Delphin Enjolras stands as a significant figure in French Academic painting, an artist whose career bridged the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Born in 1857 and living until 1945, he became renowned for his intimate and elegant portrayals of young women, captured in moments of quiet domesticity. His work is celebrated for its technical skill, particularly its masterful handling of light, and its gentle, poetic atmosphere. While perhaps less revolutionary than some of his contemporaries, Enjolras carved a distinct niche for himself, creating images that continue to charm viewers with their beauty and tranquility.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Léon-Delphin Enjolras was born on May 13, 1857, in Courcouron, a small commune in the Ardèche region of southern France. From an early age, he displayed a natural aptitude for drawing and art. His foundational education took place in nearby Puy-en-Velay. Recognizing his talent, he eventually made his way to Paris, the epicenter of the art world, to pursue formal training.

In Paris, Enjolras enrolled at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts. This institution was the bastion of Academic tradition, emphasizing rigorous training in drawing, composition, and the study of Old Masters. While the provided source material mentions Théodore Géricault and Gaston Gérard as teachers, this appears inaccurate due to chronology (Géricault died in 1824) and prominence. It is far more likely and historically documented that Enjolras studied under influential figures such as the celebrated Orientalist and Academic master Jean-Léon Gérôme, known for his meticulous detail and historical scenes.

Another significant influence during his formative years was likely Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret, a painter admired for his Naturalist scenes and sensitive portrayals of peasant life, often imbued with a subtle luminosity. Training under such accomplished artists provided Enjolras with a strong technical foundation in drawing, anatomy, and the traditional methods of oil painting, which would serve him throughout his career. He also studied watercolor painting early on, developing a versatility in different mediums.

A Shift in Focus: From Landscapes to Intimate Interiors

Like many artists beginning their careers, Enjolras initially explored landscape painting. The French landscape tradition was rich, extending from the Barbizon School painters like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot to the burgeoning Impressionist movement. However, Enjolras soon found his true calling not in the expansive outdoors, but in the intimate, often artificially lit, world of interior scenes populated by elegant young women.

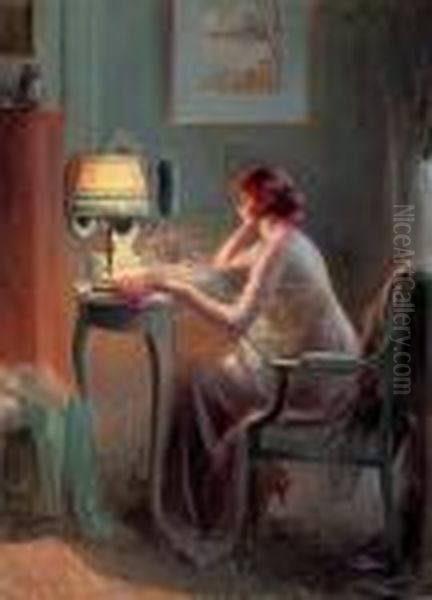

This shift marked the defining characteristic of his mature work. He turned his attention almost exclusively to depicting women engaged in quiet, everyday activities: reading a letter, absorbed in a book, sewing by lamplight, lost in thought (reverie), or simply relaxing in elegantly appointed rooms. These subjects allowed him to focus on capturing subtle nuances of mood, texture, and, most importantly, the effects of light.

His chosen subject matter placed him within a popular genre of the time, catering to the tastes of the bourgeois collectors who frequented the Paris Salon. Artists like James Tissot and Alfred Stevens also found success depicting fashionable women in contemporary settings, though Enjolras developed a distinct style focused more on intimacy and the play of light than on social commentary or high fashion.

The Signature Style: Light, Elegance, and Atmosphere

The hallmark of Delphin Enjolras's art is his extraordinary ability to render light, particularly artificial light. He became known as a "painter of reflections," adept at capturing the warm glow cast by oil lamps, candles, or fireplaces onto figures, fabrics, and polished surfaces. This mastery of chiaroscuro – the contrast between light and dark – creates a sense of intimacy, warmth, and sometimes mystery in his paintings.

His interiors are often bathed in a soft, suffused radiance emanating from a single dominant light source. This focused illumination highlights the central figure, drawing the viewer's eye, while allowing the surrounding areas to recede into gentle shadow. The light models the form of the woman, defines the texture of her dress – often silks or satins that catch the light beautifully – and creates a serene, contemplative mood.

