Louis Léopold Boilly stands as a unique and prolific figure in French art history. Spanning a remarkable career that witnessed the dramatic upheavals of the French Revolution, the rise and fall of Napoleon, the Bourbon Restoration, and the July Monarchy, Boilly became an unparalleled visual chronicler of Parisian society. Born on July 5, 1761, in La Bassée, near Lille in northern France, and passing away in Paris on January 6, 1845, his life encompassed eras of profound transformation. He was not merely a painter but also an accomplished draughtsman and an early pioneer of lithography, leaving behind an estimated 5,000 portraits and 500 genre scenes, a testament to his tireless industry and keen observation.

Unlike many of his contemporaries who focused on grand historical narratives or aristocratic portraiture, Boilly turned his meticulous gaze towards the everyday lives of the burgeoning middle class. His canvases bustle with the energy of Parisian streets, salons, cafés, and domestic interiors, capturing the nuances of social interaction, fashion, and popular pastimes with wit, precision, and an undeniable charm. He remains a vital source for understanding the social fabric and visual culture of France during a pivotal period of its history.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Boilly's artistic journey began not in the prestigious academies of Paris, but in the provincial setting of La Bassée. His father was a modest wood sculptor, providing an early exposure to craft and form. Young Louis Léopold showed a precocious talent for drawing and painting, largely developing his initial skills through self-teaching. His innate ability quickly surpassed the opportunities available in his small hometown.

Seeking broader horizons, Boilly moved to Douai around 1775, where he likely encountered the works of local artists and began to refine his technique. A significant step came in 1779 when he relocated to Arras. There, he gained the attention and patronage of the Bishop, which provided crucial support. It was also in Arras, or possibly shortly before, that he received more formal, albeit brief, instruction. A key figure in this period was Dominique Doncre, from whom Boilly learned the techniques of perspective and, importantly, grisaille – painting in shades of grey or neutral tones to mimic sculpture or create specific atmospheric effects. This mastery of grisaille would become a recurring feature in his work, particularly in his illusionistic paintings.

The allure of the capital, the epicenter of French art and culture, eventually drew him. In 1785, Boilly made the decisive move to Paris. He arrived not as a student seeking entry into the Royal Academy, but as an ambitious young artist already possessing considerable technical skill and a distinct artistic vision, ready to make his mark on the bustling Parisian art scene. His provincial training, focused on careful observation and precise rendering, provided a solid foundation for the career that lay ahead.

Navigating the Revolution and the Salon

Settling in Paris marked the beginning of Boilly's mature career. The city offered a vast, dynamic subject matter and a competitive art market. The primary venue for artists to gain recognition and patronage was the official Salon, the state-sponsored exhibition held regularly at the Louvre. Boilly began exhibiting at the Salon in 1791, just as the French Revolution was gaining momentum, and continued to participate until 1824.

The revolutionary period was fraught with danger, particularly for artists whose work could be interpreted politically. Boilly initially favored small, intimate scenes, sometimes with mildly suggestive or amorous themes reminiscent of Rococo masters like Jean-Honoré Fragonard, though rendered with a smoother, more precise finish. One such work, reportedly depicting lovers and perhaps deemed too frivolous or licentious by the increasingly austere revolutionary authorities (specifically the 'Société Républicaine des Arts'), brought him under scrutiny around 1794. Accusations of producing works contrary to republican morality could have severe consequences during the Reign of Terror.

To deflect criticism and demonstrate his patriotism, Boilly shrewdly shifted his subject matter. He produced works aligned with revolutionary sentiment, most notably the Triumph of Marat (1794). This painting, depicting the popular revolutionary figure Jean-Paul Marat being celebrated after his acquittal (or possibly his funeral procession), served as a public declaration of his republican sympathies. It was a calculated move that likely saved his career, if not his life, allowing him to continue working through the turbulent political shifts. This period highlights Boilly's adaptability and his ability to navigate the treacherous currents of revolutionary politics, a skill essential for survival and success. His contemporary, Jacques-Louis David, dominated the era with monumental neoclassical paintings promoting revolutionary virtues, offering a stark contrast to Boilly's more intimate focus.

The Art of Observation: Genre Scenes

While Boilly produced patriotic works when necessary, his true passion and enduring legacy lie in his genre scenes – detailed, often narrative depictions of everyday Parisian life. He possessed an extraordinary eye for the minutiae of social behavior, fashion, and environment. His canvases offer a vibrant panorama of the era, capturing the activities of the middle and upper-middle classes in their homes, studios, public spaces, and streets.

