John Tenniel stands as a monumental figure in the history of British art, a master illustrator and political cartoonist whose work not only defined the visual landscape of the Victorian era but continues to resonate with audiences today. His meticulous craftsmanship, imaginative power, and incisive wit left an indelible mark on book illustration, particularly through his iconic imagery for Lewis Carroll's "Alice" books, and on political commentary through his decades of work for Punch magazine. His life and career offer a fascinating window into the artistic, social, and political currents of 19th-century Britain.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations

Born in Bayswater, London, on February 28, 1820, John Tenniel was the son of John Baptist Tenniel, a fencing and dancing master of Huguenot descent, and Eliza Maria Tenniel. From a young age, Tenniel displayed a prodigious talent for drawing, a passion that seemed to overshadow any formal academic pursuits. While he did briefly attend the Royal Academy Schools, he found the traditional methods of instruction stifling and largely became a self-taught artist, honing his skills through diligent practice and the close study of classical sculpture and the works of earlier masters.

A formative, albeit unfortunate, incident in his youth significantly impacted his life. Around the age of 20, while fencing with his father, Tenniel suffered a serious injury to his right eye from his father's foil, which had accidentally lost its protective tip. Over time, the sight in this eye deteriorated, eventually leading to near-complete blindness in it. Remarkably, Tenniel concealed the severity of the injury from his father for many years, a testament to his stoic and considerate nature. This physical challenge, however, did not impede his artistic output; indeed, some have speculated it may have contributed to his meticulous, almost photographic memory for detail, which served him well in his illustration work.

His formal artistic debut came in 1836 when he submitted an oil painting to the Society of British Artists exhibition. However, it was in the realm of illustration that he would find his true calling. An early significant commission was for Samuel Carter Hall's The Book of British Ballads in 1842, where his contributions began to showcase his distinctive style. This was followed by illustrations for an edition of Aesop's Fables in 1848, a project for which he reportedly made detailed studies of animals at the London Zoo, demonstrating his commitment to accuracy even within fantastical contexts.

The Westminster Fresco Competition and Early Recognition

A notable early opportunity for Tenniel arose from the competitions held to decorate the new Houses of Parliament at Westminster, rebuilt after the fire of 1834. In 1845, he submitted a 16-foot cartoon (a full-scale preparatory drawing) titled "An Allegory of Justice" for a fresco competition. While he did not win the main prize, his work was commended, and he received a £200 premium and a commission to paint a fresco of St. Cecilia, from Dryden's "Song for St. Cecilia's Day," in the Upper Waiting Hall (or "Poets' Hall") of the House of Lords.

This project, though prestigious, highlighted the challenges of fresco painting in the damp English climate and with the available materials. Tenniel, like many of his contemporaries involved in the Westminster decorations, such as William Dyce, Daniel Maclise, and Charles West Cope, found the medium difficult. Despite these challenges, the commission brought him public recognition and further established his reputation as a skilled draughtsman. His involvement with such a national project, alongside prominent artists of the day, was a significant step in his burgeoning career.

Joining Punch: A Half-Century of Political Satire

The most defining professional relationship of Tenniel's career began in December 1850 when he was invited by Mark Lemon, the editor of Punch, to join the magazine's staff as a joint chief cartoonist alongside the already established John Leech. Tenniel replaced Richard "Dicky" Doyle, a talented illustrator who had resigned due to Punch's increasingly critical stance towards the Papacy and Roman Catholicism, a position Doyle, a devout Catholic, could not reconcile with his conscience.

Punch, or The London Charivari, founded in 1841, had rapidly become Britain's leading satirical magazine, wielding considerable influence on public opinion. Its weekly political cartoon, often referred to as the "big cut," was a powerful tool for commentary on national and international affairs. Tenniel's arrival marked the beginning of an extraordinary fifty-year tenure, during which he would produce over 2,300 cartoons for the magazine, as well as numerous smaller drawings and designs for its almanacs and pocket-books.

