John Neagle stands as a significant figure in the pantheon of early American artists, a portraitist whose canvases captured the burgeoning identity of a young nation. Active during the first half of the 19th century, Neagle's work provides a vivid pictorial record of the individuals who shaped Philadelphia and, by extension, the United States. His ability to combine technical proficiency with an insightful grasp of his sitters' characters established him as a leading painter of his time, leaving a legacy that continues to inform our understanding of American art and society in the antebellum period.

Early Life and Artistic Genesis

John Neagle was born in Boston, Massachusetts, on November 4, 1796. His birth in Boston was somewhat serendipitous, as his parents, Maurice Nagle (the artist later added the 'e') and Susannah Taylor, were residents of Philadelphia merely visiting the New England city at the time. This early connection to Philadelphia would prove formative, as the city would become the primary locus of his artistic career and personal life. His father was a native of Ireland, and his mother was from New Jersey, highlighting the diverse origins that characterized the young American republic.

Neagle's artistic inclinations manifested early, though his initial path into the art world was not one of straightforward academic training, which was less formalized in America compared to Europe. He was largely self-taught in his foundational years, a common trajectory for many American artists of that era. His formal artistic education began around the age of fifteen when he started to receive drawing lessons from Pietro Ancora, an Italian artist and drawing master who had settled in Philadelphia. Ancora, though perhaps not a towering figure himself, provided Neagle with essential foundational skills in draughtsmanship, a critical underpinning for any aspiring painter, especially a portraitist.

Following his studies with Ancora, Neagle was apprenticed to Thomas Wilson, a coach and ornamental painter. This apprenticeship, while not directly in fine art, was a common entry point for aspiring artists. It provided practical experience in handling paints, understanding color, and executing decorative work, skills that could be transferred to canvas painting. During this period, Neagle's ambition to become a portrait painter grew. Philadelphia, at the time, was a vibrant cultural and artistic center, second only perhaps to Boston in the nascent American art scene.

The Influence of Mentors and Masters

Crucially, during his time with Wilson, Neagle came into contact with more established figures in the Philadelphia art world. He encountered Bass Otis, a versatile artist known for portraits and historical scenes, who had also, interestingly, produced the first American lithograph. Otis likely provided encouragement and perhaps some informal guidance. However, a more significant influence was Thomas Sully, who would become an informal mentor and a lifelong friend. Sully, an English-born artist who had risen to become one of America's most fashionable and successful portrait painters, recognized Neagle's talent.

Sully's style, characterized by its fluid brushwork, elegant compositions, and often romanticized depictions, was heavily influenced by the British portrait tradition, particularly the work of Sir Thomas Lawrence. Neagle absorbed much from Sully, not only in terms of technique but also in understanding the business of portraiture and navigating the social circles from which commissions arose. The generosity of Sully in sharing his knowledge was instrumental in Neagle's development. Neagle would later marry Sully's stepdaughter, Mary Chester Sully, further cementing their personal and professional connection.

In 1825, seeking to broaden his artistic horizons and refine his skills, Neagle made a pivotal trip to Boston. There, he had the invaluable opportunity to meet and observe Gilbert Stuart, arguably the most celebrated American portraitist of the era, renowned for his iconic depictions of George Washington. Neagle spent about two months in Boston, during which he not only painted Stuart's portrait but also received advice and criticism from the elder master. Stuart's emphasis on capturing the character and "inner man" of the sitter, his direct and often unidealized approach, and his sophisticated handling of flesh tones, offered a counterpoint to Sully's more overtly romantic style. This encounter profoundly impacted Neagle, encouraging a greater psychological depth and robustness in his own work.

During this same Boston sojourn, Neagle also met Washington Allston, another leading figure in American art, known for his historical and literary paintings imbued with Romantic sensibility. While Allston's primary genre differed from Neagle's, exposure to an artist of Allston's intellectual and artistic caliber would have undoubtedly been stimulating, broadening Neagle's understanding of the broader artistic currents of the time. The combined influences of Sully's elegance and Stuart's directness, filtered through Neagle's own developing sensibility, helped forge his distinctive style. He also deeply admired the work of British masters like Sir Joshua Reynolds and Sir Henry Raeburn, whose portraits he would have known through engravings and possibly some originals that made their way to America.

