Cornelis Cornelisz. van Haarlem stands as a pivotal figure in the art history of the Netherlands, a leading proponent of Northern Mannerism and a significant contributor to the Dutch Golden Age. Born in the vibrant city of Haarlem in 1562, his life and career spanned a period of immense political, social, and artistic transformation. He was not merely a painter but an innovator, an educator, and a central personality within the Haarlem artistic community. His works, characterized by dynamic compositions, dramatic themes, and a distinctive approach to the human form, left an indelible mark on his contemporaries and subsequent generations. This exploration delves into the life, artistic evolution, key works, and lasting influence of this remarkable Dutch Master.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Cornelis Cornelisz. was born into a prosperous family in Haarlem. His early life coincided with the turbulent period of the Eighty Years' War, the Dutch revolt against Spanish rule. A dramatic anecdote from his childhood illustrates the era's dangers: during the brutal Spanish siege of Haarlem in 1572-73, his parents fled the city, leaving the young Cornelis and his brother Pieter behind in the care of others. This early exposure to conflict and upheaval may have subtly informed the dramatic intensity found in many of his later works.

Despite the surrounding turmoil, Haarlem was a burgeoning center for the arts, and Cornelis received a solid artistic education. His initial training was under the painter Pieter Pietersz. the Elder, likely beginning in Haarlem before Pietersz. moved to Amsterdam around 1569. This foundational training would have grounded him in the prevailing Netherlandish traditions of the time.

Seeking broader horizons and more advanced instruction, the young artist embarked on travels around 1579 or 1580. He journeyed to Rouen in France for a period, though details of his stay are scarce. More significantly, he spent time in Antwerp, then a major artistic hub in the Southern Netherlands, despite its recent political and economic troubles following the Spanish Fury. In Antwerp, he studied for about a year with the respected painter Gillis Coignet, a versatile artist known for his landscapes, portraits, and mythological scenes, often imbued with Mannerist tendencies. This exposure to the more sophisticated and internationally-influenced Antwerp scene was crucial for his development.

The Haarlem Academy and the Rise of Mannerism

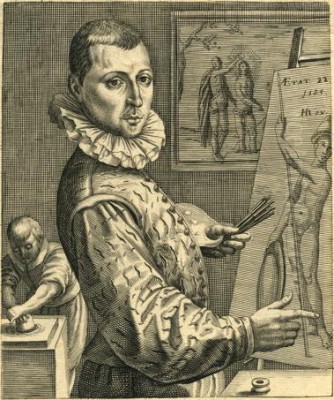

Upon returning to his native Haarlem around 1581 or 1583, Cornelis Cornelisz. found a city eager to reclaim its cultural prominence. He quickly connected with two other ambitious and influential figures: the renowned engraver and later painter Hendrick Goltzius, and the painter, poet, and art theorist Karel van Mander. Van Mander, a Flemish refugee who had travelled extensively in Italy, brought firsthand knowledge of Italian Renaissance and Mannerist art, along with theoretical ideas about artistic practice.

Together, these three artists are traditionally credited with founding the so-called "Haarlem Academy" around the mid-1580s. While perhaps not a formal institution in the modern sense, it represented a collaborative effort to study the human form, particularly the male nude, from life models. This practice, relatively novel in the Northern Netherlands at the time, was central to the development of the distinctive Haarlem Mannerist style. They sought to emulate the Italian masters' command of anatomy and complex poses, drawing inspiration from prints and drawings circulating from Italy, particularly those after artists like Michelangelo and Raphael, but also contemporary Mannerists.

A key influence, disseminated largely through prints brought back by Van Mander and Goltzius (who travelled to Italy in 1590-91), was the work of Bartholomäus Spranger. Spranger, a Flemish painter active at the Imperial court in Prague, epitomized late international Mannerism with his elegant, elongated figures, complex allegories, erotic undertones, and sophisticated, artificial poses. His style resonated deeply with the Haarlem artists, providing a model for depicting mythological and biblical narratives with unprecedented dynamism and anatomical bravura.

Cornelis Cornelisz. rapidly absorbed these influences, becoming a leading painter within this new movement. His early works from the late 1580s and 1590s are prime examples of Haarlem Mannerism. They are often large-scale history paintings, featuring crowded compositions packed with muscular, often nude figures depicted in contorted, difficult poses (known as figura serpentinata). The anatomy, while studied, is frequently exaggerated for dramatic effect, characterized by bulging muscles and powerful physiques – a feature sometimes dubbed the "bulbous style."

