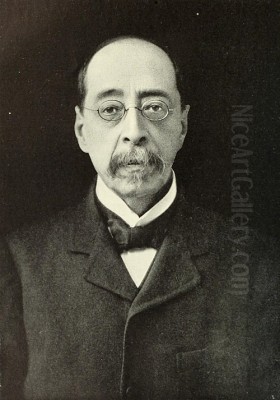

John La Farge stands as a towering figure in American art history, a multifaceted artist whose career spanned painting, stained glass, mural decoration, and writing. Active during the latter half of the 19th and early 20th centuries, La Farge was a central personality in the American Renaissance, a period characterized by a renewed interest in classical ideals, mural painting, and the integration of arts with architecture. His relentless experimentation, intellectual depth, and unique synthesis of diverse influences set him apart, leaving an indelible mark on the nation's cultural landscape.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in New York City on March 31, 1835, John La Farge entered a world of privilege and culture. His parents were wealthy French émigrés, Jean Frédéric de la Farge and Louise Joséphine Binsse de Saint-Victor. Growing up in a cosmopolitan household, he was bilingual in French and English from an early age, immersed in literature and the arts. This cultured upbringing provided a foundation for his later intellectual and aesthetic pursuits. His family's Catholic faith also subtly informed his later engagement with religious subject matter.

La Farge received a broad education, attending St. John's College (now Fordham University) in the Bronx and later Mount St. Mary's College in Maryland. Initially, he pursued legal studies, following a more conventional path expected of someone of his social standing. However, his passion for art, nurtured since childhood through drawing lessons and visits to galleries, proved irresistible. A pivotal trip to Europe in 1856 solidified his commitment to becoming an artist.

During his European sojourn, La Farge immersed himself in the art capitals, particularly Paris. He briefly studied painting with the renowned academic painter Thomas Couture, whose other students included Édouard Manet. More significantly, he spent countless hours studying the Old Masters in the Louvre and other collections, absorbing lessons in composition, color, and technique. He also formed connections with prominent literary and artistic figures, expanding his intellectual horizons. This period was crucial for developing his discerning eye and eclectic taste.

Upon returning to the United States, La Farge sought further instruction. He moved to Newport, Rhode Island, in 1859, a fashionable resort town that was also becoming an artistic hub. There, he studied with William Morris Hunt, an American painter who had worked with Jean-François Millet and the Barbizon School painters in France. Hunt encouraged direct observation of nature and a looser, more expressive brushwork, which resonated with La Farge's evolving sensibilities. Newport provided a stimulating environment where he began to seriously develop his skills as a painter.

The Painter: Light, Color, and Nature

La Farge's early painting career focused primarily on landscapes and still lifes, often executed outdoors in the manner encouraged by Hunt and influenced by the Barbizon School's emphasis on naturalism. He developed a profound sensitivity to the effects of light and atmosphere, striving to capture the fleeting nuances of the natural world. His landscapes, often depicting the coastal scenery around Newport, possess a quiet intimacy and a subtle poetry.

His still life paintings from this period are particularly noteworthy for their innovative approach to color and composition. Works like Flowers on a Window Ledge (c. 1861) demonstrate his early mastery. Rather than merely replicating the appearance of objects, La Farge explored the interplay of light, color, and form with an almost scientific curiosity, yet imbued the results with deep feeling. He was influenced by contemporary color theories and the rich palettes of artists like Eugène Delacroix, whom he admired greatly.

La Farge's interest in Japanese art, which began in the early 1860s, also profoundly impacted his painting. He was among the first American artists, alongside contemporaries like James Abbott McNeill Whistler, to seriously study and collect Japanese prints (ukiyo-e). The asymmetrical compositions, flattened perspectives, bold outlines, and decorative patterns found in Japanese art offered a compelling alternative to Western conventions. These elements gradually permeated his work, visible in the arrangement of forms and the use of empty space.

Throughout the 1860s and 1870s, La Farge continued to refine his painting technique, experimenting with different media, including watercolor and oil. His watercolors, particularly those produced during later travels, are celebrated for their luminosity and fluidity. He often tackled complex subjects, including allegorical and religious themes, bringing a modern sensibility and psychological depth to traditional iconography. Works like The Last Valley—Paradise Rocks, Newport (1867-68) showcase his ability to blend realistic observation with a sense of mystery and philosophical contemplation.