Forging a Career in Philadelphia

By 1818, John Neagle had made the decisive commitment to pursue portraiture as his primary vocation. He established his own studio in Philadelphia, a city that offered a burgeoning market for portraits among its affluent merchants, professionals, and civic leaders. His early work began to attract attention, demonstrating a keen ability to capture a likeness while imbuing his subjects with a sense of presence and dignity. Philadelphia's elite, including doctors, lawyers, clergymen, and businessmen, increasingly sought out his services.

Neagle's approach was marked by a desire to convey not just the physical appearance of his sitters but also their personality and social standing. He often incorporated symbolic elements or attributes related to their profession or significant life experiences, a practice common in portraiture but one that Neagle employed with particular acuity. This added layers of meaning to his works, transforming them from mere likenesses into richer biographical statements. His brushwork became increasingly confident, capable of rendering both fine detail and broader, more expressive passages.

His reputation grew steadily through the 1820s. He was industrious and his output was considerable. The city of Philadelphia, with its strong Quaker roots and burgeoning industrial and commercial power, provided a fertile ground for a portraitist who could capture both the sobriety and the ambition of its leading citizens. Neagle's ability to connect with his sitters on a personal level also contributed to his success, allowing him to elicit the naturalism and character that became hallmarks of his best work.

Masterpiece: Pat Lyon at the Forge

The painting that unequivocally catapulted John Neagle to national prominence was Pat Lyon at the Forge, completed between 1826 and 1827, with a second version finished in 1829. This monumental work is widely considered a landmark in American art and a masterpiece of genre portraiture. The subject, Patrick Lyon, was a successful blacksmith and locksmith who commissioned Neagle to paint him not in the conventional attire of a gentleman, but as a working artisan in his smithy.

Lyon's story was compelling: he had been falsely accused and imprisoned for a bank robbery years earlier, due to his skill in making impenetrable locks for the very bank that was robbed while he was out of town. Though eventually exonerated, the experience left a lasting mark. He specifically requested to be depicted as a blacksmith, proud of his trade and his hard-won respectability, with the Walnut Street Gaol, the site of his unjust imprisonment, visible in the background through an archway.

Neagle rose to the challenge with extraordinary skill and insight. The painting depicts Lyon, muscular and clad in a leather apron, pausing from his labor, hammer in hand, beside his anvil. A young apprentice works the bellows in the background. The composition is dynamic, with strong diagonals and a dramatic use of chiaroscuro – the play of light and shadow – highlighting Lyon's powerful form and the glowing heat of the forge. Neagle masterfully rendered the textures of metal, wood, leather, and flesh, creating a scene of palpable realism.

More than just a portrait, Pat Lyon at the Forge is a powerful statement about the dignity of labor, American democratic ideals, and individual resilience. It broke from the aristocratic conventions of much contemporary portraiture, which typically favored idealized depictions of the wealthy and powerful in refined settings. By portraying Lyon as a proud, self-made artisan, Neagle celebrated the values of hard work and ingenuity that were increasingly central to the American identity. The painting was an immediate success, widely exhibited and praised for its originality, technical brilliance, and compelling narrative. It secured Neagle's place as one of the foremost painters in America and remains a cornerstone of collections like that of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

