John Mulcaster Carrick (1833-1896) stands as a notable, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of nineteenth-century British art. A painter, and reportedly an engraver and illustrator, Carrick navigated the dynamic artistic currents of his time, most significantly aligning himself with the principles of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. His legacy is primarily built upon his evocative landscapes, particularly his detailed and atmospheric coastal scenes, as well as his forays into historical and literary subjects. Born in an era of profound industrial change and romantic yearning for the past, Carrick’s art reflects a deep engagement with the natural world and the enduring power of narrative.

Early Life and Formative Context

John Mulcaster Carrick was born in Carlisle, Cumberland, in 1833. This region, known for its picturesque landscapes bordering Scotland, may well have provided early inspiration for the young artist’s affinity for nature. His family background was distinguished; he was a descendant of Sir Richard Mulcaster (c. 1531 – 1611), an influential Elizabethan scholar and headmaster of schools like St Paul's and Merchant Taylors', renowned for his progressive views on education and his contributions to the English language. This lineage suggests an environment where intellectual and cultural pursuits were valued, potentially fostering Carrick's artistic inclinations.

The mid-nineteenth century in Britain was a period of artistic ferment. The Royal Academy, while dominant, faced challenges from emerging movements. Romanticism, with its emphasis on emotion and the sublime power of nature, as championed by artists like J.M.W. Turner and John Constable, had laid a crucial foundation for landscape painting. By the time Carrick was embarking on his artistic journey, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, formed in 1848 by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, was advocating for a radical return to the detailed realism and vibrant colour found in art before Raphael. Their motto, "truth to nature," resonated with a public increasingly appreciative of scientific observation and detailed depiction.

The Pre-Raphaelite Influence and Carrick's Stylistic Approach

John Mulcaster Carrick is firmly identified with the Pre-Raphaelite movement, or at least its broader circle of influence. This artistic school, in its initial phase, championed meticulous detail, a bright palette achieved by painting on a wet white ground, and often, subjects drawn from literature, religion, or contemporary social issues, imbued with symbolic meaning. Carrick’s work, particularly his landscapes, demonstrates a keen adherence to the Pre-Raphaelite tenet of observing and recording nature with utmost fidelity.

His paintings often feature an intense focus on botanical detail, geological formations, and the transient effects of light and atmosphere. This dedication to capturing the specifics of a scene, rather than a generalized or idealized view, aligns perfectly with the Pre-Raphaelite ethos promoted by influential critics like John Ruskin. Ruskin urged artists to "go to Nature in all singleness of heart... rejecting nothing, selecting nothing, and scorning nothing." Carrick’s detailed renderings of coastal scenery, with their carefully delineated rocks, foliage, and water, suggest he took this advice to heart. His landscapes are not mere topographical records but are imbued with a palpable sense of place and a quiet, observant poetry.

While the core Brotherhood had somewhat dispersed by the late 1850s, their influence persisted and spread, impacting a wider generation of artists, including Carrick. Figures like Ford Madox Brown, though never an official member, was closely associated with their ideals. A second wave of artists, including Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris, carried Pre-Raphaelite sensibilities into new realms of decorative art and mythic storytelling. Carrick’s engagement seems to be more with the landscape aspect, akin to artists like John Brett, who was particularly known for his incredibly detailed coastal scenes and landscapes, directly influenced by Ruskin and Pre-Raphaelite principles.

Coastal Scenes and the Lure of the Sea

A significant portion of John Mulcaster Carrick's oeuvre is dedicated to coastal and marine subjects. The Victorian era saw a burgeoning fascination with the seaside, driven by improved transportation, the rise of coastal resorts, and a romantic appreciation for the untamed beauty of Britain's shores. Carrick excelled in capturing the varied moods of the coast, from tranquil sunlit coves to more dramatic clifftop vistas.

His painting Enys Dodnan, Cornwall (the title likely refers to a rock formation near Land's End, possibly Enys Dodman) exemplifies his skill in this genre. One can anticipate in such a work the careful articulation of rock strata, the play of light on water, and the meticulous rendering of coastal flora, all hallmarks of the Pre-Raphaelite landscape. Cornwall, with its rugged coastline and unique light, was a popular destination for artists in the nineteenth century, attracting painters like Walter Langley and Stanhope Forbes who would later form the Newlyn School, though Carrick's approach would have been distinct from their later, more impressionistic and socially-focused realism.

