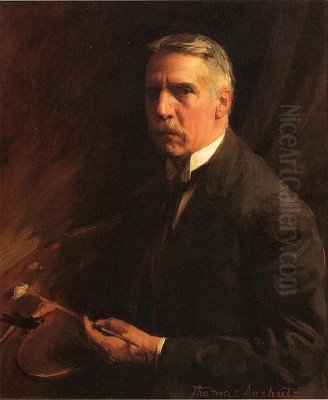

Thomas Pollock Anshutz (1851–1912) stands as a significant, if sometimes underappreciated, figure in the landscape of American art. Functioning as both a dedicated painter and an influential educator, Anshutz played a crucial role in the transition of American art at the turn of the 20th century. His career bridged the meticulous realism of his own mentor, Thomas Eakins, and the burgeoning modernism embraced by many of his students, including key members of the Ashcan School. Anshutz's legacy is thus twofold: a body of work characterized by thoughtful observation and technical skill, and an even more profound impact through the generations of artists he nurtured.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in Newport, Kentucky, on October 5, 1851, Thomas Anshutz spent his formative years in his birthplace and later in Wheeling, West Virginia, and Brooklyn, New York. These diverse environments likely exposed him to a variety of American life, which would later inform his artistic subjects. His initial formal art training commenced in 1872 at the National Academy of Design in New York City. There, he studied under Lemuel Wilmarth, an artist who himself had studied in Europe under Jean-Léon Gérôme, bringing a strong academic tradition to his teaching. This early grounding in academic principles would serve Anshutz well, providing a solid foundation for his later explorations.

The pivotal moment in Anshutz's artistic development, however, came in the autumn of 1876 when he enrolled at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) in Philadelphia. PAFA was, at that time, a hotbed of artistic innovation and rigorous training, largely due to the presence of Thomas Eakins, one of America's most formidable and controversial realist painters. Anshutz immersed himself in the academy's curriculum, focusing on drawing, painting, and, crucially, anatomy – a subject that Eakins championed with an almost scientific fervor.

The Enduring Influence of Thomas Eakins

At PAFA, Thomas Anshutz quickly distinguished himself, and by 1878, he had become Thomas Eakins's chief assistant. This close association with Eakins was profoundly formative. Eakins advocated for a direct, unvarnished approach to realism, emphasizing the importance of anatomical correctness, direct observation from life, and the study of photography as an aid to understanding form and motion. Anshutz absorbed these principles deeply, and they became hallmarks of his own artistic and pedagogical approach.

Eakins's tenure at PAFA was, however, fraught with controversy, particularly regarding his uncompromising use of nude models and his insistence on anatomical dissection. In 1886, following a dispute over the use of a fully nude male model in a class that included female students (the infamous "loincloth incident"), Eakins was forced to resign. Thomas Anshutz, his trusted protégé, was chosen to succeed him, first as an instructor and eventually, in 1909, as the head of the painting department. While Anshutz maintained Eakins's emphasis on anatomical study and rigorous drawing, his teaching style was generally considered less confrontational and perhaps more adaptable than his mentor's.

Parisian Studies and Broadening Perspectives

Like many ambitious American artists of his generation, Anshutz sought further refinement of his skills in Paris. He traveled to Europe in 1892, studying at the prestigious Académie Julian. There, he received instruction from noted academic painters such as Henri Lucien Doucet and William-Adolphe Bouguereau. While Bouguereau represented a highly polished, idealized form of academic art, the Parisian environment also exposed Anshutz to a wider range of artistic currents, including the lingering influences of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism.

