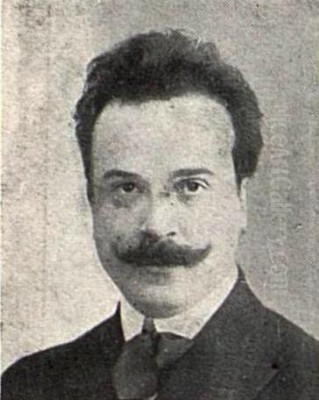

Kimón Loghi stands as a significant, albeit sometimes debated, figure in the landscape of Romanian art history. A painter whose life and career bridged geographical and cultural spheres, Loghi brought a unique sensibility to the burgeoning modern art scene in Romania at the turn of the 20th century. Born in 1873 in Serres, Macedonia (then part of the Ottoman Empire, now Greece), he later established himself in Bucharest, becoming a key proponent of Symbolism in the region. He passed away in Bucharest in 1952, leaving behind a body of work characterized by its rich colour, poetic atmosphere, and exploration of myth and fantasy.

Loghi's art is often described as a confluence of influences, blending the aesthetics of German Symbolism, echoes of Byzantine art, and a personal, often dreamlike, vision. While some critics noted technical imperfections, his work consistently conveyed a strong individual style and deep emotional resonance. He navigated the complex artistic currents of his time, contributing to a pivotal moment when Romanian artists sought to define a modern identity, looking both outward to European trends and inward to national traditions.

Formative Years: From Serres to Munich

Kimón Loghi's artistic journey began far from the Romanian capital where he would eventually make his mark. His origins in Serres, a city with a rich history blending Balkan and Byzantine heritage, may have subtly informed the visual language he later developed. His formal artistic education, however, took place primarily in Bucharest and, crucially, in Munich, a major European art centre at the time, rivaling Paris in certain respects, particularly for Central and Eastern European artists.

In Bucharest, Loghi studied at the School of Fine Arts (Școala de Belle Arte), absorbing the foundational academic training available. A significant influence during his studies, likely in Munich, was the acclaimed Greek painter Nikolaos Gysis, himself a prominent figure of the Munich School, known for his historical and allegorical paintings. This connection highlights the transnational network of artists training in Germany.

Loghi's most decisive educational experience came at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts. There, he studied under Franz von Stuck, a leading figure of German Symbolism and Jugendstil (Art Nouveau). Stuck's own work, often featuring mythological subjects, bold compositions, and a certain dramatic intensity, left an undeniable imprint on Loghi. This tutelage placed Loghi directly within one of the most vibrant currents of European Symbolism, exposing him to its thematic preoccupations and stylistic innovations.

Entering the Romanian Art Scene: Tinerimea Artistică

Loghi made his public debut in the Romanian art world in 1898, exhibiting within the framework of "Tinerimea Artistică" (Artistic Youth). This group was crucial to the development of modern art in Romania. Founded in 1901 by artists seeking alternatives to the entrenched conservatism of the official Salon and academic institutions, Tinerimea Artistică became a vital platform for new ideas and styles. Loghi was among its founding or early prominent members, aligning himself with other progressive artists.

Key figures associated with Tinerimea Artistică included painters like Ștefan Luchian, known for his poignant landscapes and flower studies infused with light and emotion; Arthur Verona, another painter exploring modern idioms; and Ipolit Strâmbu (also cited as Strâmbulescu), who also navigated between tradition and modernity. Together, these artists, including Loghi, sought to synchronize Romanian art with contemporary European movements, particularly Post-Impressionism, Art Nouveau, and Symbolism.

The group's exhibitions provided a space for artists who felt constrained by the academicism promoted by figures associated with the older generation, although masters like Nicolae Grigorescu and Ion Andreescu had already laid the groundwork for modern Romanian painting decades earlier. Tinerimea Artistică represented a conscious effort to break away, embrace individuality, and foster a climate receptive to international trends while still grappling with questions of national artistic identity. Loghi's participation placed him at the heart of this dynamic and often contentious period. His international training, particularly his Munich connections, made him a conduit for Symbolist ideas within this circle.

The Symbolist Vision of Kimón Loghi

Kimón Loghi's art is overwhelmingly defined by Symbolism. This late 19th-century movement prioritized the subjective, the spiritual, and the mysterious over objective reality. Symbolist artists sought to express ideas and emotions indirectly through suggestive forms, colours, and subjects drawn from myth, dreams, literature, and the inner psyche. Loghi fully embraced this ethos, creating works that often feel otherworldly and evocative.

His style is marked by a distinctive use of colour, often rich, vibrant, and employed for emotional and symbolic effect rather than naturalistic description. Critics noted his works' poetic quality and decorative sensibility, sometimes linking the latter to Art Nouveau influences prevalent during his formative years. Fantasy, imagination, and a penchant for narrative, albeit ambiguous, are central to his oeuvre. He demonstrated a concern for composition and symmetry, sometimes lending his works a staged, almost theatrical quality.

