Domenico Campagnola stands as a significant, if sometimes overshadowed, figure of the Italian Renaissance, a versatile artist who excelled as a painter, engraver, and a pioneering printmaker. Active primarily in Venice and Padua, his work is emblematic of the Venetian School's rich colorito and its burgeoning interest in landscape as an independent genre. Though often discussed in relation to his adoptive father, Giulio Campagnola, and the towering figure of Titian, Domenico carved out his own distinct artistic identity, leaving a legacy that resonated through subsequent generations of European artists.

Enigmatic Beginnings and Formative Influences

The precise details of Domenico Campagnola's birth remain a subject of some scholarly debate. While many sources suggest he was born around 1500, possibly in Venice, others propose an earlier birth year, perhaps 1482, and some indicate Padua as his place of origin. It is generally accepted that he was of German parentage. His artistic journey began under the tutelage of his adoptive father, Giulio Campagnola, himself a highly accomplished engraver and painter. Giulio, known for his delicate stipple engravings and his association with figures like Giorgione, undoubtedly provided Domenico with a strong foundation in draftsmanship and the techniques of printmaking.

This familial and artistic bond with Giulio was crucial. From him, Domenico would have learned the intricacies of engraving and likely the emerging art of etching. Giulio's own interest in pastoral landscapes, often imbued with a Giorgionesque poetry, would have also been a formative influence on the young Domenico. The artistic environment of Venice and Padua in the early 16th century was vibrant and competitive, with masters like Giovanni Bellini having laid the groundwork for a new emphasis on color, light, and atmosphere.

The Venetian Crucible: Titian's Orbit and Artistic Development

Domenico Campagnola's career is inextricably linked with Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), the dominant force in Venetian painting for much of the 16th century. While the exact nature of their relationship – whether Domenico was a formal pupil or a workshop assistant – is not definitively clear, the profound impact of Titian's style on Campagnola's work is undeniable. Some accounts suggest that Domenico's precocious talent even provoked a degree of jealousy in the established master. This speaks volumes about the younger artist's capabilities.

Campagnola absorbed Titian's dynamic compositions, his rich and expressive use of color, and his ability to convey dramatic human emotion. This is evident in Campagnola's religious paintings and his figural studies. However, it was perhaps in the realm of landscape that Titian's influence, and Campagnola's subsequent innovation, was most keenly felt. Titian himself was increasingly incorporating expressive landscapes into his religious and mythological scenes, moving beyond the purely symbolic backdrops of earlier art. Campagnola would take this burgeoning interest a step further.

The artistic milieu of Venice at this time was a melting pot of influences. Besides Titian, artists like Giorgione, whose enigmatic and poetic works had a profound impact on the Venetian sensibility, Palma Vecchio, known for his sensuous figures and pastoral scenes, and Sebastiano del Piombo, who successfully blended Venetian color with Roman monumentality, all contributed to the rich artistic tapestry. Domenico Campagnola was working within this dynamic environment, absorbing, adapting, and ultimately forging his own path.

Pioneering the Independent Landscape

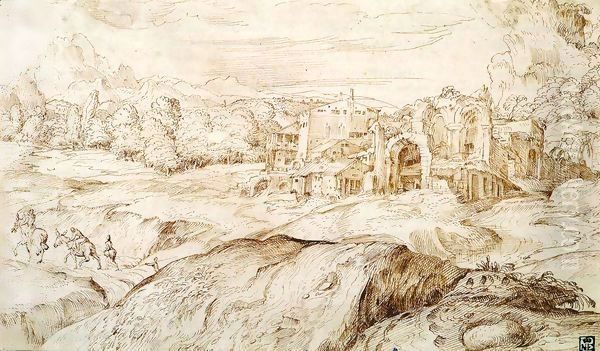

One of Domenico Campagnola's most significant contributions to art history was his role in the development of landscape as an independent genre. While landscapes had long served as backgrounds for narrative scenes, Campagnola was among the first artists, particularly in Venice, to create drawings and prints where the landscape itself was the primary subject. His panoramic vistas, often featuring rolling hills, distant mountains, rustic buildings, and sensitively rendered trees, were not mere topographical records but evocative portrayals of nature.

These landscapes, executed with a fluid, calligraphic line in his drawings and prints, captured a sense of atmosphere and space that was novel for the time. Works like his celebrated drawing, Mountainous Landscape with Antique Ruins, now in the Szépművészeti Múzeum, Budapest, exemplify this approach. Such pieces were revolutionary in that they were conceived and sold as finished works of art in their own right, sometimes even framed under glass, breaking the traditional hierarchy that privileged history painting. This elevation of landscape painting had a profound impact, paving the way for later masters of the genre across Europe.

His landscape drawings, often in pen and ink, display a remarkable facility and an understanding of natural forms. He skillfully used varying densities of line and hatching to create effects of light, shadow, and distance. These works were highly sought after by collectors and served as models for other artists. The influence of Northern European artists like Albrecht Dürer and Lucas van Leyden, who had already made significant strides in landscape depiction through their prints, can be discerned, but Campagnola infused his landscapes with a distinctly Italian, and specifically Venetian, sensibility.

