Moritz Stifter (1857-1905) was an Austrian painter who carved a distinct niche for himself in the vibrant art world of the late 19th century. Primarily celebrated for his evocative genre scenes and works tinged with the exotic allure of Orientalism, Stifter's art offers a window into the aesthetic sensibilities and cultural currents of his time. Though perhaps not as globally renowned as some of his contemporaries, his contributions to Austrian art, particularly his depictions of everyday life, feminine beauty, and dreamlike allegories, merit closer examination. His lifespan placed him squarely within a period of immense artistic ferment, witnessing the decline of academic traditions and the rise of Impressionism, Symbolism, and Art Nouveau, all of which formed the backdrop to his creative endeavors.

Biographical Sketch and Artistic Milieu

Born in Vienna, the bustling capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in 1857, Moritz Stifter came of age during a period of significant cultural and artistic flourishing. Vienna, at this time, was a crucible of creativity, home to figures who would redefine music, literature, philosophy, and the visual arts. While detailed records of Stifter's early life and formal artistic training are not as extensively documented as those of some other artists, it is known that he pursued his career as a painter within this dynamic environment. He passed away in Mauer-Öhling, Lower Austria, in 1905, leaving behind a body of work that reflects both personal vision and the broader artistic trends of his era.

The late 19th century in Austria, and indeed across Europe, was characterized by a departure from the strictures of academic art. Artists began exploring new modes of expression, new subject matter, and new techniques. The influence of French Impressionism, with its emphasis on light, color, and capturing fleeting moments, was beginning to be felt, although its adoption in Austria took a unique path, often blending with local traditions and a penchant for decorative and symbolic art. Figures like Hans Makart had earlier dominated the Viennese scene with grandiose historical and allegorical paintings, setting a high bar for decorative opulence. As Stifter matured, artists like Gustav Klimt were spearheading the Vienna Secession, challenging conservative art institutions and embracing modernism in its various forms.

Artistic Style and Dominant Themes

Moritz Stifter's artistic output is primarily characterized by genre painting and works influenced by the prevailing Orientalist trend. Genre painting, which depicts scenes from everyday life, was a popular form in the 19th century, offering relatable narratives and intimate glimpses into the lives of ordinary people, or idealized portrayals of romantic or historical settings. Stifter excelled in this domain, often focusing on scenes involving women, domestic interiors, and moments of quiet contemplation or social interaction.

His style often reveals a meticulous attention to detail, particularly in the rendering of fabrics, costumes, and interior settings. There's a certain polish and refinement in his technique, suggesting a solid academic grounding, yet his works also possess a sensitivity and an emotional resonance that transcends mere technical skill. While the provided information links him to "Expressionism and Impressionism," particularly in landscape, this seems to be a point of confusion with the writer Adalbert Stifter. For Moritz Stifter the painter (1857-1905), his known works align more closely with late Romanticism, Academic Realism, and the specific trend of Orientalism, rather than the avant-garde movements of Impressionism or Expressionism as they are typically understood. His handling of light and color, while competent, does not usually display the broken brushwork or plein-air immediacy of the Impressionists.

A significant aspect of Stifter's oeuvre is his engagement with Orientalism. This artistic and cultural phenomenon, which swept across Europe in the 19th century, involved the depiction of subjects and themes derived from North Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. These portrayals were often romanticized, exoticized, and filtered through a Western lens, but they captivated the public imagination and provided artists with a rich source of inspiration for vibrant colors, elaborate costumes, and sensual narratives. Stifter's Orientalist pieces likely featured figures in exotic attire, opulent settings, and themes that evoked a sense of mystery and distant lands, aligning with the work of prominent Orientalist painters like Jean-Léon Gérôme or Ludwig Deutsch.

Representative Works: A Closer Look

Several works are frequently cited as representative of Moritz Stifter's artistic concerns and stylistic approach. These paintings offer valuable insights into his thematic preoccupations and his skill as a visual storyteller.

"Allegory of Dream" (Allegorie der Träume)

One of Stifter's most intriguing and discussed works is "Allegory of Dream." The provided information dates this piece to circa 1868. If this date is accurate for Moritz Stifter, it would mean he created this complex allegorical work at the remarkably young age of eleven. This dating might be a point of confusion or refer to an earlier study, as the thematic maturity and technical execution often seem more aligned with a later period in an artist's career. Regardless of the precise dating, the painting itself is a powerful exploration of the subconscious. It reportedly depicts a man and a woman suspended in mid-air, locked in a passionate embrace. This imagery symbolizes the liberation of the soul in dreams, where desires, ambitions, and experiences beyond the grasp of waking reality can unfold. The work touches upon themes of romantic fantasy, the ephemeral nature of dreams, and the uninhibited expression of emotion, suggesting a connection to the Romantic and Symbolist undercurrents that valued imagination and the inner world.