A Prolific Portraitist of His Era

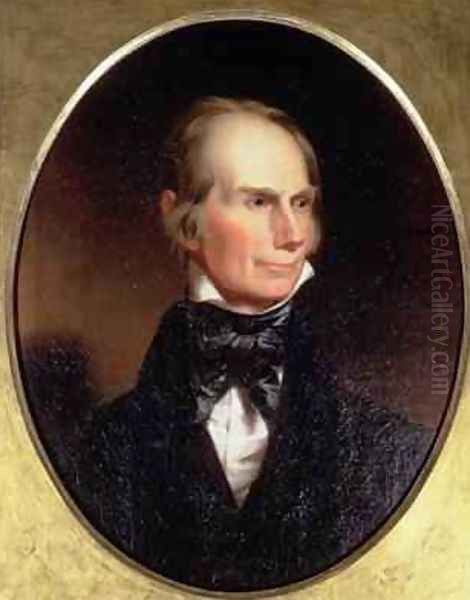

Following the triumph of Pat Lyon at the Forge, Neagle's services were in even greater demand. He continued to paint a wide array of individuals, creating a veritable gallery of early 19th-century American society. His sitters included prominent figures such as the statesman Henry Clay, whose portrait by Neagle captured the intellectual force and oratorical power for which "The Great Compromiser" was known. Another notable work is his portrait of Thomas Ustick Walter, the architect of the dome and wings of the U.S. Capitol, depicted with the tools and plans of his profession.

Neagle's portraits of fellow artists, such as his likeness of Gilbert Stuart, are particularly insightful, often revealing a shared understanding and a nuanced portrayal of creative individuals. He painted numerous physicians, lawyers, merchants, and clergymen, each rendered with an attention to individual character that transcended mere formula. While, like many portraitists of his day, his male portraits are often considered his strongest, showcasing a robust modeling and psychological acuity, he also painted many women and children. His portraits of women, while sometimes adhering more closely to prevailing conventions of feminine grace, could also display considerable character and sensitivity.

His style, while rooted in the Anglo-American tradition, evolved. The influence of Stuart encouraged a more direct and less idealized portrayal, while his admiration for British Romantics like Sir Thomas Lawrence informed his often rich color palettes and dynamic compositions. Neagle developed a remarkable ability to capture the textures of fabrics, the gleam of polished wood, and, most importantly, the subtle expressions that convey personality. He was adept at using pose and setting to further elucidate the sitter's identity and social role. His portraits were not just faces, but carefully constructed representations of individuals within their societal context.

Engagement with the Art Community

John Neagle was not an isolated artist but an active and influential member of Philadelphia's burgeoning art community. His commitment to advancing the cause of American art and supporting fellow artists was evident throughout his career. In 1821, he became one of the founding members of the Artists' Fund Society of Philadelphia, an organization established to provide financial assistance to artists in need and to promote American art through exhibitions. He served as its president for many years, from 1835 to 1844, demonstrating his leadership and dedication.

Furthermore, Neagle played a significant role in the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA), one of the oldest and most prestigious art institutions in the United States. He was elected a director of PAFA and served in that capacity, contributing to its governance and the development of its collections and exhibitions. His involvement with these institutions underscores his belief in the importance of a supportive infrastructure for the arts in America. PAFA, founded in 1805 by figures including Charles Willson Peale and sculptor William Rush, was crucial in providing exhibition opportunities and art education.

His interactions with contemporary artists were numerous. Beyond his formative relationships with Sully and Stuart, he maintained connections with many others. For instance, records indicate he visited the home of Thomas Birch, a notable marine and landscape painter, in Philadelphia during the winter of 1829. These interactions, whether formal or informal, created a network of shared knowledge and mutual support that was vital for the growth of a distinct American artistic tradition. Neagle, through his work and his institutional service, was a key figure in this development, helping to professionalize the role of the artist in American society.

Ventures Beyond Philadelphia

While Philadelphia remained his primary base and the source of his greatest success, John Neagle, like many artists of his time, sought to expand his professional opportunities by traveling to other cities. Portrait commissions could be lucrative, but the market in any single city, even one as large as Philadelphia, could become saturated or subject to changing tastes and economic conditions.

He made several trips to the American South and West. He spent time working in Lexington, Kentucky, a significant center in the westward expansion of the young nation. He also worked in New Orleans, Louisiana, a city with a unique cultural blend and considerable wealth derived from trade and agriculture. These journeys were undertaken with the hope of securing new patrons and broadening his reputation.