Mastery in Printmaking: Woodcuts and Etchings

Domenico Campagnola was a prolific and innovative printmaker, working in both woodcut and etching. His woodcuts are particularly noteworthy. He often designed and, unusually for a painter of his stature at the time, sometimes cut his own woodblocks. This direct involvement in the block-cutting process allowed him a greater degree of control over the final image, resulting in prints that retained the spontaneity and vigor of his drawings. His woodcuts, such as those depicting rural festivals or biblical scenes set in expansive landscapes, are characterized by their bold lines and dynamic compositions.

Some of his woodcuts, particularly those with pastoral or mythological themes, show a clear debt to Titian's designs, and indeed, some were likely intended as interpretations or popularizations of Titian's ideas. However, Campagnola brought his own graphic sensibility to these works. He understood how to translate the tonal richness of Venetian painting into the black-and-white medium of the woodcut, using sophisticated systems of hatching and cross-hatching to suggest volume and atmosphere. His large-format woodcuts, such as the Battle of Naked Men in a Wood, demonstrate his ambition and skill in this medium.

While his output in etching was smaller than in woodcut, his etchings are of exceptionally high quality. Etching, a newer technique at the time, allowed for a finer and more fluid line, closer to drawing. His etching Adam and Eve, housed in the Pitti Palace, Florence, is a prime example of his skill in this medium, showcasing delicate modeling and a sensitive portrayal of the figures within a lush landscape. These prints, along with those of his adoptive father Giulio, and contemporaries like Marcantonio Raimondi (though Raimondi focused more on engraving after Raphael), contributed significantly to the dissemination of Renaissance imagery and artistic styles.

Frescoes and Monumental Works in Padua

Beyond his drawings and prints, Domenico Campagnola was also an accomplished painter of frescoes, primarily in Padua, where he spent a significant portion of his career. He received several important commissions for religious institutions, demonstrating his versatility and his ability to work on a large scale. His fresco cycles allowed him to combine his skills in figure painting with his talent for landscape, creating immersive narrative environments.

Among his most notable fresco projects are those for the Scuola del Carmine in Padua, where he painted scenes from the life of the Virgin, including a notable Meeting of Joachim and Anne and a Birth of the Virgin. He also executed significant frescoes in the Scuola di San Rocco and for the Church of Santa Maria dei Servi in Padua. These works, though some have suffered from the passage of time, reveal his command of complex compositions and his ability to integrate figures harmoniously within architectural or landscape settings.

In Padua, he also collaborated with other artists on decorative schemes, such as for the Council Hall. His work in fresco demonstrates his engagement with the broader traditions of Italian monumental painting, drawing on the legacy of artists like Giotto (whose Arena Chapel frescoes are in Padua) and Mantegna, while infusing his work with the characteristic warmth and dynamism of the Venetian school. His contemporary in Padua, Stefano Dall'Arzere, was another artist contributing to the city's artistic vibrancy, often working on similar large-scale decorative projects.

Artistic Style: Color, Light, and Lyrical Expression

Domenico Campagnola's artistic style is characterized by a synthesis of Venetian colorito and a lyrical, often pastoral, sensibility. Influenced by Titian, his paintings often feature warm, rich colors and a dynamic handling of light and shadow that creates a sense of volume and atmosphere. His figures, whether in religious narratives or mythological scenes, are imbued with a sense of vitality and emotional expressiveness.

In his drawings and prints, his line is fluid and energetic, capable of conveying both the monumentality of figures and the delicate textures of a landscape. He had a particular talent for depicting trees and foliage, rendering them with a sense of organic life. His landscapes, as previously noted, are not merely descriptive but are infused with a poetic quality, often evoking a sense of Arcadian harmony or, occasionally, a more dramatic, even tumultuous, vision of nature, as seen in his "earthquake fantasy" drawing.

His nudes, often featured in mythological or allegorical prints, demonstrate his understanding of human anatomy, though they are typically less idealized than those of the High Renaissance masters of Central Italy, retaining a Venetian earthiness. The overall impression of his work is one of robust energy combined with a sensitivity to the nuances of the natural world and human emotion. He shared with artists like Dosso Dossi of Ferrara an interest in imaginative and sometimes unconventional interpretations of classical and biblical themes, often set within richly imagined landscapes.

Notable Works and Their Significance

Several works stand out as particularly representative of Domenico Campagnola's artistic achievements and his contributions to Renaissance art.

His Mountainous Landscape with Antique Ruins (drawing, Szépművészeti Múzeum, Budapest) is a landmark in the history of landscape art, showcasing his ability to create a sweeping, panoramic vista that functions as an independent work of art. The interplay of natural forms and classical ruins evokes a sense of timelessness and the picturesque.

