Louis Carrogis Carmontelle stands as a fascinating figure in the vibrant cultural landscape of 18th-century France. Born in Paris on August 15, 1717, and living until December 26, 1806, his life spanned a period of immense social, political, and artistic transformation, from the height of the Rococo to the aftermath of the French Revolution and the rise of Napoleon. Carmontelle was far more than just a painter; he was a true polymath – a playwright, architect, landscape designer, inventor, and master of ceremonies, whose diverse talents reflected the intellectual curiosity and innovative spirit of the Enlightenment. Though perhaps less universally known today than some of his contemporaries, his contributions were significant, leaving behind a rich legacy of visual art, theatrical innovation, and pioneering design.

Early Life and Formation

Carmontelle's origins were modest. Born Louis Carrogis, the son of a Parisian shoemaker, he lacked the advantages of aristocratic birth or formal artistic training through the established academies. However, driven by innate talent and determination, he embarked on a path of self-education. He demonstrated an early aptitude for drawing and geometry, skills that would prove foundational to his varied career. By the age of 23, his proficiency in these areas led him to qualify as an engineer, a practical profession that nonetheless hinted at his underlying artistic and design sensibilities. This technical background likely informed the precision evident in much of his later work, from detailed portraits to intricate garden plans and mechanical devices.

His entry into the world of the French aristocracy began not through grand commissions, but through teaching. He found employment tutoring the children of noble families, notably serving the Duc de Chevreuse and the Duc de Luynes at the Château de Dampierre. Here, he instructed his pupils in drawing and mathematics, gaining valuable access to the refined circles of the French elite. This period allowed him to observe aristocratic life firsthand, honing his skills and building connections that would shape his future career. It was a stepping stone from his humble beginnings towards the influential positions he would later hold.

Patronage and Court Life: The House of Orléans

Carmontelle's most significant and enduring professional relationship was with the House of Orléans, one of the most powerful and influential noble families in France. He entered the service of Louis Philippe I, Duke of Orléans (often referred to as "le Gros"), initially perhaps through his teaching connections. His role evolved significantly, becoming far more than just an instructor. He was appointed as a lecteur, an official reader and educator, responsible for the intellectual development of the Duke's son, Louis Philippe Joseph d'Orléans (later known as Philippe Égalité, father of the future King Louis-Philippe I).

Beyond formal education, Carmontelle became the chief organizer of entertainments and festivities for the Duke's household, particularly at their residences like the Palais-Royal in Paris and the Château de Saint-Cloud. This role placed him at the heart of aristocratic social life, requiring immense creativity and organizational skill. He staged theatrical performances, designed elaborate settings, and orchestrated events that showcased his multifaceted talents. His position provided him with unparalleled access to the leading figures of the day – nobles, artists, musicians, writers, and visiting dignitaries – many of whom would become subjects for his prolific portraiture. This immersion in courtly life deeply informed his artistic output, providing both subject matter and a sophisticated audience.

His service to the Orléans family continued for decades, solidifying his reputation within high society. He was not merely an employee but a trusted figure who contributed significantly to the cultural life of the household. His ability to navigate this complex social environment while simultaneously pursuing his diverse artistic interests speaks volumes about his adaptability and charm. The patronage of the Orléans family was crucial, providing him with the resources, opportunities, and stability to develop his unique blend of artistic and practical skills.

The Portraitist of an Era

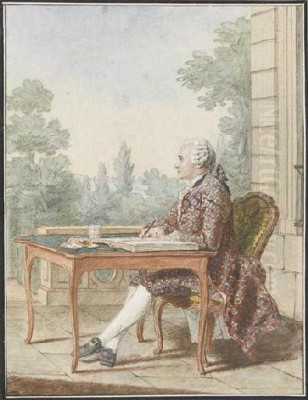

While Carmontelle excelled in many fields, he is perhaps best remembered today for his distinctive portraits. Over his long career, he produced an astonishing number of works, estimated at over 750, primarily profile portraits executed in watercolor and chalks, often heightened with gouache. These were not grand, formal oil paintings in the tradition of artists like Hyacinthe Rigaud or Nicolas de Largillière, but rather more intimate, rapidly executed likenesses that captured the sitter's character and contemporary fashion with remarkable immediacy.

