Alexandra Alexandrovna Exter stands as a pivotal figure in the tumultuous and exhilarating world of early 20th-century art. Born Alexandra Grigorovich on January 18, 1882, in Białystok, Grodno Governorate, Russian Empire (now Poland), and passing away in Fontenay-aux-Roses, near Paris, on March 17, 1949, her life and career bridged Eastern and Western Europe, tradition and radical innovation. A painter, designer, and educator, Exter navigated and contributed significantly to major avant-garde movements including Cubism, Futurism, Suprematism, and Constructivism, leaving an indelible mark particularly on stage design. Her vibrant, dynamic compositions and multifaceted creative output cemented her legacy as a key "Amazon of the Avant-Garde."

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born into a prosperous Belarusian family, Exter received a privileged upbringing that included private education in languages, music, and art. The family moved to Kyiv, a burgeoning cultural center, where she attended the St. Olga Gymnasium and later, from 1901 to 1903 and again from 1906, the Kyiv Art School (KKHU). While the provided text mentions Alexander Pymonov, it's more likely she studied under or alongside prominent figures associated with the school during that era, perhaps absorbing influences from artists like Mykola Pymonenko, though her primary teachers remain somewhat debated in sources. Her early exposure was likely to the prevailing Realist and Impressionist styles.

In 1908, she married a successful Kyiv lawyer, Nikolai Evgenievich Ekster. This union provided her with financial security and the freedom to pursue her artistic ambitions internationally. The same year, the couple traveled to Paris, marking the beginning of a transformative period for Alexandra. She enrolled at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière in Montparnasse, studying painting. Paris, the undisputed capital of the art world at the time, exposed her to the radical experiments that were reshaping visual culture.

Parisian Immersion and the Rise of Cubo-Futurism

Exter's time in Paris between 1908 and 1914 (with frequent trips back to Kyiv and Moscow) was crucial for her artistic development. She quickly integrated into the vibrant Parisian avant-garde circles. She established friendships with key figures like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, the pioneers of Cubism, whose deconstruction of form and space profoundly impacted her work. She also became close to the poet and art critic Guillaume Apollinaire, who championed the new art, and artists like Sonia Delaunay and Robert Delaunay, whose Orphism explored the dynamic interplay of color and form.

Through these connections, she met Italian Futurists like Ardengo Soffici and Giovanni Papini, and likely encountered the ideas of Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. This confluence of influences – the analytical structure of French Cubism and the dynamism, speed, and vibrant color celebrated by Italian Futurism – led Exter to forge her own distinct style, often termed Cubo-Futurism. This hybrid approach characterized much of the Russian avant-garde during this period.

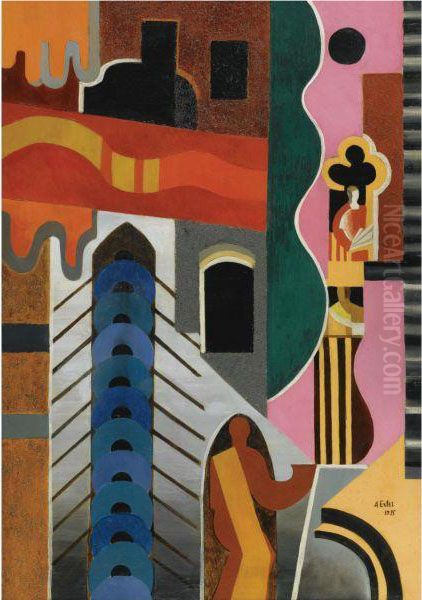

Her studio in Paris became a meeting point for artists and intellectuals. She participated in major Parisian exhibitions, including the Salon des Indépendants and the Salon de la Section d'Or in 1912, showcasing her work alongside the leading modernists. Works like Bridges (Sèvres Bridge) (c. 1912-1914), now housed in the National Art Museum of Ukraine, exemplify this phase. The painting fragments the urban landscape into dynamic, intersecting planes of color, capturing the energy and structure of the modern environment in a distinctly Cubo-Futurist manner.

Kyiv and Moscow: A Hub of Avant-Garde Activity

Exter maintained strong ties with the artistic scenes in Kyiv and Moscow, acting as a vital conduit for transmitting Parisian innovations back to the Russian Empire. Between 1908 and 1914, she traveled frequently, bringing back firsthand knowledge of Cubism and Futurism. In Kyiv, her own studio on Fundukleyevskaya Street became an important intellectual salon and workshop, attracting artists, writers, and poets.