Boilly's genre paintings often feature crowded compositions, skillfully managing numerous figures engaged in various activities. Works like The Arrival of a Mail-coach in the Courtyard of the Messageries (1803), which won him a gold medal at the Salon of 1804, exemplify his ability to orchestrate complex scenes teeming with life and individual character studies. He depicted public spectacles, street performers, market scenes, the interiors of cafés, billiard rooms (The Billiard Game, c. 1807), and intimate family gatherings.

His approach combined the detailed realism reminiscent of 17th-century Dutch masters like Jan Steen or Gerard ter Borch with a distinctly French sensibility. There is often a gentle humor or light satire in his observations of human foibles and social interactions. He captured the changing fashions, the introduction of new technologies (like gas lighting, implicitly shown in some later street scenes), and the shifting social dynamics of post-revolutionary France. Unlike Jean-Baptiste Greuze, whose earlier genre scenes often carried heavy moralizing messages, Boilly's work tends to be more observational and less didactic, presenting a lively tableau for the viewer's enjoyment and contemplation.

Master of Portraiture

Alongside his genre scenes, Boilly was an exceptionally prolific and sought-after portraitist. He is estimated to have painted thousands of portraits, catering to a broad clientele primarily from the middle class – merchants, professionals, fellow artists, and their families. His success in this field was partly due to his remarkable speed and efficiency, combined with his ability to capture a convincing likeness.

Boilly developed a particular specialty: small-format portraits, often head-and-shoulders or bust-length, painted with smooth precision on canvas or panel, sometimes even on ivory. He famously claimed he could complete such a portrait in just two hours. This rapid production method allowed him to offer portraits at relatively affordable prices, making them accessible to a wider audience than the grand portraits commissioned by the aristocracy from artists like Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun or François Gérard. These small works, sometimes referred to as "portraits à deux heures" (two-hour portraits), became immensely popular.

Despite the speed of execution, Boilly's portraits rarely feel superficial. He possessed a keen ability to capture not just the physical features but also a sense of the sitter's personality and psychological presence. His subjects often meet the viewer's gaze directly, engaging them with a sense of immediacy. The Portrait of Monsieur Jacque (date unknown), noted for its subtle smile and engaging eyes, demonstrates his skill in conveying individuality. While lacking the heroic grandeur of David's portraits or the refined elegance of Ingres's later work, Boilly's portraits offer an intimate and relatable glimpse into the faces of his time.

Innovation in Print: Lithography and Trompe-l'œil

Boilly was not only a master of the brush but also an innovator in graphic arts and illusionistic techniques. He was among the very first artists in France to embrace lithography, a printmaking process invented in Germany by Alois Senefelder in the late 1790s. Lithography allowed for greater freedom and subtlety in drawing directly onto the printing stone, facilitating mass production of images.

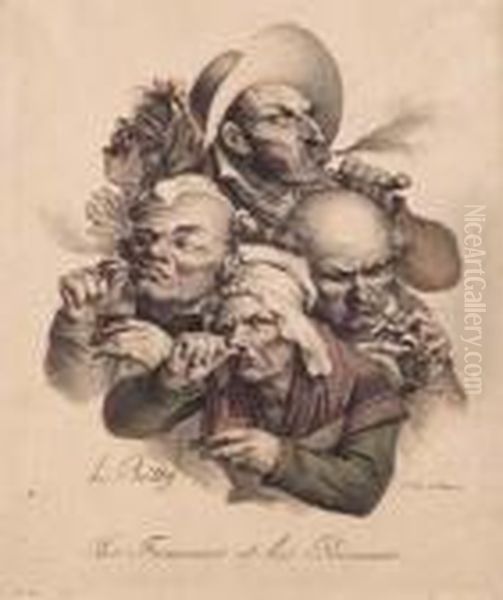

Boilly quickly recognized the potential of this new medium, both artistically and commercially. Between 1823 and 1828, he produced a famous series of lithographs titled Recueil de Grimaces (Collection of Grimaces). This set of nearly 100 prints depicted exaggerated facial expressions and character types, showcasing his sharp wit and skill in capturing fleeting emotions and physiognomic variety. These prints were highly popular and contributed significantly to his income and reputation. His work in lithography paved the way for later masters of the medium, such as Honoré Daumier, who would use it extensively for social and political satire.