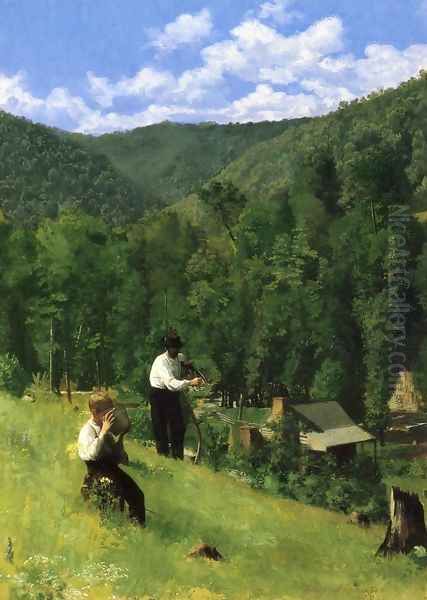

This European sojourn, though rooted in academic tradition, subtly broadened Anshutz's artistic palette. He became increasingly interested in the effects of light and color, particularly in outdoor settings. While he never fully embraced the broken brushwork of French Impressionism in the manner of artists like Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro, his later work, especially his watercolors and landscapes, often displays a brighter palette and a more nuanced sensitivity to atmospheric conditions. This period marked a gentle evolution in his style, integrating new influences without abandoning his foundational realist principles.

Anshutz the Painter: Style, Subject, and Major Works

Thomas Anshutz's oeuvre is characterized by its thoughtful realism, technical proficiency, and a quiet dignity in its portrayal of human subjects and their environments. His style, while rooted in Eakins's tradition, developed its own distinct characteristics, often displaying a greater interest in color and a less severe psychological intensity than his mentor's work.

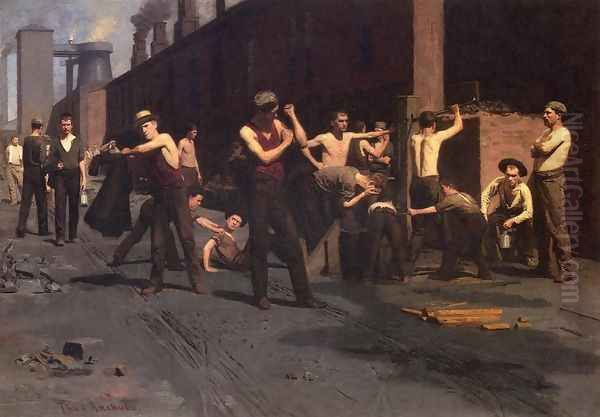

The Ironworkers' Noontime: A Landmark of Industrial Realism

Perhaps Anshutz's most famous painting is The Ironworkers' Noontime, completed around 1880-1881. This seminal work depicts a group of foundry workers taking their midday break in the factory yard in Wheeling, West Virginia. The painting is a powerful piece of American realism, notable for its unidealized depiction of industrial labor. Anshutz spent considerable time sketching and photographing the workers and the site, striving for accuracy in their poses, attire, and the grimy industrial setting.

The composition is complex, featuring over twenty figures in various states of repose – some washing, others stretching, some simply resting under the midday sun. The work captures a sense of camaraderie and shared experience among the men, but also the physical toll of their labor. The Ironworkers' Noontime is considered a pioneering work in the depiction of American industry and labor, predating much of the Ashcan School's focus on urban and working-class themes. It stands as a testament to Anshutz's commitment to observing and recording the realities of contemporary American life, much like Winslow Homer was doing with rural and maritime subjects.

Portraiture: Capturing Character and Presence

Anshutz was also a gifted portraitist. His portraits are marked by a keen observation of character and a solid, three-dimensional rendering of form. One of his most celebrated portraits is A Rose (1907), which depicts a young woman, Rebecca H. Whelen, in a thoughtful pose, holding a single pink rose. The painting combines the anatomical solidity inherited from Eakins with a softer, more atmospheric quality and a refined sense of color, particularly in the treatment of the sitter's dress and the subtle background. Critics have noted that works like A Rose demonstrate Anshutz's ability to blend Eakins's structural rigor with a painterly elegance reminiscent of contemporaries like John Singer Sargent, albeit with a more reserved demeanor.

Another notable example is his Portrait of a Philadelphia Gentleman. Throughout his career, Anshutz painted numerous portraits, often of colleagues, students, and prominent Philadelphians. These works consistently reveal his deep understanding of human anatomy and his ability to convey the sitter's personality without resorting to flattery or overt sentimentality. His anatomical painting, Standing academic male nude, Paris, further showcases his dedication to the human form, a direct result of his rigorous training and teaching.