Revolutionizing Stained Glass

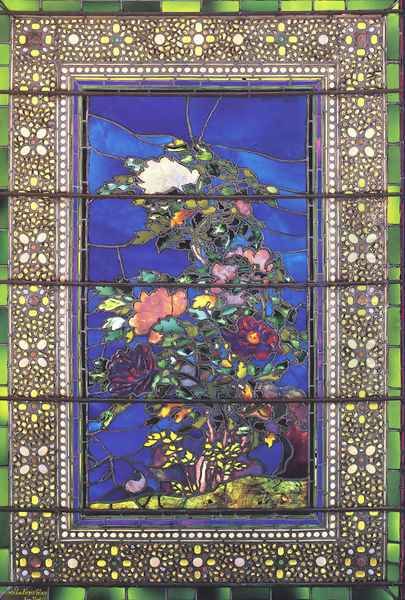

While accomplished as a painter, John La Farge's most revolutionary contributions arguably lie in the field of stained glass. Dissatisfied with the quality and limitations of commercially available glass in the mid-19th century, which largely relied on painting onto clear glass, La Farge embarked on a period of intense experimentation in the 1870s. He sought to achieve color and visual effects through the inherent properties of the glass itself, rather than surface application.

His breakthrough came with the development and patenting of opalescent glass – a milky, opaque, or semi-opaque glass with internal variations in color and texture. This type of glass could diffuse light beautifully and allowed for subtle gradations of tone and hue within a single piece. La Farge combined this with innovative techniques such as layering multiple pieces of glass to achieve greater depth and richness, using molded or "jeweled" glass for textural effects, and varying the thickness and placement of lead lines (came) for expressive purposes.

This new approach fundamentally transformed stained glass from a primarily illustrative medium into one capable of painterly effects, rivaling the expressive potential of oil painting. La Farge essentially treated glass as a palette, composing with light and color in a way that had not been done before in America. His methods allowed for unprecedented subtlety in depicting drapery, landscapes, and atmospheric effects.

The commission for the interior decoration of Trinity Church in Boston, designed by architect Henry Hobson Richardson and completed in 1876, provided La Farge with a major opportunity to showcase his innovations in both mural painting and stained glass. His windows for Trinity Church marked a turning point in American ecclesiastical art, demonstrating the power and beauty of his new techniques. They moved away from the thin, graphic style of European Gothic Revival glass towards a richer, more pictorial aesthetic.

La Farge's pioneering work inevitably brought him into competition, and later conflict, with another major figure in American decorative arts: Louis Comfort Tiffany. Tiffany also began experimenting with opalescent glass around the same time, and while their initial relationship may have involved some sharing of ideas, it devolved into rivalry. La Farge patented certain techniques, including the layering of glass, in 1880. A subsequent, protracted legal battle ensued over the invention of opalescent glass, which ultimately contributed to the financial difficulties that plagued La Farge throughout his career, even leading to the bankruptcy of his glass company. Despite these struggles, La Farge's primacy as the innovator of American opalescent stained glass is generally acknowledged by art historians.

Murals and the American Renaissance

John La Farge was a key proponent of the American Renaissance, a movement that sought to elevate American art and architecture through the integration of painting, sculpture, and decorative arts, often drawing inspiration from classical and Renaissance precedents. Mural painting was central to this ideal, and La Farge became one of its leading practitioners. His deep knowledge of art history, combined with his technical skill, made him ideally suited for large-scale decorative projects.

His work at Trinity Church, Boston, included not only stained glass but also extensive mural decorations covering the walls and ceilings of the massive central tower. Working under immense time pressure, La Farge directed a team of assistants to execute his designs, which blended Byzantine, Romanesque, and Renaissance influences into a cohesive and opulent scheme. This project established his reputation as a master decorator capable of handling complex architectural spaces.

Following the success of Trinity Church, La Farge received numerous commissions for murals and decorations in churches, public buildings, and private residences. Notable examples include his work for the Church of the Ascension (1886-88) and St. Paul the Apostle Church (1887-99), both in New York City. His mural The Ascension is considered one of the masterpieces of American mural painting, demonstrating his ability to handle complex figural compositions and create a sense of spiritual grandeur.

He also executed important secular murals, such as Athens (1898) for the Walker Art Building at Bowdoin College and four large lunettes representing aspects of law – Moses Receiving the Law on Mount Sinai, The Recording of Precedents, The Adjustment of Conflicting Interests, and Socrates and His Friends Discuss the Nature of Justice (finished 1903) – for the Minnesota State Capitol building in St. Paul. These works showcased his erudition and his skill in adapting historical styles to contemporary American contexts.