His preferred format was the full-length profile, set against a minimal or suggestive background, often just a wash of color or a hint of an interior or landscape setting. This focus on the profile view, reminiscent of classical medallions or silhouettes, allowed for clear identification and a certain elegant detachment. Yet, Carmontelle imbued these profiles with life through meticulous attention to detail in clothing, posture, and accessories, offering invaluable insights into the fashions and social customs of the Ancien Régime. He captured the nuances of silk, lace, powdered wigs, and elaborate coiffures with a delicate, precise hand.

His subjects were drawn primarily from the elite circles he frequented: members of the Orléans family and their extensive entourage, visiting foreign nobles, prominent intellectuals, actors, dancers, and musicians. His portraits collectively form a visual chronicle of French high society in the decades leading up to the Revolution. Among his most famous sitters was the young Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. During the Mozart family's visit to Paris in 1763-64, Carmontelle captured the seven-year-old prodigy seated at the harpsichord, with his father Leopold standing behind him playing the violin, and his sister Maria Anna ("Nannerl") singing. This iconic image remains one of the most recognizable depictions of the young composer and his family.

Other notable figures immortalized by Carmontelle include the playwright and wit Alexis Piron, the influential salonnière Madame d'Épinay, and members of prominent families like the Rohans and the Contis. He also documented figures reflecting the era's global connections, such as portraits of individuals of African descent within the French aristocracy, like the Chevalier de Saint-Georges (though his most famous portrait is by Mather Brown) or figures associated with colonial interests, providing rare visual records of cross-cultural presence in Parisian society.

The largest single collection of Carmontelle's portraits, numbering nearly 500, is housed today at the Musée Condé in Chantilly, having been acquired by the Duc d'Aumale in the 19th century. This remarkable ensemble offers an unparalleled panorama of French society during his time. While his style might seem less dramatic than the full-blown Rococo of François Boucher or Jean-Honoré Fragonard, or less psychologically intense than the pastels of Maurice Quentin de La Tour, Carmontelle's portraits possess a unique charm, clarity, and documentary value that secure his place as a significant portraitist of the Enlightenment. His work provides a more candid, less idealized glimpse into the lives of his subjects compared to the often more flattering or allegorical approaches of some contemporaries like Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun.

Innovator in Garden Design: Parc Monceau

Carmontelle's creativity extended beyond the canvas and the stage into the realm of landscape architecture. Commissioned by his patron, Louis Philippe Joseph d'Orléans (then Duc de Chartres, later Duc d'Orléans and Philippe Égalité), he designed the celebrated Parc Monceau in Paris between 1773 and 1778. This garden represented a significant departure from the formal, symmetrical French garden style perfected by André Le Nôtre at Versailles a century earlier. Instead, Parc Monceau embraced the newer, fashionable jardin pittoresque or picturesque landscape garden style, inspired by English models and a romanticized vision of nature.

The concept behind Parc Monceau was ambitious and theatrical. Carmontelle envisioned it as "a land of illusions," a place where visitors could encounter scenes from different times and places within a single landscape. He filled the park with an eclectic array of architectural follies – miniature, often non-functional structures designed to evoke specific moods or historical associations. These included a Dutch windmill, an Italian vineyard, a Swiss farm, Egyptian pyramids, classical Roman colonnades, Gothic ruins, a Tartar tent, and Chinese bridges. This collection of disparate elements aimed to surprise, delight, and educate the visitor, offering a journey through a fantasy world.

