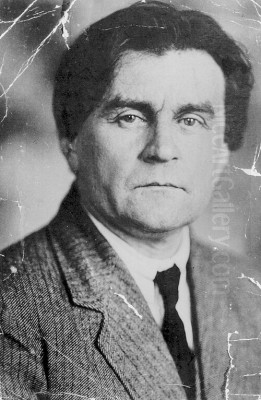

Kazimir Severinovich Malevich stands as a titan of 20th-century art, a revolutionary figure whose radical ideas and groundbreaking works fundamentally altered the course of modernism. Born near Kyiv in the Russian Empire (now Ukraine) in 1879 to parents of Polish descent, he rose from provincial beginnings to become the founder of Suprematism, one of the earliest and most uncompromising movements of abstract art. His quest for an art of pure feeling, liberated from the depiction of the objective world, culminated in iconic works like the Black Square, a painting that has become synonymous with the dawn of non-representational art. This exploration delves into the life, artistic evolution, theoretical contributions, and enduring legacy of this pivotal artist.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Malevich's early life was marked by movement and a growing awareness of art. His father managed sugar refineries, and the family relocated frequently across Ukraine. This exposure to rural life and peasant crafts, particularly the geometric patterns and bold colors of folk art, arguably planted seeds for his later abstract vocabulary. Though his parents were ethnically Polish and Roman Catholic, Malevich's own spiritual and philosophical inclinations would later draw from a wider, more mystical pool of ideas.

His formal artistic training was intermittent initially. He studied drawing in Kyiv and later attended the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture. His early works from the first decade of the 20th century show an artist absorbing the major European trends of the time. He moved through phases of Realism, Impressionism (showing affinities with the work of Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro), and Post-Impressionism, clearly impacted by the structural concerns of Paul Cézanne and the symbolic color of Paul Gauguin.

A crucial phase was his engagement with the burgeoning Russian avant-garde. He participated in key exhibitions, including those of the Moscow Association of Artists and the provocative Jack of Diamonds group, alongside figures like Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova. These artists were actively synthesizing Western European innovations with Russian traditions, leading Malevich towards Neo-Primitivism, drawing inspiration from Russian icons and folk prints (lubki).

The influence of Cubism, pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, and Italian Futurism, championed by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and Umberto Boccioni, proved transformative. Malevich assimilated these styles, forging his own powerful synthesis known as Cubo-Futurism. Works from this period, such as The Knife Grinder (Principle of Glittering) (c. 1913), demonstrate a dynamic fragmentation of form and the depiction of motion characteristic of these influences, yet with a distinctly robust, almost sculptural quality. He also explored what he termed "Alogism," creating deliberately illogical combinations of objects and text.

The Genesis of Suprematism

The years 1913-1915 were a period of intense experimentation that led Malevich to a radical break. A significant catalyst was his work designing sets and costumes for the avant-garde Futurist opera Victory Over the Sun (1913), with music by Mikhail Matyushin and a libretto by Aleksei Kruchenykh written in the experimental "zaum" (transrational) language. One of Malevich's backdrop designs featured a simple black square, an element that would soon become central to his new artistic philosophy.

This period saw Malevich push beyond the analysis of objects inherent in Cubism and the dynamism of Futurism towards complete abstraction. He sought an art that conveyed pure feeling or sensation, unburdened by the need to represent the visible world. He termed this new direction "Suprematism," signifying the supremacy of pure artistic feeling over the depiction of objects.

The public debut of Suprematism occurred at "The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0,10," held in Petrograd (now St. Petersburg) in December 1915. Malevich exhibited a stunning group of 39 abstract works. Hung prominently in the corner of the room, in the position traditionally reserved for a religious icon in Russian Orthodox homes, was the Black Square (or Black Suprematist Square). This simple composition – a black square painted on a white canvas – was a bombshell. It represented a point of absolute zero in painting, a rejection of representation and a bold declaration of a new artistic reality. Alongside it were other fundamental Suprematist forms, like Black Circle and Black Cross, as well as compositions featuring colored rectangles.

Suprematist Theory and Practice

Malevich was not only a painter but also a prolific theorist. He accompanied the unveiling of Suprematism with writings that articulated its philosophical underpinnings. In his 1915 manifesto, From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism in Art, he declared the need to liberate art from the "ballast of the objective world." For Malevich, the visual phenomena of the objective world were, in themselves, meaningless; the significant thing was feeling, as such, quite apart from the environment in which it was called forth.

