Introduction: An Artist of Two Worlds

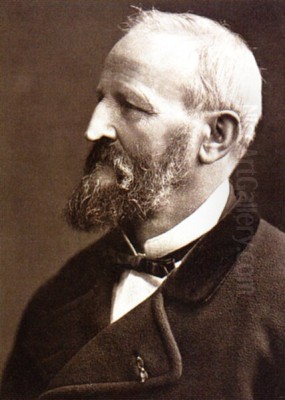

Johann Carl Bodmer, known widely as Karl Bodmer, stands as a significant figure in 19th-century art, bridging the worlds of ethnographic documentation and European landscape painting. Born in Zurich, Switzerland, on February 11, 1809, his life journey took him from the picturesque landscapes of the Rhine Valley to the rugged, then largely unknown territories of the North American interior, and finally to the artistic heart of France. He passed away in Paris on October 30, 1893, leaving behind a legacy defined by meticulous observation and artistic skill.

Bodmer's fame rests primarily on the extraordinary body of work he produced during his participation in the expedition led by the German naturalist Prince Maximilian of Wied-Neuwied to the upper Missouri River from 1832 to 1834. As the official artist for this scientific venture, Bodmer created hundreds of watercolors and sketches that provide an unparalleled visual record of the Plains Native American cultures and the landscapes they inhabited, just before catastrophic changes swept through the region. Later in his career, he became associated with the Barbizon School in France, shifting his focus to forest scenes and animal studies, yet always retaining his characteristic precision.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Karl Bodmer's artistic inclinations emerged early. He received initial training from his uncle, Johann Jakob Meier, a painter and engraver who specialized in landscapes and vedute (detailed topographical views). This early exposure instilled in Bodmer a strong foundation in drawing and watercolor techniques, emphasizing accuracy and detail – qualities that would become hallmarks of his later work. As a young man, Bodmer traveled extensively along the Rhine, Moselle, and Lahn rivers in Germany.

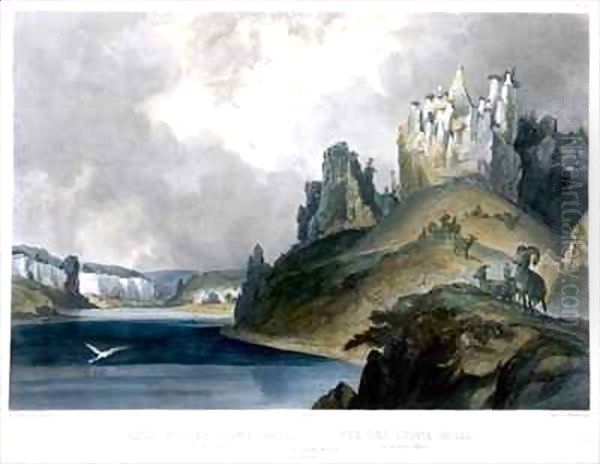

During these formative years, Bodmer honed his skills by creating picturesque views of towns, castles, and river landscapes, often intended for the growing tourist market. These works, typically watercolors and aquatints, demonstrated his burgeoning talent for capturing both architectural detail and atmospheric effects. This period was crucial in developing the technical proficiency and observational discipline that Prince Maximilian would later seek for his ambitious North American expedition. Bodmer learned to work efficiently outdoors, capturing the essence of a place with both speed and precision.

The Defining Expedition: Journey to the Interior of North America

The pivotal moment in Bodmer's career arrived in 1832 when he was hired by Prince Maximilian of Wied-Neuwied. Maximilian, an experienced explorer and trained naturalist, was planning a major scientific expedition to the interior of North America, specifically focusing on the flora, fauna, and indigenous peoples along the Missouri River. Having previously explored Brazil, Maximilian understood the vital importance of accurate visual documentation and sought an artist capable of producing scientifically valuable illustrations. The 23-year-old Bodmer, recommended for his skill and detailed style, accepted the challenging commission.

The expedition set sail for America, arriving in Boston before traveling overland to St. Louis, the gateway to the western frontier. In the spring of 1833, Bodmer, Maximilian, and their party boarded the American Fur Company steamboat Yellow Stone to begin their arduous journey up the Missouri River. Their travels took them deep into territories inhabited by numerous Native American tribes, including the Omaha, Ponca, Sioux (Lakota), Arikara, Mandan, Hidatsa, and the powerful Blackfoot Confederacy. The journey was fraught with difficulties, including harsh weather, disease, mechanical failures on the steamboats, and the underlying tensions of the frontier.

