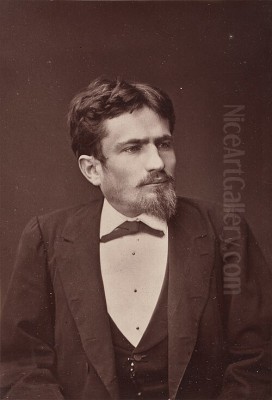

Jules Arsène Garnier stands as a notable figure in the landscape of nineteenth-century French art. Born in Paris on January 22, 1847, and passing away in the same city on December 25, 1889, Garnier's relatively short life coincided with a period of immense artistic ferment and transformation in France. He carved out a niche for himself as a painter of historical genre scenes, often imbued with a dramatic, anecdotal, and sometimes provocative character. While not an avant-garde revolutionary, Garnier was a skilled practitioner within the academic tradition, whose works appealed to a public fascinated by vivid reconstructions of the past and explorations of human passion.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Jules Arsène Garnier's artistic journey began with formal training, essential for any aspiring painter in the highly structured French art world of the time. His initial studies took place in Toulouse, a significant regional art center, commencing around 1865. This foundational education would have provided him with the basic skills in drawing, composition, and an understanding of art history, preparing him for the more rigorous environment of the capital.

In 1867, Garnier made the pivotal move to Paris to enter the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts. This institution was the bastion of academic art in France, shaping generations of artists according to classical ideals and meticulous technique. Crucially, he became a pupil of Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904), one of the most influential and successful academic painters of the era. Gérôme was renowned for his highly polished historical scenes, Orientalist subjects, and almost photographic realism. His studio was a magnet for aspiring artists, and his tutelage would have profoundly impacted Garnier's artistic development.

Under Gérôme, Garnier would have honed his skills in anatomical accuracy, detailed rendering of textures and costumes, and the construction of complex narrative compositions. Gérôme's own penchant for dramatic historical moments, often with a touch of the exotic or the violent, likely resonated with Garnier's own inclinations. The emphasis on historical research to ensure authenticity in settings and attire, a hallmark of Gérôme's work, would also have been instilled in his students, including Garnier.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

Jules Arsène Garnier's artistic output is characterized by its focus on historical genre painting. He predominantly chose subjects from medieval and Renaissance history, periods rich in dramatic events, colorful personalities, and distinct social customs that offered ample material for narrative art. His style remained largely within the academic tradition, emphasizing clear storytelling, careful composition, and a high degree of finish.

A distinguishing feature of Garnier's work was his tendency towards the anecdotal and the sensational. He was not afraid to tackle themes that were risqué, violent, or morally ambiguous, which sometimes led to his work being described as exaggerated or even "indecent" by contemporary critics. This willingness to explore the more dramatic, and occasionally lurid, aspects of history set him apart from some of his more staid academic contemporaries. His paintings often aimed to elicit a strong emotional response from the viewer, whether it be amusement, shock, or pathos.

In terms of technique, Garnier demonstrated a fine handling of color and a keen understanding of light and shadow to create mood and volume. His figures were generally well-drawn, and he paid considerable attention to the details of costume, architecture, and accessories, reflecting the academic emphasis on historical verisimilitude. While the broader art world was being revolutionized by Impressionism and its focus on fleeting moments and subjective perception, Garnier remained committed to a more traditional, narrative-driven approach. His paintings were meant to be "read" as much as seen, with gestures, expressions, and settings all contributing to the unfolding story.

Key Works and Salon Career

The Paris Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, was the primary venue for artists to display their work and gain recognition in the nineteenth century. Jules Arsène Garnier was a regular participant, and his Salon entries provide a good overview of his thematic interests and stylistic development.

One of his early notable works was Mlle de Sombreuil, exhibited at the Salon of 1870. This painting likely depicted a scene from the French Revolution involving Mademoiselle de Sombreuil, who famously saved her father's life during the September Massacres by drinking a goblet of blood. Such a subject, combining historical drama with a frisson of horror, was typical of the kind of themes that attracted Garnier. The work reportedly received mixed reviews, a common fate for artists tackling challenging or unconventional subjects.

