An Introduction to a Visionary Artist

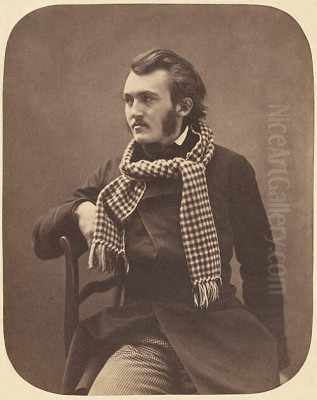

Paul Gustave Louis Christophe Doré, known universally as Gustave Doré, stands as one of the most prolific and influential artists of the 19th century. Born in Strasbourg, France, on January 6, 1832, Doré's life and career were marked by an extraordinary, almost preternatural talent that manifested across various artistic disciplines. Though he worked as a painter, sculptor, and caricaturist, his most enduring legacy lies in his work as a printmaker and, above all, an illustrator. His vivid, dramatic, and often fantastical interpretations of literary classics, the Bible, and contemporary life captured the public imagination like few artists before or since, cementing his place as a pivotal figure in the Romantic movement and beyond. His influence permeated not only the visual arts but also the nascent art form of cinema, leaving an indelible mark on how we visualize narrative and myth.

Doré's output was staggering, encompassing thousands of images that brought to life the works of authors ranging from Rabelais and Cervantes to Dante, Milton, and Poe. His unique style, characterized by dramatic chiaroscuro, meticulous detail, and a powerful sense of the sublime and the grotesque, made his illustrations instantly recognizable and immensely popular across Europe and America. Despite his widespread fame and commercial success as an illustrator, Doré harbored ambitions to be recognized primarily as a painter, a goal that proved more elusive, particularly within the critical circles of his native France. Nevertheless, his multifaceted career offers a fascinating study in artistic genius, ambition, and the complex relationship between popular appeal and critical acclaim in the vibrant art world of the 19th century.

Early Life and Prodigious Beginnings

Gustave Doré's artistic inclinations were apparent from an astonishingly early age. Born into a prosperous family, the son of an engineer, young Gustave displayed a talent for drawing that bordered on the prodigious. Reports suggest he was creating drawings by the age of four or five, already demonstrating a keen observational skill and a fertile imagination. Unlike many artists who undergo rigorous academic training, Doré was largely self-taught, his skills honed through relentless practice and an innate understanding of form and composition. His childhood was reportedly marked by a mischievous energy, with anecdotes telling of pranks and a restless spirit that sometimes clashed with formal schooling – one story even claims he was expelled for his antics, while another suggests he feigned illness simply to stay home and draw.

By the age of seven, he was already experimenting with lithography, a printmaking technique that would become crucial to his later career. His precocity was undeniable; at just ten years old, he is said to have created illustrations for Dante's Divine Comedy, a work he would famously illustrate professionally later in life. This early engagement with such profound literary material hints at the depth and ambition that would characterize his mature work. His family recognized his talent, and though his father initially hoped for a more conventional career path, Gustave's artistic destiny seemed unavoidable.

One charming, if perhaps apocryphal, anecdote tells of the young Doré collecting frogs and placing them in an elderly gentleman's bed, causing quite a fright. While possibly embellished, such stories contribute to the image of a lively, imaginative, and perhaps slightly rebellious youth, brimming with creative energy. By the age of fifteen, his talent was already too significant to ignore. He had moved to Paris with his mother following his father's death and secured his first professional contract, marking the official start of an unparalleled career in illustration.

The Rise Through Caricature and Illustration

Doré's professional journey began in Paris around 1847. At the remarkably young age of fifteen, he approached Charles Philipon, the influential publisher of satirical journals like Le Charivari and Journal pour rire (Journal for Laughing). Philipon, known for nurturing talents like Honoré Daumier, immediately recognized Doré's skill and offered him a three-year contract to produce weekly lithographic caricatures for Journal pour rire. This early work forced Doré to become a keen observer of Parisian life, honing his ability to capture character and social dynamics with wit and exaggeration. Some accounts mention his habit of sketching people in the streets, humorously transforming them into animal counterparts, revealing an early penchant for social commentary and the slightly grotesque.