Maximilian’s journals and Bodmer’s art document the challenges faced. They navigated treacherous river conditions, endured extreme temperatures, and witnessed the precariousness of life on the Plains. One particularly harrowing experience recorded by Maximilian, and likely witnessed by Bodmer, occurred in August 1833 near Fort McKenzie in present-day Montana. An attack on a Piegan Blackfeet camp by a large war party of Assiniboine and Cree warriors resulted in significant bloodshed, a stark reminder of the dangers inherent in the region. Bodmer's role required him to work under these often-difficult conditions, capturing fleeting moments and complex scenes with remarkable composure.

Artistic Mission on the Missouri

Bodmer's mandate from Prince Maximilian was clear: to create a comprehensive and accurate visual record of everything they encountered. This included detailed landscapes showing the geological formations and distinctive features of the Missouri River Valley, precise renderings of newly documented plants and animals, and, most importantly, sensitive and detailed portrayals of the Native American peoples they met. Maximilian, with his scientific background, emphasized objectivity and accuracy, qualities Bodmer possessed in abundance.

Over the course of the 28-month expedition, Bodmer produced an astonishing portfolio of over 400 watercolors and sketches. He meticulously documented the appearance, attire, dwellings, tools, weapons, ceremonies, and daily activities of the various tribes. His portraits captured the individuality and dignity of his subjects, ranging from influential chiefs and warriors to women and children. He depicted intricate beadwork, feather adornments, painted robes, ceremonial pipes, and specific hairstyles with ethnographic precision. His landscapes captured the vastness and unique beauty of the Plains and the dramatic formations of the Upper Missouri Breaks.

Bodmer’s working method often involved making quick sketches on the spot, sometimes adding color notes, and then developing these into more finished watercolors later, often back at their forts or encampments. He worked primarily in watercolor, a medium well-suited to capturing subtle tones and details, but also employed pencil and ink. The sheer volume and consistent quality of his output under challenging field conditions attest to his dedication, skill, and physical endurance. He was not merely illustrating the journey; he was co-creating a vital scientific and cultural document.

Masterworks of Observation: The Portraits and Scenes

Among Bodmer's most celebrated works are his portraits of Native American individuals. His depiction of Mató-Tópe (Four Bears), a Mandan chief, is iconic. Bodmer painted him multiple times, capturing his elaborate war bonnet, painted shirt depicting his battle exploits, and dignified bearing. These portraits are rendered with such detail that they serve as invaluable records of Mandan regalia and personal history. Another striking work is Péhriska-Rúhpa (Moennitarri Warrior in the Costume of the Dog Dance), showing a Hidatsa man in the full, dramatic costume of the Dog Society, complete with a massive headdress of raven and magpie feathers trailing to the ground.

Bodmer also excelled at capturing group scenes and cultural practices. His image Bison-Dance of the Mandan Indians provides a dynamic view of a crucial ceremony performed to call the buffalo herds. It depicts the dancers wearing buffalo masks inside a Mandan earth lodge, conveying the energy and spiritual significance of the event. His landscapes, such as View of the Stone Walls on the Upper Missouri, showcase the unique geological formations of the region with a clarity that borders on the scientific, yet possess a distinct atmospheric quality.

The artistic style evident in these works is characterized by its meticulous realism and fine detail. Bodmer employed precise draftsmanship, delicate watercolor washes, and often used gum arabic to enrich colors and add depth. While adhering to the demands of accuracy, his compositions are often aesthetically compelling, demonstrating a keen eye for balance and visual interest. His work provides a stark, invaluable contrast to the more romanticized or generalized depictions of Native Americans common at the time.

Comparison with Contemporaries: Bodmer and Catlin

When discussing artists who documented Native American life in the 1830s, Karl Bodmer is inevitably compared to his American contemporary, George Catlin. Catlin traveled extensively in the West during the same period, often visiting the same tribes, including the Mandan and Hidatsa. Both artists aimed to record cultures they believed were vanishing, but their approaches and styles differed significantly.