She actively participated in avant-garde exhibitions in Russia, including those organized by the "Jack of Diamonds" group (which included artists like Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov) and the "Union of Youth" in St. Petersburg. In Kyiv, she was a central figure in groups like "Zveno" (Link) and "Koltso" (Ring), organizing exhibitions that featured local avant-garde artists like Alexander Bogomazov and Alexander Archipenko (who was also based in Paris for much of this time).

Her role extended beyond painting and exhibiting. Exter possessed a keen interest in folk art and applied arts. She collaborated with peasant artisans in Ukrainian villages like Verbovka and Skoptsi, encouraging them to create modern designs for embroidery and crafts based on Suprematist principles, working alongside other avant-garde figures like Kazimir Malevich and Liubov Popova in these ventures. This reflected a broader Constructivist impulse to integrate art into everyday life and production.

Suprematism and the Path to Non-Objectivity

While deeply engaged with Cubo-Futurism, Exter's work continued to evolve towards greater abstraction. She was receptive to the radical non-objective art pioneered by Kazimir Malevich, known as Suprematism. In 1915, she participated in the seminal "Tramway V: First Futurist Exhibition of Paintings" in Petrograd (St. Petersburg) and, crucially, the "0.10: The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings" later that same year, where Malevich unveiled his iconic Black Square and the principles of Suprematism.

Exter adopted elements of Suprematism, incorporating pure geometric forms and flat planes of color into her compositions. However, her interpretation often retained a greater sense of dynamism and chromatic richness compared to Malevich's more austere works. Paintings like Venice (1915) showcase this transition, blending Futurist energy and fragmented cityscapes with increasingly abstract, geometrically organized color planes that pulse with rhythm and light. Her engagement with Suprematism further pushed her exploration of pure form and color relationships.

Revolutionizing the Stage: Theatre Design

One of Alexandra Exter's most significant and lasting contributions was in the field of theatre design. Starting around 1916, she began a highly influential collaboration with the director Alexander Tairov at his Kamerny Theatre (Chamber Theatre) in Moscow. Tairov sought to create a "synthetic theatre" that integrated all elements – acting, movement, music, light, set, and costume – into a unified, rhythmic whole. Exter's dynamic, architectural, and non-naturalistic designs were perfectly suited to this vision.

Her designs for productions like Famira Kifared (1916), Salome (1917), and Romeo and Juliet (1921) were revolutionary. She abandoned traditional painted backdrops in favor of multi-levelled, abstract, Constructivist structures. These sets, often resembling complex scaffolding or dynamic assemblages of geometric forms, ramps, and platforms, were designed not just as backgrounds but as active environments that shaped the actors' movements and the play's rhythm. Costumes were equally radical, transforming actors into sculptural, mobile elements within the overall stage composition, often using bold colors and geometric shapes to define character and enhance movement.

Exter treated the stage as a three-dimensional kinetic space. Her use of light was innovative, employed to sculpt the architectural forms of the set and create dramatic atmosphere. This approach fundamentally changed the relationship between performer and environment, influencing theatre design throughout Europe. Her work with Tairov is considered a high point of Constructivist theatre.

Film Design and Constructivist Principles

Exter's design talents extended to the burgeoning medium of film. In 1924, she designed the striking Constructivist costumes for Yakov Protazanov's groundbreaking science fiction film Aelita: Queen of Mars. The Martian costumes, with their sharp angles, metallic sheens, and geometric constructions made from materials like celluloid and metal, vividly brought the futuristic setting to life and remain iconic examples of Constructivist design applied to cinema. They contrasted sharply with the depiction of contemporary Moscow life, highlighting the film's thematic concerns. This project further demonstrated her ability to apply avant-garde principles across different media. Other artists like Isaac Rabinovich, who had been associated with her Kyiv studio, also contributed designs to the film.

Emigration and Later Years in Paris

The years following the 1917 Russian Revolution brought profound changes. While initially many avant-garde artists, including Exter, were involved in cultural activities under the new regime (she taught at the Vkhutemas, the state art and technical school in Moscow, alongside figures like Alexander Rodchenko and Varvara Stepanova), the increasing ideological constraints and shift towards Socialist Realism made creative freedom difficult.