Another significant painting is Le Supplice des Adultères (The Punishment of Adulterers). This work, true to its title, would have depicted a scene of moral retribution, a theme that had a long history in art but which Garnier likely approached with his characteristic flair for drama and perhaps a degree of sensationalism. Such subjects allowed for the depiction of strong emotions and often involved dynamic figure compositions.

His 1887 painting, Fête champêtre (Pastoral Festival), measuring 106.7 x 167 cm and currently in a private collection, suggests a slightly different vein, perhaps a more idyllic or celebratory scene, though even in such subjects, Garnier might have introduced an underlying narrative tension or social commentary. The term "fête champêtre" itself evokes a tradition of outdoor leisure scenes popularized by artists like Antoine Watteau (1684-1721) and later revisited by many, including the Impressionists, albeit in a very different style. Garnier's interpretation would have been filtered through his academic lens and historical focus.

Other works attributed to him, such as The Bath and The Dream of Trajan, both reportedly from 1869, further indicate his interest in classical and historical themes, allowing for explorations of the human form and grand historical narratives. Le Droit du Seigneur (The Lord's Right), also known as Le Rapt (The Abduction), is another of his well-known, and controversial, works, tackling a feudal custom that was both historically debated and inherently dramatic and exploitative. Similarly, Le Roi s'amuse (The King Amuses Himself), likely inspired by Victor Hugo's play of the same name (which also formed the basis for Verdi's opera Rigoletto), would have offered rich opportunities for depicting courtly intrigue and moral decay.

Garnier's consistent participation in the Salon indicates his ambition and his engagement with the official art system. Success at the Salon could lead to state purchases, private commissions, and critical acclaim, all vital for an artist's career.

The Parisian Art World of the Late Nineteenth Century

To fully appreciate Jules Arsène Garnier's career, it is essential to understand the vibrant and often contentious art world of Paris in the latter half of the nineteenth century. This era was marked by the entrenched power of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, which dictated artistic taste and controlled access to the prestigious Salon. Academic painters like Garnier's teacher, Jean-Léon Gérôme, along with figures such as William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825-1905) and Alexandre Cabanel (1823-1889), represented the pinnacle of official success. Their work, characterized by technical polish, idealized forms, and often mythological or historical subjects, was favored by collectors and the state.

However, this period also witnessed the rise of powerful counter-movements. Realism, championed by Gustave Courbet (1819-1877) and Jean-François Millet (1814-1875), had already challenged academic conventions by focusing on contemporary life and the depiction of ordinary people. Following this, Impressionism emerged in the 1870s as a radical departure from academic norms. Artists like Claude Monet (1840-1926), Edgar Degas (1834-1917), Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), and Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919) rejected the smooth finish and historical subjects of academic art in favor of capturing fleeting moments, the effects of light and atmosphere, and scenes of modern Parisian life, often painting en plein air.

The Salon des Refusés in 1863, which exhibited works rejected by the official Salon jury, including Édouard Manet's (1832-1883) controversial Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe, marked a turning point, highlighting the growing dissatisfaction with academic exclusivity. Despite the rise of these independent movements, the official Salon remained a powerful institution, and many artists, including Garnier, continued to work within its framework, seeking recognition through established channels.

Garnier's choice of historical genre, often with a dramatic or sensationalist twist, can be seen as a way to engage a public that was increasingly exposed to diverse forms of visual culture, including popular prints, illustrated journals, and photography. His narrative clarity and detailed execution appealed to a taste for storytelling, while his sometimes provocative themes offered a frisson of excitement. He operated in a space between the high-minded historical paintings of some academicians and the everyday subjects of the Impressionists, focusing on historical anecdotes that could be both entertaining and thought-provoking. Other painters exploring historical narratives with dramatic intensity included Jean-Paul Laurens (1838-1921), known for his stark depictions of medieval and papal history. In England, Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836-1912) was achieving immense popularity with his meticulously researched scenes of classical antiquity, demonstrating a widespread contemporary interest in historical genre.