Catlin was arguably more prolific, producing a vast "Indian Gallery" of hundreds of portraits and scenes, often painted quickly in oil. His style is generally broader and more painterly than Bodmer's, sometimes capturing a powerful immediacy but occasionally sacrificing detail for effect. Catlin was also more of a showman and self-promoter, touring his gallery extensively in the US and Europe. Bodmer, working under the scientific direction of Maximilian, focused on meticulous detail and ethnographic accuracy, rendered primarily in watercolor and later translated into highly refined aquatints. His output was smaller but arguably more detailed and technically sophisticated.

While both artists provide invaluable records, Bodmer's work is often favored by anthropologists and historians for its precision in depicting material culture. Other artists were also active in the West around this time or shortly after. Alfred Jacob Miller traveled the Oregon Trail in 1837 with Sir William Drummond Stewart, creating romanticized watercolor sketches of Plains life and the Rocky Mountains, stylistically quite different from Bodmer's realism. Seth Eastman, a U.S. Army officer, created detailed drawings and paintings of Sioux and Ojibwe life in the Upper Mississippi region, sharing Bodmer's eye for accuracy but often within a military context. Artists like John Mix Stanley and the Canadian painter Paul Kane also contributed significantly to the visual record of Western tribes later in the 19th century.

The Publication of Travels in the Interior of North America

Upon returning to Europe in 1834, Bodmer and Maximilian began the monumental task of preparing Maximilian's journals and Bodmer's illustrations for publication. This resulted in the landmark work, Reise in das innere Nord-America in den Jahren 1832 bis 1834 (Travels in the Interior of North America, 1832–1834), published in several parts between 1839 and 1843. Bodmer moved to Paris to oversee the production of the accompanying atlas of illustrations, which involved translating his delicate watercolors into high-quality prints.

The atlas volume contained 81 aquatint engravings based on Bodmer's field studies. Aquatint was a complex intaglio printmaking process capable of rendering tonal gradations similar to watercolor washes. Bodmer worked closely with talented Parisian engravers, such as Paul Legrand and Eugène Desmadryl, to ensure the fidelity of the prints to his original works. Many of the plates were exquisitely hand-colored, further enhancing their beauty and accuracy. The publication was a major undertaking and a significant expense for Maximilian.

The resulting book and atlas were acclaimed for their scientific value and artistic merit. Published simultaneously in German, French, and English editions, they introduced European audiences to the Plains Native American cultures and the landscapes of the American interior with unprecedented detail and accuracy. Bodmer's images became the definitive visual representation of these subjects for decades, profoundly shaping European understanding and imagination of the American West. The publication cemented Bodmer's reputation as a first-rate topographical and ethnographic artist.

Later Career: Barbizon and Beyond

After the intense period of work on the Travels publication, Bodmer remained in France, eventually settling in the village of Barbizon, southeast of Paris, around 1849. Barbizon was becoming the center of a new movement in French landscape painting, known as the Barbizon School. Artists like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Jean-François Millet, Théodore Rousseau, and Charles-François Daubigny gathered there, rejecting the idealized landscapes of Neoclassicism in favor of a more direct, realistic depiction of nature, often painted outdoors (en plein air).

Bodmer became associated with this group, shifting his artistic focus primarily to landscapes, particularly scenes of the Forest of Fontainebleau, and detailed studies of animals. His meticulous style, honed during the American expedition, adapted well to the Barbizon ethos of close observation of nature. He produced numerous paintings, drawings, etchings, and even experimented with photography later in life. His forest interiors and depictions of deer and other wildlife were well-regarded.

He continued to exhibit his work regularly at the prestigious Paris Salon, achieving recognition for his Barbizon paintings as well as occasionally exhibiting works derived from his American journey. In 1863, three of his watercolors based on the Missouri expedition were awarded a second-class medal at the Salon. His contributions were further acknowledged when he was named a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour in 1877. Though his Barbizon work is perhaps less famous than his American portfolio, it represents a significant phase of his long career, connecting him to major trends in French Realism. His detailed yet atmospheric landscapes offer an interesting comparison to the broader, more light-focused approaches of contemporaries like Corot or the sublime, dramatic landscapes of artists like J.M.W. Turner in England.

Artistic Style Revisited: Precision and Realism

Across his long career, the defining characteristic of Karl Bodmer's art remained his commitment to precision and realism. Whether depicting the intricate beadwork on a Mandan shirt, the geological strata of a Missouri bluff, or the texture of bark in the Forest of Fontainebleau, Bodmer's eye missed little. His draftsmanship was consistently strong, providing a solid structure for his delicate applications of color, primarily in watercolor during his American period and often in oil during his Barbizon years.

