George Wesley Bellows stands as a monumental figure in the landscape of early 20th-century American art. An artist of immense energy and keen observation, he captured the dynamism, grit, and burgeoning identity of the United States during a period of profound transformation. Primarily associated with the Ashcan School and the broader movement of American Realism, Bellows created a body of work—spanning painting and lithography—that remains celebrated for its technical prowess, visceral impact, and unflinching portrayal of modern urban life. His canvases pulse with the energy of New York City streets, the brutal ballet of the boxing ring, and the quiet dignity of portraiture, securing his place as one of the most important and distinctly American artists of his time.

Early Life and the Call of Art

Born in Columbus, Ohio, in 1882, George Wesley Bellows initially seemed destined for a different path. Growing up in a Methodist, middle-class family, he displayed early artistic inclinations but truly excelled in athletics during his youth. He was a standout baseball and basketball player, demonstrating remarkable talent that extended beyond casual play. While attending Ohio State University from 1901 to 1904, he continued to pursue both sports and art, contributing illustrations to the university's yearbook, the Makio.

His athletic abilities were so pronounced that he received offers to play professional baseball, including a notable invitation from the Cincinnati Reds. However, the lure of the art world proved stronger. Bellows made the pivotal decision to forgo a potential career in professional sports, choosing instead to dedicate himself fully to artistic pursuits. This choice marked a significant turning point, leading him away from the Midwest and towards the vibrant, chaotic, and artistically fertile environment of New York City in 1904, just before completing his degree.

New York and the Influence of Robert Henri

Upon arriving in New York, Bellows enrolled at the New York School of Art (formerly the Chase School). There, he encountered the charismatic teacher and painter Robert Henri, a figure who would become arguably the most significant influence on his artistic development. Henri was a leading proponent of a new American realism, urging his students to abandon academic conventions and genteel subjects in favor of depicting the raw, unvarnished reality of contemporary urban life. He encouraged direct observation, bold brushwork, and finding beauty and significance in the everyday experiences of ordinary people.

Bellows quickly absorbed Henri's teachings and philosophy. Henri recognized Bellows's exceptional talent, drive, and innate understanding of composition and form. He became a mentor and a lifelong friend, fostering Bellows's confidence and guiding his focus. Bellows later referred to Henri as "my father in art," acknowledging the profound impact Henri had on shaping his artistic vision and encouraging him to find his subjects in the teeming streets, bustling docks, and crowded tenements of the city.

The Ashcan School and Urban Realism

Through his association with Henri, Bellows became closely aligned with the group of artists informally known as the Ashcan School. While not a formal movement with a manifesto, these artists shared a common interest in portraying the grittier aspects of New York City life, often focusing on working-class neighborhoods, immigrant communities, and scenes of leisure and labor that were previously considered unworthy of serious artistic attention. Key figures associated with this tendency, besides Henri and Bellows, included John Sloan, William Glackens, Everett Shinn, and George Luks.

These artists, along with Arthur B. Davies, Maurice Prendergast, and Ernest Lawson, had earlier formed the group known as "The Eight," who exhibited together in 1908 in protest against the conservative exhibition policies of the National Academy of Design. Bellows, though younger, shared their rebellious spirit and commitment to depicting contemporary American reality. His work from this period exemplifies the Ashcan ethos: capturing the fleeting moments, the energy, and the often harsh truths of the modern metropolis with immediacy and vigor.

Capturing the Pulse of the City

Bellows's early New York paintings are characterized by their dynamic compositions, vigorous brushwork, and keen sense of observation. He was drawn to the city's constant motion and its human drama. Works like Forty-two Kids (1907), depicting boys swimming and diving off a dilapidated pier on the East River, showcase his ability to capture youthful energy and the unglamorous side of urban recreation. The painting is notable for its frankness and lack of sentimentality, presenting the scene with an almost reportorial directness, yet imbued with painterly richness.

Another significant work, Men of the Docks (1912), portrays a group of longshoremen gathered on a cold winter day, waiting for work against the backdrop of a massive ocean liner and the Brooklyn waterfront. The painting conveys a sense of solidarity and quiet endurance among the workers, while also capturing the bleak, industrial atmosphere of the docks. Bellows uses a somber palette and strong, blocky forms to emphasize the weight and gravity of the scene, reflecting the often-precarious existence of the urban working class. His painting New York (1911) offers a broader, bustling view of city life, a vibrant tapestry of crowds, horse-drawn carriages, and early automobiles navigating the chaotic streets, showcasing his skill in handling complex, multi-figure compositions.

