Léon Herbo stands as a significant figure in late 19th-century Belgian art. Born in Templeuve, Hainaut, Belgium, on October 7, 1850, and passing away in Ixelles, Brussels, on June 19, 1907, Herbo carved a distinct niche for himself primarily as a painter of portraits, particularly celebrated for his refined and often idealized depictions of women. His career unfolded during a dynamic period in Belgian art, bridging the established academic traditions with the rise of Realism and the stirrings of modernism. He was not only a prolific artist but also an active participant in the artistic life of Brussels, co-founding an influential art circle and contributing to the education of future artists.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Herbo's artistic journey began not far from his birthplace. He initially pursued studies at the Academy of Fine Arts in Tournai, a respected institution that provided him with foundational skills. Seeking more advanced training, he moved to the heart of Belgium's art world, Brussels, enrolling at the prestigious Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts. This institution was a bastion of academic tradition, emphasizing rigorous drawing, composition, and the study of Old Masters.

In Brussels, Herbo had the opportunity to study under notable figures, including Joseph Stallaert (1825-1903). Stallaert was a prominent history painter and a key proponent of the academic style, known for his large-scale historical and allegorical compositions. Studying under Stallaert would have instilled in Herbo a strong command of technique, anatomy, and classical composition, elements that remained visible even as he developed his own Realist-inflected style. In 1869, Herbo demonstrated early promise by achieving a preliminary qualification for the prestigious Prix de Rome, a highly competitive award that offered winners the chance to study in Italy.

Broadening Horizons: Travels and Influences

Like many aspiring artists of his generation, Herbo understood the importance of travel for artistic development. After completing his formal studies in Brussels, he embarked on journeys to further refine his craft and broaden his perspectives. His travels took him to neighbouring France, the artistic epicentre of Europe, where he would have encountered the latest trends, including Realism as championed by Gustave Courbet and the burgeoning Impressionist movement.

He also spent time in Germany and Italy. Italy, in particular, offered the chance to study Renaissance and Baroque masterpieces firsthand, reinforcing the classical foundations of his training. These experiences abroad exposed Herbo to a wider range of artistic approaches and subject matter, enriching his visual vocabulary. Ultimately, however, he chose to establish his career back in Belgium, settling permanently in Brussels, which remained the centre of his professional life.

Debut and Establishing a Reputation

Herbo made his official debut in the Brussels art scene in 1875, exhibiting his work at the Brussels Salon. The Salons were crucial platforms for artists to gain visibility, attract patrons, and measure themselves against their peers. Herbo quickly began to build a reputation, particularly for his skill in portraiture. His ability to capture not only a physical likeness but also a sense of the sitter's personality and social standing resonated with the bourgeois clientele of the era.

His portraits were characterized by meticulous attention to detail, a smooth, polished finish, and a certain elegance that became his hallmark. He excelled at rendering textures – the sheen of silk, the softness of velvet, the intricate patterns of lace – which added to the luxurious feel of his paintings. While grounded in Realism's accurate observation, his work often imbued subjects, especially female ones, with an air of idealized grace and charm.

The Essence of Herbo's Art: Portraiture and Feminine Grace

The core of Léon Herbo's oeuvre lies in portraiture, and within that genre, he demonstrated a particular affinity for depicting women. His female portraits range from formal commissions of society ladies to more intimate, sometimes allegorical or character studies. He seemed fascinated by capturing the nuances of feminine beauty, elegance, and psychology as perceived through the lens of late 19th-century sensibilities.

His style blended the precise rendering learned through academic training with a Realist's focus on contemporary life and appearance. Unlike the starker social realism of artists like Charles Hermans (1839-1924), Herbo's realism was tempered with refinement. His brushwork was typically smooth and controlled, avoiding the visible, broken strokes associated with Impressionism. He paid great attention to costume, accessories, and setting, using these elements to enhance the sitter's status and character.