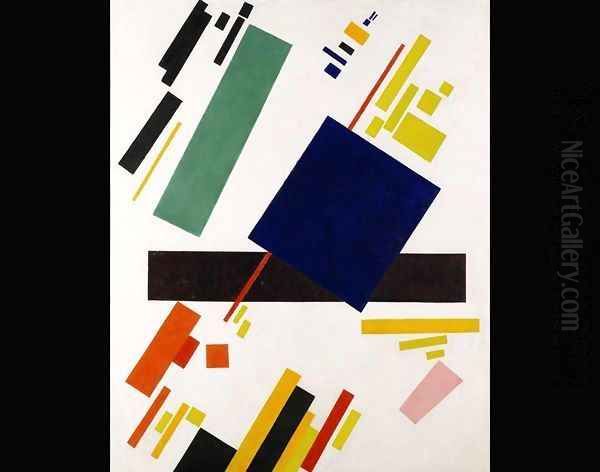

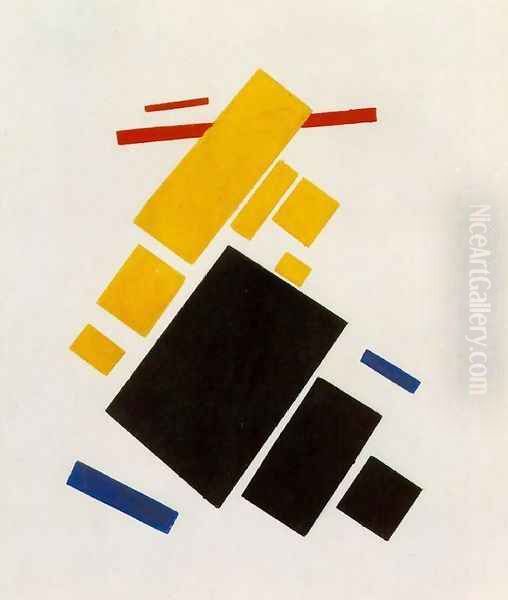

Suprematism aimed to access a higher, non-objective reality, a "fourth dimension" beyond the three dimensions of the physical world. Basic geometric shapes – the square, circle, and cross – became the fundamental elements of this new visual language. Color was used for its inherent emotional and spatial properties, often limited initially to black, white, red, and later expanding to include other hues. The white background of his canvases was not merely passive space but represented the infinite, the void of sensation in which his forms floated.

Malevich's Suprematist work evolved. Early compositions featured static, stable arrangements of one or a few basic shapes. Later works, often termed "Dynamic Suprematism," introduced diagonal axes, overlapping shapes, and a greater sense of movement and spatial complexity, as seen in pieces like Suprematist Composition: Airplane Flying (1915). He explored the subtle relationships between form and color, pushing towards ultimate purity.

This quest reached its zenith around 1918 with his White on White series, most famously Suprematist Composition: White on White. Here, a white square is painted tilted against a white background, differentiated only by subtle shifts in tone and texture. It represented an attempt to depict the dissolution of form into pure, infinite space, the very essence of non-objectivity.

Teaching, UNOVIS, and Spreading the Word

Malevich was deeply committed to disseminating his ideas and fostering a new generation of artists. In 1919, he was invited by Marc Chagall to teach at the People's Art School in Vitebsk (present-day Belarus). Chagall, however, represented a more figurative and poetic strand of modernism, and ideological clashes soon led to Chagall's departure. Malevich transformed the school into a laboratory for Suprematism.

He gathered around him a group of dedicated students and followers, forming the collective UNOVIS (Utverditeli Novogo Iskusstva – Champions of the New Art). Key members included El Lissitzky, Ilya Chashnik, Nikolai Suetin, and Lazar Khidekel. UNOVIS aimed to integrate Suprematist principles into all aspects of life, moving beyond easel painting into design, typography, architecture, and propaganda. They created posters, designed textiles and ceramics, and envisioned utopian Suprematist architecture through Malevich's "Arkhitektons" and "Planits" – plaster models of abstract architectural forms.

In 1922, Malevich moved to Petrograd (renamed Leningrad in 1924), where he continued his theoretical work and teaching at GINKhUK (State Institute of Artistic Culture). He developed complex charts and diagrams analyzing the evolution of art and exploring concepts like the "additional element" in painting, attempting to create a scientific basis for his artistic theories.

Complex Relationships: Contemporaries and Collaborators

The Russian avant-garde was a crucible of intense debate and shifting alliances, and Malevich's relationships with his contemporaries were often complex and fraught with rivalry. His interaction with Wassily Kandinsky, another pioneer of abstraction, highlights differing paths. While both sought spirituality in art, Kandinsky's abstraction remained rooted in expressive color and form, often retaining symbolic or emotional connotations, whereas Malevich pursued a more radical, geometric purity. They were aware of each other's work and exhibited internationally, but represented distinct poles within non-objective art.