Initially, Tenniel shared the responsibility for the main political cartoon with Leech. However, after Leech's untimely death in 1864, Tenniel became Punch's principal political cartoonist, a role he fulfilled with unparalleled consistency and impact until his retirement in January 1901. His cartoons covered the gamut of Victorian political life: the Crimean War, the Indian Mutiny, the American Civil War (where Punch often took a pro-Confederate stance, later regretted), Irish Home Rule, the rise of Gladstone and Disraeli, colonial expansion, and social reforms.

Tenniel's approach to political cartooning was characterized by a classical dignity and a powerful sense of symbolism. He often employed allegorical figures, national personifications (like Britannia, John Bull, or the American Brother Jonathan, later Uncle Sam), and animal symbolism to convey complex political messages. His drawing style was precise and strong, perfectly suited for the wood engraving process used to reproduce illustrations in print at the time. He worked closely with skilled engravers, most notably the Dalziel Brothers (Edward and George Dalziel) and later Joseph Swain, who expertly translated his pencil drawings onto the woodblock.

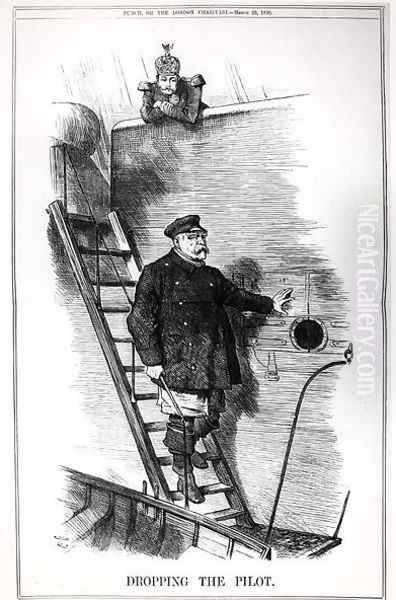

One of his most famous and enduring Punch cartoons is "Dropping the Pilot" (1890), depicting the German Kaiser Wilhelm II dismissing his veteran Chancellor, Otto von Bismarck. This image became an instant classic, its title entering the political lexicon. Other notable cartoons include "The Nemesis of Neglect" (1888), a haunting image commenting on the Jack the Ripper murders and social conditions in the East End, and his many depictions of the "Irish Question," which often reflected the prevalent anti-Irish sentiment of the time, though his portrayals evolved over the decades. His work, while sometimes reflecting the biases of his era, consistently demonstrated a masterful command of visual rhetoric. His contemporaries at Punch or in similar satirical veins included artists like George du Maurier, who later succeeded him in some capacities, and across the Channel, the French master of caricature, Honoré Daumier, whose style was more overtly dynamic and less classically restrained than Tenniel's.

The Alice Illustrations: A Timeless Collaboration

While his work for Punch secured his contemporary fame and influence, it is arguably his illustrations for Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There (1871) that have ensured his lasting international renown. This collaboration, though at times fraught with the creative tensions common between author and illustrator, produced a set of images that are inextricably linked with Carroll's text.

Lewis Carroll (the pen name of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, a mathematics lecturer at Christ Church, Oxford) initially illustrated Alice's Adventures Under Ground (the manuscript version of the story) himself. However, recognizing his limitations as an artist, he sought a professional illustrator for the published version. Encouraged by the author and artist John Ruskin and the painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti, a leading figure of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Carroll approached Tenniel, whose work in Punch and for books like Aesop's Fables he admired.

Tenniel was initially hesitant, already burdened with his Punch commitments. However, he was eventually persuaded. The collaboration was meticulous, with Carroll providing detailed instructions and often sketches for the illustrations. Tenniel, a consummate professional, translated these ideas into his own distinct visual language. He insisted on a high degree of artistic control, sometimes clashing with Carroll's precise vision. For instance, Carroll had a specific model in mind for Alice, Mary Hilton Badcock, but Tenniel preferred to draw from his own imagination, resulting in an Alice who, while perhaps influenced by photographs of Alice Liddell (Carroll's initial muse) and other contemporary children, became uniquely Tenniel's creation.

