George Elbert Burr stands as a significant, if sometimes underappreciated, figure in American art, particularly renowned for his evocative etchings and drypoints that captured the sublime beauty and rugged wilderness of the American West, as well as picturesque scenes from his European travels. A prolific artist with a keen eye for detail and a profound sensitivity to atmosphere, Burr dedicated his life to the demanding craft of printmaking, leaving behind a vast legacy of works that continue to enchant viewers with their delicate precision and poetic sensibility. His journey from a young boy fascinated by art in the American Midwest to an internationally recognized etcher is a testament to his innate talent, unwavering dedication, and deep connection to the natural world.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born on April 14, 1859, in Monroe Falls, Ohio, George Elbert Burr's artistic inclinations emerged early. His formative years were spent in Cameron, Missouri, where his family relocated when he was ten. His father, a hardware store owner, perhaps inadvertently fostered his son's artistic pursuits, as the young Burr reportedly began experimenting with etching using zinc scraps and discarded metal found around his father's business. This early, self-directed exploration laid the groundwork for his future mastery of the medium.

His mother provided his initial art instruction, nurturing his burgeoning talent. While largely self-taught, Burr did seek formal training, however brief. He attended the Chicago Academy of Design (which would later become the Art Institute of Chicago) for a short period, from December 1878 to April 1879. This limited exposure to academic art education seems to have been his only formal instruction. Despite not completing an extensive academic program, the experience likely provided him with foundational skills and perhaps a glimpse into the broader art world. He soon returned to his family home, continuing to paint and even teach art, indicating a persistent drive to pursue his passion.

The Illustrator and the Path to Europe

Burr's professional career began to take shape as an illustrator. His meticulous drawing skills found an outlet in prominent publications of the era, including Harper's Magazine, Scribner's Magazine, Frank Leslie's Weekly, and The Cosmopolitan. This work provided him with a livelihood and honed his ability to translate scenes and ideas into compelling visual narratives, a skill that would serve him well in his printmaking.

A pivotal moment in Burr's career arrived in 1892. He received a monumental commission from the wealthy New York businessman and jade collector, Heber R. Bishop. Burr was tasked with creating one thousand etchings to illustrate the catalogue of Bishop's extensive jade collection, which was destined for the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This demanding project, which took several years to complete, was not only a significant artistic undertaking but also provided Burr with the financial means to embark on an extensive tour of Europe.

This European sojourn, lasting approximately five years, was profoundly influential. Traveling through Italy, Germany, Wales, and Sicily, among other regions, Burr immersed himself in the landscapes and historic architecture of the Old World. He diligently filled sketchbooks with drawings and created numerous watercolors, capturing the atmospheric effects of light and weather on ancient castles, rustic cottages, and scenic vistas. These visual notes would become an invaluable resource, providing the source material for a significant body of European-themed etchings he would produce in the years to come. Artists like John Ruskin, with his emphasis on detailed observation of nature and architecture, had already popularized such artistic pilgrimages, and Burr was following a well-trodden path, yet bringing his unique sensibility to it.

The Etcher's Craft: Precision and Poetry

Upon his return to the United States, Burr increasingly focused on original printmaking, particularly etching and drypoint. These intaglio techniques, which involve incising a design into a metal plate (usually copper), inking the plate, and then printing it under pressure, suited his meticulous nature and his desire to capture fine detail and subtle tonal gradations.

Etching involves coating the plate with an acid-resistant ground, through which the artist draws with a needle, exposing the metal. The plate is then immersed in acid, which bites into the exposed lines. Drypoint, by contrast, involves scratching directly into the plate with a sharp needle, raising a burr of metal alongside the incised line. When inked, this burr holds extra ink, producing a rich, velvety line distinct from the clean line of etching. Burr became a master of both, often combining them and employing various wiping techniques to achieve a wide range of atmospheric effects.