This period provided invaluable experience and exposure. Doré quickly gained a reputation for his speed, versatility, and boundless imagination. His satirical drawings were popular, but his ambition soon extended beyond caricature towards the more prestigious field of book illustration. In 1853, he received a commission to illustrate the works of Lord Byron, followed swiftly by illustrations for François Rabelais's Gargantua and Pantagruel (1854). The Rabelais illustrations, full of earthy humor, fantastical creatures, and teeming crowds, showcased his ability to handle complex narratives and large-scale compositions, signaling a departure from simple caricature towards a more epic and detailed style.

His success grew rapidly. He illustrated Honoré de Balzac's Contes drolatiques (Droll Stories) in 1855, further cementing his reputation. By his early twenties, Doré was reportedly one of the highest-paid illustrators in France, a testament to both his extraordinary talent and his incredible work ethic. He was becoming the go-to artist for publishers seeking visually stunning editions of classic and contemporary literature. This early success laid the financial and artistic groundwork for the monumental projects that would define his mature career and secure his international fame.

Monumental Illustrations: Bible, Dante, and the Classics

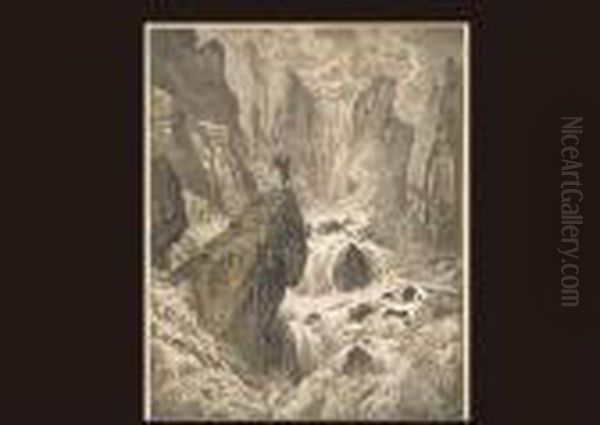

The late 1850s and 1860s marked the period of Doré's most ambitious and iconic illustrative projects. Driven by a desire to tackle grand themes, he embarked on a series of works that would become synonymous with his name. Perhaps the most pivotal was his self-funded edition of Dante Alighieri's Inferno (1861). Unable to find a publisher willing to risk such an expensive venture, Doré financed the publication himself. The gamble paid off spectacularly. The edition was an immediate sensation, lauded for its terrifyingly sublime depictions of Hell, its dramatic use of light and shadow, and its sheer imaginative power. The success prompted publishers to commission the remaining parts, Purgatorio and Paradiso (1868). Doré's Dante remains a benchmark in literary illustration, his visions arguably shaping the popular conception of Dante's afterlife more than any other artist, perhaps rivaled only in visionary intensity by the earlier work of William Blake.