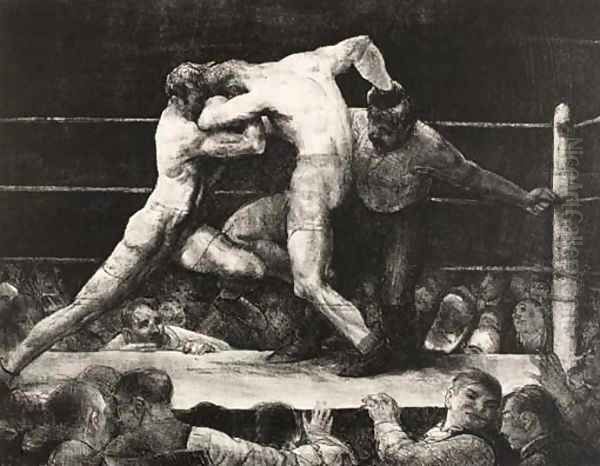

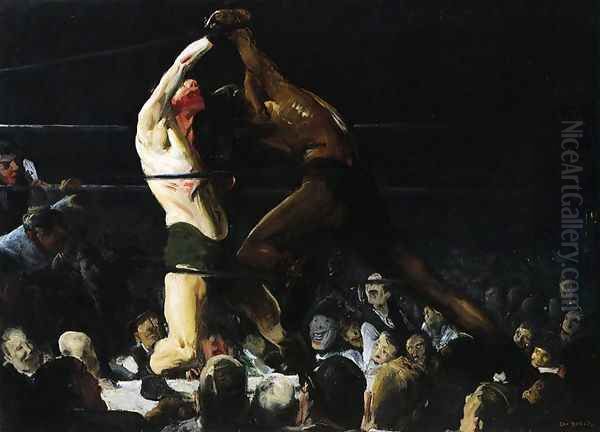

The Brutal Ballet: Bellows and the Boxing Ring

Among Bellows's most famous and powerful works are his depictions of illegal prize fights, which took place in private clubs to circumvent public boxing bans. These paintings capture the raw violence, intense physicality, and charged atmosphere of the underground boxing scene. Stag at Sharkey's (1909) is perhaps his most iconic work in this genre. Set in Tom Sharkey's Athletic Club, a dimly lit space crowded with onlookers, the painting freezes the moment of intense combat between two fighters. Bellows uses dramatic lighting, slashing brushstrokes, and contorted figures to convey the brutal energy and almost primal nature of the fight.

Both Members of This Club (1909), another celebrated boxing painting, pushes the intensity even further. It depicts a savage bout, possibly between a white and a black fighter (a controversial subject at the time), emphasizing the frenetic movement and the almost grotesque physicality of the struggle. The surrounding crowd leans in, their faces a mixture of excitement and bloodlust, making the viewer feel like a participant in the spectacle. These works were not merely depictions of sport; they were explorations of masculinity, violence, social class, and the spectacle of modern urban entertainment. Bellows's ability to render the human form in motion with such force and accuracy was remarkable.

The Armory Show and Encounters with Modernism

In 1913, Bellows played a role in organizing the landmark International Exhibition of Modern Art, better known as the Armory Show. This exhibition was a pivotal event in American art history, introducing large audiences in New York, Chicago, and Boston to the radical developments of European avant-garde art. Works by artists like Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Marcel Duchamp, Constantin Brancusi, and Wassily Kandinsky shocked and challenged American viewers and artists alike.

Bellows exhibited several of his own works in the show, and his paintings were generally well-received, representing a robust, distinctly American form of modern realism. While the Armory Show exposed Bellows and his contemporaries to Cubism, Fauvism, and other European innovations, Bellows's own style did not undergo a radical transformation towards abstraction. He remained largely committed to representational art, though he did experiment more consciously with color theory and compositional structure in subsequent years, perhaps partly influenced by the show's impact. His involvement underscored his position within the progressive wing of American art at the time.

Expanding Horizons: Landscapes and Portraits

While best known for his urban scenes and boxing paintings, Bellows was also a gifted landscape painter and portraitist. He spent summers away from the city, particularly on Monhegan Island in Maine and later in Woodstock, New York, where he captured the rugged beauty of the natural world. His seascapes, such as Blackhead and Sea (related to his later lithograph), often convey the power and drama of the ocean with the same energy he brought to his urban subjects, using bold colors and expressive brushwork. His landscapes explored the interplay of light, atmosphere, and geological forms.

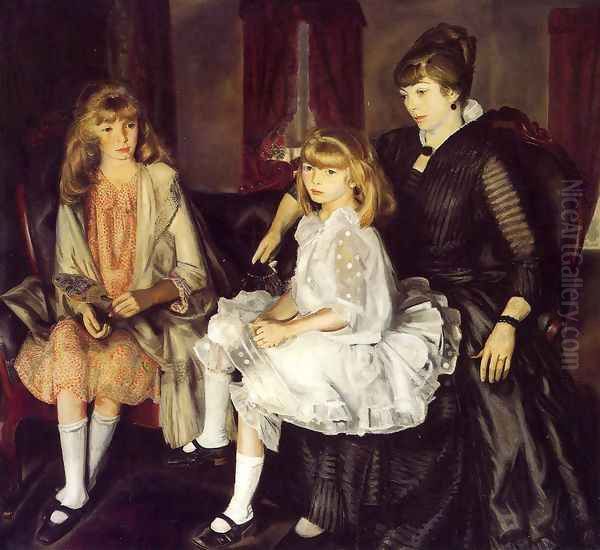

Bellows also produced numerous portraits throughout his career, often depicting family members, friends, and prominent figures. His portraits are characterized by their psychological insight and directness, avoiding flattery in favor of capturing the sitter's personality. Notable examples include portraits of his wife, Emma, and their daughters, Anne and Jean. Works like Emma and Her Children (1915) show a tender, yet unsentimental, portrayal of domestic life. He also undertook commissioned portraits, applying his vigorous style to more formal subjects. His approach to portraiture shares an affinity with the realism of earlier American masters like Thomas Eakins and Winslow Homer.