His prints are often characterized by what has been described as "the precision of a miniaturist." Despite their often small scale, they convey a remarkable sense of space, light, and texture. He was known for his ability to render the delicate tracery of winter branches, the soft haze of moonlight, the shimmering heat of the desert, and the dramatic cloud formations over mountain peaks. Unlike some of his contemporaries who sent their plates to professional printers, Burr took immense pride in printing his own editions, allowing him to control every aspect of the final image, from the richness of the ink to the tone of the paper. This hands-on approach was characteristic of the Etching Revival, a movement that emphasized the artist's direct involvement in the entire printmaking process, championed by artists like James McNeill Whistler and Sir Francis Seymour Haden.

The American West: A New Muse

Around 1906, due to health concerns, Burr sought a drier climate and moved to Denver, Colorado. This move marked a significant shift in his subject matter. While he continued to produce European scenes from his earlier sketches, the majestic landscapes of the American West became his primary inspiration. He built a brick house with a dedicated studio at 1325 Logan Street in Denver, equipped with his own printing press.

The Rocky Mountains, with their rugged peaks, deep canyons, and ever-changing atmospheric conditions, provided endless subject matter. He explored the Estes Park region, the Garden of the Gods, and the many creeks and forests near Denver. His works from this period capture the grandeur and sometimes the starkness of these high-altitude environments. He was not alone in his fascination; artists like Thomas Moran and Albert Bierstadt had earlier established the West as a powerful subject in American art, though Burr's approach was often more intimate and focused on the subtle moods of nature rather than purely epic vistas.

In 1924, Burr moved further south to Phoenix, Arizona, where he would spend the remainder of his life. The desert landscapes of Arizona and neighboring regions like California and New Mexico opened up a new visual vocabulary for him. The unique flora, such as saguaro cacti and palo verde trees, the dramatic rock formations, the vast expanses of sand, and the intense quality of light in the desert all found their way into his etchings and drypoints. He became a keen observer of the desert's subtle beauty, its resilience, and its unique atmospheric phenomena, from dust storms to brilliant sunsets.

Iconic Series: "Desert Set" and "Mountain Moods"

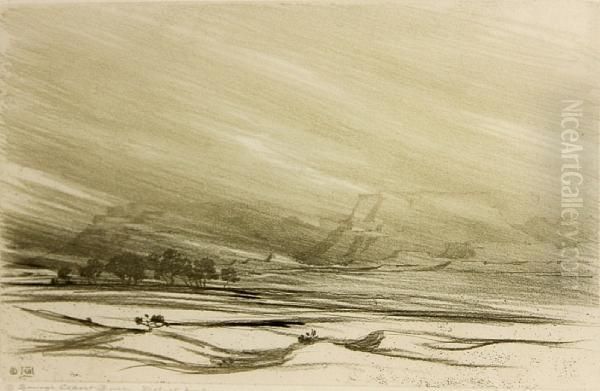

Among Burr's most celebrated works are his thematic series, notably the "Desert Set" (also referred to as the "Desert Mountain Series") and "Mountain Moods." These collections showcase his deep engagement with specific environments and his ability to convey a range of emotional and atmospheric responses to them.

The "Desert Set" comprises numerous etchings and drypoints depicting scenes from Arizona, New Mexico, and California. Works like Evening in Paradise Valley, Arizona, Giant Cacti, Arizona, and Old Cedar and Rocks reveal his fascination with the sculptural forms of desert plants, the texture of arid soil, and the dramatic interplay of light and shadow across the landscape. He captured the intense heat of midday, the cool clarity of twilight, and the ethereal glow of moonlight on the desert floor. These prints are not mere topographical records; they are poetic interpretations that evoke the unique spirit and atmosphere of the American Southwest.

