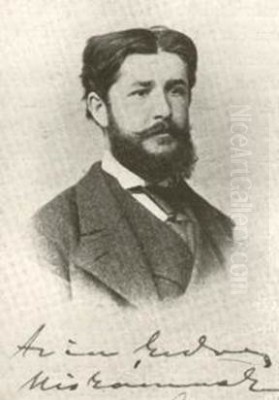

László Paál (1846–179) stands as a significant, albeit tragically short-lived, figure in 19th-century Hungarian and European art. A landscape painter of profound sensitivity, Paál is celebrated for his atmospheric and emotionally resonant depictions of nature, deeply rooted in the traditions of French Realism and the Barbizon School, yet infused with his unique lyrical vision and an early adoption of impressionistic techniques. His canvases, often imbued with a melancholic beauty, capture the fleeting moods of the forest, the subtle play of light, and the quiet dignity of the rural world, securing his place as one of Hungary's foremost landscape artists.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Zám, Transylvania (then part of the Austrian Empire, now Zam, Romania), László Paál's early life was marked by a burgeoning interest in the natural world that would later define his artistic oeuvre. His family's circumstances eventually led him to Budapest, a city awakening to its own cultural and artistic identity. It was here that Paál began to formalize his artistic inclinations before seeking more advanced training.

His quest for artistic knowledge took him to the prestigious Vienna Academy of Fine Arts in 1866. During this period, the Academy was a crucible of diverse artistic currents, though still largely dominated by academic traditions. In Vienna, Paál would have been exposed to various influences, including the lingering Romanticism and the emerging Realist trends that were challenging established norms across Europe. It is likely he studied under figures such as the Austrian landscape painter Albert Zimmermann, known for his heroic and atmospheric landscapes, which could have provided an early academic grounding in the genre. The rigorous training in Vienna would have honed his technical skills in drawing and composition, providing a solid foundation for his later, more expressive, explorations of landscape.

The Allure of Barbizon and Realism

The mid-19th century was a period of profound artistic transformation. The Romantic emphasis on emotion and the sublime was giving way to Realism, a movement that sought to depict the world and its inhabitants with unvarnished truth. A pivotal manifestation of this shift in landscape painting was the Barbizon School in France. Centered around the village of Barbizon near the Forest of Fontainebleau, artists like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Jean-François Millet, Théodore Rousseau, and Charles-François Daubigny rejected idealized, classical landscapes in favor of direct observation of nature, often painting en plein air (outdoors) to capture the immediate effects of light and atmosphere.

Paál was deeply drawn to this artistic philosophy. The works of Millet, with their dignified portrayal of peasant life and rural labor, resonated with a desire for authenticity. Gustave Courbet, the arch-Realist, with his bold, unidealized depictions of everyday scenes and landscapes, also exerted a considerable influence on Paál and his contemporaries. Corot’s lyrical, silvery landscapes, which masterfully balanced observation with poetic sensibility, particularly captivated Paál. These artists, along with others like Narcisse Virgilio Díaz de la Peña, known for his dramatic forest interiors, and Constant Troyon, famed for his animal paintings within realistic landscapes, shaped Paál's artistic direction. He absorbed their commitment to truthfulness, their focus on the humble aspects of nature, and their innovative approaches to light and color.

Paris, Munkácsy, and the Forest of Fontainebleau

In 1870, Paál made the crucial decision to move to Paris, the undisputed art capital of the world. This move was pivotal, not only for his exposure to the vibrant art scene but also for cementing his lifelong friendship and artistic camaraderie with the already renowned Hungarian painter Mihály Munkácsy. Munkácsy, older and more established, became a mentor and a close companion. Their shared Hungarian roots and artistic aspirations forged a strong bond.

Together, they often worked in and around Barbizon, immersing themselves in the Forest of Fontainebleau. This ancient woodland, with its majestic oaks, rugged rock formations, and dappled light, became Paál’s principal muse. He was not merely a visitor but became an integral part of the later phase of the Barbizon movement. He lived in Barbizon for extended periods, absorbing its spirit and translating its myriad moods onto canvas. His association with Munkácsy was artistically fruitful; they reportedly collaborated on a book on painting techniques, and Munkácsy's own powerful realism and dramatic use of chiaroscuro likely influenced Paál, though Paál’s focus remained more intimately tied to pure landscape.

