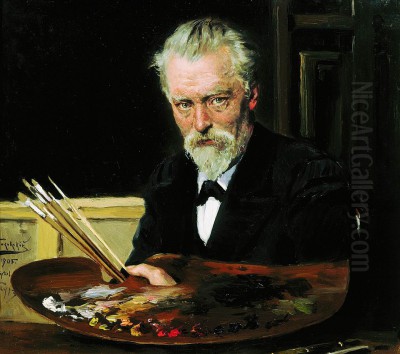

Vladimir Egorovich Makovsky stands as a significant figure in the landscape of 19th and early 20th-century Russian art. Born in Moscow on January 26, 1846, and passing away in Petrograd (now St. Petersburg) on February 21, 1920, Makovsky dedicated his life to capturing the multifaceted reality of Russian society through the lens of Realism. He was not merely a painter but also an influential educator and an active participant in the pivotal art movements of his time, most notably the Peredvizhniki (the Wanderers or Itinerants). His works, often imbued with gentle humor, sharp satire, and deep empathy, offer invaluable insights into the lives of ordinary Russians, making him a visual counterpart to the great realist writers of his era.

Artistic Heritage and Early Training

Vladimir Makovsky was born into a family deeply immersed in the arts. His father, Yegor Ivanovich Makovsky, was a notable figure in Moscow's cultural life, an amateur artist himself, and one of the founders of the prestigious Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture (MSPSA). This environment undoubtedly nurtured Vladimir's artistic inclinations from a young age. He grew up alongside his siblings, who also pursued artistic careers: Konstantin Makovsky, who became famous for his large-scale historical canvases and society portraits, and Nikolai Makovsky, another painter.

Surrounded by art and artists, Vladimir's path seemed preordained. At the age of fifteen, in 1861, he formally enrolled at the MSPSA, the very institution his father helped establish. There, he honed his skills under the tutelage of respected artists such as Evgraf Sorokin and Sergey Zaryanko. His talent was recognized early on; he received silver medals for his student work in 1865 and 1866, signaling his promise as a painter. This rigorous academic training provided him with a strong foundation in drawing and composition, which would serve him throughout his career.

The Peredvizhniki Movement and Makovsky's Rise

Makovsky's career coincided with a transformative period in Russian art, marked by the rise of the Peredvizhniki. Officially known as the Society for Travelling Art Exhibitions, this group emerged in the 1870s as a reaction against the perceived conservatism and elitism of the Imperial Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg. The Peredvizhniki sought to create an art that was distinctly Russian, accessible to a wider public, and engaged with contemporary social issues. They organized travelling exhibitions across Russia, bringing art directly to the provinces.

Vladimir Makovsky became a vital member of this movement, joining the Society in 1872. He fully embraced its ideals, focusing his artistic attention on genre scenes – depictions of everyday life. Unlike his brother Konstantin, who often painted grand historical narratives or idealized portraits, Vladimir turned his gaze towards the common folk: peasants, city dwellers, merchants, clerks, and the intelligentsia. He shared this commitment with fellow Peredvizhniki such as Ivan Kramskoi, the intellectual leader of the group, the landscape masters Ivan Shishkin and Alexei Savrasov, the powerful social commentator Vasily Perov, and the epic historical painters Ilya Repin and Vasily Surikov. Makovsky quickly became one of the leading figures within the movement, serving on its board and contributing significantly to its exhibitions.

Themes of Everyday Life: Humor and Social Observation

Makovsky's strength lay in his ability to observe and depict the nuances of human interaction and the fabric of Russian society. His early works often displayed a lighthearted, humorous touch, capturing amusing situations and character types. Paintings like The Grape-juice Seller (1879), Preserving Jam (also known as Fruit Preservation, 1876), and The Congratulator (1878) exemplify this aspect of his art. These works are characterized by their detailed settings, expressive figures, and gentle satire, often poking fun at human foibles without resorting to harsh caricature. They reveal the artist's keen eye for the small comedies and dramas unfolding in marketplaces, homes, and taverns.

His work often drew comparisons to the great Russian realist writers of the time. Critics noted parallels between Makovsky's visual narratives and the stories of Nikolai Gogol, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Leo Tolstoy, and Anton Chekhov. Like these literary giants, Makovsky explored the complexities of the Russian soul, the dynamics of social hierarchy, and the conditions of life for various strata of society. He even created illustrations for works by Gogol and Dostoevsky, further cementing this connection. His paintings tell stories, inviting viewers to contemplate the characters' circumstances and motivations.