"Mountain Moods," largely inspired by his time in Colorado, explores the varied character of the Rocky Mountains. Titles like Misty Moonlight, Estes Park, Colorado, The Sentinel Pine, and Bear Creek Canyon, Denver suggest the range of subjects and emotional tones. He depicted towering peaks shrouded in mist, tranquil forest interiors, and the dynamic energy of mountain streams. These works often emphasize the verticality and grandeur of the mountains, while also capturing more intimate moments of natural beauty. His ability to render the textures of rock, bark, and foliage with such precision, combined with his masterful handling of light, gives these prints a powerful presence.

Representative Masterpieces: A Closer Look

While Burr produced thousands of prints, certain works stand out as particularly representative of his skill and vision.

Canyon Rim, Arizona: This etching likely depicts a scene from the Grand Canyon or a similar dramatic gorge. Burr would have focused on the immense scale, the layered rock formations, and the play of light and shadow creating depth and volume. His meticulous line work would define the geological strata, while atmospheric perspective would convey the vast distances.

Misty Moonlight, Estes Park, Colorado: This work exemplifies Burr's ability to capture nocturnal scenes and subtle atmospheric effects. One can imagine soft, diffused moonlight filtering through trees or illuminating a mountain landscape, with delicate tonal gradations creating a sense of mystery and tranquility. The "misty" quality would be achieved through careful wiping of the plate or fine drypoint work.

Bear Creek Canyon, Denver: A subject close to his Denver home, this print would likely showcase the rugged beauty of a mountain canyon. Burr might have focused on the rushing water of the creek, the textures of the rocky canyon walls, and the surrounding pine trees. His skill in rendering moving water and the solidity of rock would be evident.

Oaks in Winter (exhibited 1914): This subject allowed Burr to display his mastery of depicting the intricate, bare branches of deciduous trees. Winter scenes were a favorite for etchers, as the stark forms and subtle light provided excellent opportunities for linear expression and tonal play. One can envision delicate, web-like branches against a soft, winter sky.

The Broken Bridge (exhibited 1925): Often, picturesque ruins or elements of human presence within a landscape attracted etchers. A broken bridge could symbolize the passage of time or the relationship between human endeavor and the forces of nature. Burr would have rendered the textures of stone or wood with his characteristic detail.

These and many other works demonstrate his consistent ability to translate his observations of nature into compelling and technically accomplished prints.

Artistic Style and Influences

Burr's style is characterized by its meticulous detail, delicate linework, and profound understanding of light and atmosphere. He was a master of creating rich, velvety blacks in his drypoints and subtle, nuanced grays in his etchings. His compositions are generally well-balanced, drawing the viewer into the scene without being overly dramatic. There is a quiet, contemplative quality to much of his work.

While largely self-taught in printmaking, Burr was undoubtedly aware of the broader trends in the medium. The Etching Revival, which began in France with artists like Charles Meryon and Félix Bracquemond and gained immense popularity in Britain and America through figures like Whistler and Haden, had created a fertile environment for printmakers. These artists championed the idea of the "painter-etcher," an artist who used etching as a primary means of original artistic expression, rather than merely for reproduction.

Burr's work shares affinities with other American etchers of his time, such as Joseph Pennell, known for his cityscapes and industrial scenes as well as landscapes, and Frank Weston Benson, celebrated for his etchings of waterfowl. While their subject matter often differed, they shared a commitment to technical excellence and expressive use of the etched line. One might also see a connection to the landscape sensibilities of the Hudson River School painters, like Asher B. Durand, in their detailed and reverent approach to nature, translated by Burr into the more intimate medium of printmaking. The atmospheric qualities in some of Burr's work could also be loosely linked to the Tonalist painters active in America at the turn of the century, such as George Inness or Dwight Tryon, who emphasized mood and soft light.

Burr and His Contemporaries

George Elbert Burr was an active participant in the art world, particularly within printmaking circles. He was a member of several prestigious organizations, including the New York Society of Etchers (later the Society of American Etchers), the Brooklyn Society of Etchers (which also evolved into the Society of American Etchers), the Chicago Society of Etchers, and even the Salmagundi Club in New York, a notable arts organization. His involvement in these societies provided him with exhibition opportunities and connections with fellow artists.

