Alexandra Exter stands as a pivotal figure in the tumultuous and exhilarating world of early 20th-century modern art. Born Alexandra Alexandrovna Grigorovich on January 18, 1882, in Białystok (then part of the Russian Empire, now Poland), and passing away in Fontenay-aux-Roses near Paris on March 17, 1949, Exter's life and career traversed geographical boundaries and artistic movements. She was a painter, a revolutionary stage and costume designer, a book illustrator, and an influential teacher whose work synthesized the innovations of Western European Cubism and Futurism with the unique energy of the Russian and Ukrainian avant-garde, particularly Suprematism and Constructivism. Her dynamic compositions, vibrant palette, and cross-disciplinary approach earned her the moniker "Amazon of the Avant-Garde," placing her alongside other pioneering women artists who reshaped modern visual culture.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Kyiv

Exter spent her formative years in Kyiv, a thriving cultural center within the Russian Empire. Born into a prosperous family – her father a successful Belarusian businessman, Aleksandr Grigorovich, and her mother of Greek origin – she received a privileged upbringing that included private education in languages, music, and drawing. This cosmopolitan background likely fostered her later ease in navigating different cultural environments.

Her formal artistic training began at the Kyiv Art School (KKHU), from which she graduated in 1906. During her studies, she worked under notable artists, including the Ukrainian painter Mykola Pymonenko, known for his genre scenes. Even in these early stages, Kyiv provided a stimulating environment. The city was experiencing its own artistic ferment, and Exter quickly connected with local intellectuals and artists, participating in exhibitions organized by the "Zveno" (Link) group. Her early works from this period show an absorption of Impressionist and Symbolist tendencies, but already hint at a bolder approach to color and form.

Her marriage in 1908 to Nikolai Evgenyevich Ekster, a successful Kyiv lawyer, provided her with financial stability and social connections. Their home, particularly her studio located in the attic at 27 Funduklievskaya Street, became a legendary meeting place for Kyiv's creative elite. Poets, writers, artists, and musicians gathered there, fostering an atmosphere of intense intellectual and artistic exchange that would profoundly shape Exter's development.

Parisian Encounters and the Embrace of Cubism

A crucial turning point came with Exter's travels to Paris, beginning around 1907-1908. She enrolled at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière in Montparnasse, a popular destination for international artists. Paris was the undisputed epicenter of the art world, buzzing with radical new ideas. Exter immersed herself in this environment, quickly establishing connections with the leading figures of the avant-garde.

She formed significant friendships with artists like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, the pioneers of Cubism, as well as Fernand Léger, whose "tubist" style resonated with her own developing interest in dynamic, geometric forms. She also became close to the poet and art critic Guillaume Apollinaire, a key champion of Cubism, and the artist couple Robert Delaunay and Sonia Delaunay, whose Orphism, with its emphasis on pure color and simultaneous contrasts, deeply influenced her palette.

Exter absorbed the principles of Cubism – the fragmentation of objects, the depiction of multiple viewpoints simultaneously, and the flattening of pictorial space. However, she never became a dogmatic follower. Instead, she synthesized Cubist structure with a Fauvist-inspired intensity of color and a burgeoning interest in dynamism that perhaps stemmed from Italian Futurism, with whose proponents like Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and Ardengo Soffici she also established contact during trips to Italy. Her paintings from this period, such as Three Female Figures (c. 1909-10) and Still Life with Vase (c. 1910), demonstrate this fusion.

Crucially, Exter acted as a vital conduit between Paris and the burgeoning avant-garde scenes in Kyiv, Moscow, and St. Petersburg. She regularly traveled back and forth, bringing firsthand knowledge of the latest Parisian developments, exhibiting French art in Russia, and introducing her Russian colleagues' work to the West. Her studio in Kyiv served as a key node in this network, disseminating Cubist and Futurist ideas.

