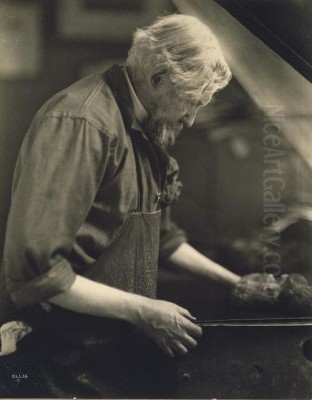

Joseph Pennell stands as a significant figure in American art history, a prolific and influential etcher, lithographer, illustrator, and author whose career bridged the 19th and 20th centuries. Born in Philadelphia in 1857 and passing away in New York City in 1926, Pennell's life and work reflect the dramatic changes of his era, from the historic cityscapes of Europe to the burgeoning industrial might of the United States. His technical mastery, particularly in etching and lithography, combined with a keen eye for architectural detail and atmospheric effect, earned him international recognition and left a lasting legacy on the world of printmaking.

Pennell's journey as an artist was multifaceted. He was not only a creator of images but also a chronicler of his times, a collaborator with his equally talented wife, Elizabeth Robins Pennell, a friend to many leading cultural figures, and a vocal advocate for the graphic arts. His vast output, numbering over nine hundred etchings alone, captured everything from serene European landscapes to the dynamic construction of the Panama Canal and the towering skyscrapers of New York City. Understanding Pennell requires exploring his formative years, his pivotal time in Europe, his engagement with modern themes, and his enduring influence.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Philadelphia

Joseph Pennell entered the world on July 4, 1857, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. His upbringing within a Quaker family was, by his own account, not entirely idyllic. He later described himself as a "lonely Puritan," suggesting a sense of detachment or isolation during his formative years. This feeling of being an outsider perhaps fueled his later drive and independent spirit as an artist. His academic performance in traditional schooling was reportedly unremarkable.

His initial path toward formal art training encountered obstacles. Pennell sought admission to the prestigious Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA), the oldest art museum and school in the United States, but was not initially accepted into the main program. Instead, he pursued studies at an industrial art school. However, he eventually did study at PAFA, where he came under the influence of the renowned American realist painter Thomas Eakins. Eakins's emphasis on anatomical accuracy, direct observation, and unvarnished depiction likely left an impression on the young Pennell, even though their primary mediums would differ.

Despite any early setbacks, Pennell quickly found his footing in the burgeoning field of illustration. Philadelphia, a major publishing center, offered opportunities. He began producing illustrations for various publications, honing his skills in drawing and composition. His early subjects often included historical landmarks and scenes accompanying travel articles, demonstrating an early interest in place and architecture that would become central to his life's work. This period laid the groundwork for his technical proficiency and his ability to capture the essence of a location through line and tone.

Launching a Career: Illustration and Early Prints

During the late 1870s and early 1880s, Pennell established himself as a capable illustrator. He worked for prominent American publishers, creating images that brought historical sites and travel narratives to life for a wide audience. This commercial work demanded clarity, accuracy, and the ability to translate complex scenes into reproducible formats, skills that served him well throughout his career. His focus on historical and architectural subjects during this time provided him with a deep visual vocabulary of forms and structures.

Simultaneously, Pennell began exploring the possibilities of original printmaking, particularly etching and lithography. He turned his attention to the industrial landscapes emerging around him in Pennsylvania and neighboring New York. Cities like Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, with their factories, bridges, and bustling waterfronts, offered compelling, if gritty, subject matter. These early prints reveal his developing technical command and his fascination with the textures and forms of the built environment, both old and new.

A pivotal development during this period was his meeting and subsequent marriage in 1884 to Elizabeth Robins (1855–1936), a talented writer and critic from a prominent Philadelphia family. Their union marked the beginning of a lifelong personal and professional partnership. Elizabeth became his most important collaborator, writing texts for many of the books he illustrated. Their shared intellectual and artistic interests created a powerful synergy that would define much of their subsequent careers.

The London Years and Whistler's Enduring Influence

The year 1884 marked a significant turning point in Pennell's life and career. He and Elizabeth moved to London, which would be their primary base for many years. London, then the vibrant heart of the British Empire and a major international art center, offered a stimulating environment. It was here that Pennell fully immersed himself in the European art scene and forged crucial relationships, none more important than his friendship with James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903).

