William Edward Frost (1810-1877) stands as a notable figure within the landscape of British Victorian art. Born in Wandsworth, near London, in September 1810, Frost carved a distinct niche for himself, becoming particularly renowned for his delicate and idealized depictions of the female nude, often situated within mythological or literary contexts. Operating within the influential framework of the Royal Academy, he achieved considerable success during his lifetime, though his style eventually fell somewhat out of favour compared to newer artistic movements. His career bridges the gap between early 19th-century traditions and the high Victorian era, offering insight into the tastes and artistic currents of the time.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Frost's inclination towards art manifested early in his life. Recognizing this burgeoning talent, his father actively encouraged his pursuits, arranging for him to receive initial instruction in drawing. A pivotal moment occurred around 1825 when, through an introduction facilitated by his father, the young Frost met the established artist William Etty. This connection proved significant, as Etty was arguably the most prominent British painter specializing in the nude form during that period.

Following this introduction, Frost's formal training began in earnest. He spent time, from approximately 1826 to 1828, studying at the well-regarded drawing school run by Henry Sass in Bloomsbury. Sass's academy was a preparatory school for many aspiring artists aiming for the Royal Academy Schools. Frost also gained valuable experience at the British Institution's school in Pall Mall, where he reportedly spent three summers, further honing his skills, likely benefiting again from Etty's connections or recommendations.

In 1829, Frost achieved a significant milestone by gaining admission as a student to the prestigious Royal Academy Schools. Contemporary accounts suggest that while perhaps not possessing innate genius in design or composition, Frost compensated with remarkable diligence and application. His hard work paid off, as he reportedly secured first place medals in all the schools within the Academy system he attended, demonstrating a mastery of the technical skills valued by the institution.

From Portraiture to Poetic Themes

Like many aspiring artists of his generation, Frost initially supported himself through portraiture. For over a decade, he dedicated considerable effort to this genre, reportedly completing more than 300 portraits. This practice undoubtedly refined his skills in capturing likenesses and handling paint, providing a steady income stream while he developed his artistic voice.

However, Frost's true artistic inclinations lay elsewhere. Influenced perhaps by his mentor William Etty, and certainly by the prevailing Romantic and Neoclassical tastes for historical and literary subjects, Frost began to shift his focus. He turned increasingly towards mythological narratives, allegorical scenes, and subjects drawn from classic English poetry, particularly the works of Edmund Spenser and John Milton. This transition allowed him to explore themes of beauty, grace, and the idealized human form, moving away from the specific demands of commissioned portraiture.

This shift also led him to embrace the subject matter for which he would become best known: the female nude. In Victorian Britain, the depiction of nudity was a sensitive issue, often requiring justification through classical or literary precedent. Frost, following in Etty's footsteps, specialized in presenting the nude within these acceptable frameworks, creating images that emphasized idealized beauty and grace rather than overt sensuality. He became one of the few British artists of his generation to consistently focus on this subject.

Signature Style and Technique

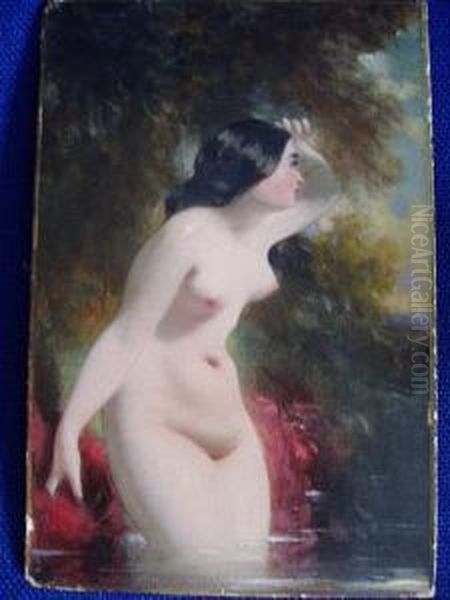

William Edward Frost developed a distinctive artistic style characterized by its refinement, elegance, and meticulous finish. His approach differed somewhat from that of his mentor, William Etty, whose nudes often possessed a more robust, fleshy quality and a richer, more painterly application of pigment. Frost's figures, by contrast, tend towards a smoother, more idealized and porcelain-like finish, reflecting perhaps a lingering Neoclassical influence combined with Victorian sensibilities.

His compositions are often described as graceful and charming, emphasizing delicate lines and harmonious arrangements. The execution is typically highly polished, with careful attention paid to detail and a smooth surface that minimizes visible brushwork. This emphasis on finish was highly valued within the Academic tradition. While praised for its "pure aesthetics" and "refined execution," his work was sometimes criticized, even during his lifetime, for a perceived lack of originality or "invention" in design. He excelled in execution rather than groundbreaking composition.

Frost often worked on a relatively modest scale, suitable for the domestic interiors of the collectors who favoured his work. His colour palettes are typically harmonious and restrained, contributing to the overall sense of delicacy and poetic sentiment that pervades his mythological and literary scenes. He became particularly associated with the subgenre of fairy painting, popular in the Victorian era, depicting nymphs, sprites, and other ethereal beings derived from mythology and literature. Artists like Richard Dadd and Daniel Maclise also explored this realm, though Frost's approach remained focused on classical grace.