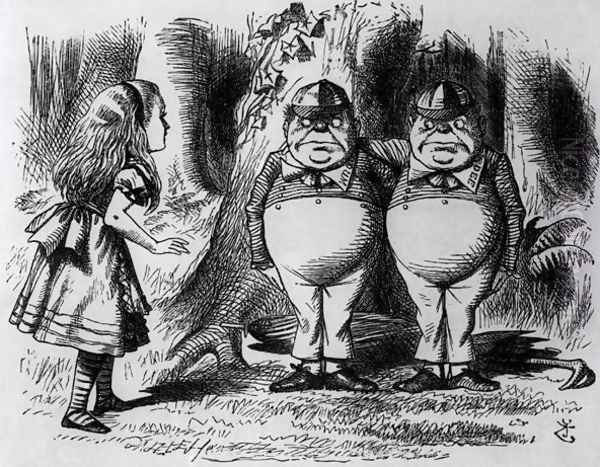

The 92 illustrations Tenniel created for the two Alice books are masterpieces of fantasy and characterization. His depictions of Alice herself, the White Rabbit, the Cheshire Cat, the Mad Hatter, the March Hare, the Queen of Hearts, Tweedledum and Tweedledee, and the Jabberwock are definitive. He imbued these fantastical creatures with a curious solidity and psychological depth, making Wonderland and the Looking-Glass world strangely believable. His style, characterized by clear outlines, precise detail, and a masterful use of cross-hatching to create tone and form, was perfectly suited to the wood engraving process.

A famous anecdote highlights Tenniel's exacting standards: he was so dissatisfied with the printing quality of the first edition of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865), particularly the way his illustrations appeared, that he urged Carroll to have it suppressed. Carroll complied, and a new edition was printed by Richard Clay, which met with Tenniel's approval and became the standard. This incident underscores Tenniel's commitment to the integrity of his artwork.

The success of the Alice books was phenomenal, and Tenniel's illustrations were a crucial component of their appeal. They have been endlessly reproduced, imitated, and parodied, becoming part of the global cultural consciousness. His work set a new standard for children's book illustration, influencing generations of artists, including later luminaries like Arthur Rackham and Edmund Dulac, who, while developing their own distinct styles, worked within the tradition of detailed, imaginative illustration that Tenniel had helped to popularize.

Artistic Style, Technique, and Working Methods

Tenniel's artistic style was characterized by its precision, clarity, and strong sense of composition. He possessed an exceptional memory for visual detail, which was particularly useful given his impaired eyesight. He rarely drew directly from life for his Punch cartoons, preferring to work from memory and imagination, meticulously planning his compositions. His figures, whether human or animal, often had a sculptural quality, reflecting his early study of classical art.

His line work was firm and incisive, ideal for the wood engravers who translated his drawings. He typically drew in pencil on paper, and these drawings were then transferred (often by tracing) onto the surface of a boxwood block. The engraver would then carve away the wood around the lines, leaving the image in relief to be inked and printed. Tenniel maintained a close working relationship with his engravers, particularly Joseph Swain, ensuring that the final printed image faithfully represented his intentions.

While his Alice illustrations are imbued with a sense of fantasy, his political cartoons often employed a more classical or allegorical mode. He was a master of physiognomy, able to capture a likeness or convey character with a few deft strokes. His compositions were carefully balanced, often with a theatrical sense of staging that made his political messages clear and impactful. Despite the often serious or critical nature of his subjects, there was usually an underlying dignity and restraint in his work, avoiding the grotesque or overly savage caricature that characterized some of his predecessors, like James Gillray or Thomas Rowlandson, or even some of his contemporaries.

Tenniel was not a prolific painter in oils, though he did exhibit occasionally. His primary medium was black and white illustration. He did, however, produce some watercolour versions of his Alice illustrations later in life, and some of his drawings were hand-coloured for special editions. His strength lay in his draughtsmanship and his ability to create memorable, iconic images that could be widely reproduced.

Other Notable Works and Contributions

Beyond Punch and the Alice books, Tenniel illustrated a number of other volumes, though none achieved the same level of fame. These included:

Thomas Moore's Lalla Rookh (1861), an oriental romance for which he provided 69 drawings.