Furthermore, Boilly was a master of trompe-l'œil (literally, "deceive the eye") painting. This technique uses realistic imagery to create optical illusions, making depicted objects appear three-dimensional and tangible. Boilly applied this skill with remarkable finesse, often depicting arrangements of everyday objects – letters, drawings, coins, spectacles – seemingly tacked onto a wooden board or scattered across a tabletop, rendered with such precision that viewers might be tempted to touch them. Works like Trompe-l'œil with Playing Cards, Letters, and Coins (c. 1800-1805) demonstrate his virtuosity in this genre, playing with perception and reality in a manner that delighted his audience. His early training in perspective and grisaille under Doncre undoubtedly contributed to his success in this demanding technique.

Key Works and Themes

Boilly's vast oeuvre includes several standout works that encapsulate his style, themes, and historical context.

The Triumph of Marat (1794): As mentioned, this work was crucial for navigating the Terror. It depicts the revolutionary figure Marat being carried aloft by an adoring crowd, showcasing Boilly's ability to handle large group scenes and respond to political demands. It contrasts sharply with David's stark and iconic Death of Marat.

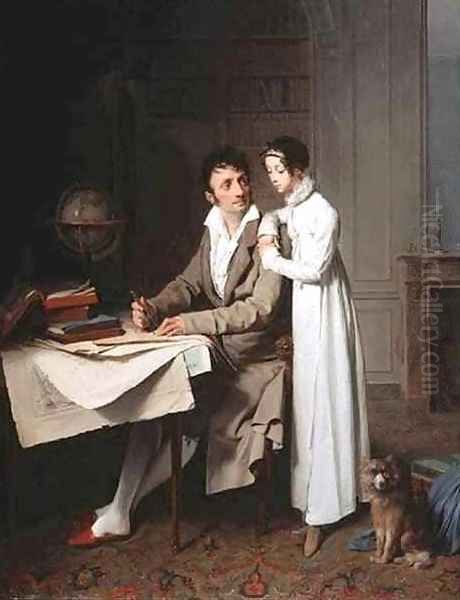

Gathering of Artists in Isabey's Studio (1798): This celebrated group portrait is a masterpiece of social observation within the art world. It depicts numerous prominent artists and figures of the Directory period assembled in the studio of fellow painter Jean-Baptiste Isabey. Boilly includes himself in the composition, looking out at the viewer. The painting is remarkable for its detailed rendering of individual likenesses and the lively, informal atmosphere it captures, offering a unique glimpse into the artistic community of the time. Figures identified include painters like François Gérard, Carle Vernet, and sculptors like Claude Dejoux.

The Arrival of a Mail-coach in the Courtyard of the Messageries (1803): This large, bustling scene captures the chaotic energy of a public transport hub in Paris. Boilly masterfully orchestrates dozens of figures – travelers, workers, onlookers, animals – creating a vivid snapshot of urban life. Its success at the 1804 Salon cemented his reputation as a leading genre painter.

The Checkers Game (Le Jeu de Dames) (c. 1803) / The Billiard Game (c. 1807): These paintings depict popular pastimes in interior settings, likely cafés or private clubs. They showcase Boilly's skill in rendering textures, light effects (often artificial light), and the subtle dynamics of social interaction among the players and spectators. The compositions are carefully structured, often with a clarity influenced by Neoclassicism but focused on contemporary life.

Recueil de Grimaces (1823-1828): This series of lithographs, while not paintings, is essential to understanding Boilly's satirical vein and his pioneering role in printmaking. The exaggerated expressions explore the range of human emotion and social types with humor and keen observation.

Other notable works include numerous intimate portraits, charming scenes of family life like Les Deux Sœurs (The Two Sisters), and his technically brilliant trompe-l'œil still lifes. Across these varied works, recurring themes include the vibrancy of Parisian life, the nuances of social class, the pursuit of leisure, and the spectrum of human expression.

Artistic Circle and Contemporaries

Throughout his long career in Paris, Boilly interacted with and worked alongside many prominent figures in the French art world. His Gathering of Artists in Isabey's Studio provides direct visual evidence of his connections.

Jean-Baptiste Isabey (1767-1855): A highly successful miniaturist and portrait painter, Isabey was a key figure in Boilly's circle. Boilly's famous group portrait is set in Isabey's studio, indicating a close professional relationship, possibly even mentorship or collaboration early on.