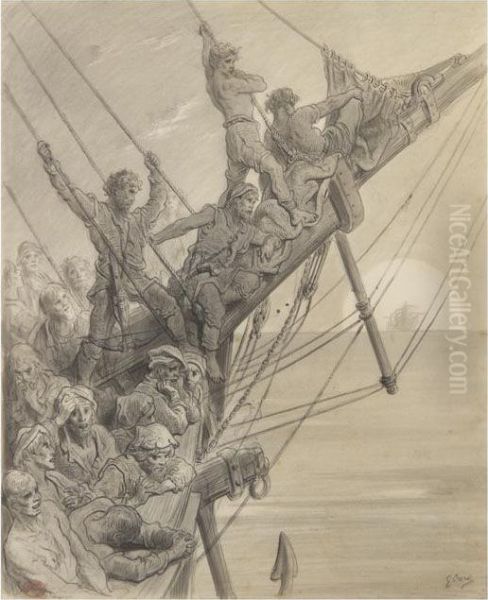

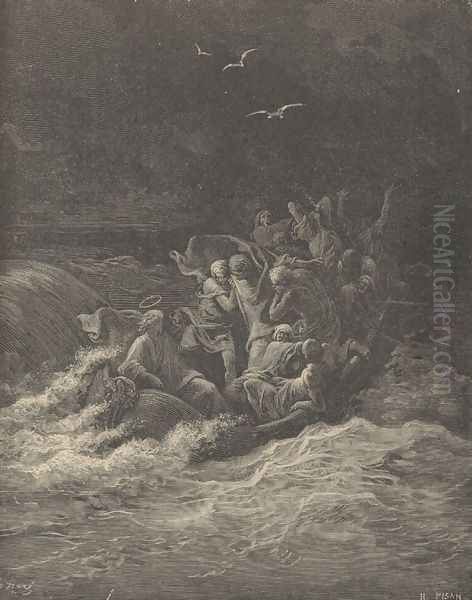

Buoyed by this success, Doré undertook an even larger project: illustrating the Bible (La Sainte Bible selon la Vulgate), published in two folio volumes in 1866. Containing 241 full-page illustrations, the Doré Bible was a monumental achievement and an enormous commercial success, translated and reprinted countless times across the globe. His depictions of epic scenes like the Creation, Noah's Ark, the Exodus, and the life of Christ were powerful and accessible, bringing the scriptures to life for a vast audience. While immensely popular, some critics felt the speed of production led to uneven quality or a certain theatricality that lacked spiritual depth, comparing his approach less favorably to the profound introspection found in the religious works of artists like Rembrandt van Rijn or the graphic clarity of Albrecht Dürer. Nonetheless, its impact was undeniable.

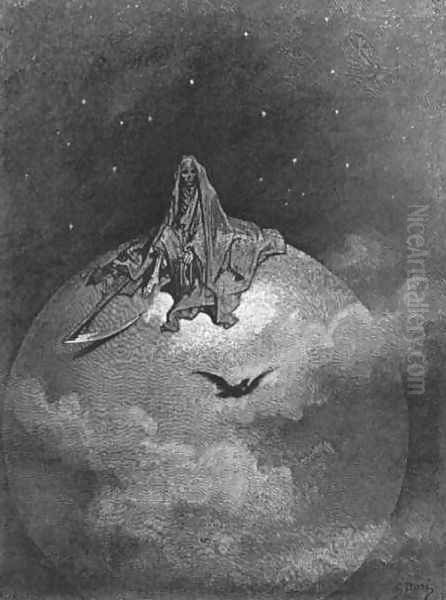

Doré's illustrative output during this period was relentless. He produced acclaimed illustrations for Cervantes' Don Quixote (1863), capturing both the comedic absurdity and the underlying pathos of the Knight of the Woeful Countenance, offering a richer visual interpretation than many predecessors like Charles-Antoine Coypel. Other major works included illustrations for Milton's Paradise Lost (1866), Tennyson's Idylls of the King (1867-68), La Fontaine's Fables (1867), Coleridge's Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1876), Edgar Allan Poe's The Raven (1884, one of his last works), and numerous fairy tales by Charles Perrault, including Little Red Riding Hood. Each project showcased his versatility and his uncanny ability to adapt his style to the specific mood and atmosphere of the text.

Artistic Style: Romanticism, Detail, and Drama

Gustave Doré's art is deeply rooted in the Romanticism that swept across Europe in the 19th century. His work embodies many key tenets of the movement: an emphasis on emotion, imagination, individualism, and the power of nature. He excelled at depicting the sublime – scenes that inspire awe mixed with terror, such as dramatic mountain landscapes, turbulent seas, or supernatural encounters. His historical and mythological subjects often focused on moments of high drama, intense struggle, or profound pathos, aligning with the Romantic fascination with the past and the exotic. There are also elements in his work, particularly the grotesque figures and dreamlike atmospheres, that foreshadow Symbolism.

Technically, Doré was a master draftsman. His compositions are often complex and dynamic, filled with figures and intricate details that draw the viewer in. His most defining characteristic is arguably his dramatic use of chiaroscuro – the strong contrast between light and dark. This technique, honed through his work in black and white illustration, creates a sense of volume, enhances the emotional impact, and imbues his scenes with a theatrical, almost cinematic quality. He often used light to spotlight key figures or moments, plunging surrounding areas into deep, mysterious shadow.

While Doré himself drew the designs, the final illustrations were typically produced as wood engravings. He would draw directly onto the wood block, which was then meticulously carved by a team of skilled engravers (artisans like Héliodore Pisan were among his most frequent collaborators). This process allowed for the reproduction of fine lines and complex textures, essential for capturing the detail Doré demanded. His mastery of this medium set a new standard for book illustration, demonstrating its potential for artistic expression on par with painting. His detailed, narrative-driven style stood in stark contrast to the emerging Impressionist movement, led by contemporaries like Claude Monet and Edgar Degas, who prioritized capturing fleeting moments and the effects of light with looser brushwork.

