Vasily Ivanovich Surikov stands as one of the most formidable figures in the annals of Russian art, a painter whose monumental canvases brought the tumultuous and dramatic history of his nation to vivid, unforgettable life. Born on January 24, 1848, in the remote Siberian city of Krasnoyarsk, Surikov's art was deeply imbued with the spirit of his homeland, its people, and its epic past. He became a leading exponent of historical realism, capturing pivotal moments with an unparalleled psychological depth and a masterful command of composition and color. His legacy is not merely that of a skilled technician, but of a profound visual storyteller who shaped Russia's understanding of its own identity.

Siberian Roots and Early Stirrings

Surikov's origins were intrinsically linked to the pioneering spirit and rugged character of Siberia. He hailed from a family of Don Cossacks whose ancestors had ventured into Siberia with Yermak Timofeyevich, the legendary conqueror, in the 16th century. This heritage provided a deep wellspring of inspiration throughout his career, instilling in him a fascination with strong characters, dramatic conflicts, and the sweeping narratives of Russian history. His childhood in Krasnoyarsk, a city surrounded by the vast, untamed Siberian landscape, further shaped his artistic vision, lending a raw, elemental power to his later works.

The young Surikov displayed an early aptitude for drawing, his talent nurtured by a local teacher, Nikolai Grebnev. However, the path to formal artistic training was not straightforward. His family, while respected, faced financial constraints, particularly after the death of his father when Vasily was still a boy. For a time, he worked as a clerk to support his family, but the dream of pursuing art remained undiminished.

The Journey to St. Petersburg and Academic Foundations

The turning point came with the support of Pyotr Kuznetsov, a wealthy Krasnoyarsk gold-mine owner and philanthropist who recognized Surikov's exceptional talent. Kuznetsov sponsored Surikov's journey to St. Petersburg in 1868, with the goal of enrolling in the prestigious Imperial Academy of Arts. His initial attempt to enter the Academy was unsuccessful, but Surikov was undeterred. He spent several months studying at the drawing school of the Society for the Encouragement of Artists, honing his skills.

In 1869, Surikov successfully passed the entrance examinations and was admitted to the Imperial Academy of Arts. There, he studied under the tutelage of renowned artists, most notably Pavel Chistyakov, a highly influential teacher known for his rigorous academic methods and his emphasis on drawing and anatomical accuracy. Chistyakov's pedagogy profoundly impacted many leading Russian artists of the time, including Ilya Repin, Valentin Serov, and Mikhail Vrubel. Surikov proved to be a diligent student, absorbing the academic principles while already beginning to forge his own distinctive path. His student works, such as "View of the Monument to Peter I on Senate Square in St. Petersburg" (1870) and "The Good Samaritan" (1874), demonstrated his growing technical proficiency and his burgeoning interest in dramatic narrative.

Upon graduating in 1875, Surikov received a commission that signaled his early promise: to paint murals for the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow. This project, depicting scenes from the Ecumenical Councils, provided him with invaluable experience in creating large-scale compositions and further immersed him in historical and religious themes. Though these murals were executed in a more traditional, academic style, they laid the groundwork for the monumental historical canvases that would define his career.

The Great Historical Epics

After settling in Moscow in 1877, Surikov embarked on the series of large-scale historical paintings that would secure his fame. He moved away from purely religious or mythological subjects to tackle pivotal, often tragic, moments in Russian history, imbuing them with a sense of immediacy and profound human drama. He became associated with the Peredvizhniki (the Wanderers or Itinerants), a group of realist artists who broke away from academic conventions to depict contemporary life and Russian history with a critical and often nationalistic perspective. Though not formally a member for his entire career, he exhibited with them and shared many of their artistic and social concerns. Key figures in this movement included Ivan Kramskoy, Ilya Repin, Vasily Perov, Ivan Shishkin, and Alexei Savrasov.

