Józef Marian Chełmoński stands as one of the most significant and beloved figures in the history of Polish art. Active during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a period of profound national challenge and artistic transformation, Chełmoński became a leading exponent of Realism in Poland. His powerful and evocative depictions of the Polish landscape, rural life, and particularly his dynamic portrayals of horses, captured the spirit of the nation and continue to resonate with audiences today. His work is intrinsically linked to the so-called "Polish Patriotic Painting" movement, celebrating the beauty and resilience of his homeland during a time when Poland did not exist as an independent state on the map of Europe.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Warsaw

Józef Chełmoński was born on November 7, 1849, in the village of Boczki, near Łowicz, in central Poland. This region, then part of the Russian Empire following the partitions of Poland, deeply shaped his artistic vision. His family belonged to the minor nobility (szlachta), and his father served as a village administrator and lessee of the Boczki estate. This upbringing immersed the young Chełmoński in the rhythms of rural life, the vast landscapes of Mazovia, and the close relationship between people, animals, and the land – themes that would dominate his artistic career.

His formal artistic education began in Warsaw, where he attended the Warsaw Drawing Class (Klasa Rysunkowa) between 1867 and 1871. This institution was a vital center for artistic training in Russian-controlled Poland. Crucially, during this period, Chełmoński also took private lessons from Wojciech Gerson, a towering figure in Polish art. Gerson was a prominent history painter but also a dedicated landscape artist and a key proponent of Realism in Poland. He instilled in his students the importance of direct observation from nature and a commitment to depicting Polish subjects. Gerson's influence is visible in Chełmoński's early works, particularly in his developing sensitivity to landscape and atmosphere.

Even in these formative years, Chełmoński began to gravitate towards genre scenes and landscapes, departing somewhat from the historical subjects favored by Gerson. He was drawn to the everyday life of the Polish countryside, its inhabitants, and its wildlife. His early sketches and paintings already showed a keen eye for detail and a burgeoning ability to capture the specific character of the Polish environment. This period laid the essential groundwork for his later artistic development, grounding his art in the direct experience of his native land.

The Munich Years: A Crucible of Polish Realism

Seeking broader artistic horizons, Chełmoński moved to Munich in 1871, remaining there until 1874. Munich was, at that time, a major European art center, rivaling Paris, and particularly attractive to artists from Central and Eastern Europe, including many Poles. The Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Munich offered rigorous training, but perhaps more important was the vibrant community of Polish artists who gathered there, forming an informal "Munich School" of Polish painting.

At the Academy, Chełmoński studied briefly under Hermann Anschütz and Alexander Strähuber, absorbing the technical proficiency emphasized by the German academic tradition. However, his most significant interactions were with fellow Polish painters. He became closely associated with the circle around Józef Brandt and the highly talented Maksymilian Gierymski. Brandt was already gaining renown for his dramatic scenes of Cossack life and Polish history, often featuring horses, while Maksymilian Gierymski was a master of atmospheric landscapes and scenes of the 1863 January Uprising.

This Munich period was transformative for Chełmoński. He was exposed to contemporary European art trends, particularly the prevailing Realism. The environment fostered a spirit of artistic camaraderie and critical discussion among the Poles, who debated how to reconcile international styles with distinctly Polish themes and sensibilities. Chełmoński's style matured rapidly, gaining confidence and dynamism. He began producing works that garnered attention, focusing on Polish and Ukrainian landscapes, hunting scenes, and his signature subject: horses depicted with incredible energy and anatomical accuracy. His palette brightened, and his brushwork became more assured, capturing movement and atmosphere with growing skill.

Parisian Success and International Recognition

In 1875, Chełmoński made a pivotal move to Paris, the undisputed capital of the 19th-century art world. He arrived with letters of recommendation and quickly sought to establish himself. Paris offered exposure to the latest artistic currents, including the burgeoning Impressionist movement, although Chełmoński remained fundamentally committed to Realism. He exhibited regularly at the prestigious Paris Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts.

His paintings, particularly those featuring dramatic horse-drawn sleighs, galloping steeds across the vast plains (often inspired by his travels to Ukraine), and vivid hunting scenes, found favor with the Parisian public and critics. These works possessed an exoticism and raw energy that appealed to French tastes. He gained considerable fame and financial success, with his works being sought after by dealers and collectors. A highlight of his international career was winning the Grand Prix at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1889, a testament to his established reputation.

During his time in Paris, which lasted over a decade, Chełmoński maintained connections with the Polish artistic community there. He was acquainted with figures like Stanisław Witkiewicz, a painter, influential art critic, and creator of the Zakopane Style, and Adam Chmielowski (later Saint Albert), another painter associated with the Munich circle who eventually abandoned art for religious life. Despite his success abroad, Chełmoński's subject matter remained deeply rooted in his Polish and Ukrainian experiences. His Parisian works often convey a sense of nostalgia for the landscapes and life he had left behind, imbued with a powerful, almost elemental energy.