The influence of his teacher, Franz von Stuck, is palpable in certain works, particularly in the rendering of figures and the choice of mythological or allegorical themes. Loghi also deeply admired the Swiss Symbolist Arnold Böcklin, famed for atmospheric landscapes and mythological scenes like "Isle of the Dead." Böcklin's influence might be seen in Loghi's creation of mood and his fascination with themes of nature intertwined with myth and mortality. Furthermore, echoes of Byzantine art – perhaps stemming from his cultural background or a conscious aesthetic choice – appear in the stylization of figures, a certain flatness, or decorative patterning in some pieces. This blend resulted in what some have termed a "fantastic realism," a style rooted in recognizable forms but imbued with dreamlike unreality.

Recurring Themes: Mythology, Femininity, and Mortality

Loghi's paintings frequently explore a specific set of themes characteristic of Symbolism but filtered through his personal lens. Mythological subjects, drawn from classical antiquity or folklore, appear regularly. Works like Une vieille romance (1908) suggest an engagement with heroic or legendary narratives, perhaps connecting to his own Greek heritage or the broader Symbolist fascination with ancient myths as repositories of universal truths.

The female figure is a central motif in Loghi's art. He depicted women in various guises – sometimes as ethereal beings, princesses from Byzantine courts (Princesse byzantine, 1908), figures from fairy tales (La Fée du lac, 1907), or enigmatic presences (Girl with Flower in Hair, Oriental). These portrayals often align with Symbolist archetypes of femininity, ranging from the innocent or melancholic muse to the more mysterious, perhaps even subtly dangerous, femme fatale, though Loghi's interpretations tend towards the poetic and dreamlike rather than the overtly decadent. His focus was often on conveying mood and inner states through these figures.

Fairy tales and fantastical scenes provided another rich vein for his imagination. The triptych Monde des contes (World of Fairy Tales, 1911), depicting young women in a forest setting, exemplifies this interest in creating enchanted, self-contained worlds. This aligns with the Symbolist desire to escape the mundane and explore realms of dream and imagination.

A more somber but equally significant theme is death and mortality. The work Post mortem laureatus directly addresses this, likely depicting a female figure associated with death, perhaps allegorically. This preoccupation with mortality, often intertwined with beauty and melancholy, was common among Symbolist artists across Europe, from Gustave Moreau in France to Edvard Munch in Norway, reflecting anxieties and spiritual questionings of the era. Loghi approached the theme with a characteristic poetic sensibility, often tinged with a gentle sadness rather than overt horror.

Signature Works: A Closer Look

Several paintings stand out as representative of Kimón Loghi's artistic contributions and stylistic concerns:

Princesse byzantine (1908): This work exemplifies Loghi's interest in historical fantasy and Byzantine aesthetics. The contemplative female figure, likely rendered with stylized features and perhaps rich, decorative details reminiscent of Byzantine mosaics or icons (even if translated into paint), captures the Symbolist mood of introspection and mystery. The title itself directs the viewer towards a specific imaginative realm.

Monde des contes (1911): This triptych, or series of three large paintings, showcases Loghi's commitment to narrative fantasy. Depicting young women in an enchanted forest, it likely draws on fairy tale motifs to create a world separate from reality, emphasizing imagination, innocence, and perhaps the mysterious forces of nature. Its scale suggests ambition and a desire to make a significant statement within the Symbolist idiom.

La Fée du lac (The Fairy of the Lake, 1907): Similar to Monde des contes, this work delves into the realm of folklore and fantasy. The subject of a water spirit or fairy allows Loghi to explore themes of nature, magic, and the ethereal feminine, common preoccupations in Symbolist art.

Post mortem laureatus: This painting is significant for its direct engagement with the theme of death, intertwined with femininity. The title ("Laureate after death") suggests a complex allegory, perhaps about fame, beauty, and their relationship to mortality. It likely employs Symbolist visual language – ambiguous setting, evocative pose, symbolic objects – to convey its melancholic message.

Girl with Flower in Hair and Oriental: These works highlight Loghi's skill in portraying enigmatic female figures. They often feature subtle plays of light and shadow, rich colour harmonies or contrasts, and a focus on capturing a psychological state or mood rather than a simple likeness. The title Oriental suggests an engagement with Orientalist themes, common in 19th-century European art, but likely filtered through Loghi's decorative and Symbolist lens.

Le Ballade (exhibited 1903): Shown at an early Tinerimea Artistică exhibition, this work likely represented his blend of Romantic sensibility with Symbolist aesthetics, possibly depicting a scene inspired by medieval ballads or legends, showcasing his narrative and imaginative inclinations early in his public career.