The Morning of the Streltsy Execution

Completed in 1881, "The Morning of the Streltsy Execution" was Surikov's first major historical masterpiece and announced his arrival as a powerful new voice in Russian art. The painting depicts the grim aftermath of the Streltsy uprising of 1698 against Tsar Peter the Great. Rather than focusing on the executions themselves, Surikov captures the tense, emotionally charged moments before the event, on a bleak Moscow morning in Red Square, with St. Basil's Cathedral looming in the background.

The canvas is a tour-de-force of psychological portraiture and crowd composition. The Streltsy, defiant and stoic in the face of death, are contrasted with their grieving families and the impassive figure of Peter the Great on horseback, observing the scene with cold determination. Each face in the crowd tells a story of anguish, despair, or unyielding resistance. Surikov's meticulous attention to historical detail in clothing, architecture, and weaponry, combined with his ability to convey the raw emotional power of the moment, made the painting a sensation. Artists like Ilya Repin, known for his own historical and social realist works such as "Barge Haulers on the Volga" and "Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan," recognized the profound impact of Surikov's vision.

Menshikov in Beryozovo

Two years later, in 1883, Surikov completed "Menshikov in Beryozovo." This painting portrays Prince Alexander Menshikov, once Peter the Great's closest confidant and one of the most powerful men in Russia, now exiled to the remote Siberian outpost of Beryozovo with his children after falling from grace. The scene is set within the cramped, dimly lit interior of a log cabin. Menshikov, a towering figure even in his disgrace, sits brooding, his face a mask of lost power and bitter reflection. His children surround him, each reacting to their plight in their own way: his sick daughter Maria, his younger daughter Alexandra reading the Bible, and his son Alexander staring blankly.

Surikov masterfully uses light and shadow to create a claustrophobic atmosphere, emphasizing the psychological isolation of the fallen statesman. The painting is a poignant meditation on the transience of power and the human cost of political ambition. It resonated deeply with Surikov's own Siberian heritage, capturing the harsh realities of exile that were a recurring theme in Russian history. The work further solidified his reputation for delving into the psychological complexities of historical figures, a trait shared by contemporaries like Nikolai Ge, whose historical and religious paintings often explored intense emotional states.

Boyarynya Morozova

Perhaps Surikov's most iconic and celebrated work, "Boyarynya Morozova," was completed in 1887. This monumental canvas depicts Feodosia Morozova, a 17th-century noblewoman and fervent Old Believer, being dragged away on a sleigh to exile and eventual martyrdom for her refusal to accept the liturgical reforms of Patriarch Nikon. The painting is a symphony of color, movement, and emotion, capturing a pivotal moment in the religious schism (Raskol) that deeply divided Russian society.

Morozova herself is the focal point, her emaciated figure and fanatical, two-fingered gesture of defiance a powerful symbol of unyielding faith. She is surrounded by a vast, diverse crowd, representing all strata of Muscovite society. Some mock her, others look on with pity or fear, while a few, like the yurodivy (holy fool) in the snow, echo her blessing, signifying a hidden sympathy for the Old Believers. Surikov's genius lies in his ability to individualize each figure in the crowd, creating a rich tapestry of human reactions to this dramatic event. The vibrant colors of traditional Russian attire, the crisp winter air, and the dynamic composition contribute to the painting's overwhelming impact. It is considered a pinnacle of Russian historical painting, comparable in its ambition and execution to the grand historical works of European masters, though distinctly Russian in its spirit and subject matter. The influence of artists like Pavel Fedotov, who earlier pioneered critical realism and genre scenes with strong narratives, can be seen as a precursor to the detailed storytelling embraced by Surikov.

Personal Trials and Continued Artistic Endeavors

The 1880s were a period of intense creativity for Surikov, but also one marked by personal tragedy. He had married Elizaveta Avgustovna Share in 1878, a woman of French and Russian descent, with whom he had two daughters, Olga and Elena. Elizaveta was a constant source of support for Surikov, but her health was fragile. She succumbed to a heart condition and died in 1888. Her death was a devastating blow to the artist, leading to a period of profound grief and a temporary cessation of his work.