Deepening Social Critique

As his career progressed, Makovsky's work often took on a more serious and critical tone, reflecting the growing social tensions and political unrest in late Imperial Russia. While humor remained an element, it was frequently employed to underscore deeper societal problems – poverty, bureaucratic indifference, the chasm between the rich and the poor, and the consequences of social upheaval. He moved beyond simple observation to offer poignant commentary on the human condition within the specific context of his time.

Several of his most acclaimed works belong to this period of heightened social awareness. In the Ante-room of the Court of Conciliation (1880) presents a cross-section of society awaiting justice, highlighting the anxieties and power dynamics at play within the bureaucratic system. The Collapse of the Bank (1881) vividly portrays the panic and despair of ordinary citizens losing their savings, a direct response to contemporary financial crises. The Released Prisoner (1882) is a powerful psychological study, capturing the complex emotions of a man returning to his family after incarceration, hinting at the social stigma and difficult readjustment faced by former convicts. These paintings are considered masterpieces of Russian critical realism.

Another significant work, The Benefactor, explores the theme of charity and the often-condescending attitudes of the wealthy towards the poor. Later paintings, such as On the Boulevard (1888) and You Shall Not Go (1892), continued to explore urban life and intimate family dramas, sometimes with a more somber, psychologically intense mood, reflecting perhaps the darkening atmosphere of the pre-revolutionary era. These works demonstrate his sustained engagement with the social and moral questions confronting Russian society.

Recognition and Academic Career

Makovsky's talent and dedication earned him significant recognition both within Russia and internationally. His painting The Nightingale Fanciers (1872-1873), an early genre scene depicting enthusiasts listening intently to a caged bird, was highly praised and earned him the prestigious title of Academician from the Imperial Academy of Arts in 1873. This work was also successfully exhibited in Vienna, contributing to his growing reputation.

Beyond his success as a painter, Makovsky made substantial contributions as an educator. He began teaching at his alma mater, the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture, in 1882, remaining there until 1894. His reputation as both an artist and a teacher led to his appointment as a professor at the Imperial Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg in 1893. He quickly rose through the ranks, serving as the Rector (head) of the Academy from 1894 to 1896. In these roles, he influenced a generation of Russian artists, upholding the principles of realism while guiding students in mastering their craft. His contemporaries at the Academy and in the broader art scene included figures like Valentin Serov and Isaac Levitan, both masters who, like Makovsky, navigated the currents of realism and impressionism. Other major figures of the era, such as Viktor Vasnetsov and Mikhail Nesterov, explored different facets of Russian identity through historical and spiritual themes, enriching the artistic dialogue of the time.

Later Life and Personal Aspects

Despite his artistic success and academic positions, Vladimir Makovsky reportedly did not achieve the same level of financial prosperity as his brother Konstantin, whose more flamboyant style and subject matter often appealed to wealthier patrons. Vladimir remained committed to his chosen path of depicting everyday life, a genre that, while critically acclaimed, was not always as lucrative. He was known to be a prolific artist, creating an estimated one thousand paintings over his lifetime.

In his personal life, Makovsky was married to Anna Gerasimova, and they had a son and a daughter. His family life sometimes provided inspiration for his genre scenes. Beyond painting, he was known to be an art collector, reflecting his deep engagement with the art world. An interesting anecdote reveals another facet of his personality: his love for music. He reportedly owned and played an expensive violin made by the renowned Italian luthier Guarneri, using music as a means of relaxation.

While widely respected, Makovsky occasionally faced criticism. Some contemporaries felt his work, particularly later in his career, sometimes lacked the passionate fire of younger artists or that he became too comfortable, focusing perhaps more on the material aspects of his success. However, such criticisms do little to diminish the overall significance of his contribution. He spent his later years primarily in St. Petersburg (renamed Petrograd in 1914), continuing to paint and remain involved in the art world until his death in 1920, shortly after the tumultuous events of the Russian Revolution.

Legacy

Vladimir Egorovich Makovsky left an indelible mark on Russian art. As a leading member of the Peredvizhniki, he played a crucial role in establishing Realism as the dominant force in Russian painting during the latter half of the 19th century. His vast body of work provides a rich, detailed, and empathetic panorama of Russian life across different social strata. He captured the spirit of his time – its humor, its sorrows, its social injustices, and its everyday realities – with remarkable skill and insight.

His paintings continue to be celebrated for their narrative power, psychological depth, and masterful technique. They are housed in major museums, including the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow and the State Russian Museum in St. Petersburg, where they remain popular with audiences. Through his dual roles as a prolific painter and a dedicated educator, Makovsky significantly shaped the course of Russian art, leaving behind a legacy as one of the most important chroniclers of the Russian people and their world. His art remains a testament to the power of realism to reflect, comment on, and ultimately, understand the human condition.