Hermann Struck stands as a significant figure in early 20th-century art, renowned primarily as a master etcher and lithographer. Born in Berlin, Germany, yet deeply connected to his Jewish heritage and the burgeoning Zionist movement, Struck navigated the complex cultural and political currents of his time. His life and work bridge the gap between European artistic traditions and the nascent cultural landscape of Palestine, leaving a legacy as both a creator and an influential teacher. His original Hebrew name, Chaim Aaron ben David, signaled the deep roots from which his artistic and personal identity would grow.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations in Berlin

Hermann Struck was born into an Orthodox Jewish family in Berlin on March 24, 1876. This background, steeped in tradition and with familial ties to rabbinical lineage, profoundly shaped his worldview and often informed the subjects of his art. He pursued formal artistic training at the prestigious Berlin Academy of Fine Arts (Berliner Akademie der Künste), where he honed his skills, particularly in the demanding medium of etching.

His dedication and talent quickly became apparent. Struck immersed himself in the techniques of printmaking, exploring the expressive potential of line, shadow, and texture achievable through etching and lithography. This period of intense study laid the groundwork for his future renown not only as an artist but also as a leading authority on printmaking techniques.

The Art of Etching: A Seminal Work

In 1908, Struck published Die Kunst des Radierens (The Art of Etching). This comprehensive volume was far more than a simple manual; it was a detailed exploration of the history, techniques, and aesthetics of etching. The book quickly became a standard text for aspiring and established artists alike, translated into multiple languages and cementing Struck's reputation as a foremost expert in the field.

Die Kunst des Radierens detailed various processes, from preparing the plate and using different grounds to the nuances of acid biting and printing. Its clarity, depth, and inclusion of examples made it an indispensable resource. The publication demonstrated Struck's commitment not only to his own artistic practice but also to the education and advancement of the graphic arts, establishing him as a pivotal figure in the printmaking world of the early 20th century.

Artistic Style and Influences

While primarily celebrated for his graphic work, Struck's artistic sensibilities were shaped by the diverse movements flourishing during his formative years. Influences from Impressionism and Post-Impressionism can be discerned in his handling of light and atmosphere, particularly in his landscape works. Though not strictly an Expressionist, the emotional intensity and focus on subjective experience found in German Expressionism, championed by artists like those in Die Brücke (e.g., Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff) or Der Blaue Reiter (e.g., Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc), likely resonated with his desire to convey deeper meaning beyond mere representation.

However, Struck's core style remained largely rooted in a sensitive realism, especially evident in his portraiture. He possessed a remarkable ability to capture not just the likeness but also the character and inner life of his subjects through meticulous linework and subtle tonal gradations. His landscapes, whether of European cities, German countryside, or later, the vistas of Palestine, convey a strong sense of place and atmosphere. He worked across various media, including etching, lithography, and occasionally painting, demonstrating versatility but always returning to the graphic arts as his primary mode of expression.

A Prolific Portraitist

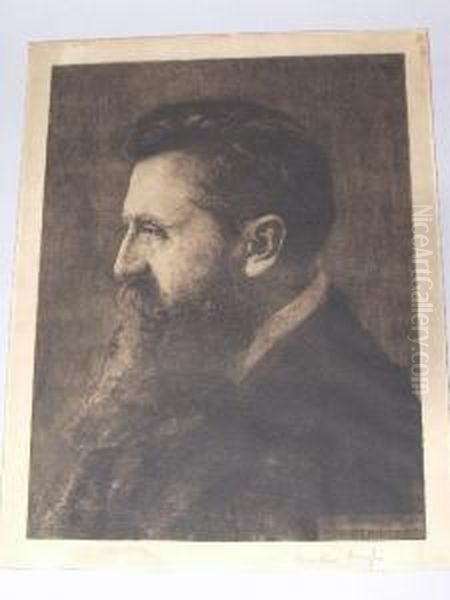

Hermann Struck was a highly sought-after portraitist, capturing the likenesses of many prominent figures of his time. His sitters included leading intellectuals, writers, scientists, and fellow artists. Among his most famous portraits are those of the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, the father of psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud, the physicist Albert Einstein, and playwrights like Henrik Ibsen. These portraits are valued not only as historical documents but also as insightful artistic interpretations.

His ability to connect with his sitters and translate their essence onto the plate was remarkable. The portrait of Theodor Herzl, the visionary founder of modern political Zionism, created in 1903, is particularly significant, reflecting Struck's own deep commitment to the Zionist cause. He also depicted literary figures such as Hermann Hesse and Arnold Zweig, with whom he would later collaborate. These works showcase his skill in capturing intellectual depth and personality through the precise art of etching.

The Master as Teacher

Beyond his own prolific output, Struck was a dedicated and influential educator. He generously shared his extensive knowledge of printmaking techniques, mentoring a generation of artists in Berlin and later in Palestine. His reputation, bolstered by Die Kunst des Radierens, drew many students eager to learn the intricacies of etching and lithography from the master himself.

His pupils included artists who would go on to achieve significant recognition in their own right. Among the most notable were Marc Chagall, whom Struck taught etching techniques during Chagall's time in Berlin around 1922-23. Others who benefited from his instruction included major figures of German art like Lovis Corinth and Max Liebermann (though perhaps more colleagues learning specific techniques), as well as artists central to the development of Israeli art, such as Jacob Steinhardt, Lesser Ury, and Joseph Budko. His pedagogical legacy extended through these artists, disseminating his technical expertise and artistic values. Other contemporaries whose paths likely crossed or whose work existed in the same milieu include Max Slevogt and Käthe Kollwitz, both significant German printmakers.