Whistler, the expatriate American painter and etcher, was a leading figure in the Aesthetic Movement and a master of subtle tonalities and evocative compositions. Pennell deeply admired Whistler's work, particularly his etchings and lithographs, which captured atmospheric effects with remarkable delicacy. The two artists became close friends, and Whistler's artistic philosophy and technical approach profoundly influenced Pennell. Pennell absorbed Whistler's emphasis on suggestion over explicit detail, the careful arrangement of forms (often influenced by Japanese prints), and the pursuit of tonal harmony. Many of Pennell's subsequent works clearly show Whistler's impact in their handling of light, shadow, and atmospheric perspective.

Living in London, the Pennells became part of a dynamic cultural milieu. They associated with leading writers, artists, and intellectuals of the day, including figures like the playwright George Bernard Shaw, the author Robert Louis Stevenson, and the celebrated portrait painter John Singer Sargent. This network provided intellectual stimulation and further integrated them into the European cultural landscape. Their home became a gathering place for artists and writers, fostering a rich exchange of ideas.

During their time based in London, Joseph and Elizabeth collaborated extensively on travel books. Works like A Canterbury Pilgrimage (1885) and Our Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy (1887) combined Elizabeth's engaging prose with Joseph's evocative illustrations, capturing the landscapes, architecture, and ambiance of their travels. These popular books further cemented Pennell's reputation as a skilled illustrator with a unique ability to convey the spirit of place. His European subjects expanded significantly during this period, encompassing cathedrals, castles, city streets, and river views across the continent.

Mastering the Mediums: Etching and Lithography

While illustration provided a steady income and wide exposure, Pennell's artistic heart lay in original printmaking. He became a leading figure in the Etching Revival, a movement that began in the mid-19th century and sought to elevate etching from a reproductive craft back to a respected medium for original artistic expression. Artists like Whistler and Sir Francis Seymour Haden in Britain, and Félix Bracquemond in France, were key proponents, and Pennell joined their ranks as a dedicated and innovative practitioner.

Pennell's technical skill in etching was exceptional. He mastered the various techniques involved – from preparing the plate and drawing through the wax ground with a needle, to the controlled biting of the lines with acid and the nuanced wiping of ink for printing. His lines could be both precise and suggestive, capable of rendering intricate architectural detail or capturing fleeting effects of light and weather. He often worked directly on the plate from nature, preserving a sense of immediacy and spontaneity in his prints.

His output was prodigious, eventually exceeding 900 etchings, alongside numerous lithographs and drawings. His subjects remained diverse, covering the historical landmarks of Europe, the picturesque landscapes encountered on his travels, and increasingly, the dynamic architecture of modern cities. He possessed a remarkable ability to translate the three-dimensional world into the linear language of etching, using cross-hatching, varied line weight, and selective plate tone to create depth, texture, and atmosphere.

Pennell was also an accomplished lithographer. Lithography, drawing directly on stone or a prepared plate for printing, allowed for a different range of effects, often softer and more painterly than etching. Pennell embraced lithography particularly for capturing tonal subtleties, atmospheric conditions, and the dramatic chiaroscuro of industrial scenes and night views. His technical versatility across these demanding printmaking mediums solidified his reputation as a master craftsman.

Documenting the Modern World: Architecture and Industry

While deeply appreciative of historical architecture and European scenery, Pennell was equally fascinated by the dynamism and scale of the modern world, particularly as manifested in American industry and urban development. He turned his sharp eye and skilled hand to capturing the rapidly changing skylines and monumental engineering projects of the early 20th century. This engagement with contemporary subjects distinguished him from many artists focused solely on traditional themes.

