John Englehart (1867-1915) stands as a noteworthy, if somewhat overlooked, figure in the annals of American landscape painting. Active during a period of significant transition in American art, Englehart carved out a niche for himself with his commitment to a realistic depiction of the majestic scenery of the American West. Born in Chicago, Illinois, in 1867, he developed an early and profound fascination with the expansive territories west of the Mississippi, a region that was, for many Americans of his era, a potent symbol of untamed nature, opportunity, and a uniquely American identity. This romanticized yet deeply felt connection to the West would become the defining wellspring of his artistic endeavors.

Early Life and Westward Migration

The late 19th century was a dynamic period in American history, marked by industrial expansion, westward settlement, and a burgeoning national consciousness. For an aspiring artist like Englehart, growing up in a rapidly urbanizing center like Chicago, the call of the West, with its promise of raw beauty and grandeur, must have been particularly strong. It was this allure that prompted him to relocate to Northern California in the 1880s. This move was pivotal, placing him directly in the heart of the landscapes that would dominate his oeuvre. California, and the broader Pacific Northwest, offered a dramatic and diverse topography, from towering mountains and dense forests to rugged coastlines, providing inexhaustible inspiration.

At this time, American landscape painting was still heavily influenced by the legacy of the Hudson River School, whose artists, such as Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand, had established a tradition of depicting the American wilderness with a blend of detailed observation and romantic, often spiritual, sentiment. Later figures like Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Moran had brought this grand vision to the even more spectacular landscapes of the West, creating epic canvases that captivated the public imagination. However, by the time Englehart was establishing his career, new artistic currents, including Tonalism and American Impressionism, were gaining traction, challenging the dominance of the older schools.

A Commitment to Realism

John Englehart’s artistic path diverged from many of his contemporaries who were either embracing the atmospheric subtleties of Tonalism, championed by artists like George Inness and Dwight William Tryon, or the broken brushwork and light-filled palettes of Impressionism, as seen in the works of Childe Hassam or Theodore Robinson. Instead, Englehart remained steadfastly committed to a form of realism. His aim was not merely to represent the landscape but to convey its tangible presence, to make the viewer feel "as if they were there." This pursuit of verisimilitude set him apart.

His realism was characterized by a careful attention to detail, accurate rendering of geological formations, and a faithful depiction of light and atmosphere, without the overt romanticization or idealization that often marked the work of earlier Western painters. While Bierstadt, for instance, might amplify the drama of a scene for sublime effect, Englehart's approach appears to have been more direct and unembellished. This is not to say his work lacked feeling; rather, the emotional impact was intended to arise from the viewer's direct encounter with a convincingly rendered reality, rather than through overt artistic manipulation.

This dedication to a more straightforward realism, however, meant that Englehart was not always in step with the prevailing tastes of the art establishment or the broader public during his lifetime. The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw a growing appreciation for more subjective and stylistically innovative approaches to art. Consequently, Englehart was sometimes perceived as an "outsider" by those within the mainstream art circles, who perhaps found his style less "artistic" or modern than the emerging trends.

Depicting the Grandeur of the West

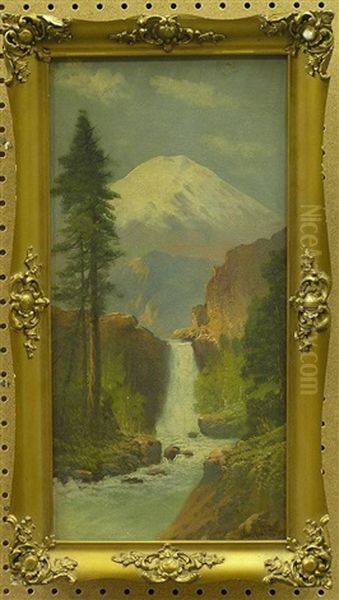

Englehart established a studio in San Francisco, a vibrant cultural hub on the West Coast, and from this base, he continued to explore and paint the region's magnificent scenery. His subjects often included the iconic mountains, forests, and waterways that defined the Western landscape. He sought to capture the scale and power of these natural wonders, translating their inherent majesty onto canvas. His works likely conveyed a sense of awe, but one rooted in the observable world rather than a transcendental or overtly spiritual interpretation.

The specific locales he painted would have included the Sierra Nevada mountains, the coastal ranges of California, and potentially scenes from Oregon and Washington, given his interest in subjects like Mount Rainier. His palette would have been attuned to the natural colors of these environments, capturing the deep greens of the forests, the varied hues of rock and earth, and the clear, often intense light of the West. His compositions would have been carefully structured to lead the viewer's eye into the scene, emphasizing depth and spatial relationships to enhance the feeling of immersion.

Representative Works and Their Significance

Among his known works, Indian on Horseback, dated 1903, offers a glimpse into another facet of his Western subjects. The portrayal of Native American figures was a common theme in Western art, often treated with varying degrees of romanticism, ethnographic interest, or as picturesque elements within the landscape. Without viewing the specific painting, one can surmise that Englehart, consistent with his realist approach, would have aimed for a depiction that was accurate in terms of attire and setting, perhaps less overtly heroic or sentimentalized than works by artists like Frederic Remington or Charles Marion Russell, who often focused on narrative and the "myth" of the West. Englehart's figure might have been presented more as an integral part of the landscape, observed with the same fidelity he applied to mountains and trees.