Landscapes, Watercolors, and the Use of Photography

Beyond his major figure compositions and portraits, Anshutz was an avid landscape painter, particularly in watercolor. During summers, often spent at the Darby School of Painting which he co-founded, or on trips to locations like Holly Beach, New Jersey, or the Delaware River, he produced numerous fresh and luminous outdoor studies. These works often show a greater engagement with Impressionistic concerns of light and color. Works like Roofs, St. Cloud and Steamboat on the Ohio River demonstrate his versatility in capturing different environments.

Like Eakins, Anshutz recognized the value of photography as a tool for artists. He used the camera to capture fleeting moments, study anatomical details, and gather information for his paintings. This practice was not about slavishly copying photographs but rather about using them as a reference to enhance the realism and accuracy of his painted compositions. His photographic studies, particularly of figures in motion or in relaxed, unposed attitudes, informed works like The Ironworkers' Noontime.

Other significant works that illustrate his range include Their Way of Life, capturing genre scenes, and the tender Mother and Child (c. 1900), which shows a more impressionistic handling of paint and a focus on intimate domesticity.

Anshutz the Educator: A Profound and Lasting Legacy

While Thomas Anshutz's paintings are significant, his most enduring impact on American art may well be through his decades of teaching at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. He was a revered instructor, known for his dedication, his systematic approach to teaching anatomy and composition, and his ability to inspire his students.

Leadership at PAFA and Teaching Philosophy

After succeeding Eakins, Anshutz became a cornerstone of the PAFA faculty for over thirty years, eventually becoming Director of the painting department. His teaching philosophy, while grounded in Eakins's principles of direct observation and anatomical understanding, was perhaps more open to individual student expression. He continued the tradition of life classes, dissection (when available), and rigorous drawing, believing these were essential foundations for any artist. He famously used écorché figures (anatomical models with the skin removed to show musculature) to demonstrate the underlying structure of the human body.

Anshutz encouraged his students to find their own voices while insisting on a strong technical grounding. He was known for his insightful critiques and his patient guidance. His influence extended beyond the classroom; he was a mentor and a source of encouragement for many aspiring artists.

The Darby School of Painting

In 1898, Anshutz, along with fellow artist Hugh Breckenridge, co-founded the Darby School of Painting in Darby, Pennsylvania. This summer school offered students an opportunity for plein air (outdoor) painting, focusing on landscape and the figure in natural light. The Darby School provided a more relaxed, experimental environment compared to the formal academy setting, allowing Anshutz and his students to explore color theory and the effects of light more freely. This initiative demonstrates Anshutz's commitment to diverse modes of art education.

A Roster of Influential Students

The list of artists who studied with Thomas Anshutz reads like a who's who of early 20th-century American art. His students included:

Robert Henri: A charismatic painter and teacher who became the leading figure of the Ashcan School. Henri absorbed Anshutz's emphasis on depicting contemporary life but pushed it in a more expressive and urban-focused direction.

John Sloan: Another key member of the Ashcan School, known for his gritty and empathetic portrayals of New York City life.

William Glackens: Initially an illustrator, Glackens, under Anshutz's influence and later through exposure to French Impressionism (especially Renoir), developed a more colorful and painterly style.

George Luks: Known for his robust and energetic depictions of urban characters.

Everett Shinn: Famous for his scenes of theater and urban life, often with a dynamic, illustrative quality.

These five artists, along with Arthur B. Davies, Ernest Lawson, and Maurice Prendergast (who did not study with Anshutz but shared similar artistic aims), would later form "The Eight," a group that famously challenged the conservative exhibition policies of the National Academy of Design in 1908.

Beyond the core Ashcan group, Anshutz also taught:

Charles Demuth: A leading figure in American Modernism, known for his Precisionist style and delicate watercolors.

John Marin: Celebrated for his dynamic and semi-abstract watercolors of urban scenes and seascapes.

Charles Sheeler: Another pioneer of Precisionism, who, like Anshutz, effectively used photography in conjunction with his painting.