Enjolras typically employed a warm color palette, favoring reds, oranges, golds, and creamy whites, which enhanced the cozy atmosphere of his lamplit scenes. His brushwork, while precise in the Academic tradition, could also be fluid and suggestive, particularly in rendering fabrics and backgrounds. The overall effect is one of elegance, tranquility, and idealized feminine beauty. His figures are graceful, poised, and often seem lost in their own private world, inviting the viewer to share a quiet moment.

Themes of Domesticity and Femininity

Enjolras's work consistently revolves around themes of domesticity, quietude, and idealized femininity. His subjects are almost always young, beautiful women depicted within the confines of a comfortable interior. These are not grand historical or mythological narratives, such as those favored by older Academic painters like Alexandre Cabanel, but rather intimate glimpses into everyday life, elevated by a sense of poetry and grace.

The act of reading is a particularly recurrent motif. Women are shown engrossed in books or letters, suggesting education, introspection, and a rich inner life. This portrayal countered some prevailing stereotypes and presented women in moments of quiet intellectual engagement. Sewing and other needlecrafts also feature prominently, traditional feminine pursuits depicted with elegance rather than mere domestic drudgery.

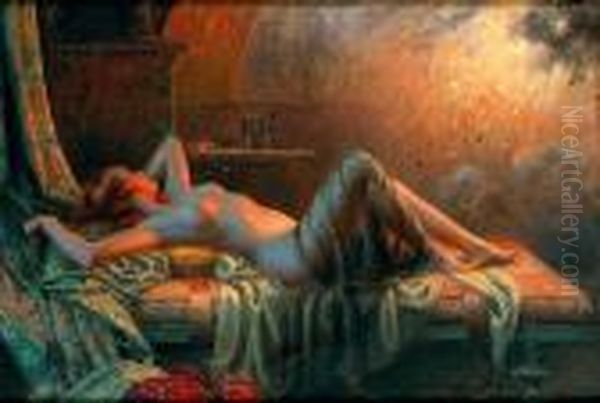

While many of his works depict fully clothed women in refined settings, Enjolras also painted nudes. These works, often featuring a model warming herself by a fireplace or reclining sensuously in a softly lit room, retain his characteristic focus on light and atmosphere. They are sensual rather than overtly erotic, emphasizing the beauty of the female form as revealed by the play of light and shadow, continuing a long tradition in French art but rendered with his signature intimate style.

Mastery Across Mediums: Pastel, Oil, and Watercolor

A testament to his technical skill, Enjolras was proficient in several mediums, choosing the one best suited to the desired effect. He is perhaps most famous for his work in pastels. This medium, with its soft, powdery texture and potential for vibrant color, perfectly suited his interest in subtle light effects and delicate rendering of fabrics and flesh tones. Pastels allowed for a softness and immediacy that enhanced the intimate quality of his scenes.

However, Enjolras was also an accomplished oil painter. His oils often possess a greater depth and richness of color compared to his pastels. He used the layering possibilities of oil paint to build up luminous surfaces and achieve complex effects of light reflecting on different textures – wood, fabric, skin. His training under masters like Gérôme would have grounded him thoroughly in oil techniques.

He also continued to utilize watercolor, likely leveraging its transparency and fluidity for specific effects, perhaps in preparatory studies or for works requiring a lighter, more airy feel. This versatility allowed him to explore his preferred themes with a range of expressive possibilities, consistently achieving a high level of technical finish and aesthetic appeal across different mediums.

Career Success and Recognition: The Paris Salon

Enjolras achieved considerable success during his lifetime. He began exhibiting his work regularly at the prestigious Paris Salon, organized by the Société des Artistes Français, starting around 1890. The Salon was the primary venue for artists to gain recognition and patronage in the late 19th century, despite the emergence of independent exhibitions by groups like the Impressionists (Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas).

His appealing subject matter and technical proficiency resonated with the Salon juries and the public. In 1901, his standing within the official art establishment was confirmed when he became a member of the Société des Artistes Français. This membership signified peer recognition and cemented his status as a successful Academic painter.