"New Dress" (Das neue Kleid)

Dated to 1889, "New Dress" is a quintessential example of Stifter's genre painting. The artwork portrays a scene likely set in a dressmaker's shop or a domestic interior where women are engaged with the creation or admiration of a new garment. The inclusion of a sewing machine, a relatively modern invention for the time, grounds the scene in contemporary life. Such paintings often celebrated feminine domesticity and craftsmanship, while also allowing the artist to showcase his skill in rendering textures, fabrics, and the subtle interplay of figures within an interior space. This work would have resonated with a bourgeois audience appreciative of scenes that reflected their own lives and aspirations, or at least an idealized version thereof.

"Nymph" or "Maiden" (Nymphe/Mädchen)

Works like "Nymph" or "Maiden," with one version dated to 1887, demonstrate Stifter's engagement with mythological and classical themes, often intertwined with an appreciation for the female form and its connection to nature. Nymphs, in Greek mythology, are female deities associated with natural settings like forests, springs, and mountains. Stifter's depictions would likely have portrayed these figures as graceful, often ethereal beings, embodying ideals of beauty and natural innocence. Such subjects were popular in academic and Salon art, allowing for a blend of classicism, romanticism, and often a subtle sensuality. These paintings highlight his ability to create idealized figures and imbue them with a sense of timeless charm.

"Two Girls Singing On A Bench In A Park"

This title suggests a charming genre scene, capturing a moment of leisure and youthful companionship. Parks were increasingly important social spaces in 19th-century urban life, and scenes set within them offered opportunities to depict contemporary fashion, social interactions, and the beauty of cultivated nature. Stifter's treatment of such a subject would likely emphasize the innocence and grace of the young women, the pleasant atmosphere of the park, and perhaps a touch of romantic sentimentality.

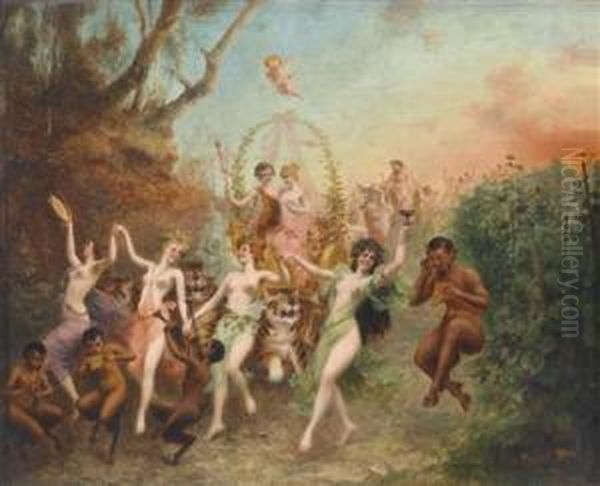

"Festival of Fauns and Nymphs"

Expanding on his interest in mythological subjects, a "Festival of Fauns and Nymphs" would allow Stifter to explore more dynamic and celebratory compositions. Fauns (or satyrs) and nymphs are staples of classical mythology, often associated with Bacchic revels, pastoral landscapes, and the untamed aspects of nature. Such a theme provided ample scope for depicting movement, joyous abandon, and the interplay of numerous figures in a lush, imaginative setting. This type of work aligns with a long tradition in European art of depicting mythological festivities, seen in the works of artists from Titian to Poussin, and later reinterpreted by 19th-century painters.

The Influence of Orientalism in Stifter's Art

The allure of the "Orient" was a powerful force in 19th-century European art, and Moritz Stifter was among the many artists who responded to its call. This fascination was fueled by colonial expansion, increased travel, archaeological discoveries, and widely circulated illustrated publications. For artists, the East offered a vibrant palette, exotic costumes, different architectural styles, and narratives that seemed to promise sensuality, adventure, and a departure from the perceived mundanity of European life.

While specific titles of Stifter's overtly Orientalist works are not extensively detailed in the provided summary, his association with this trend suggests that he produced paintings featuring subjects such as odalisques, harem scenes, bustling marketplaces, or figures in traditional Middle Eastern or North African attire. These works would have catered to a public eager for glimpses into these distant and often romanticized cultures. Artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme, Eugène Delacroix, John Frederick Lewis, and the Austrian-born Rudolf Ernst were leading figures in this genre, creating highly detailed and often dramatically charged scenes. Stifter's contributions would have been part of this broader European artistic engagement with the East, reflecting its aesthetic appeal and thematic possibilities.

Stifter and His Contemporaries: A Crowded Canvas

Moritz Stifter worked during a period rich with artistic talent, both in Austria and internationally. Understanding his place requires acknowledging the diverse artistic landscape of his time.

In Vienna itself, Hans Makart (1840-1884) was an immensely influential figure in the preceding generation, known for his opulent, large-scale historical and allegorical paintings that defined an era of Viennese art known as the "Makartstil." While Stifter's genre scenes were generally more intimate, Makart's emphasis on sensuousness and decorative richness may have had some ambient influence.