The Kyiv and Moscow Nexus: Cubo-Futurism and Avant-Garde Circles

Between her Parisian sojourns, Exter remained deeply engaged with the artistic life of the Russian Empire. She became a central figure in the Russian avant-garde, exhibiting alongside artists who were forging distinctly local interpretations of modernism. She participated in major exhibitions organized by groups like the "Soyuz Molodyozhi" (Union of Youth) in St. Petersburg and, significantly, the "Bubnovy Valet" (Jack of Diamonds) group in Moscow.

The Jack of Diamonds exhibitions brought together artists like Mikhail Larionov, Natalia Goncharova, Aristarkh Lentulov, Pyotr Konchalovsky, and Ilya Mashkov. These artists shared an interest in French Post-Impressionism (particularly Cézanne) and Fauvism, combined with a fascination for Russian folk art, lubki (popular prints), and shop signs. Exter's work fit well within this context, though her direct engagement with Parisian Cubism gave her a unique perspective.

During the early 1910s, Exter developed her own powerful style often termed Cubo-Futurism. This hybrid approach combined the structural analysis of Cubism with the dynamism, speed, and vibrant color associated with Italian Futurism. Works like Bridge at Sèvres (1912), City at Night (c. 1913), and the paintings inspired by her travels, Florence (1914/15) and Venice (1915), exemplify this phase. They feature fragmented urban landscapes, energetic diagonal lines, intersecting planes, and a dazzling, non-naturalistic palette, conveying the rhythm and intensity of modern life.

Her Kyiv studio continued to be a melting pot. She collaborated with fellow artists, including Alexander Bogomazov and the Burliuk brothers (David and Vladimir), key figures in Ukrainian and Russian Futurism. She also maintained connections with Alexander Archipenko, another Kyiv-born artist who had found success in Paris with his Cubist sculptures. Exter's influence extended beyond painting; she began exploring design, applying her avant-garde principles to decorative objects and even peasant embroideries through workshops she helped organize.

Revolutionizing the Stage: Collaboration with Alexander Tairov

One of Alexandra Exter's most significant and lasting contributions was her revolutionary work in stage and costume design, primarily through her collaboration with the innovative director Alexander Tairov at his Kamerny Theatre (Chamber Theatre) in Moscow, starting around 1916. Tairov sought to create a "synthetic theatre" that integrated all elements – acting, movement, music, text, set, and costume – into a unified, rhythmic whole, breaking away from naturalist conventions. Exter's artistic vision perfectly aligned with his goals.

Her debut at the Kamerny Theatre was with the production of Innokenty Annensky's Thamyris Kitharodos (1916). Her designs were a revelation. Instead of painted backdrops, she created three-dimensional, architectural structures on stage using platforms, ramps, and stairs. These dynamic constructions, influenced by Cubism and anticipating Constructivism, sculpted the stage space and dictated the actors' movements, transforming them into kinetic elements within the overall composition.

Her costumes were equally radical. Rejecting historical accuracy in favor of expressive form and color, she designed sculptural garments that emphasized the actors' plasticity and integrated them into the dynamic stage environment. Vibrant colors, geometric shapes, and unusual materials were combined to create striking visual effects that enhanced the mood and rhythm of the performance.

This groundbreaking approach continued with subsequent productions, most famously Oscar Wilde's Salome (1917) and William Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet (1921). For Salome, she created a dazzling, multi-level set of intersecting planes and rich, jewel-toned costumes that conveyed the play's decadent atmosphere. For Romeo and Juliet, she designed a complex, adaptable structure that could represent various locations through minimal changes, emphasizing the play's dramatic flow. Her costumes blended Renaissance silhouettes with bold, avant-garde geometry.

Exter's theatre designs were highly influential, demonstrating how modern art principles could transform the stage. She effectively treated the stage as a kinetic sculpture and the actors as mobile parts within it. Her work set a new standard for theatrical design in Russia and beyond, directly influencing later Constructivist theatre artists like Liubov Popova, Varvara Stepanova, and Alexander Vesnin. She also collaborated with the choreographer Bronislava Nijinska on ballet projects, further extending her reach in performance design.