Another notable work, A coastal view with figures collecting gulls' eggs on the clifftops, highlights his ability to integrate human activity within the grandeur of nature. The figures, while small, add a narrative element and a sense of scale, a common feature in Victorian landscape painting. This painting, like others, would have demanded close observation and a patient, detailed technique to capture the textures of the cliffs, the sea, and the distant horizon. The practice of egg collecting, while viewed differently today, was a traditional coastal activity, and its depiction adds a layer of social observation to the scene.

Journeys and Landscapes Beyond Britain: Villefranche-sur-Mer and Monaco

Carrick's artistic gaze was not limited to the British Isles. He also travelled to the Continent, capturing the distinct light and scenery of the Mediterranean. His View of Villefranche-sur-Mer is a testament to this. Villefranche, on the French Riviera, with its deep bay and picturesque old town, offered a different palette and atmosphere compared to the often more muted tones of the British coast. Such works allowed artists to explore brighter colours and sharper contrasts, appealing to a clientele increasingly interested in travel and exotic locales.

Similarly, his painting titled Monaco indicates his presence in that glamorous principality. A work depicting Monaco, sold at Sotheby's in 1978 for a significant sum of £6,400, underscores the appeal of these continental subjects. These paintings would have been executed with the same meticulous attention to detail that characterized his British landscapes, but applied to different architectural styles, vegetation, and qualities of light. Artists like Richard Parkes Bonington had earlier popularized continental scenes, and Carrick was part of a continuing tradition of British artists finding inspiration abroad.

Historical and Literary Themes: The Death of Arthur

Beyond landscape, John Mulcaster Carrick also engaged with historical and literary subjects, another key interest of the Pre-Raphaelites and Victorian artists in general. His most frequently cited work in this vein is The Death of Arthur, painted in 1862. This subject, drawn from Arthurian legend, was immensely popular in the Victorian era, fueled by Alfred, Lord Tennyson's Idylls of the King (the first set published in 1859).

Carrick’s depiction would have likely focused on the poignant final moments of King Arthur, possibly as he is taken away to Avalon. Such a scene offered scope for dramatic composition, emotional intensity, and the detailed rendering of armour, costume, and landscape, all appealing to Pre-Raphaelite sensibilities. Artists like William Dyce, Daniel Maclise, and later, Burne-Jones, also famously tackled Arthurian themes. Carrick's version, Bedivere and Arthur awaiting the barge - "The Death of King Arthur", as it is sometimes more fully titled, would have aimed for historical accuracy in its details, combined with a romantic and melancholic atmosphere. The painting’s influence has even extended into modern times, reportedly inspiring the cover art for a music album, demonstrating the enduring resonance of such imagery.

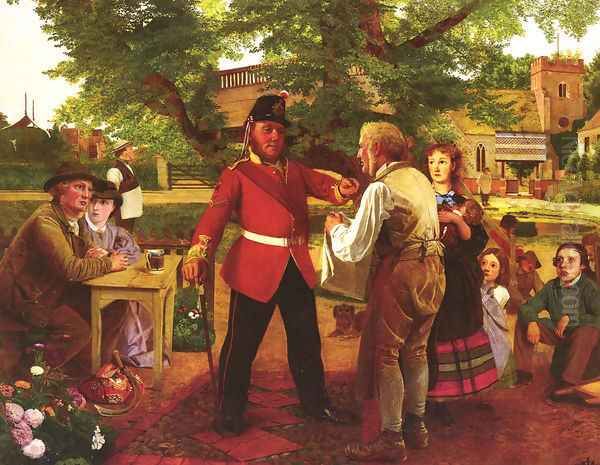

Another work mentioned in the context of historical painting is The Recruiting Sergeant. While less information is readily available about this specific piece, the title suggests a scene from military or social history, perhaps depicting the enlistment process, a theme explored by artists like John Frederick Herring Jr. with a focus on rural life, or with more dramatic overtones by others. Such genre scenes, if treated with Carrick's characteristic detail, would offer valuable insights into contemporary life or historical interpretation.

Artistic Associations: The Hogarth Club

An important aspect of an artist's career is their professional affiliations. John Mulcaster Carrick was recorded as an artist member of The Hogarth Club in 1859. The Hogarth Club (1858-1861) was a significant, albeit short-lived, exhibiting society founded by artists who felt constrained by the conservative attitudes of the Royal Academy. Its members included prominent figures associated with the Pre-Raphaelite movement, such as Ford Madox Brown, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Edward Burne-Jones, and William Morris, alongside other progressive artists like George Frederic Watts.