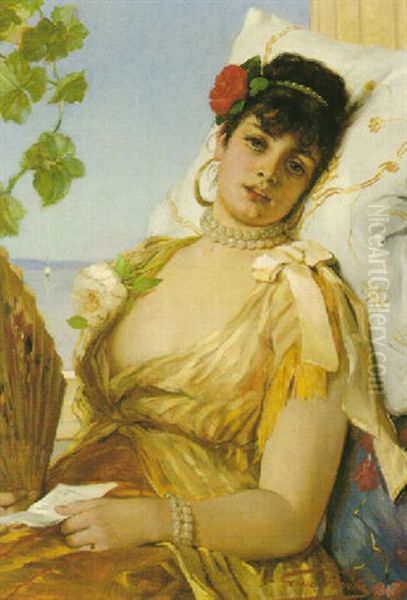

A quintessential example of his work in this vein is La Charmeuse (The Charmer). This painting embodies many qualities associated with Herbo: a beautifully rendered female figure, elegantly attired, exuding a quiet confidence and allure. The meticulous detail in the fabric, the delicate handling of light and shadow, and the subject's engaging gaze are characteristic of his approach. Works like this cemented his reputation as a master of depicting feminine grace, though some contemporary critics occasionally found his portrayals verging on the overly sensual or idealized, reflecting the era's complex attitudes towards representations of women.

Beyond Portraiture: Genre Scenes and Orientalism

While best known for portraits, Herbo's artistic interests extended to other genres. He produced genre scenes, often depicting moments of everyday bourgeois life or leisure. An example like Femme à la pêche (Woman Fishing) showcases his ability to capture tranquil, anecdotal moments with the same attention to detail and pleasing composition found in his portraits. These works offered glimpses into the pastimes and social customs of his time.

Herbo also explored Orientalist themes, a popular genre in 19th-century European art. Inspired by romanticized visions of North Africa and the Middle East, artists created scenes featuring exotic costumes, settings, and figures. Works such as Oriental Woman with Fruits and Flowers place Herbo within this trend. His teacher in Brussels, Joseph Stallaert, had travelled, and another influential Belgian figure, Jean-François Portaels (1818-1895), was a leading Orientalist painter and teacher whose work likely influenced many Brussels artists, including Herbo. Herbo's Orientalist paintings often feature beautifully dressed figures in opulent interiors, emphasizing decorative elements and an air of mystique.

Additionally, Herbo occasionally tackled religious or historical subjects, such as his painting Salome with the head of Saint John the Baptist. This work demonstrates his ability to engage with traditional themes, interpreting them through his characteristic style, focusing on the dramatic potential and the rendering of the figures and their attire, perhaps drawing inspiration from the grand history paintings of masters like Louis Gallait (1810-1887).

L'Essor: A Collective Endeavor for Realism

Léon Herbo was not merely an individual practitioner; he was also actively involved in the collective artistic life of Brussels. In 1876, he became one of the founding members of the Cercle Artistique et Littéraire known as 'L'Essor' (meaning 'The Flight' or 'The Rise'). He established this group alongside the sculptor Julien Dillens (1849-1904) and the painter Emile Namur. L'Essor emerged as a reaction against the perceived conservatism of the official Salons and aimed to provide younger artists, particularly those working in Realist modes, with more opportunities to exhibit their work.

L'Essor advocated for Realism but maintained a relatively open stance, allowing members considerable stylistic freedom. It became an important venue in Brussels, organizing regular exhibitions that showcased a diverse range of artists. While distinct from the more radical avant-garde group 'Les XX' (Les Vingt), founded later in 1883 by Octave Maus, L'Essor played a crucial role in promoting contemporary art in Belgium. Early on, artists who would later become key figures in Les XX, such as James Ensor (1860-1949) and Fernand Khnopff (1858-1921), exhibited with L'Essor before moving towards more progressive styles like Symbolism and Neo-Impressionism, the latter championed within Les XX by artists like Théo van Rysselberghe (1862-1926). Herbo remained associated with L'Essor, which represented a significant, if more moderate, force for artistic renewal.

Recognition, Awards, and Academic Role

Herbo's talent and dedication brought him considerable recognition during his lifetime. He regularly participated in major exhibitions not only in Brussels but also internationally. A significant moment came at the Exposition Universelle held in Paris in 1889, a landmark event showcasing global achievements in industry and culture. At this prestigious exhibition, Herbo received an Honorable Mention for his work, a testament to his standing beyond Belgium's borders.