Emerging during Stifter's active years was Gustav Klimt (1862-1918), who would become a leading figure of the Vienna Secession and Art Nouveau. Klimt's opulent, symbolic, and often erotic works, with their gold leaf and intricate patterns, represented a more avant-garde direction. While different in style, both artists shared an interest in depicting the female form, albeit with vastly different approaches and philosophies. Other Secessionists like Koloman Moser (1868-1918) and later Egon Schiele (1890-1918) and Oskar Kokoschka (1886-1980), though largely of the next generation, pushed Viennese art into even more radical Expressionist territories.

Beyond Austria, the international art scene was vibrant. In France, Impressionism had already made its mark with artists like Claude Monet (1840-1926), Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), and Edgar Degas (1834-1917), who focused on capturing light, atmosphere, and modern life. Post-Impressionists like Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) and Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) were exploring more personal and symbolic modes of expression. Gauguin's own fascination with exotic cultures, particularly Tahiti, offers an interesting parallel to the Orientalist trend, though his approach was more deeply immersive and critical of European society.

In the realm of academic and Salon painting, artists like William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825-1905) in France and Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836-1912) in Britain continued to produce highly polished, often classical or historical scenes that were immensely popular with the public and collectors. Stifter's more refined genre pieces and mythological works share some common ground with this tradition in terms of technique and subject matter.

The Symbolist movement, which emphasized dreams, emotions, and mystical themes, also flourished during this period, with artists like Odilon Redon (1840-1916) in France and Arnold Böcklin (1827-1901) in Switzerland creating evocative and often unsettling imagery. Stifter's "Allegory of Dream" certainly resonates with Symbolist preoccupations.

In Germany, artists like Max Liebermann (1847-1935) were pioneers of German Impressionism, while Franz von Stuck (1863-1928) and Max Klinger (1857-1920), Stifter's direct contemporary, were prominent figures in Symbolism, often exploring mythological and psychological themes with a distinctive Germanic intensity. Klinger, in particular, was known for his intricate print cycles and sculptures that delved into complex allegories.

The provided text also mentions a list of contemporaries including "Angell, Renoir, Delacroix, Francois Pierre Michetti, Edouard de Beaumont de Pastoret, Urio Rosati." While Renoir and Delacroix (who died in 1863, when Stifter was a child, but whose influence persisted) are major figures, the others are less universally known but represent the breadth of artistic activity in the 19th century. For instance, Francesco Paolo Michetti (1851-1929) was an Italian painter known for his vibrant genre scenes and portraits.

Exhibitions, Collections, and Legacy

Information regarding specific major exhibitions during Moritz Stifter's lifetime is somewhat limited in the provided summary. However, it is noted that his works have appeared in auctions, indicating their circulation within the art market. For example, a work was listed in a KUNSTAUKTION auction catalog (November 2023), and his painting "New Dress" was mentioned in connection with an 1889 context, possibly an exhibition or publication.

The Segantini Museum in St. Moritz is mentioned as having exhibited his work. This museum is primarily dedicated to the Alpine painter Giovanni Segantini, a contemporary who worked in a Divisionist style, so an exhibition of Stifter's work there would suggest a thematic or regional connection, or a temporary show. Furthermore, it's stated that some unpublished works by Stifter can be seen at the Ludwig Galerie Schloss Oberhausen . This suggests that institutional collections do hold examples of his art.

Today, Moritz Stifter's paintings are appreciated by collectors of 19th-century European art, particularly those interested in Austrian genre painting and Orientalist themes. Reproductions of his works, such as canvas prints of his "Nymphs," are available, indicating a continued, if modest, public interest. His art provides valuable examples of the tastes and artistic currents of late 19th-century Vienna, a city at the crossroads of tradition and modernity.

While he may not have been a radical innovator in the vein of the Secessionists, Stifter contributed to the rich tapestry of Viennese artistic life through his skilled execution, his appealing subject matter, and his engagement with popular themes like everyday life, feminine beauty, mythology, and the exotic. His works serve as a reminder of the diversity of artistic production that coexisted during this dynamic period, appealing to a clientele that valued narrative clarity, technical accomplishment, and romantic or intriguing subjects.

Conclusion: Reappraising Moritz Stifter

Moritz Stifter (1857-1905) remains a noteworthy figure within the Austrian art historical narrative of the late 19th century. His paintings, characterized by their detailed execution and thematic focus on genre scenes, idealized female figures, mythological narratives, and Orientalist visions, reflect the prevailing tastes and cultural fascinations of his time. Works like "Allegory of Dream," "New Dress," and his various depictions of nymphs and maidens showcase his technical skill and his ability to imbue his subjects with charm and emotional depth.

Situated in a Vienna teeming with artistic giants and revolutionary movements, Stifter pursued a path that, while perhaps less radical than some of his contemporaries, resonated with a significant segment of the art-loving public. His engagement with Orientalism connected him to a broader European trend, while his genre scenes offered intimate and relatable portrayals of contemporary or idealized life. By examining his art, we gain a fuller understanding of the multifaceted artistic landscape of Austria-Hungary before the seismic shifts of the early 20th century. Though further research might unearth more details about his life and a more comprehensive catalogue of his works, Moritz Stifter's legacy endures through the paintings that continue to capture the imagination and offer a glimpse into a bygone era.