Dominique Doncre (1743-1820): Boilly's teacher in Arras, crucial for his technical grounding in perspective and grisaille.

Jean-Antoine Houdon (1741-1828): The preeminent sculptor of the era. Boilly painted Houdon Modeling the Bust of Laplace in his Studio (1804), demonstrating his access to and respect for fellow leading artists.

Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825): The dominant figure of Neoclassicism and the Revolution. While their styles and primary subjects differed greatly, Boilly operated in the artistic environment shaped by David's influence and political power.

Jean-Baptiste Greuze (1725-1805): An earlier master of sentimental genre scenes. Boilly's work can be seen as a less moralizing, more observational continuation of the interest in everyday life that Greuze popularized.

Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842): A celebrated portraitist, particularly favored by the aristocracy before the Revolution. Her elegant style contrasts with Boilly's often more direct and middle-class focus.

Pierre-Paul Prud'hon (1758-1823): Known for his graceful, allegorical, and portrait paintings with a soft, sfumato effect, offering another stylistic counterpoint to Boilly's precision.

François Gérard (1770-1837): A pupil of David who became a leading portraitist of the Napoleonic elite and the Restoration monarchy.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867): A younger contemporary and another major figure of Neoclassicism, renowned for his linear precision and idealized forms, particularly in portraiture and historical scenes.

Théodore Géricault (1791-1824) & Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863): Leaders of the emerging Romantic movement, whose dramatic subjects and painterly techniques marked a significant departure from the styles prevalent during Boilly's formative years.

Honoré Daumier (1808-1879): A later master lithographer and social satirist, whose work owes a debt to pioneers like Boilly in establishing lithography as a powerful medium for commentary.

Boilly's network also included patrons like Calvet de la Planche and Madame Deslales, who provided crucial support, especially early in his Parisian career. He successfully navigated this complex artistic landscape, maintaining his unique focus while adapting to changing tastes and political regimes.

Later Years and Legacy

Boilly remained remarkably productive throughout his long life. He continued to paint and exhibit regularly well into the 19th century. His dedication and skill were officially recognized in 1833 when, at the age of 72, he was awarded the Cross of the Legion of Honour, a prestigious acknowledgment of his contribution to French art.

He witnessed the continued evolution of French art, seeing the rise of Romanticism and the beginnings of Realism. While his own style remained largely consistent – characterized by meticulous detail, smooth finish, and careful composition – his subject matter continued to reflect the changing times. His later works provide valuable documentation of Parisian life during the Restoration and the July Monarchy.

Boilly passed away in Paris in 1845 at the venerable age of 83. He left behind a legacy not only in his vast body of work but also through his family; his son, Julien Léopold Boilly (1796–1874), also became a painter and printmaker, continuing the artistic tradition. Another son, Alphonse Léopold Boilly (1801–1867), was a noted engraver.

Louis Léopold Boilly's influence extends beyond his immediate circle. His detailed genre scenes provided a model for later 19th-century painters interested in depicting contemporary urban life. His pioneering work in lithography contributed to the flourishing of printmaking as both an art form and a medium for popular dissemination of images and social commentary. Most importantly, his paintings and prints offer an unparalleled visual archive of a transformative period in French history, capturing the faces, fashions, and daily activities of Parisians with an intimacy and breadth few other artists achieved.

Conclusion: An Enduring Window onto Paris

Louis Léopold Boilly occupies a significant and distinct place in the history of French art. He was not a revolutionary innovator in the mold of David or Delacroix, nor did he pursue the idealized beauty of Ingres. Instead, he carved out a unique niche as the consummate observer and chronicler of his time. His meticulous technique, combined with a keen eye for social detail and a subtle wit, allowed him to capture the pulse of Parisian life across nearly six decades of dramatic change.

From his charmingly rendered portraits capturing the individuality of the burgeoning middle class to his bustling genre scenes documenting public and private life, Boilly created a vast and invaluable visual record. His mastery of trompe-l'œil demonstrated his technical virtuosity, while his early adoption and skillful use of lithography highlighted his engagement with new artistic possibilities. Surviving the political turmoil of the Revolution and adapting to subsequent regimes, he maintained a prolific output that continues to fascinate historians and art lovers alike. Boilly's work remains an enduring, detailed, and engaging window onto the society, culture, and people of Paris during one of its most dynamic and formative periods.