Beyond Illustration: Ambitions in Painting and Sculpture

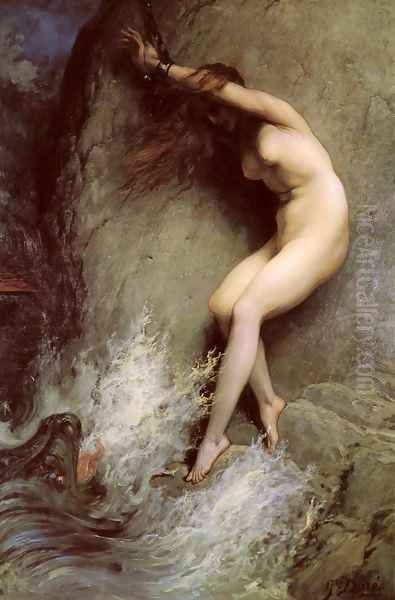

Despite achieving unparalleled fame and fortune through illustration, Gustave Doré yearned for recognition as a "serious" artist, particularly as a painter of historical and religious subjects, following in the grand tradition of French masters like Eugène Delacroix, a leading figure of Romantic painting. He dedicated significant time and resources to producing large-scale canvases, often depicting dramatic scenes from the Bible or history. Among his notable paintings are Christ Leaving the Praetorium (1867-1872), The Triumph of Christianity over Paganism (1868), Andromeda (1869), and The Neophyte (c. 1868). These works showcased his technical skill and dramatic flair but often met with a cooler reception from French critics compared to his illustrations. They were sometimes criticized for being overly theatrical or illustrative in nature, lacking the painterly qualities favored by the establishment.

Doré was also a gifted landscape painter. Inspired by his travels, he painted numerous scenes of the Scottish Highlands, the Swiss Alps, the Vosges mountains near his native Strasbourg, and the rugged landscapes of Spain. These works, often characterized by dramatic lighting and a sense of awe-inspiring nature, show an affinity with the landscape traditions of Romanticism, perhaps echoing the atmospheric power seen in the works of J.M.W. Turner. His landscapes, like his historical paintings, were often exhibited but struggled to achieve the same level of critical acclaim in Paris as his graphic work.

Furthermore, Doré ventured into sculpture later in his career. His sculptural works include the allegorical group La Parque et l'Amour (Fate and Love, 1877) and a monument to the writer Alexandre Dumas, père, unveiled in Paris in 1883, the year of Doré's death. He also created smaller bronzes and terracotta pieces. While his sculptural output was less extensive than his work in other media, it demonstrated his remarkable versatility and his persistent drive to explore different forms of artistic expression. His ambition across multiple fields highlights the breadth of his talent, even if history primarily remembers him for his groundbreaking illustrations.

The Doré Gallery and International Acclaim

While French critical opinion on Doré's paintings remained divided, he found immense popularity and validation abroad, particularly in Great Britain. In 1867 or 1868, capitalizing on his fame from the Bible and Dante illustrations, the Doré Gallery opened at 35 New Bond Street in London. This dedicated space primarily showcased his large-scale religious and historical paintings, which proved enormously popular with the British public. For nearly thirty years, the gallery was a major attraction, drawing crowds eager to see the dramatic canvases created by the famous illustrator.

The success of the Doré Gallery cemented his status as an international art star. His work resonated strongly with Victorian sensibilities, which appreciated narrative clarity, moral themes, and technical virtuosity. British and American audiences embraced his paintings with an enthusiasm that often eluded him in Paris. His illustrations continued to be published and widely disseminated in English-language editions, further solidifying his fame in the Anglophone world. He became a celebrated figure in London society, undertaking commissions and enjoying a level of popular adulation for his paintings that contrasted with the more reserved, sometimes dismissive, attitude of the Parisian art elite.

This international success highlights a recurring theme in art history: the divergence of popular taste and critical consensus. While Parisian critics might have favored the emerging avant-garde or adhered to stricter academic standards, Doré's powerful imagery and narrative skill captivated a broader public. His fame was comparable to that of other internationally successful artists of the era who appealed to Victorian tastes, such as James Tissot or Lawrence Alma-Tadema, though Doré's primary medium remained illustration. The Doré Gallery stands as a testament to his unique position as a commercially successful artist with a truly global reach.

