John Webber, a name inextricably linked with the Age of Exploration and the visual documentation of worlds previously unknown to Europe, stands as a significant figure in late 18th-century art. His work, born from direct observation during Captain James Cook's fateful third voyage, provided an invaluable pictorial record of the Pacific, its peoples, and its landscapes, forever shaping European perceptions. This article delves into the life, career, artistic style, and enduring legacy of this Swiss-English artist, whose canvases and drawings opened a window onto distant shores.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

John Webber was born in London in 1751 or 1752, the son of Abraham Wäber, a Swiss sculptor who had relocated to England. Despite his London birth, young John's formative years were spent in Bern, Switzerland, where he was sent at the age of six to be raised by an aunt. It was in Bern that his artistic inclinations were first nurtured. He received formal training under Johann Ludwig Aberli, a prominent Swiss landscape painter and engraver known for his picturesque views and pioneering use of colored outline etching. Aberli's influence likely instilled in Webber a keen eye for topographical detail and the nuances of landscape representation.

Seeking to broaden his artistic horizons, Webber traveled to Paris around 1770. There, he enrolled in the prestigious Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, immersing himself in the academic traditions of the time. He is also believed to have studied or worked closely with Jean-Georges Wille, a German engraver and art dealer based in Paris, who was highly regarded for his landscape drawings and prints. Wille's circle included many aspiring artists, and his emphasis on direct observation of nature would have resonated with Webber's earlier training. During his Parisian sojourn, Webber honed his skills in oil painting and figure drawing, preparing him for the diverse challenges that lay ahead.

A Return to London and a Fateful Appointment

In 1775, John Webber returned to London, eager to establish his career. He began exhibiting his work, and a painting shown at the Royal Academy in 1776 caught the attention of Dr. Daniel Solander. Solander, a Swedish botanist and an associate of Sir Joseph Banks, had sailed on Captain Cook's first voyage (1768-1771) alongside the artist Sydney Parkinson, who tragically died on the return journey. Understanding the immense value of visual records for such expeditions, Solander was instrumental in recommending Webber for the post of official artist on Cook's upcoming third voyage.

The Admiralty sought an artist capable of making accurate drawings and paintings of the places, peoples, flora, fauna, and cultural practices encountered. William Hodges had admirably fulfilled this role on Cook's second voyage (1772-1775), producing stunning atmospheric landscapes of the Pacific. Now, the mantle was to pass to Webber. His Swiss-Germanic training in precise landscape rendering, combined with his Parisian academic polish, made him a suitable candidate. In June 1776, John Webber was formally appointed, embarking on an adventure that would define his artistic legacy.

Charting New Worlds: The Artist at Sea

Aboard HMS Resolution, under the command of Captain James Cook, John Webber set sail in July 1776. His primary responsibility was to create a comprehensive visual ethnography and topography of the voyage. This was no small task. He was expected to produce "portraits of human figures, views of countries, trees, plants, fruits, birds, fishes, etc." – essentially, anything of scientific, anthropological, or geographical interest. His toolkit would have included pencils, watercolors, inks, and paper, materials that allowed for relatively quick sketching and coloring in the often-challenging conditions at sea or during brief landings.

The voyage took them across vast expanses of the Pacific Ocean. They visited the Kerguelen Islands (then known as Desolation Island), Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania), and New Zealand, where Cook had previously landed. They then sailed through the Tongan and Society Islands, including Tahiti, a place already familiar to Europeans through the accounts and art from Cook's earlier voyages, notably the work of Parkinson and Hodges. Webber's task was to build upon these records, offering fresh perspectives and more detailed observations.