La Farge often collaborated with leading architects of the day, including H.H. Richardson and the firm of McKim, Mead & White, whose principal Stanford White was a close associate. These collaborations were central to the American Renaissance ideal of unifying art and architecture. His decorative work extended beyond murals and glass to include overall interior design schemes, demonstrating his versatility and holistic approach to creating beautiful environments.

Travels, Japonisme, and Global Perspectives

Travel was a vital source of inspiration and intellectual renewal for John La Farge throughout his life. His journeys provided him with fresh subject matter, exposed him to different cultures and artistic traditions, and deepened his understanding of light and color under varying conditions. His travels were not mere sightseeing trips but rather intensive periods of observation, sketching, and reflection.

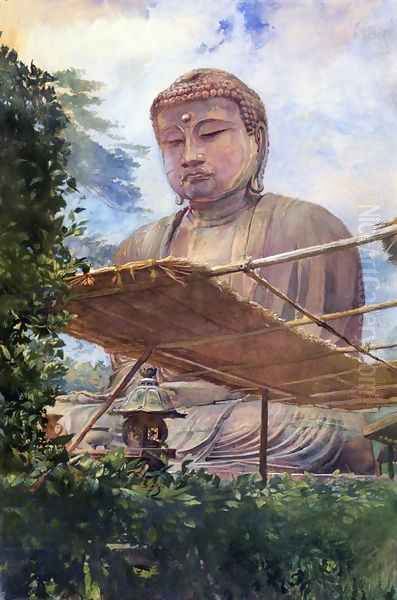

A particularly influential journey occurred in 1886 when La Farge traveled to Japan accompanied by his close friend, the historian and writer Henry Adams. This trip immersed him in the culture and aesthetics that had fascinated him for decades. He studied Japanese art and architecture firsthand, met with local artists, and observed traditional customs and landscapes. The experience profoundly affected his artistic vision, reinforcing his appreciation for asymmetry, suggestion, and the integration of art into daily life. His writings from this period, published as An Artist's Letters from Japan (1897), provide valuable insights into his observations and the impact of Japanese culture on a Western artist.

Following the Japan trip, La Farge and Adams continued their travels in 1890-91, venturing into the South Seas, visiting Hawaii, Samoa, Tahiti, and Fiji. This journey exposed La Farge to entirely different landscapes, cultures, and qualities of light. He was captivated by the vibrant colors, lush vegetation, and traditional ways of life of the Pacific Islanders. He produced numerous stunning watercolors during this trip, capturing the exotic beauty and tranquil atmosphere of the islands with remarkable sensitivity and luminosity. These works, such as Entrance to Tautira Valley, Tahiti, Waterfall (1891), are considered among the highlights of his oeuvre in watercolor.

These travels broadened La Farge's artistic vocabulary and reinforced his belief in the universality of aesthetic principles found across different cultures. His engagement with non-Western art, particularly Japanese art (Japonisme), was not superficial imitation but a deep assimilation of principles that enriched his own unique style. He skillfully integrated elements of Japanese composition and perspective into his paintings, watercolors, and even stained glass designs, contributing significantly to the cross-cultural dialogues occurring in the art world at the time.

Intellectual Life, Writings, and Friendships

John La Farge was more than just a visual artist; he was a true intellectual, a man of wide-ranging interests and profound learning. His library was extensive, and he was well-versed in literature, history, theology, philosophy, and even contemporary scientific thought, including Darwin's theories. This intellectual depth informed his art, lending it a richness and complexity that transcended mere representation. He saw art as a form of inquiry, a way of exploring the fundamental questions of existence, beauty, and spirituality.

He was also a gifted writer and lecturer. His book Considerations on Painting (1895), based on lectures delivered at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, offers articulate insights into the principles of art, drawing upon his vast knowledge of art history and his own practical experience. As mentioned, An Artist's Letters from Japan (1897) provides a fascinating account of his travels and cross-cultural observations. His writings reveal a sophisticated mind capable of nuanced reflection on aesthetics, technique, and the role of the artist in society.

La Farge moved in prominent social and intellectual circles, maintaining close friendships with leading figures of his time. His friendship with Henry Adams was particularly significant, marked by shared intellectual curiosity and extensive travels. He was also acquainted with major literary figures like Henry James, whose early novels were reportedly influenced by his interactions with La Farge during their time in Newport. His studio in the Tenth Street Studio Building in New York City was a hub for artists and intellectuals.