Personal Life, Character, and Work Ethic

Gustave Doré's life was largely consumed by his art. His work ethic was legendary; estimates suggest he produced over 10,000 illustrations during his career, alongside numerous paintings, sculptures, and watercolors. This prodigious output required immense dedication and long hours spent in the studio. He was known for his incredible speed and facility, able to translate complex ideas onto paper or canvas with remarkable swiftness. This very speed, however, sometimes fueled criticism that his work could be superficial or overly reliant on formula.

Despite his fame and success, Doré's personal life appears relatively simple and centered around his work and family. He never married and lived with his mother, Alexandrine, for most of his adult life. He was deeply attached to her, and her death in 1881 affected him profoundly. Doré himself died relatively young, at the age of 51, on January 23, 1883, following a short illness, less than two years after his mother's passing. This close bond and his unmarried status have led some biographers to speculate about a certain loneliness or an emotional life largely sublimated into his art.

Anecdotes from his life paint a picture of a man with a lively sense of humor and a sociable nature, despite his intense focus on work. His early caricatures and reported habit of sketching people as animals suggest a witty and observant personality. He maintained friendships with prominent figures in the literary and artistic world, including the writer Théophile Gautier, who was an early admirer. Yet, the overwhelming impression is of an artist utterly devoted to his craft, driven by a relentless creative energy and a powerful ambition that spanned multiple artistic fields. His life was his art, and his legacy is the vast, imaginative world he created.

Enduring Influence and Legacy

Gustave Doré's impact on visual culture extends far beyond his own lifetime and the confines of 19th-century illustration. His dramatic compositions, mastery of light and shadow, and ability to create fantastical yet believable worlds left an indelible mark on subsequent generations of artists, illustrators, and filmmakers. His interpretations of classic texts like the Bible, Dante's Inferno, and Don Quixote became so iconic that they often overshadowed previous visualizations and continue to shape how these works are imagined today.

His influence on the burgeoning art of cinema is particularly noteworthy. Early filmmakers, grappling with how to tell epic stories visually, looked to Doré's illustrations for inspiration. His dynamic staging, dramatic lighting, and sense of scale provided a blueprint for cinematic spectacle. Directors like D.W. Griffith and Cecil B. DeMille, known for their historical epics and biblical dramas, likely drew upon Doré's visual vocabulary. The fantastical elements in his work also resonated with pioneers of fantasy and horror cinema, potentially influencing figures like Georges Méliès. Specific visual motifs from Doré's work have been cited as inspiration for scenes in films ranging from the original King Kong to later fantasy and horror movies. Even Disney animation is said to have looked at Doré, perhaps for the look of certain characters or environments.

Beyond film, Doré's influence can be seen in comic book art, fantasy illustration, and even video game design. Artists working in genres that require world-building, dramatic atmosphere, and the depiction of the extraordinary often echo Doré's techniques, consciously or unconsciously. Later illustrators specializing in fantasy and fairy tales, such as Arthur Rackham and Edmund Dulac, worked in a tradition that Doré had significantly shaped. Furthermore, his work was admired by fellow artists, including Vincent van Gogh, who famously painted his own version of Doré's illustration The Prisoners' Round (from London: A Pilgrimage). Doré remains arguably the most famous and commercially successful illustrator of the 19th century, his work a testament to the power of illustration to capture the imagination and define our collective visual understanding of literature and myth.

Conclusion: A Titan of Imagination

Gustave Doré was a force of nature in the 19th-century art world. Possessed of a rare and prodigious talent, he navigated the realms of illustration, painting, and sculpture with astonishing energy and ambition. While he craved recognition as a painter on par with the academic masters of his day, his most profound and lasting contribution lies in his unparalleled work as an illustrator. Through thousands of engravings, he brought literature to life with a vividness, drama, and imaginative depth that captivated millions and set a new standard for the art form.

His mastery of composition, his dramatic use of light and shadow, and his ability to conjure both the sublime and the grotesque made his style instantly recognizable and widely influential. From the depths of Dante's Hell to the epic landscapes of the Bible, from the satirical streets of Paris to the fantastical realms of fairy tales, Doré's vision shaped the way generations perceived these narratives. His work transcended the perceived boundaries between popular art and high culture, achieving international fame and leaving a legacy that continues to resonate in illustration, film, and the broader visual landscape. Gustave Doré remains a titan of imagination, an artist whose work continues to inspire awe and transport viewers to other worlds.