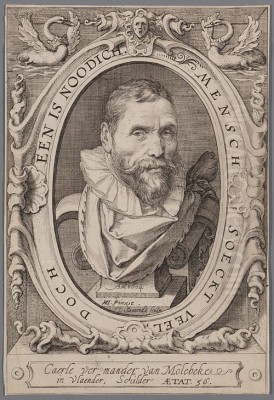

Karel van Mander the Elder stands as a pivotal figure in the art history of the Low Countries, a multifaceted talent who excelled as a painter, poet, art theorist, and biographer. Born in Meulebeke, in the County of Flanders, in May 1548, and passing away in Amsterdam on September 2, 1606, his life and work bridged the late Renaissance and the dawn of the Dutch Golden Age. His contributions, particularly his seminal biographical work Het Schilder-boeck (The Book of Painters), have earned him the enduring moniker "the Vasari of the North," drawing a direct parallel to the Italian Renaissance chronicler Giorgio Vasari. Van Mander's influence extended beyond his writings; his artistic practice and his role in fostering a new generation of artists were instrumental in shaping the trajectory of Northern European art.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born into a noble family in Flanders, Karel van Mander received an education befitting his station, which likely included classical literature and languages, laying a foundation for his later scholarly pursuits. His artistic inclinations emerged early, leading him to apprenticeships under notable Flemish masters. He first studied with the poet-painter Lucas de Heere in Ghent. De Heere, himself a versatile figure, would have exposed Van Mander to a humanist approach to art, one that valued intellectual content and classical learning alongside technical skill.

Following his time with De Heere, Van Mander continued his training under Pieter Vlerick in Kortrijk and Tournai between 1568 and 1569. Vlerick was known for his history paintings and landscapes, and this period would have further honed Van Mander's skills in composition and narrative depiction. These formative years in Flanders immersed him in the rich artistic traditions of the region, which, while distinct, were increasingly engaging with the stylistic innovations emanating from Italy.

The Italian Sojourn: A Crucible of Influence

Like many ambitious Northern European artists of his era, Van Mander recognized the necessity of an Italian journey to complete his artistic education. Around 1573, he embarked on this transformative pilgrimage, making his way to Rome, the epicenter of the art world. He resided in the Eternal City from approximately 1573 to 1577, a period that proved profoundly influential. Italy, and Rome in particular, was a living museum, offering direct exposure to the masterpieces of antiquity and the High Renaissance, including the works of giants like Michelangelo, Raphael, and Titian.

During his Roman sojourn, Van Mander was not merely a passive observer. He actively engaged with the contemporary art scene and formed crucial relationships. One of the most significant was his friendship with the Flemish painter Bartolomeus Spranger, a leading proponent of Mannerism who was then working for Cardinal Alessandro Farnese and later became court painter to Emperor Rudolf II in Prague. Spranger's sophisticated, elegant, and often erotically charged style left a discernible mark on Van Mander's own artistic development.

Van Mander also found patronage in Italy. He was commissioned by the Italian nobleman Michelangelo Spada to execute frescoes in the Palazzo Spada in Terni, a project that allowed him to work on a grand scale and engage with mythological and allegorical themes popular at the time. He also received commissions from several cardinals for religious genre scenes, demonstrating his versatility. It was during this period that he reportedly mastered the art of capricci, imaginative and whimsical compositions, and is even credited by some with discovering ancient Roman catacombs, or "caves," further underscoring his antiquarian interests. His experiences in Italy, observing, learning, and practicing, were meticulously absorbed and would later inform both his paintings and his writings.

Return to the Netherlands: Haarlem and the Academy

The religious and political turmoil of the period, particularly the Eighty Years' War, likely influenced Van Mander's decision to leave Italy. After a brief stay in Vienna, where he may have collaborated with Spranger and Hans Mont on designs for a triumphal arch for Emperor Rudolf II, he returned to the Low Countries. He initially settled in Meulebeke but, due to the ongoing religious strife (Van Mander was a Mennonite, a pacifist Anabaptist sect), he eventually sought refuge in the Northern Netherlands.

In 1583, Karel van Mander established himself in Haarlem, a city rapidly becoming a vibrant artistic center. Here, his Italian experiences and Mannerist inclinations found fertile ground. He became a central figure in a circle of artists eager to absorb and adapt Italianate styles. Alongside the brilliant engraver and painter Hendrick Goltzius and the painter Cornelis Corneliszoon van Haarlem, Van Mander is traditionally credited with co-founding what is often referred to as the "Haarlem Academy" or "Haarlem Mannerists."