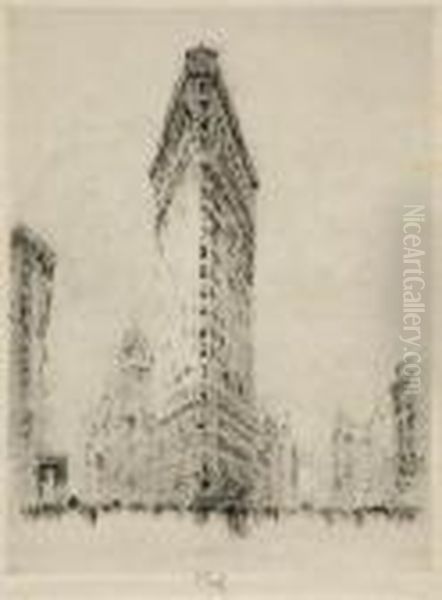

His depictions of New York City are among his most celebrated works. He chronicled the rise of the skyscraper, capturing iconic structures like the Flatiron Building (1904) in etchings that emphasized its soaring verticality and unique presence. He rendered the intricate structure and majestic sweep of the Brooklyn Bridge and captured the bustling energy of the city's harbor in works like The Harbour And The Statue Of Liberty (1909) and Winter Sunset, New York Harbor. Prints like The Stone Hole in West Street documented the constant construction and transformation of the urban landscape. These images convey both the grandeur and the grit of the modern metropolis. His approach often echoed the compositional strategies of Whistler but applied them to the new, often overwhelming, scale of American architecture.

Pennell's interest in industry extended beyond cityscapes. Commissioned to document the construction of the Panama Canal, he traveled to Panama in 1912. The resulting series of lithographs powerfully captures the immense scale and human effort involved in this colossal engineering feat. He depicted the massive locks, the deep cuts through the earth, and the machinery reshaping the landscape, finding a dramatic, almost sublime beauty in the industrial process. These works stand as a unique artistic record of one of the century's great technological achievements. His ability to find aesthetic power in industrial subjects connected him thematically, if not always stylistically, to American artists like the Ashcan School painters (such as John Sloan or George Bellows) who also depicted the realities of modern urban life.

Wartime Contributions and Later Work

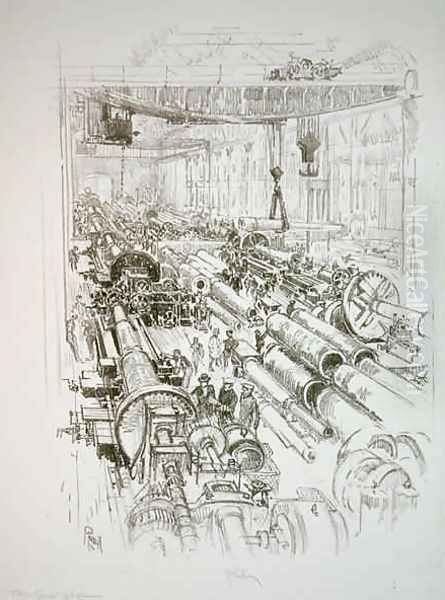

The outbreak of World War I prompted Pennell's return to the United States, although he also spent time documenting war efforts in Britain and France. Deeply patriotic, he dedicated his artistic talents to supporting the Allied cause. He produced a powerful series of lithographs depicting war industries – munitions factories, shipyards, aircraft plants – both in America and Europe. Works like The Gun Shop and images of factories churning out war materials highlighted the industrial might behind the war effort.

These wartime prints, often characterized by dramatic lighting and strong compositions, served as both documentation and propaganda. Titles like War Cathedrals imbued industrial sites with a sense of awe and national purpose. He created posters, including the striking Lest Liberty Perish, urging support for Liberty Loans. This period demonstrated Pennell's ability to adapt his art to pressing contemporary events and use it for persuasive communication, showcasing the power of the print medium in shaping public opinion.

In the post-war years, Pennell continued to work, teach, and write. He remained fascinated by the ever-evolving cityscape of New York and other American industrial centers. His style, while still rooted in the principles learned from Whistler and the Etching Revival, continued to engage with the forms and energy of the 20th century. He maintained his commitment to the craft of printmaking, advocating for high standards in technique and presentation.

Author, Educator, and Advocate

Beyond his prolific output as an artist, Joseph Pennell was also a significant author and educator. His collaboration with Elizabeth Robins Pennell extended to biographical works, most notably their authorized The Life of James McNeill Whistler (1908). This extensive, two-volume work, based on their close friendship with the artist and access to his papers, remains a foundational text for Whistler scholarship, offering invaluable insights into his life, personality, and artistic methods. The Pennells fiercely defended Whistler's reputation and artistic legacy.