The Ingoldsby Legends (1864) by Richard Harris Barham, contributing to an edition alongside other prominent illustrators like George Cruikshank and John Leech. Cruikshank, an earlier giant of British illustration and caricature, particularly known for his work with Charles Dickens, represented an older, more boisterous tradition.

Poe's "The Raven," illustrated for an 1858 gift book.

He also designed stained glass windows and mosaics, though these form a smaller part of his oeuvre. His versatility extended to creating humorous social vignettes and character studies, many of which appeared in Punch's Pocket Books. He was less associated with the sentimental or idyllic style of children's illustration that became popular with artists like Kate Greenaway or Randolph Caldecott later in the century, though his Alice certainly possessed a charm that appealed to children. His focus remained largely on narrative clarity and characterful, often satirical, depiction.

Personal Life, Character, and Later Years

Tenniel was known as a quiet, reserved, and gentlemanly figure. Despite his public prominence through Punch, he was not a seeker of the limelight and preferred a relatively private life. He married Julia Giani in 1854, but tragically, she died just two years later from tuberculosis. Tenniel never remarried and lived for many years with his sister, Victoria, and later with his brother-in-law.

He was described by contemporaries as amiable and modest, though firm in his artistic judgments. His long and consistent output for Punch, often working to tight weekly deadlines, attests to his professionalism and dedication. He was a member of the Garrick Club, a London gentlemen's club popular with men of arts and letters, where he would have socialized with other artists, writers, and actors of the day, including figures like William Makepeace Thackeray, who was also a contributor to Punch.

In 1893, in recognition of his artistic achievements and his significant contributions to public life through his work for Punch, John Tenniel was knighted by Queen Victoria upon the recommendation of Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone. This was a significant honor, making him one of the first illustrators or cartoonists to receive such a distinction, elevating the status of his profession. Other Victorian artists who received knighthoods included painters like Frederic Leighton, John Everett Millais (a founding member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood alongside William Holman Hunt and Rossetti), and Lawrence Alma-Tadema.

Tenniel retired from Punch in January 1901, shortly before the death of Queen Victoria. His final cartoon for the magazine was titled "Valete" (Farewell). His departure marked the end of an era for the publication. He continued to live in London, enjoying a relatively quiet retirement, though his eyesight, particularly in his good left eye, began to fail in his later years, making drawing difficult.

Death and Enduring Legacy

Sir John Tenniel died at his home in Maida Hill, London, on February 25, 1914, just three days short of his 94th birthday. He was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery. His death was widely mourned, and obituaries celebrated his immense contribution to British art and visual culture.

Tenniel's legacy is twofold. Firstly, his political cartoons for Punch provide an unparalleled visual record of Victorian Britain, capturing its triumphs, anxieties, and transformations. His work set a standard for political cartooning that emphasized strong draughtsmanship, clear messaging, and a certain gravitas, influencing subsequent generations of political artists.

Secondly, and perhaps more enduringly on a global scale, his illustrations for the Alice books have become definitive. It is almost impossible to imagine Alice, the Mad Hatter, or the Cheshire Cat without Tenniel's imagery springing to mind. These illustrations have transcended their original context, becoming iconic representations of Carroll's fantastical world, shaping the visual imagination of countless readers and inspiring numerous adaptations in film, theatre, and other media. His ability to give concrete, memorable form to the abstract and the absurd was unparalleled.

His influence extended to the "Golden Age of Illustration" that followed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with artists like Arthur Rackham, Edmund Dulac, Kay Nielsen, and W. Heath Robinson building upon the tradition of richly detailed and imaginative book illustration that Tenniel had helped to establish. While their styles differed, the high standard of craftsmanship and the deep engagement with the text were hallmarks that Tenniel exemplified.

Sir John Tenniel remains a pivotal figure, an artist whose work was both a product of its time and timeless in its appeal. His meticulous skill, imaginative power, and the sheer volume and consistency of his output over a long career secure his place as one of the most important and influential illustrators and cartoonists in history. His images continue to be studied, admired, and enjoyed, a testament to their enduring artistic power and cultural significance.