His paintings were popular not only in France but also found buyers internationally. They appealed to collectors seeking beautifully executed, decorative works that celebrated feminine grace and domestic tranquility. Today, his works are held in museum collections, including the Musée Crozatier in Puy-en-Velay and the Musée Calvet in Avignon, as well as in numerous private collections worldwide, attesting to his enduring popularity.

Enjolras in the Context of His Time

To fully appreciate Delphin Enjolras, it's essential to place him within the dynamic art world of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He worked during a period of intense artistic innovation and stylistic diversity. While the Impressionists had already challenged Academic conventions with their focus on capturing fleeting moments, light, and color en plein air, Academic painting continued to thrive, supported by the École des Beaux-Arts and the Salon.

Enjolras represented a continuation of this Academic tradition, emphasizing draftsmanship, finished surfaces, and idealized subjects. His work shares affinities with other successful Salon painters like William-Adolphe Bouguereau, who also specialized in idealized female figures, though Enjolras's focus was more on intimate genre scenes than Bouguereau's mythological or allegorical subjects. His attention to light might distantly echo aspects of Impressionism or the work of artists like Anders Zorn, but his technique remained fundamentally Academic and Realist.

He largely remained apart from the radical experiments of Post-Impressionism (Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh, Georges Seurat) or the bold colors of Fauvism (Henri Matisse, André Derain) that emerged in the early 20th century. Enjolras maintained his focus on refined technique and charming subject matter, offering an alternative vision of beauty rooted in tradition and intimate observation. His dedication to this specific genre, executed with consistent skill, defined his contribution.

Notable Works and Recurring Themes

While Enjolras produced a significant body of work, certain compositions and themes are particularly representative. La Jeune Fille à la fenêtre (Young Woman Reading by a Window) is often cited as one of his most characteristic and famous works, or at least a recurring and popular theme. These paintings typically depict a young woman seated near a window, often illuminated by the soft, natural light filtering in, contrasting with his more frequent use of artificial light. The subject is usually absorbed in reading, embodying quiet contemplation.

Other typical titles reflect his recurring interests: The Letter, suggesting anticipation or private communication; Reverie, capturing moments of introspection; By Lamplight or At the Fireside, emphasizing his signature use of artificial light sources; and various Nude studies, showcasing his skill in rendering the female form within intimate settings.

The concept of "serialization," mentioned in the source material, likely refers to his practice of revisiting these favoured themes and compositions multiple times, creating variations on a successful formula. This was not uncommon among popular artists of the era, allowing them to meet market demand while subtly exploring different nuances of light, pose, or mood within a familiar framework. Each variation, while similar in subject, would possess unique qualities in its execution.

Legacy and Art Historical Significance

Delphin Enjolras occupies a respected place in French art history as a master of the intimate genre scene and a skilled exponent of Academic technique, particularly renowned for his handling of light. While the major narratives of art history often focus on the avant-garde movements that broke with tradition, artists like Enjolras played a vital role in the artistic landscape of their time, satisfying a significant public appetite for beauty, elegance, and technical skill.

His influence lies less in groundbreaking innovation and more in the perfection of a specific type of painting. He captured a particular vision of femininity and domestic tranquility that resonated deeply with his contemporaries and continues to appeal to viewers today. His work stands as a testament to the enduring allure of well-crafted, evocative images that celebrate quiet moments and idealized beauty.

He successfully navigated the art world of his era, achieving recognition through the established Salon system. His paintings serve as important examples of late Academic art, demonstrating how traditional techniques could be applied to modern life subjects, albeit in a highly idealized manner. His focus on light effects, particularly artificial light, showcases a specific technical mastery that distinguishes his work.

Conclusion: The Enduring Charm of Enjolras

Delphin Enjolras's art offers a window into a world of quiet elegance and refined beauty. As a "painter of reflections," he masterfully manipulated light to create intimate, atmospheric scenes centered on the grace of young women in domestic settings. Though working within the Academic tradition during a time of revolutionary artistic change, he developed a distinctive and highly popular style characterized by technical polish, warm palettes, and serene moods. His paintings, whether rendered in the soft glow of pastel or the rich depth of oil, continue to captivate viewers with their timeless charm, technical brilliance, and celebration of tranquil moments. He remains an important figure for understanding the diversity of French art at the turn of the 20th century and the enduring appeal of skillfully rendered, beautiful imagery.