However, these ventures outside of Philadelphia met with mixed success. While he did receive commissions in these other locales, he never quite replicated the consistent acclaim and steady stream of work he enjoyed in his home city. The reasons for this are likely multifaceted. Establishing a reputation in a new city took time and required navigating different social networks. Moreover, other established or itinerant artists were also competing for patronage in these areas. Ultimately, Neagle's strongest connections and deepest roots remained in Philadelphia, and it was there that his career truly flourished. These excursions, nonetheless, provided him with a broader experience of American life and society, which may have subtly informed his artistic perspective.

Artistic Style and Technique Summarized

John Neagle's artistic style is best characterized by its robust realism, psychological insight, and technical assurance. He possessed a remarkable ability to capture not only a faithful physical likeness but also the intangible essence of his sitter's personality. This was achieved through careful observation and a nuanced understanding of human expression. His figures have a tangible presence, often appearing to engage directly with the viewer.

His brushwork was versatile, capable of meticulous detail in rendering faces and important attributes, while also employing broader, more fluid strokes in drapery and backgrounds. This created a pleasing balance between precision and painterly effect. His color palettes were typically rich and harmonious, with a particular skill in rendering flesh tones that possessed both warmth and verisimilitude, a skill likely honed by his study of Gilbert Stuart.

Compositionally, Neagle's portraits are generally well-structured and dynamic. He often used strong lighting, sometimes employing a dramatic chiaroscuro reminiscent of Baroque masters, as seen so effectively in Pat Lyon at the Forge. This use of light and shadow not only modeled form but also added to the psychological intensity of his portrayals. He was adept at integrating sitters with their environments, using props and settings to provide context and enhance the narrative dimension of the portrait. While influenced by the elegance of the British school, particularly through Thomas Sully and Sir Thomas Lawrence, Neagle's work often possessed a distinctly American directness and lack of artifice, especially in his male portraits.

Navigating the Art World: Controversies and Concerns

John Neagle's career was not without its share of engagement with the broader issues and occasional controversies of the art world. One notable instance involved the protection of artists' rights and intellectual property. He played a role in bringing attention to the unauthorized copying of Gilbert Stuart's famous "Lansdowne" portrait of George Washington. Neagle reported to William Dunlap – an artist and the first major chronicler of American art history – how a Philadelphia merchant had commissioned copies of the Lansdowne portrait from Stuart, then had additional, unauthorized copies made in England by an artist named Winstanley, thereby depriving Stuart of income and control over his work. This account became an important part of Dunlap's narrative on Stuart in his seminal 1834 book, A History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design in the United States, highlighting early concerns about copyright and artistic ownership.

Another minor issue that arose, common in the study of prolific artists, was that of attribution. A painting titled Miss Ryan was at one point attributed to Neagle, but this attribution was later questioned and ultimately retracted based on stylistic discrepancies and chronological inconsistencies. Such scholarly debates are part of the ongoing process of refining art historical knowledge.

Neagle also voiced concerns about the practical aspects of the art world, such as exhibition conditions. He is recorded as having complained about the overcrowding at exhibitions held by the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, noting that the sheer number of items displayed made it difficult for viewers to properly appreciate the form, color, or texture of individual works. This reflects a perennial concern among artists for their work to be seen to its best advantage, and it underscores Neagle's engagement with the practicalities of presenting art to the public.

Later Years and Legacy

John Neagle continued to paint actively through the 1840s and into the 1850s, though the peak of his fame and productivity was arguably in the 1820s and 1830s. Like many artists who experience a long career, he witnessed shifts in artistic taste and the rise of new generations of painters. The advent of photography in the mid-19th century also began to impact the market for painted portraits, offering a quicker and often cheaper means of capturing a likeness, though painted portraiture continued to hold prestige.

His health began to decline in his later years, which naturally affected his output. John Neagle passed away in Philadelphia on September 17, 1865, at the age of 69. He left behind a substantial body of work that serves as an invaluable record of his time and a testament to his skill as a portraitist.