While perhaps not a formal institution in the modern sense, this informal gathering or workshop served as a hub for artistic exchange and instruction. The artists shared drawings, studied from live models (a practice Van Mander advocated for), and discussed art theory, particularly the principles of Italian Renaissance and Mannerist art. They aimed to elevate the status of painting in the North by imbuing it with the intellectual rigor and sophisticated aesthetics they admired in Italian art. Van Mander's role as a teacher and mentor during this period was crucial, influencing a generation of artists who would contribute to the burgeoning Dutch Golden Age. His own paintings from this time often feature elongated figures, complex poses, and mythological or allegorical subjects characteristic of international Mannerism.

The Magnum Opus: Het Schilder-boeck

While Van Mander was a respected painter, his most enduring legacy lies in his monumental literary achievement, Het Schilder-boeck (The Book of Painters), published in Haarlem in 1604. This comprehensive work was a landmark in art historiography and theory in Northern Europe, earning him comparisons to Giorgio Vasari, whose Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1550, revised 1568) had set the standard for artist biographies.

Het Schilder-boeck is a multi-part volume. It begins with "Den Grondt der Edel Vry Schilder-const" (The Foundations of the Noble and Free Art of Painting), a didactic poem in fifteen chapters offering practical and theoretical advice to young painters. This section covers topics such as drawing, composition, human anatomy, proportion, expression of emotions, color, light and shadow, landscape painting, and the depiction of animals. It reflects Van Mander's own artistic ideals, emphasizing the importance of inventio (invention), disegno (drawing/design), and maniera (style).

The subsequent sections contain the biographies that form the core of the book's fame:

1. Lives of the famous ancient painters (Egyptian, Greek, and Roman), drawing heavily on classical sources like Pliny the Elder.

2. Lives of the famous modern Italian painters, from Cimabue to his contemporaries, effectively translating and adapting Vasari's work for a Dutch audience, but also adding new information. Artists like Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, Michelangelo, Titian, and Correggio are featured.

3. Lives of the famous Netherlandish and German painters, which is arguably the most original and valuable part of the book. This section provides indispensable information on artists from Jan van Eyck and Rogier van der Weyden through Albrecht Dürer, Hans Holbein the Younger, Lucas van Leyden, and Pieter Bruegel the Elder, up to Van Mander's own contemporaries like Hendrick Goltzius and Abraham Bloemaert. For many of these Northern artists, Van Mander's accounts are the primary, and sometimes only, contemporary source of biographical information.

4. An appendix on Ovid's Metamorphoses, providing iconographical guidance for painters tackling mythological subjects.

Het Schilder-boeck was more than just a collection of biographies; it was an attempt to create a canon of Northern art, to provide a theoretical underpinning for artistic practice, and to elevate the social and intellectual status of the artist. It became an essential reference for artists and connoisseurs for centuries and remains a vital resource for art historians today, despite some inaccuracies and biases inherent in such a work.

Artistic Style and Oeuvre

Karel van Mander's own paintings reflect the artistic currents of his time, particularly the international Mannerist style that he helped popularize in the Northern Netherlands. His subjects were often drawn from biblical narratives, mythology, and allegory, aligning with the hierarchy of genres that placed history painting at the apex.

His style is characterized by elongated figures, often in contorted or elegant S-curve poses, a hallmark of Mannerism. Compositions tend to be crowded and dynamic, with a focus on narrative clarity and dramatic effect. He paid considerable attention to anatomical detail, though sometimes stylized for expressive purposes. His color palettes could be rich and varied, and he demonstrated skill in rendering textures and drapery.

Among his representative works, several stand out:

The Dance of Salome: This painting exemplifies his Mannerist tendencies with its dynamic composition, elongated figures, and dramatic subject matter. The swirling movement and expressive gestures create a sense of theatricality.

Christ in the Wine Press: A theological allegory, this work showcases Van Mander's ability to translate complex religious concepts into visual form, often employing rich symbolism and, in some versions, intricate gold detailing.

Peasant Fair (1592): While known for more elevated subjects, Van Mander, like many Netherlandish artists, also depicted scenes of everyday life. This work, likely influenced by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, shows his engagement with genre themes, though often imbued with a moralizing undertone.

Annunciation (1593): A religious scene treated with the elegance and sophisticated composition typical of his style.

Dronken soldaat vergezeld door... (Drunken Soldier Accompanied by...): This title suggests a genre or allegorical scene, possibly with a moral message, a common theme in Netherlandish art.

Studie van een hoofd (Study of a Head, 1592): Such studies demonstrate his commitment to observation and the practice of drawing, which he emphasized in Het Schilder-boeck.

Van Mander also produced designs for tapestries and stained glass, further showcasing his versatility. While his painted oeuvre is perhaps overshadowed by his literary contributions and the work of some of his more famous contemporaries like Goltzius, his paintings are important examples of Dutch Mannerism and provide a visual counterpart to the artistic theories he espoused. He was a competent and knowledgeable painter who played a significant role in transmitting Italianate ideas to the North.