The Parisian art world was then buzzing with the nascent Impressionist movement, led by artists like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Alfred Sisley. While Paál never fully embraced Impressionism's broken brushwork or scientific color theory, his later works show a heightened sensitivity to transient light effects and a brighter palette, suggesting an awareness and absorption of these contemporary developments. He was, in essence, a bridge, deeply rooted in Barbizon Realism but looking towards the more luminous qualities that Impressionism championed.

Artistic Style: Light, Emotion, and the Hungarian Soul

László Paál’s artistic style is characterized by its profound emotional depth and its masterful rendering of light and atmosphere. He was not interested in mere topographical accuracy; rather, he sought to convey the feeling of a place, the soul of the landscape. His canvases are often imbued with a sense of solitude and introspection, a quiet melancholy that speaks to a deep connection with the natural world.

His color palette, while initially more somber and aligned with the Barbizon tradition, gradually lightened, particularly in his depictions of sun-dappled forest paths or clearings. He possessed a remarkable ability to capture the subtle gradations of light filtering through leaves, the dampness of the forest floor after rain, or the hazy glow of a sunset. His brushwork, while generally controlled, could become more vigorous and expressive when depicting the textures of bark, foliage, or earth, hinting at an impressionistic sensibility.

Unlike the French Impressionists who often focused on scenes of modern life or cultivated gardens, Paál remained dedicated to the wilder, more untamed aspects of nature, particularly the forest. His works often feature winding paths, dense thickets, solitary trees, or quiet ponds – motifs that carry symbolic weight, suggesting journeys, introspection, or the cyclical nature of life. There is a distinctly Hungarian sensibility in his work, a certain pensive quality that some critics have linked to the national temperament, even when his subjects were French landscapes. He shared this introspective quality with other Hungarian artists of the period, such as Pál Szinyei Merse, who was pioneering a Hungarian form of plein-air painting and Impressionism around the same time.

Key Works: Echoes of Fontainebleau and Beyond

Several works stand out in László Paál's relatively small but impactful oeuvre. His Fontainebleau Forest series comprises some of his most iconic paintings. Works like Path in the Forest of Fontainebleau (circa 1876) or Road in the Forest of Fontainebleau (1876) exemplify his mature style. These paintings typically feature a path leading the viewer's eye into the depths of the woods, with sunlight breaking through the canopy to illuminate patches of the forest floor. The interplay of light and shadow is rendered with exquisite sensitivity, creating a palpable sense of atmosphere and depth. The trees are not just botanical specimens but characters, their gnarled branches and textured bark conveying age and resilience.

Napemente (In the Thicket), also known as Sunset in the Forest (1871-1872), now housed in the Hungarian National Gallery in Budapest, is another seminal piece. It showcases his early mastery of the Barbizon aesthetic, with its rich, earthy tones and its focus on the dense, almost impenetrable quality of the undergrowth, dramatically lit by the setting sun. The work evokes a sense of mystery and the sublime power of nature.

Other notable works include Village Outskirts (1871), which demonstrates his ability to capture the quiet charm of rural life, and paintings like Dusty Country Road, Cornfield, and In the Barbizon Forest, some ofwhich were painted during his collaborative periods with Munkácsy. While specific details on The Sea, Castle Garden, or Solomis Station are scarce or their attribution to his prime period is uncertain due to his early death, his body of work consistently reflects a preference for tranquil, natural environments. His still lifes, though less numerous than his landscapes, also demonstrate his keen observational skills and his ability to imbue simple objects with a quiet dignity.

Challenges, Recognition, and Hungarian Identity

László Paál's artistic career, though brilliant, was fraught with challenges. He reportedly faced persistent economic difficulties, a common plight for many artists of the era who were not catering to mainstream academic tastes or securing consistent patronage. Personal hardships also cast a shadow over his life, contributing to the melancholic undercurrent found in much of his work.