Suprematism, Constructivism, and Applied Arts

While deeply involved in theatre, Exter continued her explorations in painting. Around 1915-1916, she came into contact with Kazimir Malevich and his radical new art movement, Suprematism, which advocated for pure, non-objective art based on fundamental geometric forms and limited colors. Exter participated in activities of the Supremus group, organized by Malevich, alongside other key figures like Liubov Popova, Nadezhda Udaltsova, Olga Rozanova, and Ivan Kliun.

Her paintings from the late 1910s reflect this engagement. Works like her Colour Dynamics series (c. 1916-18) and various non-objective compositions feature floating geometric shapes – circles, squares, rectangles, triangles – arranged in dynamic, asymmetrical configurations against a white or colored ground. While sharing Suprematism's non-objectivity, Exter's compositions often retained a greater sense of dynamism and a richer, more complex color palette compared to Malevich's stricter examples, reflecting her enduring interest in movement and rhythm.

The revolutionary period following 1917 saw the rise of Constructivism, an artistic and architectural philosophy that rejected autonomous art in favor of art serving social purposes and contributing to the building of a new society. Many avant-garde artists, including Exter, embraced its principles, channeling their creativity into practical design fields. Exter taught color theory at the influential Vkhutemas (Higher Art and Technical Studios) in Moscow, a crucible of Constructivist thought where artists like Alexander Rodchenko and Vladimir Tatlin also taught.

Her belief in integrating art into life found expression in various applied arts. She designed textiles, experimented with fashion, and continued her work in book illustration. Her interest in folk art traditions also persisted, viewing them as a source of authentic artistic principles that could be synthesized with modernism. This period saw her applying avant-garde aesthetics to a wide range of functional objects, aiming to reshape the visual environment of the new era.

Design Beyond the Stage: Aelita and Later Works

Exter's prowess in design reached a wider audience through her work on the pioneering Soviet science fiction film Aelita: Queen of Mars (1924), directed by Yakov Protazanov. She designed the elaborate and futuristic costumes for the Martian scenes, as well as some of the sets. Her Martian costumes are iconic examples of Constructivist design applied to film. They feature sharp, geometric shapes, metallic fabrics, and unusual structural elements, creating an otherworldly and highly stylized look that perfectly captured the film's futuristic fantasy. The headdresses, in particular, are striking sculptural creations.

This project showcased her ability to adapt her artistic principles to different media and requirements, blending imaginative fantasy with rigorous geometric construction. The Aelita costumes remain some of the most memorable images of early Soviet cinema and avant-garde design.

In 1924, Exter was given the opportunity to design the Soviet pavilions for the Venice Biennale. She traveled to Italy for this purpose and, like many artists facing increasing ideological constraints and economic hardship in the Soviet Union, decided not to return. She settled in Paris, where she would spend the remainder of her life, later moving to the nearby suburb of Fontenay-aux-Roses.

Emigration and the Parisian Years

Life as an émigré artist in Paris presented new challenges. While she was initially well-connected, the artistic landscape had shifted, and the vibrant collective energy of the Russian avant-garde was replaced by the more individualized and commercially oriented Parisian art world. Exter continued to work across multiple disciplines, but financial security often proved elusive.

She taught art, notably for a period at Fernand Léger's Académie d'Art Moderne, sharing her expertise in color and composition. She continued to paint, though her style evolved, sometimes incorporating more figurative elements or a softer, more decorative quality influenced perhaps by Art Deco trends. She found a particular niche in book illustration, creating exquisite hand-painted books (gouaches) and illustrated manuscripts using the pochoir (stencil) technique. These works, often commissioned by bibliophiles, allowed her to continue exploring color and form on an intimate scale.