In 1924, Exter emigrated permanently, settling in Paris. This marked a new phase in her career, though perhaps one less visible on the grand stage of avant-garde breakthroughs. She continued to work across various fields. She taught theatre design, notably at Fernand Léger's Académie d'Art Moderne between 1926 and 1930. Léger himself was an artist whose work shared certain affinities with Exter's dynamic, machine-age aesthetic.

She created designs for ballet and theatre productions, though perhaps not with the same revolutionary impact as her Moscow work. A significant part of her later output involved book illustration and the creation of exquisite gouache paintings, often characterized by vibrant color and a refined, sometimes decorative, abstraction that occasionally touched upon Art Deco sensibilities. She produced illustrations for editions of works by authors like Pushkin and Gogol. She also experimented with marionette design, creating detailed and expressive puppets.

Despite her continued activity, her later years were marked by relative obscurity compared to her pre-emigration fame, and she faced financial difficulties. The trauma of World War I, mentioned in the provided text, may have had lasting effects, and her health eventually declined. Alexandra Exter died of leukemia in 1949 in Fontenay-aux-Roses, a suburb of Paris.

Artistic Style: Synthesis and Dynamism

Alexandra Exter's artistic style is characterized by its synthesis of diverse influences and its inherent dynamism. From her early engagement with Impressionism, she rapidly absorbed and transformed Cubism and Futurism. Her Cubo-Futurist works break down objects and scenes into geometric facets, but unlike the often monochromatic palette of early Picasso and Braque, Exter employed rich, vibrant colors, reflecting perhaps the influence of folk art and the Orphism of the Delaunays.

Movement is a key element throughout her oeuvre. Whether depicting urban landscapes, theatrical scenes, or pure abstractions, her compositions are rarely static. Diagonal lines, spiraling forms, and contrasting color planes create a sense of energy, rhythm, and spatial tension. This dynamism reached its zenith in her theatre designs, where the entire stage became a kinetic sculpture.

As she moved towards Suprematism and Constructivism, her work became increasingly non-objective, focusing on the interplay of pure geometric forms and color. Yet, even in her most abstract pieces, there is often a sense of underlying structure and a powerful chromatic sensibility. Her later works, particularly the gouaches, show a continued mastery of color and composition, sometimes with a more lyrical or decorative quality. She remained a superb colorist throughout her career.

Influence and Legacy

Alexandra Exter's influence was multifaceted. As a key participant in the major avant-garde movements, she contributed significantly to their development, particularly Cubo-Futurism and Constructivism. Her role as a bridge between the Parisian avant-garde and the burgeoning modern art scenes in Kyiv and Moscow was crucial for the cross-pollination of ideas in the early 20th century.

Her work in theatre design was profoundly influential, setting new standards for non-naturalistic, dynamic staging that resonated with directors and designers across Europe. Figures like Vsevolod Meyerhold in Russia, though developing his own biomechanics, operated within a similar milieu of theatrical experimentation that Exter helped to shape.

As an educator, both in her Kyiv studio and later in Paris, she nurtured a generation of artists. Students like Pavel Tchelitchew, Isaac Rabinovich, and Vadim Meller went on to have significant careers in painting and design. Her teaching emphasized a rigorous understanding of form, color, and composition, combined with an openness to experimentation.

Today, Alexandra Exter is recognized as one of the most important women artists of the avant-garde period. Her works are held in major museum collections worldwide, including the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, the State Russian Museum in St. Petersburg, and the National Art Museum of Ukraine in Kyiv. Exhibitions and scholarly research continue to shed light on her diverse contributions. She stands alongside contemporaries like Natalia Goncharova, Liubov Popova, Olga Rozanova, and Varvara Stepanova as a testament to the vital role women played in shaping modernist art.

Conclusion: An Enduring Avant-Garde Spirit

Alexandra Exter's career exemplifies the dynamism and internationalism of the early 20th-century avant-garde. From Kyiv to Paris to Moscow, she absorbed, synthesized, and innovated, contributing significantly to painting, theatre, film, and design. Her unique blend of Cubist structure, Futurist energy, Suprematist abstraction, and Constructivist application, all infused with her brilliant sense of color and rhythm, created a body of work that remains compelling and influential. As an artist who constantly crossed boundaries – geographical, stylistic, and disciplinary – Alexandra Exter embodies the restless, forward-looking spirit of modernism. Her legacy endures in her vibrant artworks and her pioneering vision for integrating art into the fabric of modern life.