The woodcut Saint Jerome in the Wilderness is a powerful example of his printmaking, combining a dynamic portrayal of the penitent saint with a rugged, expressive landscape. The bold cutting and dramatic use of black and white create a strong visual impact, characteristic of his best work in this medium.

His frescoes in the Scuola del Carmine, Padua, such as The Meeting of Joachim and Anne, demonstrate his skill in narrative composition and his ability to convey tender human interaction within a well-defined spatial setting. These works highlight his importance as a painter of religious scenes in the Veneto.

The etching Adam and Eve (Pitti Palace, Florence) reveals his mastery of this more delicate printmaking technique, with its fine lines and subtle modeling, capturing the vulnerability and grace of the first humans in an idyllic landscape.

His numerous pen and ink landscape drawings, found in collections worldwide, such as the British Museum and the Louvre, are perhaps his most consistently admired works today. Their freedom of execution and evocative power continue to captivate viewers and attest to his innovative approach to depicting the natural world. These drawings often feature characteristic elements like rustic farmhouses, winding rivers, and feathery trees, all rendered with his distinctive calligraphic style.

Interactions and Collaborations

Domenico Campagnola was an active participant in the artistic life of Venice and Padua. His relationship with Titian, as discussed, was central, but he also interacted with other artists. His adoptive father, Giulio Campagnola, remained an important figure, and their styles, particularly in landscape prints, show a degree of mutual influence. It is plausible that Domenico assisted Giulio in his later years.

In Padua, he is known to have collaborated with other local artists on larger decorative projects. These collaborations were common in the Renaissance, allowing for the efficient completion of extensive commissions. Artists like Gualtiero Padovano and Stefano Dall'Arzere were among his contemporaries in Padua, contributing to the city's rich artistic output. The influence of earlier Paduan masters like Andrea Mantegna, with his emphasis on classical antiquity and sculptural form, would still have been palpable, though Campagnola's style remained firmly rooted in the Venetian tradition of color and light.

The printmaking world, in particular, fostered a network of artists, publishers, and collectors. Campagnola's prints, like those of Dürer, Lucas van Leyden, and Marcantonio Raimondi, circulated widely, facilitating the exchange of artistic ideas across geographical boundaries. This network helped to establish Venice as a major center for print production in the 16th century.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Domenico Campagnola died in Padua in 1564, leaving behind a substantial body of work that significantly impacted the course of European art, particularly in the realm of landscape and printmaking. His innovations in treating landscape as an independent subject were crucial for its subsequent development. Artists of the Netherlandish school, such as Pieter Bruegel the Elder, who visited Italy, would have been aware of the Venetian tradition of landscape representation, to which Campagnola was a key contributor. Bruegel's own panoramic landscapes share a similar ambition in capturing the breadth and diversity of the natural world.

Later landscape painters, both in Italy and Northern Europe, built upon the foundations laid by artists like Campagnola. The pastoral landscapes of Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin in the 17th century, while developing in new directions, owe a debt to the Renaissance pioneers who first explored the expressive potential of landscape. Even artists like Annibale Carracci, one of the founders of the Baroque style in Rome, showed an interest in landscape that can be traced back to Venetian precedents.

Campagnola's prints had a long afterlife, collected and studied by artists for generations. The French Rococo painter Jean-Antoine Watteau, for instance, is known to have owned and copied drawings by Campagnola, drawn to their rustic charm and fluid draftsmanship. This demonstrates the enduring appeal of Campagnola's vision of nature. His technical innovations in woodcut, particularly his direct involvement in the cutting process, also set a precedent for later artists who sought greater control over their printed images.

While he may not have achieved the same level of fame as his contemporary Titian, or later Venetian giants like Tintoretto or Paolo Veronese, Domenico Campagnola's contributions were vital. He was a bridge figure, absorbing the lessons of the High Renaissance and pointing the way towards new artistic possibilities, especially in the depiction of the natural world. His work remains a testament to the richness and diversity of the Venetian Renaissance and its lasting impact on Western art. His dedication to landscape helped to elevate its status, ensuring it would become one of the most beloved and enduring genres in European painting.

Conclusion: An Artist of Versatility and Vision

Domenico Campagnola emerges from the historical record as an artist of considerable talent, versatility, and foresight. His ability to move fluidly between painting, drawing, and the various techniques of printmaking marks him as a quintessential Renaissance man of the arts. His deep engagement with the Venetian tradition, particularly the influence of Titian, provided a rich foundation for his work, but he was no mere imitator.

His most profound legacy lies in his pioneering efforts to establish landscape as a worthy subject in its own right. Through his evocative drawings and prints, he captured the beauty and poetry of the Veneto countryside, influencing countless artists who followed. His technical skill in woodcut and etching further solidified his reputation and ensured the wide dissemination of his artistic vision. Though the details of his early life may be debated, the impact of his mature work is undeniable, securing Domenico Campagnola an important place in the annals of Italian Renaissance art.