Joseph Pennell also authored several influential books on the techniques of illustration and printmaking himself. Titles like Pen Drawing and Pen Draughtsmen (1889), The Illustration of Books (1896), and Etchers and Etching (1919) served as practical guides and aesthetic manifestos. In these writings, he shared his technical knowledge, discussed the work of historical and contemporary masters (referencing artists from Albrecht Dürer to contemporaries like Anders Zorn), and championed high standards in graphic arts. He was often opinionated and direct in his assessments, reflecting his strong convictions about artistic quality.

His commitment to the graphic arts extended to teaching. Pennell taught illustration and printmaking techniques at important institutions, including the Slade School of Fine Art in London and the Art Students League of New York. He shared his expertise and passion with younger generations of artists, contributing to the continuation of printmaking traditions. He was also active in various art societies, promoting exhibitions and advocating for the recognition of etchers and illustrators. His role as an educator and advocate complemented his artistic practice, making him a central figure in the printmaking world of his time.

Personality and Reputation

Joseph Pennell was known for his strong personality and outspoken views. His Quaker background perhaps instilled a certain directness, but he was far from reserved. Friends and critics alike noted his tendency towards passionate, sometimes contentious, pronouncements on art and artists. One acquaintance famously described him as one of the "noisiest of Puritans," capturing this blend of conviction and volubility.

His fierce loyalty to friends like Whistler was matched by his sharp criticism of art he deemed mediocre or pretentious. He engaged in public debates about artistic standards, the role of illustration, and the state of printmaking. This outspokenness sometimes led to friction with fellow artists and critics, but it also underscored his deep commitment to the principles he believed in. He was unafraid to challenge conventional wisdom or defend unpopular positions if he felt artistic integrity was at stake.

His personality undoubtedly shaped his career. His confidence and assertiveness helped him navigate the competitive art worlds of Philadelphia, London, and New York. His collaborations, particularly with his wife Elizabeth, were central to his success, suggesting an ability to work closely with those he trusted and respected. While sometimes controversial, his strong voice ensured that his views on art and technique were widely heard and debated, contributing to the critical discourse of his time.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Joseph Pennell's death from heart failure in Brooklyn, New York, on April 23, 1926, marked the end of a remarkably productive and influential career. He left behind a vast body of work – etchings, lithographs, drawings, and illustrations – that provides a rich visual record of his era. His contributions to the Etching Revival were substantial; he not only mastered the medium but also pushed its boundaries and advocated passionately for its status as a fine art. His technical prowess influenced countless printmakers who followed.

His dedication to depicting modern subjects, particularly industrial sites and urban architecture, was pioneering. While artists like Childe Hassam also created etchings of city life, Pennell's focus on the monumental scale of industry and construction was particularly distinctive. He found aesthetic power in subjects previously considered unpicturesque, paving the way for later artists to explore the visual language of the modern industrial landscape. His work documenting the Panama Canal and the skyscrapers of New York remains iconic.

Through his teaching and writing, Pennell disseminated technical knowledge and aesthetic principles that shaped the understanding and practice of printmaking and illustration for generations. His books remained standard references for many years. His advocacy helped elevate the status of the graphic arts. While specific stylistic influence can be hard to trace definitively, his commitment to craft and his engagement with contemporary life inspired many artists, including members of later printmaking societies like the California Society of Etchers. Artists like John Taylor Arms, known for his meticulous architectural etchings, certainly worked in a tradition Pennell helped solidify.

Pennell and his wife bequeathed a large collection of prints and papers, including an important collection of Whistleriana, to the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. Tragically, a portion of his own work stored during World War I was damaged or lost due to negligence, a sad footnote to a career dedicated to the art of the print. Nevertheless, the surviving works in public and private collections worldwide attest to his skill, vision, and importance in American and international art history.

Conclusion

Joseph Pennell was more than just a technically brilliant etcher and illustrator; he was a vital participant in the artistic currents of his time. From the studios of Philadelphia to the salons of London and the bustling streets of New York, he absorbed, interpreted, and recorded the world around him. His deep connection with James McNeill Whistler shaped his aesthetic, but he forged his own path, applying those principles to the unique landscapes and burgeoning industries of America. His collaboration with Elizabeth Robins Pennell created a unique body of illustrated literature. As an artist, author, teacher, and advocate, Joseph Pennell left an indelible mark on the graphic arts, capturing the transition from the 19th to the 20th century with skill, passion, and an unwavering commitment to his craft. His work continues to resonate, offering compelling glimpses into the past and celebrating the enduring power of line and tone.