Evelyn De Morgan stands as a significant figure in the landscape of late Victorian and Edwardian art. Born Mary Evelyn Pickering on August 30, 1855, in London, and passing away on May 2, 1919, she navigated the male-dominated art world of her time to become one of the most compelling painters associated with the second generation of the Pre-Raphaelite movement and a key exponent of British Symbolism. Her work is characterized by its rich colour, meticulous detail, profound engagement with spiritualism, mythology, and allegory, and a consistent focus on the female form as a vessel for complex ideas about struggle, transformation, and enlightenment.

Privileged Beginnings and Early Artistic Resolve

Mary Evelyn Pickering was born into an upper-middle-class family with significant intellectual and social connections. Her father, Percival Pickering QC, was a successful barrister and later Recorder of Pontefract. Her mother, Anna Maria Wilhelmina Spencer Stanhope, hailed from the aristocratic Coke family of Norfolk, descendants of the Earl of Leicester. This background afforded Evelyn opportunities for education and culture often denied to women of the era.

She was educated at home alongside her brothers, receiving a rigorous classical education that included Latin, Greek, French, German, and Italian, as well as literature, mythology, religion, and science. This broad intellectual grounding would deeply inform the thematic content of her later artistic work. From an early age, Evelyn displayed a strong inclination towards art, beginning formal drawing lessons at the age of 15.

Her passion for art was not merely a pastime; it was a driving ambition. A diary entry from this period reveals her determination: "Art is eternal, but life is short... I will not waste a moment." This sense of purpose was crucial, as pursuing a professional career in art was unconventional for a woman of her social standing. While her family initially harboured reservations, Evelyn's persistence eventually won their support.

Formal Training at the Slade School

In 1873, at the age of 17, Evelyn Pickering enrolled at the newly established Slade School of Fine Art at University College London. This was a significant step, as the Slade was one of the few institutions offering women professional artistic training comparable to that available to men. She was among the first women to study there, entering shortly after its founding.

The Slade, under the directorship of Sir Edward Poynter, emphasized rigorous classical training based on drawing from the antique and the life model. While De Morgan proved to be a talented student, winning scholarships and accolades for her draughtsmanship, including the prestigious Slade Scholarship, she was reportedly critical of the purely academic approach. She felt the curriculum lacked imaginative scope and did not fully align with her burgeoning artistic vision.

Despite her reservations about the formal curriculum, her time at the Slade provided her with essential technical skills. Her mastery of anatomy, composition, and technique is evident throughout her career. However, seeking a more spiritually and aesthetically resonant path, she did not complete her degree, leaving the Slade around 1875 to pursue her artistic development more independently.

Influences: Pre-Raphaelitism and the Italian Renaissance

Evelyn De Morgan's artistic style was profoundly shaped by two major influences: the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the art of the Italian Renaissance. Her uncle, John Roddam Spencer Stanhope, was himself a notable painter associated with the later phase of Pre-Raphaelitism. Stanhope became a crucial mentor, encouraging her talent and facilitating her connection with the wider artistic currents of the time.

Through Stanhope, and her own studies, De Morgan absorbed the Pre-Raphaelite emphasis on serious subjects, intricate detail, vibrant colour, and moral or symbolic meaning. The influence of Edward Burne-Jones, a leading figure of the second-generation Pre-Raphaelites, is particularly palpable in her work. His elongated figures, dreamlike atmospheres, and engagement with myth and legend find echoes in De Morgan's own canvases. Other artists associated with the Pre-Raphaelite circle, such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti, George Frederic Watts, and William Holman Hunt, also formed part of the artistic milieu that shaped her sensibilities.

Stanhope maintained a villa and studio near Florence, and De Morgan made several extended visits there. These trips were formative. Immersing herself in the art of the Italian Renaissance, particularly the works of Early Renaissance masters like Sandro Botticelli, had a lasting impact. The linear grace, allegorical complexity, and idealized beauty found in Quattrocento Florentine painting resonated deeply with her own artistic aims and are clearly reflected in the composition and figure types of many of her major works.

Marriage and Partnership: A Union of Art and Ideals

In 1887, at the age of 32, Evelyn Pickering married the renowned ceramic artist and designer William De Morgan. William, associated with the Arts and Crafts movement and a friend of William Morris, was considerably older but shared Evelyn's deep commitment to art and progressive social ideals. Their marriage was a partnership of minds and spirits, built on mutual respect and shared interests.