Specific Influences and Artistic Choices

The most significant artistic influence on Jules Arsène Garnier was undoubtedly his master, Jean-Léon Gérôme. Gérôme's meticulous attention to detail, his polished surfaces, and his penchant for dramatic, often historically-grounded narratives, provided a clear model for Garnier. Gérôme's success in depicting scenes from Roman antiquity, Greek mythology, and the contemporary Middle East (Orientalism, a genre also explored by artists like Eugène Fromentin (1820-1876) and Gustave Guillaumet (1840-1887)) demonstrated the appeal of well-researched, vividly rendered historical and exotic subjects. Garnier adapted this approach primarily to European historical settings.

The nineteenth century saw a widespread fascination with history, fueled by Romantic literature, archaeological discoveries, and a growing sense of national identity. This historical revivalism manifested in various forms of art, architecture, and design. Garnier tapped into this interest, choosing moments from the past that allowed for rich visual storytelling. His selection of themes often leaned towards the more turbulent or morally complex aspects of history, suggesting an interest in human psychology and social dynamics, albeit presented through a historical lens.

His choice of subjects that were sometimes considered "indecent" or overly sensational can be interpreted in several ways. It could reflect a genuine artistic interest in exploring the extremes of human behavior, or it might have been a calculated strategy to attract attention in the crowded Salon exhibitions. A "succès de scandale" (success through scandal) was not unknown in the art world, and a painting that provoked discussion, even negative, was often more memorable than one that was merely competent but unremarkable. Artists like Gustave Doré (1832-1883), though primarily an illustrator and sculptor, also explored dramatic and fantastical themes that captivated the public imagination.

Garnier's commitment to narrative clarity distinguished his work from the emerging Impressionist focus on visual sensation over storytelling. While the Impressionists sought to capture the fleeting moment, Garnier aimed to reconstruct a past event with as much vividness and detail as possible, inviting the viewer to engage with the story being told. This approach aligned him with a long tradition of history painting, but his focus on more intimate, anecdotal scenes rather than grand, heroic narratives placed him more specifically within the category of historical genre.

Anecdotes and Personal Details

Specific, verifiable anecdotes about Jules Arsène Garnier's personal life or studio practice are less widely documented than those of some of his more famous contemporaries or, indeed, than those of the architect Charles Garnier (1825-1898), with whom he is sometimes confused due to their shared surname and contemporaneity in Paris. Charles Garnier, the designer of the opulent Palais Garnier (the Paris Opera House), was a major public figure whose work and life generated considerable discussion and documentation, including collaborations with artists like Paul Baudry (1828-1886) for the ceiling paintings and Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux (1827-1875) for sculptures like "La Danse."

For Jules Arsène Garnier, the painter, his biography is primarily traced through his artistic education, his Salon entries, and the nature of his works. The critical reception of his paintings, such as the mixed reviews for Mlle de Sombreuil, offers glimpses into how his art was perceived. The characterization of some of his themes as "indecent" suggests he was an artist who was willing to push boundaries, or at least to cater to a taste for the mildly scandalous. His dedication to his craft is evident in the consistent production of detailed and complex narrative paintings for the Salons over his career.

The Legion of Honour awarded to him late in his life indicates a degree of official recognition for his contributions to French art, even if he did not achieve the same level of fame as the leading academic masters or the groundbreaking Impressionists. His relatively early death at the age of 42 cut short a career that was still actively developing.

Collaboration and Competition

The art world of nineteenth-century Paris was intensely competitive. Artists vied for places in the École des Beaux-Arts, for the attention of influential teachers like Gérôme, for acceptance into the Salon, and for medals, state purchases, and private commissions. Jules Arsène Garnier would have been fully immersed in this competitive environment. His success in regularly exhibiting at the Salon demonstrates his ability to meet the prevailing standards of technical skill and compositional ability.

Direct collaborations between painters of Garnier's type were less common than, for example, an architect commissioning painters and sculptors for a large building project (as Charles Garnier did for the Opera). Competition, however, was inherent in the Salon system. Garnier would have been competing for wall space and critical attention not only with established masters but also with a multitude of other aspiring artists.

