Jost Amman (1539-1591) stands as one of the most industrious and influential artists of the late German Renaissance, a period teeming with artistic innovation and cultural transformation. Born in Zurich, Switzerland, and spending the majority of his prolific career in the bustling artistic and commercial hub of Nuremberg, Germany, Amman's legacy is primarily cemented by his vast output of woodcuts and etchings, particularly those designed for book illustration. His work provides an invaluable window into the society, beliefs, and daily life of 16th-century Europe, capturing everything from biblical narratives and classical mythology to contemporary trades and courtly life with remarkable skill and an elegant, distinctive style.

Early Life and Formative Influences

Jost Amman was born on June 13, 1539, in Zurich, Switzerland. His upbringing was in an intellectually stimulating environment; his father, Johann Jakob Ammann, was a respected professor of classical languages and logic. This academic background likely provided young Jost with a broad education and a deep appreciation for literature and history, themes that would later permeate his artistic oeuvre. Zurich, at this time, was a significant center of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that had profound implications for the visual arts, shifting focus and patronage, and often encouraging more didactic and accessible forms of imagery, such as prints.

While details of his earliest artistic training are scarce, it is known that Amman showed considerable talent from a young age. He is believed to have initially worked briefly in Basel around 1559 or early 1560. Basel was another vibrant center for printing and humanism, famously associated with figures like Erasmus and the Holbein family of artists. It is plausible that Amman encountered the work of artists like Hans Holbein the Younger (c. 1497-1543), whose precision and insightful portraiture had set a high standard, or the dynamic prints of Urs Graf (c. 1485-1528), a Swiss artist known for his often gritty and unconventional imagery. The artistic atmosphere in these Swiss cities, with their strong traditions in printmaking and book production, would have been formative for the young artist.

Relocation to Nuremberg and Rise to Prominence

Around 1560 or 1561, Jost Amman made a pivotal decision to relocate to Nuremberg. This imperial free city was one of Germany's most important artistic and commercial centers, a powerhouse of printing, publishing, and craftsmanship. It had been the home of Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), whose genius had elevated printmaking to a major art form and whose influence still resonated powerfully. Nuremberg also boasted a thriving community of skilled artisans, including goldsmiths like the famed Wenzel Jamnitzer (1507/8-1585), and a robust publishing industry.

In Nuremberg, Amman's talents quickly found an outlet. He began working as an independent master, and his skill, speed, and versatility made him highly sought after, especially by publishers. One of his most significant early associations in Nuremberg was likely with the workshop of Virgil Solis (1514-1562), a prolific printmaker and publisher. Solis died shortly after Amman's arrival, but it's possible Amman worked for him or was significantly influenced by his workshop's output, which specialized in a wide range of small-format illustrations. Amman's ability to produce a vast number of detailed and lively designs efficiently was a key factor in his success. He officially became a citizen of Nuremberg in 1577, a testament to his established position within the city's artistic community.

The Art of Book Illustration: Amman's Primary Domain

Jost Amman's most enduring contribution lies in the field of book illustration. He was arguably the most prolific book illustrator of his generation in Germany. He collaborated extensively with Sigmund Feyerabend (1528-1590), one of the leading publishers and booksellers in Frankfurt am Main, who also had operations in Nuremberg. Feyerabend recognized Amman's talent for creating appealing and informative images that could enhance the commercial success of his publications.

Amman's illustrations graced a wide array of books, including Bibles, classical texts, historical chronicles, costume books, heraldic manuals, treatises on warfare, and books on various crafts and professions. His woodcuts were prized for their clarity, lively figures, and attention to detail. He possessed an ability to distill complex narratives or concepts into compelling visual compositions that were both informative and aesthetically pleasing. The sheer volume of his output is staggering; it is estimated that he produced over 1,500 woodcuts, in addition to etchings and drawings. An anecdote, possibly apocryphal but indicative of his reputation, claimed that he produced enough drawings in four years to fill a hay wagon.

His style was characterized by elegant, slender figures, often depicted in dynamic poses. He had a keen eye for costume and accoutrements, rendering them with a precision that makes his works valuable historical documents. His lines are typically fine and controlled, creating a sense of refinement even in bustling scenes. While perhaps not possessing the profound psychological depth of Dürer or the dramatic intensity of Matthias Grünewald (c. 1470-1528), Amman excelled in narrative clarity and decorative appeal.

Key Collaborations and Major Works

Amman's career was marked by several important collaborations that resulted in some of his most famous works. His partnership with Sigmund Feyerabend was paramount, leading to numerous illustrated volumes that reached a wide audience.