Entre les fleurs (Among the Flowers, 1898): As one of his earliest exhibited works, this piece is noted as showing the influence of his teacher, Franz von Stuck, likely in its composition, theme, or handling of the figure.

These works collectively demonstrate Loghi's consistent engagement with Symbolist themes, his distinctive colour sense, his blending of influences, and his contribution to the imaginative and decorative currents within Romanian modern art.

Munich's Legacy and Romanian Reception

The time Kimón Loghi spent in Munich under Franz von Stuck was undeniably formative and profoundly shaped his artistic direction. Stuck himself reportedly recognized Loghi's talent. The sophisticated, often dramatic, and psychologically charged Symbolism prevalent in Munich provided Loghi with a powerful set of tools and thematic interests that he brought back to Romania. This connection to a major European art centre lent Loghi a certain prestige but also became a point of contention.

While Loghi was integrated into the Romanian art scene, particularly through Tinerimea Artistică, and was even recommended to the Romanian public by figures like Dimitrie Karabăt (as mentioned in sources), his art sometimes met with mixed reactions. Some Romanian critics, invested in defining a distinct national artistic identity, felt Loghi's style was too indebted to foreign models, particularly German Symbolism. They perceived a lack of deep connection to the "Romanian soul" or the specificities of Romanian landscape and life, which artists like Luchian or, later, figures such as Nicolae Tonitza and Gheorghe Petrașcu, were seen to capture more authentically, albeit in different styles.

His emphasis on fantasy, decoration, and mythology was occasionally criticized as being overly literary or detached from reality. The very qualities that defined his Symbolist approach – the dreamlike atmosphere, the rich and sometimes non-naturalistic colour, the imaginative subjects – could be seen by some as lacking the perceived robustness or groundedness associated with emerging Romanian traditions influenced by Grigorescu or Andreescu. His cross-cultural background – Macedonian origin, German training, Romanian career – further complicated his positioning. He was an artist operating at a cultural crossroads.

However, his commitment to imagination and individual expression resonated with others. For instance, his interests aligned with those of the influential Romanian architect Ion Mincu, a key figure in the Neo-Romanian architectural style, who also valued artistic personality and imaginative richness. Loghi's participation in international events, like the 1900 Paris Exposition Universelle where he represented Romania, indicates he was seen, at least by some official bodies, as a significant contemporary artist.

Art Historical Significance and Re-evaluation

In Romanian art history, Kimón Loghi occupies the position of a key Symbolist painter active during a crucial period of transition and modernization. He was instrumental in introducing and popularizing Symbolist aesthetics and themes within the Romanian context, contributing significantly to the diversity of artistic expression fostered by the Tinerimea Artistică movement. His work stands as a testament to the international connections of Romanian artists at the time and their engagement with broader European trends.

While contemporary criticism was sometimes divided, and his reputation may have fluctuated over the decades, recent art historical scholarship tends to re-evaluate his contribution more favourably. He is recognized as a pioneer of Symbolism in Romania, an artist who, despite criticisms of foreign influence, developed a personal and recognizable style characterized by its poetic intensity and visual richness. His exploration of myth, dream, and the psyche aligns him firmly with the core concerns of the international Symbolist movement, whose key figures included Gustav Klimt in Vienna and Puvis de Chavannes in France.

His unique blend of influences – the rigorous training of the Munich Academy under Stuck, the lingering echoes of Byzantine art, and the specific cultural milieu of Bucharest – resulted in a hybrid style that enriches the narrative of Romanian modern art. He demonstrated that Romanian artists could engage deeply with international movements while forging individual paths. The debates surrounding his work also reflect broader anxieties within Romanian culture at the time about national identity, tradition, and modernity.

Unlike some artists whose lives are marked by dramatic events or public scandals, Loghi's known history appears relatively focused on his artistic production and participation in the art world. No major controversies or hidden anecdotes are prominently featured in standard accounts of his life. His legacy rests on his paintings – works that invite viewers into evocative, dreamlike worlds, rendered with a distinctive sensitivity to colour and mood.

Conclusion: A Poetic Vision

Kimón Loghi remains an important figure for understanding the complexities of Romanian art at the turn of the 20th century. As a painter of Macedonian origin educated in Munich and active in Bucharest, he embodied the cultural exchanges shaping the region. His commitment to Symbolism brought a vital current of European modernism into Romanian art, enriching it with themes of myth, fantasy, and introspection.

Though sometimes criticized for perceived foreignness or excessive decorativeness, his work possesses a unique poetic charm and visual appeal. His paintings, from Byzantine princesses to fairy-tale landscapes and enigmatic portraits, consistently explore the realms of imagination and emotion. Through his involvement with Tinerimea Artistică and his distinctive body of work, Kimón Loghi carved out a unique place in Romanian art history, leaving behind a legacy that continues to intrigue and invite re-interpretation as a bridge between different cultural worlds and artistic sensibilities.