Carmontelle described his intentions in a publication accompanying the garden's opening, emphasizing the creation of varied scenes and unexpected vistas. The layout was deliberately irregular, with winding paths, artificial hills, grottoes, and carefully placed water features designed to mimic natural landscapes, albeit in a highly curated and artificial manner. This approach contrasted sharply with the rigid geometry, clipped hedges, and grand axes of the traditional French formal garden. Carmontelle's design reflected Enlightenment ideals of variety, sentiment, and a connection to nature, influenced perhaps by the landscape paintings of artists like Claude Lorrain or Hubert Robert, known for his depictions of romantic ruins integrated into natural settings.

Parc Monceau was an immediate sensation, becoming one of the most talked-about gardens in Europe. It exemplified the shift in aesthetic taste towards the picturesque and the exotic. While the garden has undergone significant alterations over the centuries, particularly during the Second Empire under Baron Haussmann, some of Carmontelle's original spirit and a few follies (like the pyramid and the Naumachia colonnade) still remain. His work at Parc Monceau places him alongside other innovators in landscape design, contributing significantly to the development of the French picturesque garden and influencing subsequent park designs. It showcased his ability to translate his artistic vision into a large-scale, immersive environmental experience.

Theatrical Ventures: Proverbes Dramatiques

Carmontelle's engagement with the theatre was deep and multifaceted. He was not only a designer of sets and costumes for the entertainments at the Orléans court but also a prolific playwright. He is credited with popularizing, if not inventing, a specific theatrical genre known as the proverbe dramatique (dramatic proverb). These were short, light comedies, typically in one act, designed for performance in intimate, private settings like aristocratic salons or private theatres, rather than the large public stages dominated by the Comédie-Française or Comédie-Italienne.

The proverbes dramatiques usually revolved around a well-known proverb or maxim, which the play illustrated through witty dialogue, amusing situations, and relatable character types drawn from contemporary society. They often featured elements of social satire, gentle moralizing, and clever wordplay, reflecting the sophisticated tastes of their intended audience. The emphasis was on naturalistic conversation and character interaction rather than grand dramatic action or complex plots. Carmontelle's background as an observer of social manners in his portraiture undoubtedly informed his ability to create convincing and humorous characters for the stage.

He wrote an estimated 130 of these plays, which were performed frequently within the Orléans circle, often featuring members of the household, including the Duke's children and associates, as amateur actors. This participatory aspect added to their charm and exclusivity. Carmontelle himself often directed these performances, contributing to the lively, sometimes improvisational feel that characterized the genre. His plays were eventually collected and published in several volumes between the 1760s and 1780s, such as Proverbes dramatiques (1768-1781) and Théâtre de campagne (Theatre for the Countryside), making them accessible to a wider audience and influencing other writers.

His theatrical work connected him with prominent figures in the performing arts world. For instance, he wrote pieces for the private theatre of the famous dancer Marie-Madeleine Guimard, a leading star of the Paris Opéra known for her lavish lifestyle and artistic patronage. Carmontelle's proverbes offered a lighter, more adaptable form of entertainment compared to the grand tragedies of Voltaire or the complex comedies of Beaumarchais, fitting perfectly into the social fabric of salon culture and private aristocratic amusement. They represent a significant contribution to the diverse theatrical landscape of the late Ancien Régime, showcasing his wit and understanding of social dynamics.

A Precursor to Cinema: The Transparencies

Perhaps Carmontelle's most forward-looking innovation was his development of "transparencies" (transparents), a form of visual entertainment that can be considered an early precursor to moving pictures. These were long scrolls of translucent paper, sometimes extending over 40 meters (around 130 feet), onto which Carmontelle painted continuous landscapes or sequences of scenes using watercolor, gouache, and ink. These scrolls were mounted on rollers within a specially constructed viewing box. When backlit by candles or oil lamps, and slowly cranked from one roller to the other, the transparencies created the illusion of movement – a journey through a changing landscape, the progression of seasons, or a series of unfolding events.

This ingenious device combined Carmontelle's skills as a painter, designer, and inventor. The effect was magical for audiences of the time, offering a novel form of visual storytelling that simulated travel or the passage of time. He created several such transparencies, depicting scenes from his own Parc Monceau, imaginary landscapes, pastoral scenes, and urban views. One notable example, Les Quatre Saisons (The Four Seasons), depicted the changing aspects of a landscape throughout the year. Another showed landscapes of the Île-de-France region.