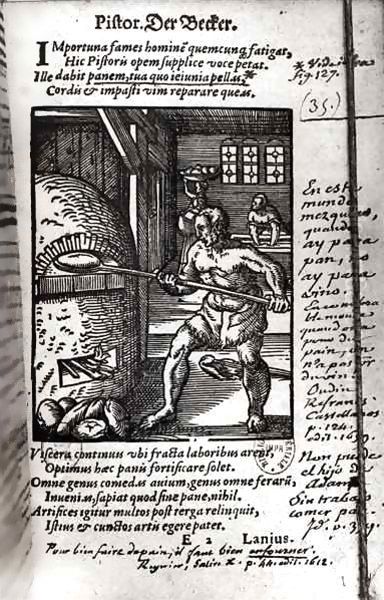

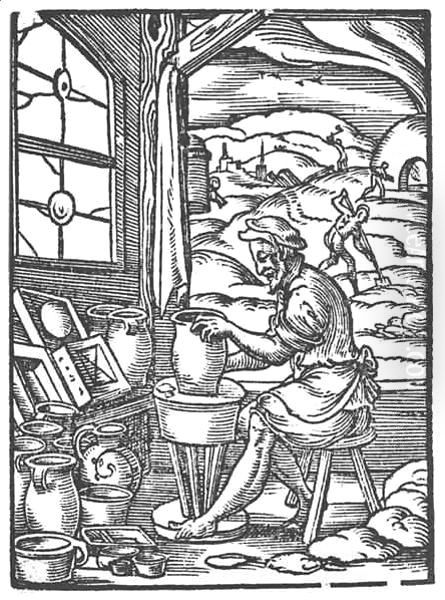

One of his most celebrated achievements is the Panoplia Omnium Liberalium Mechanicarum et Sedenatariarum Artium Genera Continens (commonly known as the Ständebuch or Book of Trades), published by Feyerabend in 1568. This landmark work features 114 woodcuts by Amman, each depicting a different trade or profession, from the Pope and Emperor down to humble artisans like the spoon maker or the peasant. Each illustration is accompanied by a short descriptive verse by the Nuremberg poet Hans Sachs (1494-1576). The Hatter is a prime example from this series, showcasing three craftsmen diligently at work, surrounded by the tools and products of their trade. The Ständebuch is a remarkable visual encyclopedia of 16th-century society and labor, and Amman's lively and detailed depictions bring these occupations to life.

Amman also produced extensive series of biblical illustrations. His Neue Biblische Figuren des Alten und Neuen Testaments (New Biblical Figures of the Old and New Testament), published by Feyerabend, provided vivid visual interpretations of key scriptural stories. Works like The Apocalyptic Woman and the Seven-Headed Dragon demonstrate his ability to tackle complex allegorical subjects with dramatic flair. These illustrated Bibles were crucial in an era when literacy was not universal, allowing broader access to religious narratives.

He provided illustrations for Wenzel Jamnitzer's Perspectiva Corporum Regularium (Perspective of Regular Solids), published in 1568. This collaboration with the renowned goldsmith and master of perspective underscores Amman's versatility and his engagement with the scientific and theoretical currents of the Renaissance. His ability to render complex geometric forms accurately was essential for such a project.

Other notable publications featuring Amman's work include costume books like Gynaeceum, sive Theatrum Mulierum (Theatre of Women, 1586), showcasing female attire from various regions and social classes, and Kunnst und Lehrbüchlein für die anfahenden Jungen Daraus reissen und malen zu lernen (Art and Instruction Book for Young Beginners to Learn Drawing and Painting, 1578), a drawing manual that demonstrates his pedagogical interests. He also illustrated historical works, such as chronicles of Roman emperors or depictions of contemporary military campaigns, like The Battle of the Romans and the Bavarians. His skill in heraldry is evident in works like the Wappen- und Stammbuch (Book of Arms and Lineages, 1589).

Artistic Style, Techniques, and Versatility

Jost Amman was proficient in several media, though he is best known for his woodcuts. The woodcut technique, which involves carving a design into a block of wood, leaving the lines to be printed in relief, was the dominant medium for book illustration in the 16th century due to its compatibility with letterpress printing. Amman's woodcuts are characterized by their fine, often intricate linework, which required considerable skill from both Amman as the designer and the block cutters (Formschneider) who translated his drawings onto the wood. His style evolved towards a greater delicacy and elegance, with elongated figures and a sophisticated sense of composition.

He also produced a significant number of etchings. Etching, a process where lines are incised into a metal plate using acid, allows for a freer, more calligraphic line than woodcut or engraving. Amman's etchings often display a greater spontaneity and fluidity. Beyond prints, he was also a painter, though fewer of his paintings survive or are securely attributed. He is also known to have designed stained glass.