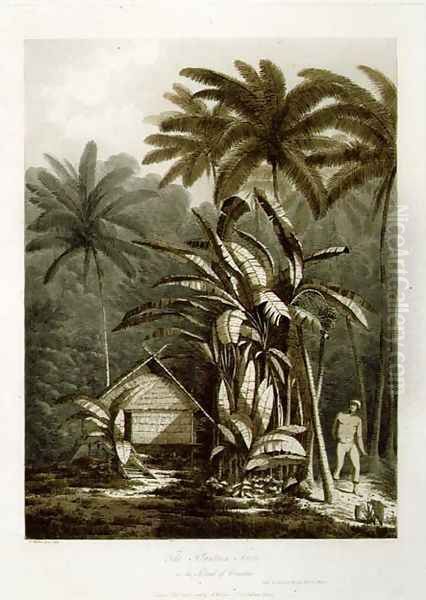

Webber’s artistic output during these initial stages was prolific. He meticulously documented landscapes, coastal profiles crucial for navigation, and the unique attire, adornments, and daily activities of the indigenous populations. His depictions of Tahitian dances, ceremonies, and domestic scenes provided Europeans with vivid insights into a culture that was both fascinating and profoundly different from their own. He often worked rapidly, capturing the essence of a scene or a likeness before the opportunity passed.

Encounters in the North Pacific: Hawaii and Nootka Sound

A significant phase of the voyage involved exploration of the North Pacific. In early 1778, Cook's expedition became the first group of Europeans to make formal contact with the Hawaiian Islands, which Cook named the Sandwich Islands. Webber was thus privileged to be among the first European artists to depict the Hawaiian people and their environment. His portraits of Hawaiian aliʻi (chiefs) and commoners, their feathered cloaks and helmets, their impressive double-hulled canoes, and their unique heiau (temples) are of immense historical importance. Works such as "A Man of the Sandwich Islands, Dancing" or views of Kealakekua Bay capture the initial, relatively peaceful interactions.

Later that year, the expedition sailed north along the western coast of North America, searching for the elusive Northwest Passage. They anchored in Nootka Sound, off present-day Vancouver Island, Canada. Here, Webber documented the Mowachaht/Muchalaht people, part of the Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations. His drawings and paintings of their distinctive wooden longhouses, totem poles, elaborate masks, and whaling practices are among the earliest visual records of these cultures. "A Woman of Nootka Sound" and "Interior of a Habitation at Nootka Sound" showcase his attention to ethnographic detail, from clothing to domestic arrangements.

The expedition continued to Alaskan waters, charting the coastline and encountering various Inuit and Aleut communities. Webber’s visual record extended to these northern climes, capturing the stark landscapes and the resilience of the people inhabiting them. His work provided a visual counterpoint to the often-dry official logs and journals, bringing the narratives to life.

The Tragic Climax: The Death of Captain Cook

The expedition returned to the Hawaiian Islands in late 1778 for reprovisioning. Tensions, however, began to escalate between the crew and the Hawaiians. On February 14, 1779, at Kealakekua Bay, a confrontation over a stolen cutter led to violence, and Captain James Cook was killed. John Webber was present during these tragic events, though likely not at the immediate site of Cook's death. He would later create several versions of this pivotal moment, the most famous being "The Death of Captain Cook."

This dramatic composition, which became one of the most iconic images of the 18th century, was carefully constructed to convey the chaos and tragedy of the event. While it takes some artistic liberties for dramatic effect, as many historical paintings of the era did (compare with Benjamin West's "The Death of General Wolfe"), it remains a powerful and enduring representation. Webber’s eyewitness status lent his depiction a particular authority, and it was widely disseminated through engravings, profoundly influencing the popular imagination regarding Cook's demise and the character of Pacific encounters.

After Cook's death, Captain Charles Clerke took command, and the expedition made another attempt to find the Northwest Passage before turning south. Clerke himself died of tuberculosis off the coast of Kamchatka, where Webber also sketched the landscape and local people. Lieutenant John Gore then assumed command for the final leg of the journey back to England, arriving in October 1780.

Return to England: Acclaim and Legacy

Upon his return to England, John Webber found himself a figure of considerable interest. The sketches and paintings he brought back were eagerly anticipated, offering a visual feast from the farthest reaches of the globe. His immediate task was to prepare his artworks for engraving to illustrate the official account of the voyage, "A Voyage to the Pacific Ocean," published in 1784. Webber personally supervised the engraving process, working with skilled craftsmen like Francesco Bartolozzi and William Woollett to ensure the fidelity of the prints to his original drawings. Sixty-one of his drawings were engraved for this publication.