Seeking solace and a way to reconnect with his roots, Surikov traveled back to Siberia with his daughters. This return to his homeland proved to be artistically rejuvenating. The landscapes, traditions, and people of Siberia provided fresh inspiration.

The Taking of the Snow Town

In 1891, Surikov completed "The Taking of the Snow Town," a work that starkly contrasts with the tragic grandeur of his earlier historical epics. This painting depicts a boisterous and ancient Maslenitsa (Butter Week) folk game popular in Siberia, where participants on horseback attempt to "capture" a fortress made of snow. The canvas explodes with energy, vibrant color, and the joyous abandon of the festival. It is a celebration of Siberian vitality, strength, and communal spirit. Surikov's own Cossack heritage is palpable in the depiction of the skilled horsemen and the raw, untamed energy of the scene. This work demonstrated Surikov's versatility and his deep connection to the folk traditions of his native land. It was well-received and even purchased by Emperor Alexander III, a testament to its appeal.

Yermak's Conquest of Siberia

His Siberian experiences culminated in another historical masterpiece, "Yermak's Conquest of Siberia," completed in 1895. This painting returns to the epic themes of his earlier work, depicting the pivotal 1582 battle between Yermak Timofeyevich's Cossack forces and the Siberian Khanate led by Kuchum Khan. The canvas is a chaotic, swirling mass of combatants, capturing the ferocity and brutality of the clash that opened Siberia to Russian expansion. Surikov drew upon his ancestral connection to Yermak's campaign, infusing the work with a sense of historical authenticity and dramatic intensity. The painting highlights the clash of cultures and the relentless drive of the Cossack pioneers. The dynamic composition and the raw energy of the figures make it a powerful statement on a formative event in Russian history.

Suvorov Crossing the Alps

In 1899, Surikov completed "Suvorov Crossing the Alps," another grand historical canvas celebrating Russian military prowess. The painting depicts the legendary Russian General Alexander Suvorov leading his army through the treacherous Swiss Alps during his Italian and Swiss expedition in 1799. Surikov captures the incredible hardship and determination of the Russian soldiers as they navigate the icy, precipitous mountain passes. Suvorov himself is portrayed as an inspiring leader, sharing the dangers with his men. The painting is a tribute to Russian resilience and courage, and it became one of Surikov's most popular works, resonating with patriotic sentiment. The attention to detail in the soldiers' expressions and the dramatic landscape showcases Surikov's continued mastery of historical narrative.

Artistic Style, Technique, and Influences

Vasily Surikov's artistic style is characterized by a powerful synthesis of academic training, realist observation, and a deeply personal, almost intuitive understanding of Russian history and character. He was a master of complex, multi-figure compositions, often depicting crowd scenes with a remarkable ability to individualize each participant, thereby creating a collective portrait of a historical moment. His figures are not mere historical mannequins but living, breathing individuals caught in the crucible of great events.

His use of color was bold and expressive, often employing rich, resonant hues drawn from Russian folk art, traditional costumes, and the natural landscape. He had a particular gift for capturing the quality of light, whether the cold, clear light of a Moscow winter in "Boyarynya Morozova" or the dim, oppressive atmosphere of Menshikov's exile. His brushwork, while capable of great refinement, could also be vigorous and textured, contributing to the emotional intensity of his scenes.

While deeply rooted in Russian traditions, Surikov was also aware of broader European artistic developments. He traveled to Germany, France, Austria, and Italy in 1883-1884, and later to Switzerland and Spain. He admired the Old Masters, particularly the Venetian colorists like Titian and Paolo Veronese, whose influence can be discerned in the richness and vibrancy of his palette. However, unlike some of his contemporaries who embraced Impressionism or other modern European styles, Surikov remained steadfastly committed to his own form of historical realism, believing it was the most effective means of conveying the drama and significance of Russia's past. His work can be seen as a uniquely Russian counterpoint to the historical painting traditions of Western Europe.