Masterpieces of Haarlem Mannerism

Several key works exemplify Cornelis van Haarlem's mastery of the Mannerist style during its peak in Haarlem. The Fall of the Titans (also known as The Titanomachy), painted in 1588 and now housed in the Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen, is a quintessential example. This dramatic mythological scene depicts the Olympian gods overthrowing the Titans in a chaotic whirlwind of muscular bodies tumbling through space. The composition is deliberately complex and energetic, filled with foreshortened limbs and strained poses, showcasing the artist's ambition to rival Italian masters in depicting epic conflict and the nude figure in motion.

Another powerful work from this period is The Massacre of the Innocents, dated 1590 (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam). Commissioned by the city of Haarlem, this large canvas translates the biblical horror into a maelstrom of violence and despair. Again, the focus is on the human body under duress – nude infants, struggling mothers, and brutal soldiers fill the canvas in a complex, almost overwhelming arrangement. The heightened drama, emotional intensity, and emphasis on anatomical display are hallmarks of Haarlem Mannerism. The painting served not only as a display of artistic skill but perhaps also resonated with a populace that had experienced the brutalities of war firsthand.

The Wedding of Peleus and Thetis, completed in 1593 (Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem), offers a slightly different facet of his Mannerist output. While still featuring a multitude of figures, many nude or semi-nude, in elegant and varied poses, the overall mood is one of mythological celebration rather than violent conflict. It depicts the feast disrupted by Eris, the goddess of discord, who throws the golden apple, sparking the judgment of Paris and ultimately leading to the Trojan War. The intricate composition and the sophisticated depiction of classical mythology catered to the learned tastes of Haarlem's elite patrons. The painting showcases Cornelis's ability to handle complex narratives and orchestrate large groups of figures with decorative flair.

These works, along with others like Hercules and Achelous (c. 1590), demonstrate Cornelis van Haarlem's technical virtuosity and his full embrace of Mannerist principles: intellectual subject matter, complex and artificial compositions, elongated or exaggerated anatomy, and a focus on the nude figure as the primary vehicle for expression. His skill in rendering musculature and dynamic poses was widely admired and emulated.

Stylistic Evolution: Towards Dutch Realism

While Cornelis Cornelisz. van Haarlem is most famous for his Mannerist works, his style was not static. From the mid-1590s onwards, a gradual shift can be observed in his paintings. While he continued to paint mythological and biblical subjects, the extreme contortions and anatomical exaggerations began to soften. His compositions became somewhat clearer, and his figures, while still robust, often adopted more naturalistic poses and proportions.

This evolution reflected a broader trend in Dutch art, moving away from the international Mannerist style towards a greater degree of realism and naturalism, which would become the hallmark of the Dutch Golden Age. Factors contributing to this shift likely included changing tastes among patrons, a renewed interest in native traditions, and perhaps the artist's own maturation.

The Fall of Man (1592, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam) stands as an interesting work from this transitional period. While Adam and Eve are depicted with the powerful musculature characteristic of his Mannerist phase, their poses are somewhat less convoluted than in works like The Fall of the Titans. The landscape setting also begins to play a more significant role. The painting retains a strong dramatic impact but hints at the move towards greater clarity.

Later works, such as Adam and Eve dated 1622 (Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem), show a more pronounced shift. The figures are still idealized but possess a greater softness and more naturalistic interaction compared to his earlier, more stylized nudes. The influence of Italian Renaissance ideals, perhaps filtered through later interpretations, seems more apparent than the high-strung energy of Spranger-inspired Mannerism.

Similarly, Bathsheba at her Bath (1594, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam) presents a sensual biblical scene. While Bathsheba's pose has Mannerist elegance, the overall treatment feels somewhat calmer and more focused on texture and light compared to the tumultuous energy of his earlier history paintings. The attention to detail in the setting and accessories points towards the growing Dutch interest in realistic depiction.

Portraiture and Civic Life

Alongside his history paintings, Cornelis Cornelisz. van Haarlem was also an accomplished portraitist, contributing significantly to a genre that flourished in the Dutch Republic. His most famous works in this field are the group portraits of the Haarlem civic guards (schutterij). These militia companies played an important social and ceremonial role in Dutch cities, and commissioning large group portraits to hang in their guild halls became a tradition.

His earliest known major work is, in fact, a group portrait: the Banquet of the Officers of the St George Militia Company dated 1583 (Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem). Created shortly after his return to the city, it already demonstrates his skill in capturing individual likenesses and arranging a complex group composition. While perhaps less dynamic than later examples by artists like Frans Hals, it established Cornelis as a capable portrait painter early in his career.