The Essence of Chełmoński's Realism

Chełmoński's art is firmly situated within the Realist movement, which sought to depict subjects truthfully, without artificiality or idealization, often focusing on contemporary life and the natural world. However, his Realism was not merely a detached, objective recording of reality. It was infused with a deep emotional connection to his subjects and a palpable sense of atmosphere. He shared with the French Barbizon School painters, such as Jean-François Millet and Théodore Rousseau, a profound respect for nature and rural life, although his style developed independently, shaped more directly by his Polish roots and the Munich experience.

His commitment to observation was paramount. He spent countless hours sketching outdoors, studying the effects of light and weather, the anatomy and movement of animals, and the specific details of the landscape. This dedication is evident in the convincing textures of snow, mud, or dusty roads, the accurate rendering of wildlife, and the authentic portrayal of peasant life. He avoided sentimentalizing his subjects, presenting the harshness and beauty of rural existence with equal honesty.

A defining characteristic of Chełmoński's work is its dynamism. He possessed an extraordinary ability to capture movement, particularly evident in his depictions of horses. Whether pulling a peasant cart, racing across the steppe in a 'czwórka' (four-in-hand), or struggling through snow, his horses are rendered with breathtaking energy and anatomical precision. This dynamism extends to his landscapes, which often convey the power of nature – the wind sweeping across vast plains, an impending storm, or the stillness of a winter's day. His brushwork, often vigorous and expressive, contributes significantly to this sense of vitality.

Masterpieces of the Polish Landscape

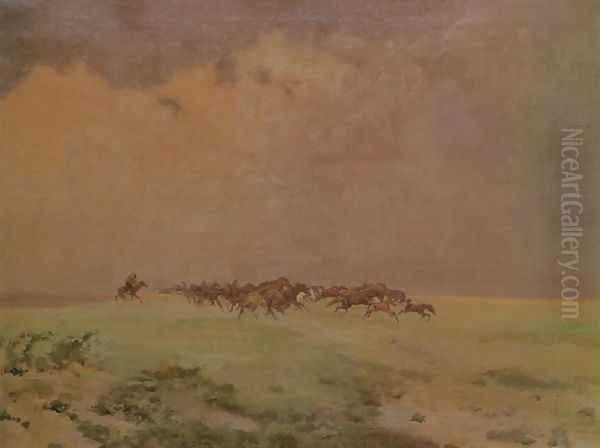

Chełmoński's oeuvre includes numerous iconic works that have become embedded in Polish national consciousness. Among his most celebrated paintings is Czwórka (Four-in-Hand, also known as Tarantass on the Ukrainian Steppe), painted during his successful Paris period. This large canvas depicts four horses galloping at full speed, pulling a carriage across a seemingly endless, muddy plain under a dramatic sky. The painting is a tour-de-force of movement, capturing the raw power of the animals and the vastness of the landscape with incredible energy. It evokes the spirit of the wild Eastern borderlands.

Another beloved masterpiece is Babie Lato (Indian Summer), painted in 1875. This work presents a stark contrast in mood. It depicts a young peasant girl lying barefoot in a sun-drenched autumn field, idly playing with gossamer threads floating in the air. Behind her stretches a flat, typically Mazovian landscape under a hazy sky. The painting is imbued with a sense of tranquility, nostalgia, and a subtle connection between the human figure and the natural world. It captures a fleeting moment of warmth and beauty before the onset of winter, rendered with delicate sensitivity to light and atmosphere.

Bociany (Storks), painted in 1900 during his later period after returning to Poland, is another quintessential Chełmoński work. It shows a peasant farmer and his son pausing their plowing to watch a flock of storks circling overhead against a luminous sky. Storks hold a special place in Polish folklore as symbols of spring, good fortune, and the homeland. The painting combines realistic observation of agricultural life and bird behavior with a deeper symbolic resonance, celebrating the enduring connection between the Polish people and their land.

Kuropatwy na śniegu (Partridges on the Snow), painted in 1891, exemplifies Chełmoński's skill as a wildlife painter and his ability to capture the stark beauty of the Polish winter. A covey of partridges blends almost perfectly with the snow-covered field, their forms rendered with meticulous detail against the muted tones of the winter landscape. The painting is a quiet yet powerful study of survival and camouflage in nature, showcasing the artist's intimate knowledge of the natural world gained through direct observation. Other notable works include Przed burzą (Before the Storm), Powrót z pola (Return from the Fields), and numerous dynamic hunting scenes.