Beyond the official account, Webber also capitalized on the public's fascination with the Pacific by publishing his own sets of prints. Between 1788 and 1792, he issued a series of aquatints titled "Views in the South Seas," which further showcased his artistry and the exotic locales he had visited. These prints, often hand-colored, were popular and helped to solidify his reputation.

Webber continued to exhibit at the Royal Academy, where his Pacific subjects garnered significant attention. His unique experiences and the novelty of his subject matter set him apart from many of his contemporaries, such as the landscape painters Richard Wilson or Thomas Gainsborough, or the portraitist Sir Joshua Reynolds, then President of the Royal Academy. In 1785, he was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA), and in 1791, he achieved the distinction of becoming a full Royal Academician (RA), a testament to his standing in the British art world. Other notable Royal Academicians of the period included Philippe Jacques de Loutherbourg, known for his dramatic landscapes and seascapes, and Joseph Wright of Derby, famed for his scientific and industrial scenes.

Webber's Artistic Style and Techniques

John Webber's style was characterized by a blend of topographical accuracy and picturesque sensibility, typical of late 18th-century British landscape art. His training under Aberli would have emphasized careful observation and detailed rendering of landscapes, a skill essential for his role on Cook's voyage. His watercolors are particularly noteworthy for their clarity, delicate washes, and attention to detail. He was adept at capturing the specific qualities of light and atmosphere in diverse environments, from the tropical brilliance of Tahiti to the misty shores of Alaska.

In his figure studies and portraits, Webber aimed for a degree of ethnographic accuracy, carefully recording clothing, ornamentation, and physiognomy. Works like his portrait of "Poedua," the daughter of a Tahitian chief, demonstrate a sensitivity and an attempt to capture individual character, though always framed within the European artistic conventions of the time. It's important to acknowledge that while his work was documentary in intent, it was inevitably filtered through a European lens, sometimes romanticizing or "othering" his subjects.

Compared to William Hodges, the artist on Cook's second voyage, Webber's style is often seen as more linear and less painterly. Hodges was renowned for his innovative use of color and light to convey atmospheric effects, sometimes at the expense of precise detail. Webber, while also capable of capturing atmosphere, generally placed a greater emphasis on clear delineation and factual representation, which was perhaps more aligned with the scientific objectives of the Admiralty. His work provided a bridge between the purely scientific illustration of someone like Sydney Parkinson and the more romanticized landscape traditions.

Later Years and Enduring Influence

After the flurry of activity related to publishing his voyage art, Webber continued to paint and exhibit. He undertook sketching tours in Britain, producing landscapes of Derbyshire and Wales, demonstrating his versatility beyond exotic subjects. However, his fame remained primarily attached to his Pacific works. He never married and lived a relatively quiet life in London.

John Webber died on April 29, 1793, at the relatively young age of 41 or 42. He left behind a remarkable body of work that has proven invaluable to art historians, anthropologists, and historians of exploration. His drawings and paintings are held in major collections worldwide, including the British Museum, the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, the Dixson Galleries of the State Library of New South Wales, the Peabody Essex Museum, and the Honolulu Museum of Art.

Webber's contribution extends beyond the purely artistic. His images provided crucial data for ethnographers and anthropologists studying the cultures of the Pacific as they existed at the point of sustained European contact. While subject to the biases and perspectives of his time, his work offers a unique and irreplaceable visual record. He, along with artists like Parkinson and Hodges, helped to create a new genre of "voyage art" that combined scientific documentation with aesthetic appeal, profoundly influencing how Europeans visualized and understood the wider world. His legacy is that of an artist who not only possessed considerable skill but was also in the right place at the right time, using his talents to document a pivotal moment in global history. His depictions of Pacific life, landscapes, and the dramatic events of Cook's final voyage continue to fascinate and inform us to this day.