A more direct rivalry existed with Vladimir Tatlin, the founder of Constructivism. While Suprematism focused on pure art and spiritual feeling, Constructivism emphasized the artist as a technician, using industrial materials and functional design to serve the new socialist society. Tatlin's famous project for the Monument to the Third International (1919-20) epitomized this utilitarian ideal. Legend has it that Malevich and Tatlin came to blows or had a fierce argument at the "0,10" exhibition, symbolizing the deep ideological divide between their movements.

Alexander Rodchenko, another leading Constructivist, was initially influenced by Malevich's abstraction but later rejected easel painting as bourgeois, focusing on photography and design. Liubov Popova and Alexandra Exter were other prominent women artists of the avant-garde who navigated the currents of Cubo-Futurism, Suprematism, and Constructivism, developing their own unique contributions.

El Lissitzky stands out as a crucial bridge figure. Initially a devoted follower of Malevich at Vitebsk, Lissitzky developed his own concept called "Proun" (Project for the Affirmation of the New), which synthesized Suprematist geometry with architectural concerns. Lissitzky's work and travels were instrumental in transmitting Russian avant-garde ideas, including Suprematism, to Western Europe, influencing movements like De Stijl (Theo van Doesburg, Piet Mondrian) and the Bauhaus. Other artists associated with Malevich or Suprematism included Ivan Kliun, Olga Rozanova, and Nadezhda Udaltsova.

Later Years, Shifting Styles, and Political Pressure

The revolutionary fervor that had initially supported artistic experimentation in Russia began to wane by the mid-1920s. With the consolidation of power under Joseph Stalin, the Soviet state increasingly demanded art that was easily understandable and served propagandistic purposes. Socialist Realism became the officially sanctioned style, while avant-garde art was condemned as "formalist," bourgeois, and decadent.

This changing climate created immense difficulties for Malevich. In 1927, he was allowed to travel abroad for exhibitions of his work in Warsaw and Berlin. This trip proved crucial, as he left behind a significant number of paintings and theoretical writings when he was abruptly recalled to the Soviet Union. These works, eventually acquired by institutions like the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, ensured the survival and later study of his Suprematist legacy in the West.

Upon his return, Malevich faced increasing suspicion and hostility from the authorities. He was arrested in 1930 and interrogated, accused of Polish espionage (likely due to his Polish heritage and recent trip). Although released after a few months, his position became precarious. He lost his teaching posts, and his opportunities to exhibit dwindled.

Under this pressure, Malevich largely abandoned abstract art in his final years. He returned to figurative painting, but his late works are far from a simple reversion to his earlier styles. He painted portraits and scenes of peasant life, often depicting figures with blank, featureless faces or simplified, geometric bodies. Works like the Peasants series and Red Cavalry Riding (c. 1932) retain a monumental quality and symbolic resonance, often interpreted as a coded commentary on the collectivization of agriculture and the plight of the peasantry, filtered through a Suprematist sensibility of form and color. Some see this late phase as a forced compromise, others as a final, complex synthesis of his artistic journey.

Kazimir Malevich died of cancer in Leningrad in 1935. In a final testament to his artistic vision, his students designed a Suprematist-inspired coffin for him, and his ashes were buried near Nemchinovka, marked by a simple black square – a monument later destroyed during World War II but recreated in recent years.

Anecdotes, Controversies, and Interpretations

Malevich's life and work are rich with intriguing details and ongoing debates. His complex identity – born in Ukraine to Polish parents, working within the Russian/Soviet cultural sphere – reflects the shifting borders and identities of the era. His early Catholic upbringing contrasted with his later embrace of more esoteric, mystical, and philosophical ideas that informed Suprematism's spiritual aspirations.

The Black Square remains his most debated work. Was it an act of artistic nihilism, a spiritual icon for a new age, the "zero point" of painting, or something else entirely? The fact that Malevich painted multiple versions (at least four are known) adds to the complexity. Scientific analysis has revealed earlier, colorful Cubo-Futurist compositions hidden beneath the black paint of the original 1915 version, prompting speculation about its creation – was it a sudden inspiration or a deliberate obliteration of his past?

His relationships with contemporaries like Chagall, Kandinsky, and Tatlin were marked by both collaboration and intense rivalry, reflecting the high stakes and passionate convictions of the avant-garde era. His arrest and the political suppression of his work highlight the dangers faced by artists under totalitarian regimes.

Even after his death, controversy continued. The works Malevich left in Germany in 1927 became the subject of complex legal battles over ownership and restitution involving his heirs and major museums, particularly the Stedelijk Museum, which holds the largest collection of his work outside of Russia. The interpretation of his late figurative work also remains contested – was it a capitulation to state pressure or a subtle form of artistic resistance?