The transparencies were often accompanied by music or narration, enhancing the immersive experience. They were shown in intimate settings, captivating viewers with their delicate artistry and the novelty of the moving image. While distinct from the photographic and projection technologies that would later define cinema, Carmontelle's transparencies represent a crucial step in the history of visual media, exploring the potential of sequential images, light, and narrative to create dynamic visual experiences. They demonstrate his fascination with light, illusion, and the representation of time and space – themes that connect his work across different media, from garden design to theatre and painting. This invention highlights his position not just as an artist reflecting his time, but as an innovator looking towards the future of entertainment and visual culture.

Carmontelle and His Contemporaries

Carmontelle operated within a rich and dynamic artistic milieu. His long career placed him alongside several generations of artists, writers, and thinkers. His portraits provide a direct link to many key figures, most notably the Mozart family. His relationship with his patrons, the Dukes of Orléans, connected him to the highest levels of French society and political life.

In the realm of painting, he worked during the flourishing of the Rococo, exemplified by François Boucher and Jean-Honoré Fragonard, whose sensuous and lighthearted styles differed significantly from Carmontelle's more restrained and documentary approach to portraiture. Yet, like them, he catered to an aristocratic clientele seeking elegance and charm. His detailed realism shares some affinity with the genre scenes of Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin or the moralizing dramas of Jean-Baptiste Greuze, though Carmontelle rarely ventured into narrative painting beyond his transparencies. His profile portraits find parallels in the work of silhouette artists and medallists, but his use of color and full-length format gave them greater substance. Compared to the penetrating psychological depth achieved by pastelists like Maurice Quentin de La Tour or Jean-Étienne Liotard, Carmontelle's portraits often appear more focused on social presentation and external likeness.

His work in garden design placed him in dialogue with the international trend of the picturesque, influenced by English designers like Lancelot "Capability" Brown and William Kent, although Carmontelle's Parc Monceau, with its dense collection of follies, represented a more theatrical, French interpretation of the style. He shared an interest in architectural elements within landscapes with contemporaries like the painter Hubert Robert, famed for his romantic depictions of ruins, and architects like Claude-Nicolas Ledoux, who also designed imaginative follies.

In theatre, his proverbes dramatiques offered a distinct alternative to the established genres. They shared the focus on witty dialogue found in the comedies of Pierre de Marivaux, but were generally shorter and less complex. They existed alongside the more politically charged plays of Beaumarchais (like The Barber of Seville and The Marriage of Figaro) and the grand Neoclassical tragedies that still held sway at the Comédie-Française. Carmontelle's contribution was unique in its intimate scale and focus on illustrating social maxims through lighthearted comedy.

His multifaceted career also aligns him with the spirit of the Enlightenment, embodied by figures like Denis Diderot, editor of the Encyclopédie, who championed observation, reason, and the interconnectedness of arts and sciences. Carmontelle, through his diverse activities – from engineering and invention to painting and playwriting – exemplified the era's ideal of the versatile, engaged individual. As Neoclassicism began to rise in the later part of his career, championed by Jacques-Louis David, Carmontelle's style remained largely rooted in the aesthetics of the mid-18th century, providing a valuable counterpoint to the sterner, more heroic art that would dominate the Revolutionary and Napoleonic periods.

Artistic Style and Characteristics

Carmontelle's artistic style is characterized by its versatility, precision, and charm. In his most recognized works, the profile portraits, his approach was consistent: a clear, linear rendering of the subject's silhouette, usually full-length, filled with delicate watercolor washes and heightened with opaque gouache for details of fabric and texture. The emphasis was on accurate likeness and the careful depiction of costume and bearing, capturing the elegance and social codes of his sitters. While lacking the overt emotionalism of some Rococo art or the psychological probing of later portraitists, his works possess a clarity and immediacy that make them invaluable historical documents.