The mention of Etienne Barthélemy Garnier (1759-1849) in some contexts related to Jules Arsène Garnier can be confusing. Etienne Barthélemy Garnier was a history painter from a much earlier generation, active during the Neoclassical and early Romantic periods. Any "competition" between him and Jules Arsène Garnier would not have been direct due to the significant chronological gap. However, the existence of multiple artists named Garnier underscores the need for careful differentiation.

Jules Arsène Garnier's competition would have been with his direct contemporaries working in similar veins of historical or genre painting. Artists who specialized in dramatic historical narratives, or those who, like him, sometimes courted controversy with their subject matter, would have been his natural rivals for public and critical attention. The pursuit of honors, such as the Legion of Honour, was another arena of competition, signifying official validation of an artist's career.

Later Career, Recognition, and Legacy

Jules Arsène Garnier continued to produce and exhibit his work throughout the 1870s and 1880s. His dedication to his craft and his consistent presence at the Paris Salon solidified his reputation as a skilled painter of historical genre scenes. The culmination of his official recognition came in 1889, the year of his death, when he was made a Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur (Knight of the Legion of Honour). This prestigious award acknowledged his contributions to French art and marked him as an artist of standing within the established art system.

His relatively early death at the age of 42 meant that his oeuvre, while substantial, did not span the many decades that allowed some of his contemporaries to evolve their styles further or achieve even greater fame. Nevertheless, he left behind a body of work that provides a fascinating window into the tastes and preoccupations of a segment of the nineteenth-century art public.

In evaluating Jules Arsène Garnier's position in art history, he is generally regarded as a competent and interesting academic painter who specialized in a particular niche of historical narrative. He was not an innovator in the league of the Impressionists or Post-Impressionists like Paul Cézanne (1839-1906) or Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), who fundamentally altered the course of Western art. Nor did he achieve the towering status of academic giants like his teacher Gérôme or Bouguereau. However, his work is representative of a significant strand of nineteenth-century painting that valued storytelling, historical detail, and dramatic effect.

His influence on subsequent art was likely limited. The academic tradition itself, while continuing to produce skilled artists, was increasingly overshadowed by modernist movements in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Artists like Garnier, who adhered to narrative and a high degree of finish, found their style becoming less fashionable as new artistic priorities emerged. However, there has been a renewed art historical interest in academic painting in recent decades, leading to a more nuanced appreciation of artists like Garnier who were successful and respected in their own time. His paintings are still valued for their technical skill, their engaging (if sometimes sensational) subject matter, and their reflection of nineteenth-century historicism.

The critical reception of his work during his lifetime, as evidenced by reviews of pieces like Mlle de Sombreuil, suggests that he was an artist who provoked a response, which is often a sign of a work's vitality. While some might have found his themes too strong or his style too exaggerated, others were undoubtedly drawn to the vividness and drama of his historical reconstructions.

Conclusion

Jules Arsène Garnier was a distinctive voice in the chorus of nineteenth-century French painting. A product of the rigorous academic training of the École des Beaux-Arts and the studio of Jean-Léon Gérôme, he dedicated his career to the depiction of historical genre scenes. His paintings, often set in medieval or Renaissance Europe, are characterized by their narrative richness, attention to detail, and a penchant for dramatic, sometimes provocative, themes. He skillfully navigated the competitive Parisian art world, regularly exhibiting at the Salon and eventually earning the Legion of Honour.

While the avant-garde movements of his time, particularly Impressionism, were forging new paths that would dominate the future of art, Garnier and other academic painters continued to cater to a significant public appetite for well-crafted, story-driven art. His work offers a glimpse into a world fascinated by history, human drama, and the visual spectacle of the past. Though perhaps not a household name today in the same way as some of his revolutionary contemporaries like Monet or Degas, or even his own master Gérôme, Jules Arsène Garnier remains an intriguing figure whose art reflects both the strengths of the academic tradition and the particular cultural currents of his era. His paintings serve as a reminder of the diverse artistic landscape of the nineteenth century and the many ways in which artists sought to capture and interpret the human experience.