He exhibited alongside other artists who specialized in Western themes and printmaking. For instance, his work was sometimes grouped with that of Edwin Borein, known for his etchings and watercolors of cowboys and Western life, and Walter E. Bohl, another artist who depicted Southwestern landscapes. While their styles might have differed, their shared focus on the American West placed them in a similar artistic sphere.

The early 20th century saw a flourishing of American printmaking. Artists like Childe Hassam, primarily known as an Impressionist painter, also produced a significant body of etchings. John Taylor Arms became renowned for his incredibly detailed architectural etchings, showcasing a different kind of precision. Frank Duveneck, an influential painter and teacher, was also an early proponent of etching in America. Burr's dedication to landscape etching, particularly of the West, carved out a distinct niche for him among these talented contemporaries. His work offered a counterpoint to the urban scenes of Pennell or the society portraits that other artists might produce, focusing instead on the enduring power of the natural world.

Exhibitions and Recognition

Burr's work was widely exhibited during his lifetime and received considerable acclaim. His participation in the annual exhibitions of the Chicago Society of Etchers, such as the 1914 show at the Art Institute of Chicago where he exhibited Oaks in winter and The fairy glen, was typical of his engagement with the printmaking community. He also exhibited at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. (e.g., in 1921) and participated in international print exhibitions, such as the Sixth International Print Makers Exhibition in Los Angeles in 1925, where his print The Broken Bridge was shown.

His "Desert Series" was notably exhibited by the Detroit Institute of Arts Founders Society, indicating the institutional recognition his work received. Today, Burr's prints are held in the permanent collections of numerous major museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Art Institute of Chicago, the British Museum in London, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (French National Print Collection) in Paris, and the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. This widespread institutional acquisition underscores the lasting artistic merit and historical importance of his work.

The Prolific Printmaker: A Life's Dedication

One of the most remarkable aspects of George Elbert Burr's career is his sheer productivity. He is credited with creating over 1,000 watercolors and an astonishing number of prints, with estimates for his etchings and drypoints exceeding 25,000 impressions. This immense output is even more impressive considering that he printed most of his plates himself. This dedication to the entire process, from initial sketch to final print, speaks to his deep love for the craft.

He reportedly kept meticulous records of his prints. His commitment to quality and his personal involvement in the printing process ensured a high standard across his editions. Unlike some artists who might limit editions to create artificial scarcity, Burr seemed more interested in sharing his vision. There's an anecdote that he refused exclusive sales of his work, expressing a desire for his art to bring joy to many rather than being confined to a few. This democratic impulse, coupled with his prolific nature, helped to disseminate his work widely.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

After settling in Phoenix, Arizona, in 1924, Burr continued to be an active artist and a respected member of the local arts community. He served as the president of the Phoenix Fine Arts Association, contributing to the cultural development of his adopted city. He continued to explore and sketch the surrounding desert landscapes, translating his observations into new etchings and drypoints until his death on November 17, 1939, in Phoenix.

George Elbert Burr's legacy is that of a master printmaker who captured the diverse beauty of both European and American landscapes with exceptional skill and sensitivity. He was a key figure in the American Etching Revival, particularly distinguished by his focus on the American West. His work provides a valuable historical record of landscapes that have since changed, but more importantly, it conveys a timeless appreciation for the moods and majesty of nature.

His prints continue to be sought after by collectors and admired by art lovers for their technical brilliance, their atmospheric depth, and their quiet, poetic beauty. He demonstrated that the intimate medium of etching could convey the grandeur of vast deserts and towering mountains as effectively as any large-scale painting. Through his thousands of meticulously crafted prints, George Elbert Burr left an indelible mark on the history of American art, securing his place as one of the nation's most accomplished and dedicated etchers. His ability to evoke the spirit of place, whether a sun-drenched Arizona canyon or a misty Welsh valley, remains his most enduring achievement.