He painted several other militia company portraits, including another banquet scene for the St George guard in 1599. These commissions required not only artistic skill but also diplomatic tact, ensuring each member felt adequately represented and recognized. Cornelis managed these challenges successfully, creating lively and engaging depictions of Haarlem's prominent citizens. His approach to group portraiture, while perhaps more orderly than the revolutionary dynamism Frans Hals would later introduce, laid important groundwork for the genre's development in Haarlem. He also painted individual portraits throughout his career, often depicting fellow artists or members of Haarlem's elite.

Workshop, Influence, and Legacy

As a leading artist in Haarlem for several decades, Cornelis Cornelisz. van Haarlem undoubtedly maintained an active workshop. While documentation is not extensive, several artists are recorded as having studied with him or been significantly influenced by his style. Gerrit Pietersz. Sweelink, known for his biblical scenes, is considered one of his pupils. Other Haarlem artists like Cornelis Engelsz. and Cornelis Jacobsz. Delff also show stylistic affinities, suggesting his impact on the local art scene was considerable.

His influence extended beyond his direct pupils. His compositions, particularly the Mannerist history paintings, were widely disseminated through prints. Engravers associated with Hendrick Goltzius, including Goltzius himself before he focused more on painting, as well as Jacob Matham (Goltzius's stepson) and Jan Muller, created numerous engravings after Cornelis's designs. These prints circulated throughout the Netherlands and Europe, spreading the Haarlem Mannerist style and enhancing Cornelis's reputation far beyond his native city.

Perhaps his most significant influence was on the next generation of Haarlem painters, most notably Frans Hals. Although Hals developed a radically different, much looser painting technique, his early works show an awareness of Cornelis's dynamic compositions and figure types. Cornelis's role in establishing Haarlem as a major artistic center certainly helped pave the way for Hals's later success.

Interestingly, the influence of Haarlem Mannerism, partly through Cornelis's work and its dissemination via prints, reached unexpected corners of the world. Art historians have noted stylistic connections between Dutch Mannerist prints and paintings produced in the Deccan sultanate of Bijapur in India during the early 17th century, suggesting a global reach for these artistic ideas.

Cornelis's contemporary, Abraham Bloemaert in Utrecht, worked in a related Mannerist style, and the two artists likely knew each other's work. Joachim Wtewael, also active in Utrecht, was another key proponent of Northern Mannerism, sharing with Cornelis an interest in complex compositions and mythological themes rendered with refined detail.

Personal Life and Final Years

Details about Cornelis Cornelisz. van Haarlem's personal life remain somewhat fragmented. In 1603, he married Maritgen Arentsdr. Deyman, the daughter of a former mayor of Haarlem. This marriage connected him to the city's patrician class. However, sources suggest the marriage may not have been entirely happy, and it reportedly ended in divorce or separation later in life. They had children, but some accounts mention the early death of offspring, adding a layer of personal tragedy to his successful career.

His son, Cornelis Bega (born Cornelis Pietersz. Begijn, he later adopted the surname Bega), also became a notable painter and etcher, though his style focused primarily on genre scenes of peasant life, diverging significantly from his father's grand historical and mythological subjects. Bega is often considered more a follower or part of the broader Haarlem school than a direct stylistic inheritor of his father's Mannerism.

Cornelis Cornelisz. remained an esteemed figure in Haarlem throughout his long life. He held positions within the Guild of St Luke (the painters' guild) and continued to receive important commissions. He died in Haarlem on November 11, 1638, at the age of 76, leaving behind a substantial body of work and a significant artistic legacy. His daughter reportedly inherited many of his assets.

Conclusion: A Defining Figure of an Era

Cornelis Cornelisz. van Haarlem was more than just a skilled painter; he was a central force in shaping the artistic landscape of the late 16th and early 17th centuries in the Northern Netherlands. As a co-founder of the Haarlem Academy and a leading exponent of Northern Mannerism, he brought a new level of sophistication, dynamism, and anatomical understanding to Dutch art, heavily influenced by international trends yet forging a distinct local character. His dramatic history paintings, filled with powerful figures and complex narratives, set a high standard for ambition and technical skill.

While his style evolved over his long career, moving from the height of Mannerist invention towards the more naturalistic tendencies of the Dutch Golden Age, his impact remained profound. Through his own works, his role as a teacher, and the widespread circulation of prints after his designs, he influenced contemporaries like Abraham Bloemaert and the subsequent generation, including the great Frans Hals. His contributions to both history painting and portraiture cemented his status as one of Haarlem's most important masters, a vital link between late Renaissance internationalism and the burgeoning national style of the Dutch Republic. His legacy endures in the powerful and often breathtaking canvases that showcase the energy and innovation of a transformative period in art history.