His landscape work, seen in the design for Parc Monceau and in his transparencies, reveals a different facet of his sensibility. Here, he embraced the picturesque, favoring irregularity, variety, and the evocation of mood and atmosphere. His transparencies, in particular, show a mastery of light and color to create effects of depth, distance, and changing conditions. The continuous scroll format required a narrative approach to landscape, linking scenes together smoothly and imaginatively.

Across his diverse output, a unifying thread is his keen observation of the world around him, whether capturing the specific features of a face, the details of fashion, the nuances of social interaction for his plays, or the potential of a landscape for imaginative transformation. His technical skill, likely honed during his early engineering training, is evident in the precision of his drawing and the ingenuity of his inventions like the transparencies.

While rooted in the aesthetics of the 18th century, Carmontelle was not merely a follower of trends but an active innovator. His development of the proverbe dramatique added a new genre to French theatre. His design for Parc Monceau was a pioneering example of the picturesque garden in France. And his transparencies explored new possibilities for visual entertainment, anticipating later developments in optical devices and moving images. His style, therefore, is best understood as a unique blend of meticulous observation, elegant execution, and inventive spirit.

Legacy and Art Historical Significance

Louis Carrogis Carmontelle's legacy is multifaceted, reflecting his diverse contributions to French culture. While he may not have achieved the same level of fame during his lifetime or immediately after as some of his more specialized contemporaries, his importance has been increasingly recognized by art historians, theatre scholars, and historians of visual culture.

As a portraitist, his vast output provides an irreplaceable visual record of French society in the decades before the Revolution. The sheer number of individuals he depicted, from the highest nobility to artists and intellectuals, offers a unique cross-section of the Ancien Régime's elite. The Musée Condé collection remains a primary resource for scholars studying this period. His distinctive profile format and watercolor technique represent a specific and recognizable contribution to 18th-century portraiture.

In landscape design, Parc Monceau stands as a key monument in the transition from formal to picturesque gardens in France. Its influence, despite later alterations, was considerable, popularizing the use of follies and the creation of varied, evocative scenes within a garden setting. Carmontelle's role in its conception solidifies his place as an important figure in the history of garden art.

His invention of the transparencies marks him as a pioneer in the prehistory of cinema. By creating moving images through painted scrolls and light, he explored concepts of visual narrative and illusion that foreshadowed later technological developments. His work in this area connects him to a longer history of optical devices and visual spectacles, highlighting the Enlightenment's fascination with science, perception, and entertainment.

In theatre, the proverbes dramatiques represent a charming and characteristic genre of 18th-century private entertainment. Carmontelle's prolific output in this form demonstrates his wit, social observation, and understanding of the intimate theatrical context of the salon.

Overall, Carmontelle embodies the spirit of the Enlightenment polymath – curious, inventive, and engaged across multiple disciplines. His career demonstrates the fluidity between art, design, science, and entertainment in the 18th century. While perhaps overshadowed by artists who focused more singularly on painting or sculpture, Carmontelle's unique combination of talents and his innovative contributions across different fields secure his significance. His work offers a window into the refined, complex, and rapidly changing world of 18th-century France, capturing its personalities, its tastes, and its burgeoning interest in new forms of expression and amusement. His rediscovery in recent decades underscores the richness and diversity of artistic practice during this pivotal era.

Conclusion

Louis Carrogis Carmontelle was a remarkable figure whose talents defied easy categorization. From his humble beginnings, he rose to become a chronicler of aristocratic life, an innovator in garden design, a popularizer of a unique theatrical genre, and a pioneer in visual entertainment. His portraits capture the faces of an era, his Parc Monceau shaped the Parisian landscape, his plays enlivened salons, and his transparencies offered glimpses into the future of moving images. As an artist, designer, writer, and inventor, Carmontelle left an indelible mark on the cultural fabric of 18th-century France, embodying the versatile genius and creative ferment of the Enlightenment. His extensive and varied body of work continues to fascinate and inform, offering rich insights into the art, society, and innovations of his time.