His figures are typically graceful and animated, conveying a sense of movement and life. He paid meticulous attention to details of costume, armor, and setting, which lends an air of authenticity to his scenes, whether they depict biblical events, historical battles, or contemporary life. This precision makes his works invaluable for historians studying the material culture of the period. His compositions are generally well-balanced and clear, effectively conveying the intended narrative or information.

While working within the broader traditions of the German Renaissance, Amman's style is distinct. It is less monumental and perhaps less overtly emotional than that of Dürer or Grünewald, but it possesses a refined elegance and a narrative directness that was perfectly suited to the demands of book illustration. His work can be seen as a bridge between the High Renaissance and the emerging Mannerist tendencies, with its elongated proportions and sophisticated poses.

Amman in the Context of His Contemporaries

Jost Amman operated within a rich artistic landscape. While Dürer had passed away before Amman's career began, his legacy loomed large in Nuremberg. Other notable German artists of the 16th century included Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472-1553) and his son Lucas Cranach the Younger (1515-1586), who were pivotal figures in the art of the Reformation in Saxony, known for their portraits and allegorical scenes. Albrecht Altdorfer (c. 1480-1538) of the Danube School had been a pioneer in landscape painting and expressive printmaking.

In Switzerland, contemporary to Amman's early years or slightly preceding him, artists like Niklaus Manuel Deutsch (c. 1484-1530) were known for their powerful, often politically charged imagery related to the Reformation and mercenary life. Tobias Stimmer (1539-1584), an exact contemporary of Amman, also born in Switzerland (Schaffhausen) and active in Strasbourg and Basel, was another highly prolific illustrator and painter, known for his facade paintings and book illustrations. Their careers share parallels in terms of productivity and focus on illustrative work. Hans Bock the Elder (c. 1550-1624), active in Basel, continued the Swiss tradition of painting and design. Earlier Swiss artists like Hans Leu the Younger (c. 1490-1531) and Hans Fries (c. 1465-c. 1523) had contributed to the late Gothic and early Renaissance art of the region.

Amman's relationship with Virgil Solis's workshop is significant. Solis himself was a highly productive artist, and his workshop produced a vast number of prints that were widely disseminated. Amman built upon this model of prolific, commercially successful print production. His work, like that of Solis, catered to a growing market for illustrated books among an increasingly literate populace and a wealthy bourgeoisie eager for knowledge and visual culture.

Influence and Lasting Legacy

Jost Amman's influence during his lifetime and in the succeeding decades was considerable, primarily due to the wide circulation of the books he illustrated. His designs were frequently copied and adapted by other artists and craftsmen across Europe. His depictions of costumes, trades, and historical events served as a visual reference for many.

His Ständebuch remained influential for centuries, inspiring similar works and providing a rich source for understanding historical professions. His drawing manuals, like the Kunst- und Lehrbüchlein, contributed to art education. The clarity and elegance of his style set a standard for book illustration that persisted for many years. Some art historians have even suggested that his dynamic compositions and figure types may have had an impact on later Baroque masters such as Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) and Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641), who would have encountered his prints.

Though perhaps not always ranked among the very top tier of "genius" artists like Dürer or Holbein, Amman's importance lies in his incredible productivity, his skill in making complex subjects accessible and visually engaging, and his role in the burgeoning print culture of the 16th century. He was a master craftsman and a keen observer of the world around him, and his work democratized access to imagery and information on an unprecedented scale.

Amman's Works in Collections and the Art Market

Today, Jost Amman's prints are held in the collections of major museums and libraries worldwide. Institutions such as the Art Institute of Chicago, the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, the Department of Graphic Arts at the Louvre Museum in Paris, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., and the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam all house significant examples of his work.

His prints, particularly individual sheets or disbound illustrations from his books, appear regularly on the art market. Auction houses like Ketterer Kunst and Auktionshaus Schramm, among others, have handled sales of his works. The value of his prints can vary widely depending on rarity, condition, quality of the impression, and subject matter. Complete, well-preserved copies of the books he illustrated, especially seminal works like the Ständebuch, are highly prized by collectors and institutions.

Jost Amman died in Nuremberg on March 17, 1591, at the age of 52. He left behind an immense body of work that continues to fascinate scholars, collectors, and art enthusiasts. His prints are not merely illustrations; they are vibrant historical documents that offer a rich tapestry of 16th-century life, rendered with an elegance and technical skill that affirm his status as a significant master of the German Renaissance. His dedication to the art of the book ensured that his vision would reach far beyond the confines of elite patronage, contributing significantly to the visual culture of his era and beyond.