Mastery of Lithography

Around 1916, Bellows took up lithography with enthusiasm, quickly mastering the medium and elevating it as a serious art form in America. Working closely with master printers like Bolton Brown and George C. Miller, he produced nearly two hundred lithographs over the next decade. Printmaking offered him a different means of expression, allowing for stark tonal contrasts and linear precision. He revisited many of his earlier themes in lithography, including boxing scenes like A Stag at Sharkey's (1917), urban life, and landscapes.

His involvement in lithography coincided with World War I. Although he did not serve in the military, Bellows produced a series of powerful and harrowing lithographs depicting alleged German atrocities in Belgium, based on the Bryce Report. These prints, such as The Germans Arrive (1918), were intended as propaganda to support the Allied cause. While effective and technically brilliant, they drew criticism both then and later for their graphic violence and reliance on second-hand accounts. Bellows famously retorted to critics who questioned him painting scenes he hadn't witnessed, "I don't think Leonardo had a ticket to the Last Supper!" This series remains a controversial but significant part of his oeuvre, demonstrating his engagement with contemporary events and his skill in the lithographic medium. His dedication to printmaking helped revitalize the medium in the United States.

Social Commentary and Activism

Like many artists associated with the Ashcan School, Bellows held progressive social views, though his political engagement was complex. He contributed illustrations to the socialist magazine The Masses, alongside artists like John Sloan and Art Young. His drawings often depicted social inequalities, labor struggles, and the vibrancy of working-class life, aligning with the magazine's radical political stance.

However, Bellows was not dogmatically aligned with any single political ideology. His primary commitment was to depicting life as he saw it, with all its energy, contradictions, and injustices. His art often carried implicit social commentary through its choice of subjects—the harsh lives of dockworkers, the chaotic energy of tenement districts, the brutal spectacle of prize fights—rather than overt political messaging, with the notable exception of his WWI prints. His work reflected a deep empathy for his subjects and a critical eye towards the social structures of his time.

Later Years and Evolving Techniques

In the later years of his relatively short career, Bellows continued to explore new artistic avenues. He became interested in theories of color and composition, particularly Jay Hambidge's theory of "Dynamic Symmetry," which proposed mathematical principles underlying classical art and natural forms. He also experimented with the Maratta color system, a set of pre-mixed paints designed to ensure harmonious color relationships. These theoretical interests sometimes led to more structured and deliberately composed works in his later period, although his fundamental commitment to realism and vigorous execution remained.

He continued to paint landscapes, portraits, and genre scenes, maintaining a high level of productivity and critical acclaim. Had he lived longer, it is fascinating to speculate how his style might have further evolved, perhaps integrating more elements of modernism or developing his theoretical interests more fully. His work from the early 1920s, such as the portrait Annie (1923) or the theatrical House of Death: Punchinello (1923), shows his continued versatility and exploration.

A Sudden End and Enduring Legacy

George Bellows's prolific career was tragically cut short. In January 1925, he died suddenly from peritonitis resulting from a ruptured appendix. He was only 42 years old. His premature death was a significant loss to the American art world, silencing a voice that had powerfully captured the spirit of its age. At the time of his death, he was widely regarded as one of America's leading artists, celebrated for his technical skill, his uniquely American subject matter, and the sheer vitality of his work.

In the decades following his death, Bellows's reputation has remained strong. He is consistently recognized as a key figure in American Realism and the Ashcan School. His paintings and lithographs are held in major museum collections across the United States and internationally, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Whitney Museum of American Art. Retrospectives of his work continue to draw large audiences, reaffirming his importance.

Bellows's legacy lies in his ability to forge a powerful, modern, and distinctly American art from the fabric of everyday life. He bridged the gap between 19th-century realists like Eakins and Homer and later 20th-century painters such as Edward Hopper, who also found profound meaning in the American scene. Unlike some of his contemporaries who embraced European abstraction, Bellows demonstrated that realism could still be a vital and relevant mode of expression for the modern era. His work continues to resonate for its energy, its honesty, and its enduring depiction of the American experience in the early twentieth century. He remains, as one critic noted shortly after his death, one of the "most acclaimed American artists of his generation."

Conclusion: An American Original

George Wesley Bellows carved a unique and indelible path through American art history. From his decisive turn away from athletics towards art, through his immersion in the gritty realities of New York City under the guidance of Robert Henri, to his mastery of both painting and lithography, Bellows consistently produced work that was bold, dynamic, and deeply engaged with its time. His depictions of urban life, the visceral energy of the boxing ring, the ruggedness of the American landscape, and the character of its people cemented his reputation. Though his life was cut short, the power and vitality captured in his art ensure his enduring significance as a chronicler of American life and a master of modern realism. His work stands as a testament to the vibrant, complex, and rapidly changing nation he portrayed with such skill and passion.