The Abramtsevo Colony, an artistic estate near Moscow owned by the patron Savva Mamontov, also played a role in the cultural milieu Surikov inhabited. While he may not have been a permanent fixture like Viktor Vasnetsov, Apollinary Vasnetsov, Mikhail Nesterov, or Konstantin Korovin, the spirit of national revival and interest in Russian folklore and history fostered at Abramtsevo resonated with Surikov's own artistic preoccupations.

Later Life, Portraits, and Other Works

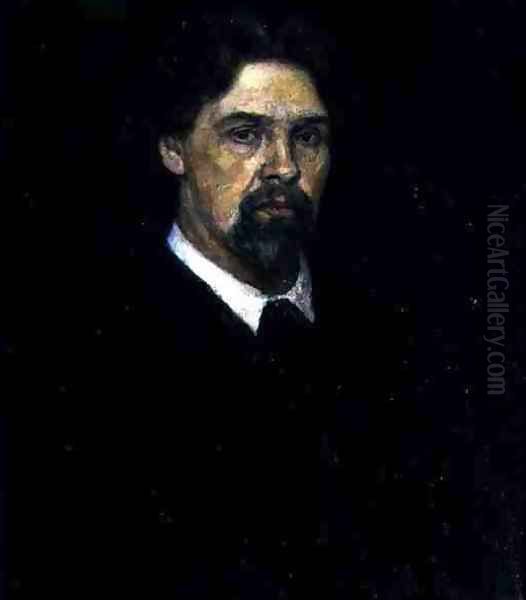

In his later years, Surikov continued to paint, though perhaps not with the same monumental ambition as in his prime. He produced a number of significant portraits, including a striking self-portrait (1913) and portraits of his daughters. These works reveal his keen psychological insight applied to more intimate subjects. He also painted "Stepan Razin" (1906), depicting the 17th-century Cossack rebel leader, a subject that once again allowed him to explore themes of Russian history, rebellion, and the indomitable spirit of the common people. His interest in religious themes also persisted, as seen in works like "The Annunciation" (1914).

His relationship with his son-in-law, Pyotr Konchalovsky, who married his daughter Olga, was an important one in his later life. Konchalovsky, a prominent avant-garde artist and a founding member of the Jack of Diamonds group, represented a very different artistic direction. Despite their stylistic differences, the two artists shared a mutual respect and a deep personal bond. Surikov reportedly admired Konchalovsky's bold use of color, even if it diverged significantly from his own aesthetic. Other artists associated with the Jack of Diamonds included Ilya Mashkov, Aristarkh Lentulov, and Robert Falk, representing a modernist departure from the realism of Surikov's generation.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Vasily Ivanovich Surikov passed away in Moscow on March 19, 1916, due to chronic heart disease. He was buried in the Vagankovo Cemetery, alongside his wife. His death marked the end of an era for Russian historical painting.

Surikov's legacy is immense. His paintings have become iconic representations of Russian history, deeply embedded in the national consciousness. He elevated historical painting beyond mere illustration, transforming it into a vehicle for profound psychological and social commentary. His ability to capture the "soul" of the Russian people in moments of crisis and transformation remains unparalleled. He influenced subsequent generations of Russian artists, and his works continue to be studied and admired for their technical mastery, emotional power, and historical depth.

The Moscow State Academic Art Institute, one of Russia's leading art schools, was named in his honor in 1948, a fitting tribute to a painter who so powerfully shaped the visual narrative of his nation. His major works are prized possessions of Russia's foremost museums, including the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow and the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg, where they continue to inspire awe and reflection in all who behold them. Through his art, Vasily Surikov ensured that the dramatic tapestry of Russia's past would remain vividly alive for generations to come. His contribution extends beyond art; he provided a visual language for understanding the complexities, tragedies, and triumphs of Russian history, making him an enduring cultural hero.