Return to Poland: The Kuklówka Years

Despite his international success, Chełmoński felt an increasing pull towards his homeland. In 1889, the same year he won the Grand Prix in Paris, he decided to return to Poland permanently. He purchased a small manor house in the village of Kuklówka Zarzeczna, not far from Warsaw. This move marked a significant shift in his life and, to some extent, his art. He distanced himself from the bustling art capitals and immersed himself once again in the rural environment that had always been his primary inspiration.

Life in Kuklówka allowed Chełmoński to live in close harmony with nature. He continued to paint prolifically, drawing inspiration directly from his surroundings. His works from this later period often possess a calmer, more contemplative quality compared to the dramatic canvases of his Paris years. He focused intently on the changing seasons, the local wildlife (birds became a particularly frequent subject), and the quiet rhythms of village life. Paintings like Storks and Partridges on the Snow belong to this mature phase.

He remained a respected figure in the Polish art world, although he lived somewhat reclusively. His home in Kuklówka became a haven where he could fully dedicate himself to observing and painting the subjects he loved most. This period solidified his image as an artist deeply connected to the Polish soil, whose work served as an authentic reflection of the national landscape and spirit. Józef Chełmoński died in Kuklówka on April 6, 1914, just before the outbreak of World War I, and was buried in the nearby cemetery in Ojrzeń.

Artistic Influences and Connections

Chełmoński's artistic journey was shaped by various influences and interactions. His initial training under Wojciech Gerson provided a solid foundation in Realism and a focus on Polish themes. The Munich period was crucial, exposing him to broader European trends and fostering connections with key figures of the Polish Munich School, notably Józef Brandt and Maksymilian Gierymski. The dynamic realism and thematic interests of these artists undoubtedly spurred his own development. He would also have been aware of the work of Maksymilian's brother, Aleksander Gierymski, another significant Polish Realist.

While in Paris, although he didn't adopt their style, he was certainly aware of the Impressionists and their focus on light and contemporary life. His own Realism, however, remained closer in spirit to the Barbizon School's reverence for nature, exemplified by painters like Jean-François Millet, whose depictions of peasant life resonated with Chełmoński's own interests. He also maintained contact with Polish intellectuals and artists like Stanisław Witkiewicz and Adam Chmielowski.

Within the broader context of Polish art, Chełmoński's work can be seen as a continuation and evolution of the landscape and genre traditions. He built upon the foundations laid by earlier artists but brought a new level of dynamism and atmospheric intensity to his subjects. While distinct from the grand historical narratives of Jan Matejko or the tragic patriotism of Artur Grottger, Chełmoński's celebration of the Polish land and its people served a similar purpose in affirming national identity during the partitions. His focus on nature also connects him to earlier Polish artists known for animal studies, like the Romantic painter Piotr Michałowski.

Legacy and Enduring Appeal

Józef Chełmoński holds an undisputed place as one of Poland's most important and popular painters. His work represents a high point of Polish Realism in the late 19th century. He masterfully captured the specific character of the Polish landscape – its vast plains, dramatic skies, and distinct seasons – and the life of its rural inhabitants and wildlife. His ability to convey movement, atmosphere, and the raw energy of nature, particularly in his depictions of horses, remains unparalleled in Polish art.

His paintings resonated deeply with Polish society during the partitions, offering a powerful affirmation of national identity through the celebration of the homeland's beauty and resilience. This "patriotic" dimension, rooted in the love of the land rather than overt political statements, contributed significantly to his enduring popularity. Even today, his works evoke a strong sense of connection to Polish nature and tradition. He influenced subsequent generations of Polish landscape painters, including figures associated with the Young Poland movement like Leon Wyczółkowski and Julian Fałat, although they incorporated newer stylistic elements like Impressionism and Symbolism.

Chełmoński's major works are proudly displayed in Poland's leading museums, including the National Museum in Warsaw, the National Museum in Kraków (at the Sukiennice Gallery), and the National Museum in Poznań. His paintings are consistently among the most admired exhibits, drawing crowds and appearing frequently in reproductions. In recognition of his significance, a monument dedicated to the artist was erected in Grodzisk Mazowiecki, near his final home in Kuklówka. His legacy endures not just in museums, but in the collective cultural memory of Poland, where he is revered as the painter who captured the soul of the Polish landscape.

Conclusion: The Painter of the Polish Soul

Józef Chełmoński's contribution to Polish art is immense. As a leading figure of Realism, he brought an unparalleled dynamism and atmospheric depth to the depiction of his homeland. From the energetic Czwórka racing across the steppe to the tranquil Babie Lato and the symbolic Bociany, his paintings captured the diverse moods and essential character of the Polish landscape and rural life. His mastery in depicting horses and wildlife, combined with his profound connection to nature, resulted in works that are both technically brilliant and emotionally resonant. Living and working through a challenging period in Polish history, Chełmoński's art became a powerful expression of national identity, celebrating the enduring spirit of the land and its people. His legacy continues to inspire, making him one of the most cherished artists in the Polish canon.