raphaelite figures like Edward Burne-Jones, though focused more on imaginative and medieval subjects, shared the emphasis on careful drawing and decorative richness. Brett's mentors, James Duffield Harding and Richard Redgrave, represent the more established landscape and academic traditions against which the PRB initially reacted, yet they provided Brett's foundational training. His sister, Rosa Brett, and brother, Arthur Brett (who sketched John's portrait), formed part of his immediate artistic family. He would also have been aware of other prominent Victorian landscape painters, such as Alfred William Hunt, who combined detailed observation with atmospheric effects in watercolour. Brett's career unfolded alongside these diverse talents, reflecting the varied landscape of Victorian art.

Later Career and Legacy

In the later decades of his career, while Brett remained a regular exhibitor and a respected figure, particularly as a marine painter, the intense critical acclaim that greeted his early Pre-Raphaelite works somewhat diminished. Artistic tastes began to shift. The rise of Aestheticism, and later Impressionism, favoured different approaches to landscape, emphasizing mood, suggestion, and the fleeting effects of light over meticulous documentation. Brett's unwavering commitment to detailed realism perhaps began to seem less innovative to some critics.

His later coastal scenes, though technically proficient and popular, were sometimes seen as repetitive. The very precision that had once been hailed as revolutionary was occasionally criticized as lacking painterly freedom or emotional depth. Consequently, after his death in 1902, Brett's reputation entered a period of relative decline, overshadowed by the more famous original Pre-Raphaelites and by subsequent art movements.

However, the late 20th and early 21st centuries witnessed a significant reassessment of Victorian art, including the contributions of John Brett. Scholars and curators began to look afresh at his remarkable technical skill, his unique synthesis of art and science, and the sheer beauty and intensity of his best work. Major exhibitions, such as the one held at the National Museum Wales in Cardiff in 2001, titled "Brett: A Pre-Raphaelite on the Shores of Wales," brought his work back into the public eye and highlighted his specific connection to Welsh scenery. Today, his paintings are held in major public collections in the UK and internationally, recognized for their unique place within the Pre-Raphaelite landscape tradition.

Conclusion

John Edward Brett remains a compelling figure in British art history. As a landscape painter deeply influenced by John Ruskin and the Pre-Raphaelite movement, he pursued a vision of "truth to nature" with extraordinary dedication and skill. His early masterpieces, The Stonebreaker and Val d'Aosta, stand as iconic examples of Pre-Raphaelite landscape painting, fusing meticulous detail, scientific observation, and sometimes social commentary. His later career, dominated by luminous and expansive coastal scenes, solidified his reputation as a master of marine painting.

Though his style sometimes courted criticism for its photographic precision, Brett's work embodies a fascinating aspect of the Victorian era – its intense engagement with the natural world, its faith in observation, and its attempts to reconcile art with science. His legacy lies in the stunning clarity and detail of his paintings, which continue to offer a powerful and minutely observed vision of the landscapes and seascapes of Britain and Europe in the 19th century. He was more than just a follower; he was an artist who took the principles of Pre-Raphaelitism and applied them to the natural world with a unique and enduring intensity.