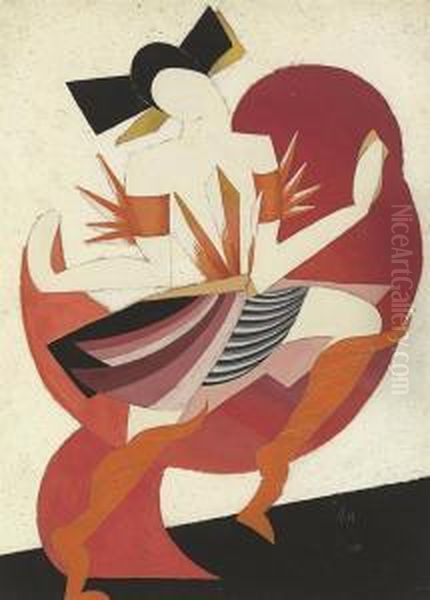

A fascinating project from this period was her creation of marionettes, begun around 1926. These were not traditional puppets but highly stylized, articulated figures designed with the same principles of dynamic construction and geometric form seen in her stage work. Figures like the Spanish Dancer marionette are miniature kinetic sculptures, embodying her enduring fascination with movement and avant-garde aesthetics.

Despite her continued creativity, Exter faced increasing hardship, particularly during the war years and afterwards. She struggled financially and suffered from ill health. Though somewhat isolated from the mainstream art world in her later years, she maintained contact with friends like Sonia Delaunay and continued to work until her death in 1949.

Artistic Style: A Synthesis of Modernisms

Alexandra Exter's artistic style is characterized by its dynamism, vibrant color, and synthesis of multiple avant-garde influences. She possessed an exceptional sensitivity to color, using bold, often non-naturalistic hues to create emotional impact and rhythmic structure. Her compositions are typically energetic, employing diagonal lines, intersecting planes, and fragmented forms derived from Cubism and Futurism to convey movement and the intensity of modern experience.

Her adaptation of Cubism was never purely analytical; she infused it with color and dynamism. Her engagement with Suprematism led to powerful non-objective works, but these often retained a complexity and energy distinct from Malevich's purer forms. In her stage and costume designs, she translated these painterly concerns into three dimensions, creating kinetic environments and sculptural garments that redefined theatrical space.

Throughout her career, Exter demonstrated remarkable versatility, moving fluidly between painting, theatre design, costume design, graphic arts, and teaching. Her work consistently reflects a rigorous approach to form and composition, combined with an intuitive feel for color and rhythm. She successfully bridged the gap between the "fine" arts and applied arts, embodying the Constructivist ideal of the artist as a shaper of the total environment.

Legacy and Influence

Alexandra Exter's position in art history is significant, though for many years she was somewhat overshadowed by her male contemporaries and the political complexities surrounding the Russian avant-garde. She is now recognized as a major innovator and a key figure connecting Western European modernism with the Russian and Ukrainian avant-garde movements. Her role as an "Amazon of the Avant-Garde," alongside artists like Natalia Goncharova, Liubov Popova, Varvara Stepanova, Olga Rozanova, and Nadezhda Udaltsova, highlights the crucial contributions of women to this revolutionary period in art.

Her influence was profound, particularly in the field of stage design. Her work for Tairov's Kamerny Theatre set precedents that resonated throughout 20th-century theatre. Her approach to integrating set, costume, and movement into a unified dynamic whole remains a touchstone for theatrical innovation. Her costume designs, especially for Aelita, continue to inspire fashion and film designers.

As a teacher, both in Kyiv, Moscow (at Vkhutemas), and later in Paris (at Léger's academy), she passed on her sophisticated understanding of color and form to younger generations of artists. Her Kyiv studio's role as an intellectual salon cemented her importance as a catalyst for artistic exchange.

Today, Exter's works are held in major museums worldwide, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, and the National Art Museum of Ukraine in Kyiv. Exhibitions dedicated to her work continue to reveal the depth and breadth of her creativity, securing her legacy as a versatile, innovative, and indispensable figure in the history of modern art. Her life and work stand as a testament to the power of artistic vision to transcend borders and disciplines during a period of profound global change.