Despite these struggles, Paál achieved a degree of recognition during his lifetime. He exhibited his works in Paris, including at the prestigious Paris Salon, which was a significant achievement for any artist, particularly a foreign one. His paintings were also shown in Budapest and Vienna, helping to introduce the Barbizon aesthetic to a Central European audience. He was respected within artistic circles, particularly for his dedication to his craft and his profound understanding of nature.

In Hungary, Paál is regarded as a key figure in the development of modern landscape painting. He, along with Munkácsy and Szinyei Merse, helped to steer Hungarian art away from the dominant academicism of figures like Károly Lotz or Bertalan Székely (who were masters in their own right, particularly in historical and mural painting) towards a more direct engagement with nature and contemporary European trends. Paál’s work demonstrated that Hungarian artists could compete on the international stage while still retaining a unique national sensibility. His teaching activities, though perhaps not extensive due to his short life, and his exhibitions in Budapest and potentially other Hungarian art centers like Nagybánya (Baia Mare), contributed to the dissemination of these new artistic ideas.

Collaborations and Artistic Milieu

The most significant artistic relationship in Paál's life was undoubtedly with Mihály Munkácsy. Their friendship was a source of mutual support, both personal and professional. They shared studios, critiqued each other's work, and navigated the complexities of the Parisian art world together. While Munkácsy achieved greater international fame with his dramatic genre scenes and portraits, Paál remained steadfastly devoted to landscape. Their collaboration extended to practical matters, such as the rumored co-authoring of a book on painting techniques, indicating a shared intellectual engagement with their craft.

Beyond Munkácsy, Paál was part of the broader Barbizon circle. While the first generation of Barbizon painters (Rousseau, Millet, Corot) were older, Paál interacted with later adherents and followers of the school. He would have known other artists who frequented Fontainebleau, sharing their commitment to plein-air painting and their reverence for nature. This environment provided a supportive and stimulating milieu for his artistic development. His work can be seen in dialogue with that of other landscape painters of the era, such as the French artist Henri Harpignies, who, like Corot, painted structured yet poetic landscapes, or even the Dutch painters of the Hague School, like Jacob Maris or Anton Mauve, who shared a similar affinity for atmospheric, realist landscapes.

Premature End and Lasting Legacy

Tragically, László Paál's promising career was cut short. He suffered from a debilitating illness, reportedly a brain ailment, which led to his admission to a sanatorium in Charenton-le-Pont, near Paris. He died there in 1879, at the young age of 33. His death was a significant loss for Hungarian and European art.

Despite his short life, László Paál left an indelible mark. His paintings are treasured for their lyrical beauty, their technical mastery, and their profound emotional connection to the natural world. He successfully synthesized the influences of the Barbizon School and French Realism with his own unique vision, creating landscapes that are both timeless and deeply personal.

His legacy endured in Hungary, influencing subsequent generations of landscape painters. The authenticity and emotional depth of his work resonated with artists who sought to develop a distinctly Hungarian modern art. His paintings are prominently featured in the Hungarian National Gallery and other major collections, serving as a testament to his talent and his contribution to art history. He remains a beloved figure, a painter who, through his devotion to the forests of Fontainebleau, captured universal truths about nature, beauty, and the human spirit. His art continues to inspire and move viewers with its quiet power and its enduring celebration of the natural world.

Conclusion: A Poet of the Forest

László Paál was more than just a skilled painter of trees and light; he was a poet of the forest. His canvases invite contemplation, drawing the viewer into a world of tranquil beauty and subtle emotion. He navigated the artistic currents of his time with integrity, absorbing the lessons of Realism and the Barbizon School while forging a path that was uniquely his own. His sensitivity to the nuances of light and atmosphere, combined with his ability to convey deep feeling, set him apart. Though his life was brief, his artistic vision was clear and profound, leaving behind a legacy of landscapes that continue to speak to the enduring power of nature and the artist's unique ability to translate its mysteries into a universal language. László Paál remains a testament to the enduring allure of the landscape and a cherished master of Hungarian art.