His American work, guided by Maximilian's scientific objectives, exemplifies empirical observation. It largely avoids the overt romanticism or dramatic narrative seen in the work of some contemporaries, such as the heroic or exotic scenes favored by French Romantics like Eugène Delacroix. Bodmer's focus was on documenting the visual facts, yet his work transcends mere illustration through its technical finesse and compositional skill. The clarity and detail provide an invaluable ethnographic record, capturing cultural practices and material objects with an accuracy that remains highly prized.

In his later Barbizon work, while still grounded in realism, there is perhaps a greater emphasis on atmosphere and the play of light within the forest settings. However, the underlying meticulousness remains. His animal studies, in particular, showcase his continued dedication to accurate anatomical representation combined with an ability to capture the creature's natural posture and environment. Bodmer's realism was less about social commentary (as seen in Millet's peasant scenes) and more about the faithful rendering of the natural world.

Controversies and Critical Perspectives

While Bodmer's work is widely celebrated for its historical and artistic value, contemporary scholarship sometimes examines it through a more critical lens. Like many European depictions of non-European peoples in the 19th century, his work can be analyzed within the context of colonialism and the "imperial gaze." Some critics argue that despite the intended objectivity, the perspective is inherently that of an outsider, potentially framing Native American cultures according to European preconceptions or emphasizing aspects deemed exotic or picturesque.

The very act of documenting cultures perceived as "vanishing" can be seen as problematic, potentially contributing to narratives that naturalized colonial expansion. Furthermore, while Bodmer captured the visual details of ceremonies and daily life, his images alone cannot fully convey the complex social, spiritual, and political contexts from the perspective of the Native peoples themselves. Modern exhibitions, such as a notable one at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, have sought to address these issues by incorporating Indigenous voices and perspectives alongside Bodmer's images, offering a more nuanced understanding.

However, it is crucial to balance these critiques with the undeniable value of Bodmer's work. Compared to many other contemporary representations, his images are remarkably respectful and detailed. For many of the Plains tribes he depicted, particularly the Mandan and Hidatsa who suffered devastating smallpox epidemics shortly after his visit, Bodmer's work constitutes one of the most important, and in some cases only, visual records of their traditional way of life from that specific period. Many Native communities today value these images as precious links to their heritage.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Karl Bodmer's legacy is substantial and multifaceted. His most significant contribution remains the visual documentation of the peoples and landscapes of the Upper Missouri River in 1833-1834. These images provide an irreplaceable resource for anthropologists, historians, and art historians studying the American West and Native American cultures. Their accuracy in depicting clothing, artifacts, architecture, and ceremonies is unmatched for the period. The original watercolors, primarily housed at the Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, Nebraska, and the aquatints, found in collections like the Newberry Library in Chicago, are treasured cultural artifacts.

His work influenced the perception of the American West in Europe and America for generations. While later artists like Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell would depict the West with more action and drama, Bodmer's work stands as a benchmark for ethnographic detail. His association with the Barbizon School also secures his place within the history of 19th-century French landscape painting.

Beyond academia, Bodmer's images continue to resonate. They are frequently reproduced in books and documentaries about the American West and Native American history. Exhibitions of his work draw significant public interest, offering viewers a vivid window onto a past world. For the descendants of the people Bodmer depicted, his portraits and scenes are more than just historical documents; they are powerful connections to their ancestors and cultural traditions, consulted and cherished by tribal historians and community members.

Conclusion: A Legacy in Detail

Karl Bodmer's artistic journey was remarkable, spanning continents and artistic movements. From his early training in the Swiss-German tradition of detailed landscape to his defining role as visual chronicler of Prince Maximilian's expedition across the American Plains, and his later integration into the French Barbizon School, Bodmer consistently demonstrated exceptional technical skill and a profound commitment to observational accuracy.

His work along the Missouri River remains his most enduring legacy – a collection of images unparalleled in their detail and ethnographic significance, capturing a pivotal moment in the history of the American West and its Indigenous peoples. While subject to ongoing critical interpretation, the artistic quality and historical importance of Bodmer's American portfolio are undeniable. Combined with his later contributions to landscape and animal painting in France, Karl Bodmer emerges as a unique and important figure in the art history of the 19th century, an artist whose meticulous eye preserved worlds that were rapidly changing.