Another significant piece is the Mount Rainier Landscape. This work has a particularly interesting history, as it was reportedly begun by Englehart before his death in 1915 and later completed by another artist, Frederick W. Southworth, around 1930. Mount Rainier, a colossal volcanic peak in Washington state, is a subject that has challenged and inspired artists for generations. Englehart's initial vision for this painting would undoubtedly have aimed to capture its imposing scale and the unique atmospheric conditions surrounding it. The posthumous completion by Southworth highlights the esteem in which Englehart's work was held, at least by some, and ensures the preservation of what was likely a major undertaking. The collaborative nature of this piece, though necessitated by tragedy, adds a unique layer to its story.

While detailed information on a large corpus of his work is not widely available in mainstream art historical surveys, his paintings, when they appear, often showcase a meticulous hand and a profound respect for the natural world. Other works, sometimes titled generically as "Forest Scene" or similar descriptive names, would have further explored the diverse ecosystems of the West, from sun-dappled glades to the shadowy interiors of old-growth forests.

Exhibitions and Contemporary Reception

Englehart did achieve some measure of public recognition during his career. A notable instance was his participation in the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition held in Portland, Oregon, in 1905. This major event celebrated the centenary of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and showcased the progress and resources of the Pacific Northwest. For an artist specializing in Western landscapes, exhibiting here would have been a significant opportunity to present his work to a large and relevant audience. His inclusion suggests that his depictions of the region were considered of sufficient quality and interest for such a prestigious event.

Despite such participations, his steadfast realism, as mentioned, placed him somewhat at odds with the increasingly popular Impressionist and Tonalist movements. The art world was evolving, and the criteria for "important" art were shifting. Artists like John Singer Sargent, while a master realist in portraiture, also experimented with Impressionistic plein-air studies. The more avant-garde movements emerging in Europe, such as Fauvism and Cubism, were beginning to send ripples across the Atlantic, further pushing the boundaries of artistic expression in directions far removed from Englehart's dedicated naturalism.

Therefore, while respected for his skill, Englehart may not have enjoyed the widespread acclaim or financial success of some of his more stylistically "modern" contemporaries or those who, like Bierstadt or Moran, had capitalized on the earlier national fervor for grand, romantic Western epics. His position as an "outsider" was likely a reflection of his adherence to a style that, while possessing its own integrity, was not at the cutting edge of artistic fashion.

The Artistic Milieu: Realism in a Changing World

To fully appreciate Englehart's position, it's useful to consider the broader context of realism in American art at the turn of the 20th century. While the Hudson River School's detailed naturalism had elements of realism, it was often imbued with romantic or transcendental ideals. A more unvarnished realism had emerged with artists like Thomas Eakins and Winslow Homer, who depicted contemporary American life and nature with a searching honesty. Eakins, in particular, faced resistance for his unflinching portrayals.

In landscape painting, the influence of the French Barbizon School, with painters like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Théodore Rousseau, had encouraged a more direct and less idealized approach to nature in the mid-19th century, influencing American artists like William Morris Hunt and George Inness (in his earlier phase). Englehart's realism, though focused on the grander scale of the American West, shared this commitment to empirical observation.

However, by the late 19th century, "realism" itself was a complex term. The detailed, almost photographic, realism of some academic painters was being challenged by the "realism of light and color" explored by the Impressionists. Englehart's work seems to have aligned more with the former tradition of careful delineation and local color, perhaps finding kinship with the meticulous landscapes of artists associated with the Pre-Raphaelite influence in America, or the detailed geological studies seen in the survey art of figures like William Henry Holmes, though Englehart's primary aim was fine art rather than scientific illustration.

Collections and Legacy

John Englehart continued to paint and maintain his studio in San Francisco until his death in 1915. Today, much of his work is held in private collections, surfacing periodically at auctions. Institutions like MROCZKOWSKI SEARS AUCTION and MBA Seattle Auction have handled his paintings, indicating a continued, if specialized, market interest. The fact that his works are not widely represented in major public museum collections contributes to his relatively lower profile in comprehensive art historical narratives.

However, the assessment of an artist's significance can evolve. Englehart's commitment to realism, once perhaps seen as conservative, can now be appreciated for its own merits. His desire to provide an unmediated, immersive experience of the Western landscape offers a valuable counterpoint to the more romanticized or stylized interpretations of his contemporaries. His paintings serve as important visual documents of the American West as it appeared in his time, rendered with a sincerity and dedication to truth that is palpable.

Furthermore, his work has been recognized as an "important artistic inspiration for later landscape movements." This suggests that subsequent generations of artists, perhaps those reacting against abstraction or seeking a renewed connection with representational art, found value in Englehart's direct and honest approach to the natural world. His legacy, therefore, may lie not only in the intrinsic quality of his paintings but also in his role as a quiet torchbearer for a particular kind of artistic vision.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision of the West

John Englehart was an artist who remained true to his personal vision in an era of artistic flux. His deep love for the American West, born in Chicago and nurtured by his life in California, fueled a career dedicated to capturing its grandeur through a lens of steadfast realism. While his style may have set him apart from the dominant artistic trends of his time, leading to a somewhat "outsider" status, the integrity of his work endures.

His paintings, such as Indian on Horseback and the Mount Rainier Landscape, offer viewers a direct, immersive experience of the Western wilderness, emphasizing its tangible reality over romantic embellishment. He contributed to the rich tradition of American landscape painting by offering a distinct and honest perspective. Though perhaps not as widely celebrated as some of his contemporaries, John Englehart's dedication to his craft and his sincere depictions of the American West secure his place as a significant painter whose work continues to resonate with those who appreciate the enduring power of realistic representation and the timeless majesty of the natural world. His influence, though perhaps subtle, reminds us of the diverse currents that have always enriched the landscape of American art.