Zionism and the Call of Palestine

From early on, Hermann Struck was deeply involved in the Zionist movement, which aimed to establish a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Unlike purely political activists, Struck saw Zionism through a cultural and spiritual lens, believing in the importance of a revived Jewish life and art in its ancestral land. He was an active member of the Mizrachi movement, a religious Zionist organization.

His commitment was not merely ideological; it was deeply personal. In 1903, long before his eventual emigration, Struck made his first journey to Palestine (Eretz Israel). This visit profoundly impacted him, providing firsthand experience of the landscapes, people, and atmosphere of the land that held such significance for Jewish history and identity. This trip yielded numerous sketches and prints, marking the beginning of his artistic engagement with the region that would become his home.

World War I and 'The Face of East European Jewry'

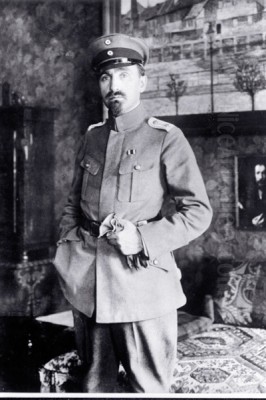

The outbreak of World War I saw Struck serve in the German army. He was assigned as an interpreter and liaison officer dealing with Jewish affairs on the Eastern Front, primarily in Lithuania and Poland (Congress Poland/Russian partition). This role brought him into close contact with the vibrant, traditional Jewish communities of the shtetls – worlds culturally distinct from the assimilated Jewish society of Berlin he knew.

His experiences during the war were artistically fruitful, if born from conflict. He meticulously documented the life, faces, and environments of these Eastern European Jewish communities through numerous sketches and drawings. This work provided the foundation for one of his most significant collaborative projects. Struck was awarded the Iron Cross for his service, a testament to his duties performed, yet the encounters on the Eastern Front arguably had a more lasting impact on his artistic direction.

Following the war, Struck collaborated with the writer Arnold Zweig on the book Das ostjüdische Antlitz (The Face of East European Jewry), published in 1920. Struck provided the powerful etchings and lithographs, while Zweig wrote the accompanying text. The book aimed to present an authentic portrait of Eastern European Jewry to a Western audience, countering stereotypes and highlighting the perceived spiritual depth and cultural richness that some, like Struck and Zweig, felt was diminishing among Western Jews. It remains a poignant document of a world soon to be devastated.

Emigration and Life in Haifa

Driven by his Zionist convictions and likely sensing the changing, increasingly hostile atmosphere in Germany even before the Nazis came to power, Struck decided to make Aliyah (immigrate to Palestine). Around 1922 or 1923, he and his wife Mally settled in Haifa, choosing the Hadar HaCarmel neighborhood, which offered stunning views of the bay and the growing port city.

In Palestine, Struck quickly became a central figure in the developing cultural life of the Yishuv (the pre-state Jewish community). He continued to create art, now focusing on the landscapes and people of his new home. He was instrumental in the founding and development of key artistic institutions. He played a role in the early stages of the Tel Aviv Museum of Art and was closely involved with the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem, serving on its board and teaching there, further influencing a new generation of artists working in Palestine.

Artistic Themes in the Land of Israel

Struck's move to Palestine marked a new chapter in his artistic subject matter. While he continued to create portraits, his focus increasingly turned to the unique landscapes of the region. He captured the hills of the Galilee, the ancient streets of Jerusalem and Safed, the shores of the Sea of Galilee (Lake Kinneret), and the burgeoning city of Haifa itself.

His style adapted subtly to the intense light and distinct atmosphere of the Middle East. His etchings and lithographs from this period often convey a sense of timelessness, connecting the contemporary reality of the Yishuv with the deep historical and biblical resonance of the land. He depicted Jewish pioneers, Arab villagers, ancient olive groves, and panoramic vistas, contributing significantly to the visual identity of the nascent Israeli culture. His work provided a European-trained perspective infused with a deep emotional connection to the subject matter.

Legacy and Collections

Hermann Struck passed away in Haifa on January 11, 1944, before the establishment of the State of Israel but having contributed significantly to its cultural foundations. His influence extended far beyond his own impressive body of work. As a teacher, he shaped the skills and perspectives of numerous artists in both Europe and Palestine. As a Zionist cultural figure, he helped build the institutions that would nurture Israeli art for decades to come.

His former home in Haifa was eventually transformed into the Hermann Struck Museum, dedicated to preserving and exhibiting his work and life. It stands as a testament to his artistic achievements and his dedication to his adopted city. Today, Struck's works are held in major collections worldwide, reflecting his international stature.

Significant holdings can be found at the Leo Baeck Institute in New York, which specializes in the history and culture of German-speaking Jewry. Israeli institutions like the Tel Aviv Museum of Art and the Haifa Museums (which administers the Struck Museum) hold extensive collections. The Jewish Museum Frankfurt has also featured his work. His prints continue to be studied and admired for their technical mastery, historical significance, and the sensitive humanism that pervades his depictions of people and places.

Conclusion: Bridging Worlds

Hermann Struck's life and art represent a fascinating confluence of identities and influences. He was a German artist steeped in European traditions, yet also a devout Jew and committed Zionist who embraced a new life in Palestine. His mastery of etching placed him among the leading printmakers of his generation, while his book Die Kunst des Radierens codified and disseminated that knowledge widely.

Through his portraits, he chronicled the intellectual and cultural elite of his time. Through his landscapes and genre scenes, particularly those from Eastern Europe and Palestine, he documented worlds undergoing profound change, capturing moments of cultural encounter and historical transition. As an educator and institution builder, his impact resonated through the generations of artists he taught and the cultural organizations he helped establish. Hermann Struck remains a vital figure for understanding the intersection of European art, Jewish identity, and the cultural rebirth associated with the Zionist movement in the early 20th century. His legacy endures in his art and in the cultural landscape he helped to shape.