Arthur B. Carles: An important American modernist known for his vibrant color abstractions.

Margaret Taylor Fox: A talented painter who, like many female artists of the era, benefited from Anshutz's inclusive teaching.

Anshutz's ability to nurture such a diverse range of talents, from the urban realists of the Ashcan School to the avant-garde modernists, speaks volumes about his effectiveness as an educator. He provided them with essential skills and encouraged them to explore their own artistic paths.

An Unconventional Interest: Art, Anatomy, and Remedies

Anshutz's deep fascination with anatomy, inherited and expanded from Eakins, was central to his art and teaching. He believed that a thorough understanding of the body's structure was indispensable for any figure painter. This interest sometimes led him into areas that were considered sensitive at the time, such as the detailed study of nude figures, which, while essential for academic art, could still provoke controversy in socially conservative Philadelphia. His painting Standing academic male nude, Paris is a clear product of this rigorous anatomical focus.

A more peculiar manifestation of his wide-ranging interests was his involvement with traditional and alternative medicine. He reportedly contributed to or helped edit a book titled New, Old and Forgotten Remedies: Papers by Many Writers, which was published posthumously in 1917 (likely compiled from his notes or with his prior input by his relative, the homeopathic physician and publisher Edward P. Anshutz). This compendium included information on a variety of remedies, some conventional (like alfalfa and eucalyptus) and others quite unusual (such as gunpowder, dog's milk, and spider's venom). While seemingly far removed from his artistic pursuits, this interest perhaps reflects a broader intellectual curiosity and an empirical mindset, akin to the observational skills he applied to his painting.

Later Years and Artistic Evolution

Thomas Anshutz continued to teach at PAFA until shortly before his death. In his later years, his own painting style showed a continued, albeit subtle, evolution. His palette often became brighter, and his handling of paint somewhat looser, particularly in his landscapes and watercolors. He remained committed to realism but was not immune to the changing artistic climate. He exhibited his work regularly, though he never achieved the same level of public fame as some of his students. His primary focus remained on his teaching and the development of his own carefully considered art.

He also took on administrative roles, serving as a leader within PAFA and participating in the broader art community. For instance, he was invited to lecture at institutions like the New York School of Art (later Parsons), run for a time by William Merritt Chase, another prominent American artist and educator. Anshutz maintained friendships with many artists, including his former students like Robert Henri and modernists like Charles Demuth, indicating his respected position within diverse artistic circles.

Historical Significance and Enduring Legacy

Thomas Pollock Anshutz died on June 16, 1912, in Fort Washington, Pennsylvania, at the age of 60. His historical significance is multifaceted. As a painter, he created iconic images of American life, most notably The Ironworkers' Noontime, and a consistent body of high-quality portraits and landscapes. His work provides a vital link between the staunch realism of Thomas Eakins and the more socially engaged realism of the Ashcan School.

However, it is arguably as an educator that Anshutz's influence was most profound and far-reaching. He shaped a generation of American artists who would go on to define various movements in the early 20th century. His dedication to fundamental artistic principles, combined with an openness that allowed his students to flourish in diverse directions, marks him as one of America's most important art teachers. While Eakins laid a crucial foundation for American realism, Anshutz built upon it and, critically, transmitted its core values while allowing for adaptation and innovation.

For many years, Anshutz's own artistic achievements were somewhat overshadowed by those of his teacher and his more famous students. However, scholarly re-evaluation in the later 20th and early 21st centuries has led to a greater appreciation of his contributions as both an artist in his own right and a pivotal figure in the history of American art education. His work is now found in major American museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Conclusion

Thomas Pollock Anshutz was more than just a competent painter or a dedicated teacher; he was a crucial conduit for artistic ideas and practices during a period of significant change in American art. His commitment to realism, tempered by an appreciation for color and light, and his unwavering belief in the importance of anatomical understanding, provided a bedrock for his own art and the training he offered his students. Through his paintings, and even more so through the remarkable careers of those he taught, Anshutz left an indelible mark on the trajectory of American art, securing his place as a quiet but essential force in its development.