His legacy is significant. He is recognized as one of the leading American portrait painters of the Jacksonian era, a period of significant social and political change in the United States. His ability to capture the character of a diverse range of individuals, from prominent statesmen to proud artisans, reflects the evolving democratic spirit of the nation. Works like Pat Lyon at the Forge remain iconic, celebrated not only for their artistic merit but also for their cultural significance.

Neagle in Art History: Evolving Perspectives

The art historical evaluation of John Neagle has evolved over time. During his lifetime and in the decades immediately following his death, he was highly regarded, particularly for his powerful male portraits and, of course, Pat Lyon at the Forge. His technical skill and his ability to convey character were widely acknowledged.

As with many artists from earlier periods, his reputation may have experienced some fluctuations as new artistic movements and critical perspectives emerged. In some early 20th-century assessments, there was a tendency to view his female portraits as perhaps less consistently strong or insightful than his male likenesses, possibly reflecting the differing societal expectations and conventions for portraying men and women at the time. However, a broader appreciation of his entire oeuvre has since developed.

Modern scholarship recognizes Neagle's important contributions to the development of American portraiture. He is seen as a key figure who successfully blended aspects of the refined British portrait tradition (as exemplified by artists like Sir Joshua Reynolds, Sir Thomas Lawrence, and his mentor Thomas Sully) with a more direct, robust, and characteristically American approach, partly influenced by Gilbert Stuart. His willingness to tackle unconventional subjects, like Pat Lyon in his working environment, demonstrated an innovative spirit.

His role in fostering the art community in Philadelphia, through his involvement with the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and the Artists' Fund Society, is also recognized as an important part of his contribution. He was not just a painter but also an institution builder, helping to create a more supportive environment for artists in America. Today, Neagle is firmly established in the canon of American art, valued for his skillful technique, his insightful portrayals, and the rich historical and cultural context his works provide. He is seen as a bridge figure, connecting the colonial portrait tradition of artists like John Singleton Copley and Charles Willson Peale to the more Romantic and individualized styles of the mid-19th century.

Collections and Enduring Presence

John Neagle's paintings are held in the collections of many major American museums, ensuring their continued visibility and study. The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, an institution with which he was closely associated, holds a significant collection of his works, including one version of Pat Lyon at the Forge and portraits such as William Crook Rudman Sr. (1845) and Levi Dickson (1834). The Athenaeum of Philadelphia, another historic institution in the city, houses his portrait of Thomas Ustick Walter.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, also possesses an important version of Pat Lyon at the Forge. Other institutions across the United States, including the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. (which holds some of his sketches), and various state historical societies and university art galleries, feature his portraits in their collections. His work has been included in numerous survey exhibitions of American art, and he has been the subject of focused scholarly attention.

Beyond his finished paintings, archival materials related to Neagle, such as his notebooks, account books, and printed ephemera, are preserved in institutions like the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Smithsonian Archives of American Art. These materials provide valuable insights into his working methods, his patrons, and the artistic milieu of his time. The continued presence of his works in public collections and their availability for scholarly research ensure that John Neagle remains an important and accessible figure for understanding the art and culture of early 19th-century America. His auction records, though perhaps not reaching the stratospheric heights of some later artists, reflect a consistent appreciation for his work among collectors of American art.

Conclusion

John Neagle's career spanned a transformative period in American history, and his art provides a compelling window into that era. From his early training and the crucial mentorship of figures like Thomas Sully and Gilbert Stuart, he forged a distinctive style characterized by psychological depth, technical skill, and a robust realism. His masterpiece, Pat Lyon at the Forge, remains a powerful emblem of American democratic ideals and the dignity of labor, securing his national reputation. As a prolific portraitist of Philadelphia's leading citizens and a dedicated contributor to its artistic institutions, Neagle played a vital role in shaping the cultural landscape of his time. His legacy endures through his numerous portraits, which continue to engage viewers and offer rich insights into the individuals and the society of antebellum America, solidifying his position as a pivotal artist in the nation's visual heritage.