Recognition, Honours, and Major Works

Frost's dedication and skill brought him significant recognition within the established art world. A major early triumph came in 1839 when his painting Prometheus Bound by Force and Strength was awarded the prestigious Gold Medal of the Royal Academy. This award marked him as a history painter of considerable promise and significantly raised his profile.

Further success followed in 1843 at the competition held to select artists to create frescoes for the new Houses of Parliament at Westminster Hall. Frost submitted a cartoon (a full-scale preparatory drawing) titled Una Alarmed (or Una Surprised by Fauns and Satyrs), based on a scene from Edmund Spenser's epic poem The Faerie Queene. His entry secured a third-place prize of £100, a notable achievement in a competition featuring prominent artists like Daniel Maclise and George Frederic Watts. This success further cemented his reputation for handling complex literary and allegorical themes.

His growing stature led to his election as an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1846. This was a crucial step towards full membership and indicated the high regard in which his peers held him. Around this time, his work also attracted royal attention. Queen Victoria herself became a patron, acquiring two significant paintings: Una (sometimes referred to as Una and the Wood Nymphs) in 1847 and Euphrosyne (depicting one of the Three Graces, embodying mirth and joy) in 1848. The Queen reportedly paid a substantial sum, possibly £420, for these works, demonstrating the appeal of Frost's graceful style to the highest echelons of society.

Other notable works from this period include The Disarming of Cupid (exhibited 1850) and various depictions of nymphs, sirens, and scenes from classical mythology. He continued to exhibit regularly at the Royal Academy throughout his career, eventually achieving the distinction of being elected a full Royal Academician (RA) in 1870.

Frost in the Victorian Art World

William Edward Frost occupied a specific position within the complex tapestry of Victorian art. He was a product of, and largely remained faithful to, the Academic system centered around the Royal Academy. His contemporaries included artists working in vastly different styles. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, founded in 1848 by figures like John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and William Holman Hunt, challenged Academic conventions with their bright colours, meticulous detail, and often morally charged subjects. Frost's work, with its idealized forms and classical leanings, stood apart from their intense realism and medievalism.

He was more closely aligned with other successful Academicians who upheld traditional values of draughtsmanship, finish, and elevated subject matter. These included figures like Sir Charles Lock Eastlake (President of the RA for a time), the immensely popular animal painter Sir Edwin Landseer, and painters of historical and genre scenes like William Powell Frith and Daniel Maclise (with whom Frost reportedly felt a sense of competitive frustration).

Later in Frost's career, the rise of Aestheticism and artists like Frederic Leighton, Edward Poynter, and Lawrence Alma-Tadema brought a different sensibility to classical subjects, often infused with a more overt sensuousness or archaeological detail than seen in Frost's work. While Frost shared their interest in the human form and mythology, his style retained a certain modesty and delicacy characteristic of the mid-Victorian period. His specialization in the nude, following Etty, placed him in a lineage distinct from the portraitists like Sir Francis Grant or narrative painters focused on modern life. He also collected prints by the visionary artist William Blake, suggesting a breadth of artistic interest beyond his own immediate style.

Later Career and Legacy

Despite his significant success and recognition, particularly during the 1840s and 1850s, Frost's influence and critical standing began to wane somewhat in the later decades of his career. Tastes in art were evolving rapidly, and his consistent adherence to his established style led some critics and collectors to perceive his later work as repetitive. The "charm" and "grace" that had initially captivated audiences perhaps began to seem less compelling compared to the innovations of younger artists or the grandeur of High Victorian classicism.

Nonetheless, he remained a respected member of the Royal Academy and continued to exhibit there until shortly before his death. He maintained a degree of popularity, particularly for his smaller cabinet pictures featuring nymphs and mythological beauties. His earlier success had provided him with financial stability.

William Edward Frost passed away on June 4, 1877, at the age of 67. His works found homes in significant public and private collections. Today, examples of his paintings can be found in institutions such as the Victoria and Albert Museum, the British Museum, the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, and regional galleries throughout the UK, as well as the Musée des Beaux-Arts d'Orléans in France.

His legacy is that of a highly skilled and successful painter within the British Academic tradition. While not considered a major innovator, he holds a significant place as William Etty's primary successor in the specialized field of the idealized female nude derived from mythological and literary sources. His work exemplifies a particular strain of Victorian taste that valued grace, refinement, and poetic sentiment, providing a delicate counterpoint to the more robust or dramatic styles of many of his contemporaries. He remains an important figure for understanding the nuances of artistic production and patronage in nineteenth-century Britain.

Conclusion

William Edward Frost navigated the Victorian art world with considerable skill, achieving prominence through dedication and a refined aesthetic. From his early training under the guidance of William Etty and Henry Sass to his successes at the Royal Academy, including the Gold Medal and election as an RA, Frost established himself as a leading painter of idealized mythological and literary subjects. His specialization in the female nude, presented with characteristic grace and delicacy, earned him royal patronage and widespread popularity, particularly during the mid-nineteenth century. While his style may have lacked the innovative drive of some contemporaries like the Pre-Raphaelites or the later classicists like Leighton or Alma-Tadema, and his influence diminished in his later years, Frost remains a key representative of Academic painting in Britain. His work offers a valuable window onto Victorian tastes, the careful negotiation of sensitive subject matter like the nude, and the enduring appeal of classical and poetic themes in nineteenth-century art.