He was actively involved in the art organizations of his day, helping to shape the institutional landscape of American art. He was a founder of the Society of American Artists, established in opposition to the more conservative National Academy of Design, and later served as President of the National Society of Mural Painters. Through these roles, he advocated for higher standards in American art and promoted the integration of the arts. His circle included prominent artists like the sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, and painters such as Winslow Homer, Elihu Vedder, Kenyon Cox, and Edwin Blashfield, all key figures in the American art scene.

Personal Complexities and Challenges

Despite his artistic achievements and intellectual brilliance, John La Farge's life was not without its difficulties and complexities. His marriage to Margaret Mason Perry, a descendant of Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry, which began in 1860, faced significant strains. Sources suggest periods of estrangement and near-dissolution, compounded by La Farge's intense dedication to his work and perhaps other personal failings, including reports of an affair with an assistant. The demands of his career often kept him away from his family, which included several children.

Furthermore, La Farge struggled with financial management throughout his life. Despite receiving major commissions and achieving critical acclaim, his business ventures, particularly his stained glass company, were often precarious. The costly experiments with glass, coupled with the lengthy and expensive lawsuit against Tiffany, led to repeated financial crises and bankruptcies. This tension between artistic ambition and commercial reality created significant stress. Some anecdotes, like the story of him being unaware of the birth of his youngest child due to preoccupation with legal matters, highlight the personal toll of these professional struggles.

There were also unusual incidents, such as the reported interruption of work on a large mural due to the excessive weight of the canvas, which some contemporaries interpreted through a lens of the supernatural or inexplicable. While likely having a practical explanation, such stories contribute to the complex and sometimes enigmatic image of the artist. These personal and financial challenges paint a picture of a man deeply committed to his artistic vision, sometimes at great personal cost, navigating the often-conflicting demands of art, business, and family life in the Gilded Age.

Later Years, Recognition, and Legacy

In his later years, John La Farge continued to work actively, undertaking major mural projects and producing exquisite stained glass windows and watercolors. He received numerous honors recognizing his contributions to American art. He was awarded the Legion of Honour by the French government and received honorary degrees from universities like Yale and Princeton. His reputation as a leading figure in American art was firmly established, even as new artistic movements began to emerge.

His influence extended through his students and assistants, and through the example set by his innovative techniques, particularly in stained glass. While Louis Comfort Tiffany achieved greater commercial success and name recognition, La Farge's pioneering role in developing opalescent glass and his more painterly, deeply considered approach remain highly significant. His work demonstrated that stained glass could be a major art form, capable of profound expression.

John La Farge died in Providence, Rhode Island, on November 14, 1910, at Butler Hospital, after a period of illness. He was buried in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York. At the time of his death, he was widely regarded as one of America's most distinguished artists, a "Renaissance man" whose talents spanned multiple disciplines.

His legacy lies in his technical innovations, particularly the invention and artistic application of opalescent glass, which revolutionized the medium in America. It also resides in his significant contributions to the American Renaissance through his masterful mural paintings and his advocacy for the integration of the arts. His paintings and watercolors are admired for their sensitivity to light and color, their intellectual depth, and their unique synthesis of Western and Eastern aesthetics. He demonstrated that an American artist could engage with global traditions while forging a distinctly personal and modern vision.

Enduring Significance

John La Farge remains a pivotal figure for understanding American art during a period of significant transformation and growing national confidence. His career embodies the aspirations and complexities of the Gilded Age and the American Renaissance. He was an artist of exceptional intelligence, sensitivity, and ambition, constantly pushing the boundaries of his chosen media.

His exploration of light and color, whether in oil, watercolor, or glass, reveals a profound connection to the visual world and a desire to capture its ephemeral beauty. His engagement with diverse artistic traditions, from the Old Masters to Japanese prints, showcases his cosmopolitan outlook and his ability to synthesize influences into a unique artistic language. His pioneering work in stained glass fundamentally changed the medium in the United States, paving the way for subsequent generations of artists.

While perhaps less famous today than some of his contemporaries like Tiffany or Winslow Homer or John Singer Sargent, La Farge's contributions were foundational. He elevated the status of decorative arts, championed the integration of art and architecture, and brought a deep intellectual and spiritual dimension to his work. As an innovator, a thinker, and a master craftsman across multiple fields, John La Farge secured his place as one of the most important and versatile American artists of the 19th century.