Enduring Influence and Legacy

Despite the suppression of his work in the Soviet Union for decades, Malevich's influence on the course of 20th and 21st-century art has been profound and enduring. He is universally recognized as a pioneer of geometric abstraction and a key figure in the transition to non-representational art.

Suprematism's radical reduction of form and its emphasis on pure feeling had an immediate impact on the Russian avant-garde, particularly on Constructivism (even in opposition) and on artists like Lissitzky who carried its principles abroad. Its ideas resonated with the geometric abstraction of De Stijl in the Netherlands and influenced the curriculum and aesthetics of the Bauhaus in Germany, largely through the efforts of Lissitzky and the publication of Malevich's theoretical text The Non-Objective World as a Bauhaus book in 1927.

After World War II, as abstract art gained prominence globally, Malevich's work was rediscovered and celebrated in the West. His uncompromising abstraction and spiritual aspirations found echoes in the work of Abstract Expressionists like Barnett Newman, whose "zip" paintings explore the void and the sublime, and Mark Rothko, whose floating fields of color evoke profound emotional and spiritual states.

Malevich's legacy is perhaps most clearly felt in the development of Minimalism in the 1960s. Artists like Donald Judd, Frank Stella, and particularly Ad Reinhardt, with his own "black paintings," looked back to Malevich's reductionism, his use of basic geometric forms, and his exploration of art's fundamental essence. His theoretical writings continue to be studied by artists, critics, and historians grappling with the nature and purpose of abstract art.

Global Collections and Market Recognition

Today, Kazimir Malevich's works are held in major museum collections around the world, testifying to his established importance in art history. The State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow and the State Russian Museum in St. Petersburg hold significant collections within Russia. As mentioned, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam boasts the largest and most comprehensive collection outside of Russia, thanks to the works left behind in 1927.

Other key institutions housing important Malevich works include the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Centre Pompidou in Paris, and the State Museum of Contemporary Art in Thessaloniki, Greece (Costakis collection).

His stature is also reflected in the art market. His paintings, particularly rare Suprematist compositions, command exceptionally high prices at auction. Suprematist Composition (1916) set a record for Russian art when it sold for $60 million at Sotheby's in 2008; the same painting later sold for $85.8 million at Christie's in 2018, reaffirming its status as one of his most valuable works. Even works on paper, like a Landscape from his early period, have achieved record prices, demonstrating the sustained demand for his art across different periods and media.

Scholarly Perspectives and Historical Assessment

Kazimir Malevich continues to be a subject of intense scholarly interest. A vast body of literature explores his life, his artistic evolution from Impressionism to Suprematism and back to figuration, his complex theoretical writings, and his relationships with contemporaries. Key publications include catalogues raisonnés, collections of his letters and theoretical texts (such as those edited by Troels Andersen, Andrei Nakov, Irina Varkina, and Tatiana Mikhienko), and critical biographies.

Research methodologies vary widely, encompassing formal analysis, iconographic studies, philosophical interpretations of his theories, and historical contextualization within the turbulent socio-political landscape of revolutionary Russia and the early Soviet Union. Scholars like Andrei Nakov have delved deep into the nuances of his theory and its connections to European philosophy and even Polish religious art, while others like Rainer Crone and David Moos have explored potential links between his late work and contemporary scientific ideas like quantum physics.

The assessment of Malevich's historical significance has evolved. Marginalized and officially condemned in his homeland for much of the Soviet period, his reputation was largely kept alive in the West, beginning with Alfred H. Barr Jr.'s inclusion of his work at MoMA in the 1930s and gaining momentum from the 1950s onwards. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, there has been a resurgence of interest and research within Russia as well. He is now unequivocally recognized as a central figure of the global avant-garde, whose radical vision pushed the boundaries of what art could be. Ongoing research continues to uncover new facets of his work and thought, ensuring his continued relevance.

Conclusion: A Visionary of the Absolute

Kazimir Malevich was more than just a painter; he was a visionary theorist, an influential teacher, and a fearless innovator who dared to strip art down to its essential elements. His creation of Suprematism marked a definitive break with centuries of representational tradition, proposing an art of pure form and feeling intended to resonate on a spiritual, almost cosmic level. The Black Square, in its stark simplicity, remains one of the most potent and challenging images in modern art history – an icon of the abstract revolution.

Through his paintings, his extensive writings, and his pedagogical activities, Malevich sought to define a new role for art in the modern world, one liberated from utility and imitation, focused instead on accessing fundamental truths and sensations. Though his career was ultimately constrained by political forces, his ideas and works survived to inspire generations of artists across the globe. Kazimir Malevich's legacy is that of a true architect of modernism, an artist who irrevocably changed the way we see and think about art, opening the door to the infinite possibilities of the non-objective world.