Later Years and Legacy

In his later years, around 1603, shortly before the publication of Het Schilder-boeck, Karel van Mander moved from Haarlem to Amsterdam, the rapidly ascending commercial and cultural hub of the Dutch Republic. He continued to paint and write in Amsterdam until his death on September 2, 1606, at the age of 58. He was buried in the Oude Kerk (Old Church) in Amsterdam.

Van Mander's legacy is multifaceted. As a painter, he was a key figure in the Haarlem Mannerist school, contributing to a style that was sophisticated, intellectual, and international in outlook. His pupils, including his son Karel van Mander II (who became a successful tapestry designer and painter at the Danish court), and indirectly figures like Frans Hals (who emerged from the Haarlem artistic environment Van Mander helped shape), carried forward aspects of his influence.

However, it is as an art theorist and historian that his impact is most profound and lasting. Het Schilder-boeck was a foundational text for Dutch art theory and historiography. It provided a framework for understanding the history of art, particularly Northern art, and offered invaluable guidance to generations of artists. It preserved biographical details and anecdotes about numerous artists that would otherwise have been lost, including the famous (though perhaps apocryphal) story of Pieter Bruegel the Elder "swallowing the Alps and spitting them out onto his canvases."

The book's influence extended beyond the Netherlands. It was translated and read across Europe, contributing to the broader understanding and appreciation of Netherlandish and German art. For art historians, it remains an indispensable, if critically approached, primary source.

Van Mander's Circle: Contemporaries and Influences

Karel van Mander's life and work were deeply intertwined with a wide network of artists, both predecessors he admired and contemporaries with whom he collaborated or competed. His writings reveal his awareness of a broad artistic landscape.

His early masters, Lucas de Heere and Pieter Vlerick, provided his initial training in the Flemish tradition. His Italian stay brought him into contact with Bartolomeus Spranger, whose sophisticated Mannerism was a key influence. He would have studied the works of Italian masters like Michelangelo, Raphael, Titian, and Correggio, and he explicitly acknowledged his debt to Giorgio Vasari as a model for his biographical project.

In Haarlem, his closest associates were Hendrick Goltzius and Cornelis Corneliszoon van Haarlem. Goltzius, a virtuoso engraver and later a painter, was a leading figure of Dutch Mannerism, and their collaboration in the "Haarlem Academy" was crucial. Cornelis van Haarlem, known for his large-scale history paintings with muscular nudes, was another pillar of this group.

Through Het Schilder-boeck, Van Mander engaged with the legacy of earlier Northern masters. He wrote extensively on Jan van Eyck, Rogier van der Weyden, Albrecht Dürer, Lucas van Leyden, and, with particular insight, Pieter Bruegel the Elder. His admiration for Bruegel is evident, and he helped shape the latter's posthumous reputation. He also documented many lesser-known artists, providing a rich tapestry of the artistic life of the Low Countries.

Other contemporaries mentioned or influenced by him include Abraham Bloemaert of Utrecht, another important Mannerist painter, and Joachim Wtewael. The generation that followed, including early Dutch Golden Age masters like Frans Hals in Haarlem, built upon the foundations laid by Van Mander and his circle, even as they moved towards greater naturalism. His son, Karel van Mander II, carried his name and artistic lineage to the Danish court.

Historical Evaluation and Enduring Significance

Karel van Mander the Elder is rightly celebrated as a cornerstone of Northern European art history. While some critics have occasionally found his own artistic output less groundbreaking than that of some of his peers, his overall contribution is undeniable. He was a man of broad learning, a skilled artist, and a dedicated chronicler and theorist of art.

His role in disseminating Italian artistic ideas and fostering the Mannerist style in the Netherlands was vital for the development of Dutch art. The Haarlem Academy, however informal, became a crucible for these new ideas, nurturing a generation of artists who would soon forge the distinctive character of the Dutch Golden Age.

Het Schilder-boeck remains his most significant achievement. It not only preserved invaluable information but also helped to define a distinct Northern European artistic identity. It provided a theoretical basis for art education and appreciation at a time when the Netherlands was emerging as a major cultural power. By documenting the lives and works of artists, Van Mander elevated their status and asserted the intellectual dignity of their profession.

In conclusion, Karel van Mander the Elder was more than just "the Vasari of the North." He was an active participant in the artistic transformations of his era, a teacher, a painter, and a scholar whose work provided a vital bridge between the Renaissance and the Baroque, between Italy and the North, and between artistic practice and art theory. His legacy continues to inform our understanding of one of the richest periods in European art history.