Further honours followed. He was awarded the Knight's Cross of the Order of Leopold, a significant Belgian national honour, recognizing his contributions to the arts. Beyond his painting practice, Herbo also dedicated himself to teaching. He served as a professor at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, the very institution where he had trained. In this role, he would have passed on his technical expertise and artistic principles to a new generation of Belgian artists, contributing to the continuity of skill and tradition within the Brussels art scene. His position as a professor underscored his respected status within the artistic establishment.

Contextualizing Herbo: Contemporaries and Comparisons

To fully appreciate Léon Herbo's place in art history, it is helpful to view him alongside his contemporaries. He worked during a period of rich artistic diversity in Belgium. His polished Realism can be compared to that of Alfred Stevens (1823-1906), another Belgian painter highly successful in Paris, known for his elegant depictions of fashionable women in luxurious interiors, though Stevens often incorporated more narrative or psychological elements.

Compared to the social realism of Charles Hermans, whose large canvases sometimes depicted the struggles or realities of working-class life, Herbo's focus remained largely on the refinement and comfort of the bourgeoisie. Jan Verhas (1834-1896) was another contemporary known for his charming depictions of bourgeois children and beach scenes, sharing Herbo's commitment to detailed realism but focusing on different aspects of contemporary life.

Herbo's work stands in contrast to the emerging avant-garde movements that gained momentum during his career. While he exhibited alongside early modernists like James Ensor in the context of L'Essor, Herbo's style did not embrace the radical experimentation with form, colour, and subject matter seen in Ensor's later expressive and often grotesque works, or the decadent Symbolism of Félicien Rops (1833-1898), or the pointillist technique adopted by Théo van Rysselberghe. Herbo remained largely faithful to a more accessible, aesthetically pleasing form of Realism rooted in academic skill. His connection to Orientalism links him to figures like Portaels, while his academic background connects him to Stallaert and the tradition represented by older masters like Gallait.

Later Life, Legacy, and Collections

Léon Herbo continued to paint and teach in Brussels throughout the later years of his career. He remained a respected figure, known for his consistent style and technical proficiency. His death in Ixelles, a municipality of Brussels, in 1907 marked the end of a productive and successful career that spanned several decades of significant artistic change in Belgium.

Herbo's legacy rests primarily on his contribution to Belgian portraiture and his role within the L'Essor group. He masterfully captured the elegance and aspirations of the Belgian bourgeoisie in the late 19th century. His paintings are valued for their technical skill, their detailed rendering of costume and setting, and their often charming portrayal of feminine beauty. While perhaps not as revolutionary as some of his avant-garde contemporaries, Herbo represents a significant strand of Belgian Realism, one that emphasized refinement and aesthetic appeal.

Today, Léon Herbo's works can be found in various public and private collections. The Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels hold examples of his paintings, offering visitors a chance to see his work within the broader context of Belgian art history. The Musée des Beaux-Arts in his hometown of Tournai also preserves works by the artist. Many of his portraits, particularly those commissioned privately, remain in family collections or appear periodically on the art market, where they continue to be appreciated for their elegance and historical value. His painting Mannenportret (Portrait of a Man) from 1885, for instance, has appeared in auctions, indicating continued collector interest.

Conclusion: An Enduring Appeal

Léon Herbo occupies a specific and important place in the narrative of 19th-century Belgian art. As a highly skilled portraitist, he chronicled the appearance and ideals of his society with elegance and precision. His specialization in depicting women, rendered with a smooth finish and meticulous attention to detail, secured his popularity among patrons and critics of his time. His involvement in founding L'Essor highlights his commitment to fostering a supportive environment for artists working within the Realist tradition. While the artistic currents eventually flowed towards more radical forms of expression, Herbo's work endures as a fine example of polished Realism and refined portraiture, offering valuable insights into the aesthetic tastes and social milieu of late 19th-century Belgium. His paintings continue to charm viewers with their technical mastery and graceful subjects.