Carrick's membership in The Hogarth Club places him firmly within this avant-garde circle. The club provided an alternative venue for artists to showcase their work and fostered a sense of community among those pursuing new artistic directions. It was known for its exhibitions that often featured works considered too unconventional for the Royal Academy. Being part of this group indicates Carrick's alignment with the more progressive elements of the Victorian art world and his desire to associate with like-minded individuals who were pushing the boundaries of artistic convention.

Evolution of Style: A Shift Towards Naturalism?

The provided information suggests that, like some of his contemporaries, Carrick’s style may have evolved over time. While initially adhering closely to the meticulous detail of early Pre-Raphaelitism, it's noted that by the 1860s, as the initial fervor of the movement waned, some artists began to move towards a more naturalistic approach. This later naturalism, while still rooted in careful observation, might have involved a slightly broader handling of paint, a less intense focus on minute detail, and a greater emphasis on overall atmospheric effect, avoiding what some critics began to see as the excessive detail of earlier Pre-Raphaelite works.

Artists like Benjamin Williams Leader, who started with a highly detailed Pre-Raphaelite style, gradually adopted a more popular and somewhat looser landscape manner that brought him considerable success. John Brett, while maintaining incredible detail in works like The Val d'Aosta, also saw his style subtly shift over his long career. Sidney Richard Percy, part of the Williams family of painters, was known for his popular and often romanticized landscapes of Scotland and Wales, which, while detailed, aimed for a broader appeal. If Carrick followed a similar trajectory, his later works might exhibit a softening of the strict Pre-Raphaelite technique, perhaps incorporating a more unified tonality or a more painterly surface, while still retaining a fundamental commitment to the truth of the observed world. This was a common path for many Victorian landscape painters who sought to balance artistic integrity with public appeal and evolving aesthetic tastes.

Carrick in the Art Market: Exhibitions and Auction Records

The presence of John Mulcaster Carrick's works in auction records provides insight into his market standing, both during his lifetime and posthumously. He is known to have exhibited at major London venues, which would have included the Royal Academy, the British Institution, and the Society of British Artists at Suffolk Street. These exhibitions were crucial for an artist's reputation and sales.

His works have appeared at prominent auction houses such as Sotheby's, Lyons & Turnbull, and Roseberys, as well as regional ones like Parker's Fine Art Auctions. The sale of Monaco for £6,400 in 1978 is a notable price, indicating a strong collector interest at that time. Another coastal scene reportedly fetched £4,000. These figures, while subject to the fluctuations of the art market, demonstrate that Carrick's paintings have been, and continue to be, sought after by collectors of Victorian art. The inclusion of works like Enys Dodnam, Cornwall in auction catalogues further attests to their circulation and desirability.

The art market for Victorian painters, including those associated with Pre-Raphaelitism, has seen periods of intense interest and relative neglect. The detailed craftsmanship and narrative richness of these works often find renewed appreciation. Carrick's paintings, with their combination of skilled execution and appealing subject matter, fit well within this collecting category. Other landscape artists of the period, such as Atkinson Grimshaw with his moonlit urban scenes, or Myles Birket Foster with his charming rural idylls, also maintain a steady presence in the art market, each catering to specific tastes within the broader Victorian art landscape.

Legacy and Conclusion

John Mulcaster Carrick’s career spanned a significant period of British art history. He embraced the revolutionary ideals of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, applying its principles of "truth to nature" with particular success to landscape and coastal scenery. His meticulous attention to detail, his ability to capture the specific character of a place, whether the rugged shores of Cornwall or the sun-drenched vistas of the Mediterranean, mark him as a skilled and sensitive observer of the natural world.

His engagement with literary themes, notably Arthurian legend, connects him to a powerful current of Victorian romanticism and storytelling. Membership in The Hogarth Club aligns him with the progressive artists of his day. While perhaps not as widely known today as the leading figures of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood like Millais, Rossetti, or Hunt, or later masters like Burne-Jones, Carrick made a distinctive contribution. His works offer a window into the Victorian appreciation for nature, detail, and narrative.

The continued appearance of his paintings in the art market and their inclusion in discussions of Pre-Raphaelite landscape painting affirm his enduring, if modest, place in the annals of British art. John Mulcaster Carrick remains a compelling example of a Victorian artist who dedicated his considerable talents to rendering the beauty he found in the world around him, leaving behind a body of work that speaks of a deep connection to both the tangible reality of nature and the imaginative realm of legend. His paintings serve as a quiet reminder of the depth and diversity within the Victorian art scene, rewarding those who seek out the nuanced contributions of its many talented practitioners.