They established a home in Chelsea, a hub for artists and writers, and later moved to Florence for periods due to William's health. Their life together was marked by intellectual and artistic synergy. Both were deeply interested in spiritualism, a widespread phenomenon in late Victorian society, and they reportedly engaged in automatic writing together. This shared spiritual exploration undoubtedly fueled the mystical and allegorical themes prevalent in Evelyn's paintings.

Beyond spiritualism, they shared a commitment to social reform. Both supported the burgeoning movement for women's suffrage, prison reform, and pacifism. Evelyn's financial success as a painter often supported the couple, particularly when William's ceramics business faced difficulties. Their partnership provided a supportive environment for Evelyn to pursue her demanding career, a situation not always available to female artists of the period.

Artistic Style: Symbolism, Spirituality, and the Female Form

Evelyn De Morgan's mature style is a distinctive fusion of Pre-Raphaelite aesthetics and Symbolist concerns. While she retained the detailed naturalism and jewel-like colours associated with the Pre-Raphaelites, her primary focus shifted towards allegory and the expression of abstract concepts and spiritual states. Her work aligns strongly with the Symbolist movement, which sought to convey ideas and emotions indirectly through suggestive imagery and metaphor, rather than direct representation.

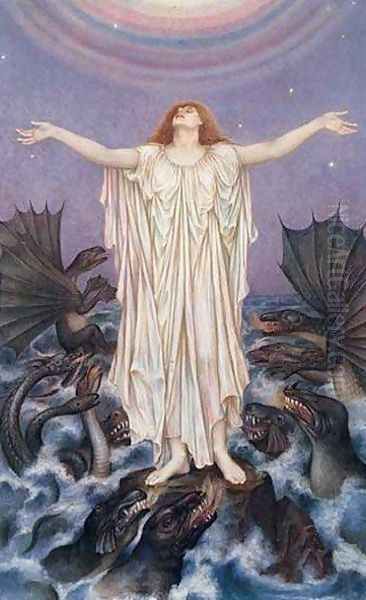

Central to her oeuvre is the female figure, often depicted as an allegorical personification of abstract concepts like hope, despair, night, dawn, or spiritual struggle. These figures are typically statuesque, draped in richly coloured, flowing robes, and placed within meticulously rendered, often symbolic landscapes or interiors. De Morgan masterfully used light and shadow, employing dramatic contrasts to signify the conflict between spiritual enlightenment and material entrapment, or hope and despair.

Her colour palette is notably vibrant and luminous, often employing iridescent effects achieved through careful layering and glazing techniques. Gold paint is frequently used, not just for decorative effect, but to symbolize divine light or spiritual transcendence. Recurring motifs include rainbows, stars, prisons, chains, wings, and flowing water, each carrying specific symbolic weight within her visual language, often related to themes of transformation, liberation, and the journey of the soul.

Themes: Feminism, Pacifism, and the Soul's Progress

De Morgan's paintings are rich with thematic depth, often reflecting her progressive social views and spiritual beliefs. A strong feminist undercurrent runs through much of her work. While not always overtly political in the manner of suffragist banners, her paintings frequently explore themes of female confinement – both literal and metaphorical – and the quest for spiritual and intellectual liberation. Figures trapped behind bars, entangled in drapery, or weighed down by earthly concerns can be interpreted as critiques of the societal constraints placed upon women. Conversely, figures ascending towards light or breaking free represent female empowerment and self-realization.

Spiritualism and the concept of the soul's journey towards enlightenment are dominant themes. Works often depict the struggle between darkness and light, materialism and spirituality, despair and hope. The transition from one state to another is a frequent subject, visualized through figures moving from shadow into radiance, or through symbols of metamorphosis like butterflies or dawning light. This reflects the widespread Victorian interest in the afterlife and spiritual evolution, interests De Morgan shared deeply with her husband.

Later in her career, particularly during and after the First World War, pacifist themes became prominent. Horrified by the conflict, she produced powerful allegorical works condemning violence and mourning the loss of life, often using symbolic imagery to convey the spiritual devastation of war. These paintings stand as poignant artistic responses to the trauma of her time.

Representative Works: A Visual Legacy

Several key paintings exemplify Evelyn De Morgan's style and thematic concerns:

_Flora_ (c. 1894): This painting clearly shows the influence of Botticelli, particularly his _Primavera_ and _Birth of Venus_. Depicting the Roman goddess of flowers against a backdrop of a Florentine landscape, the work celebrates beauty, nature, and the arrival of spring. The meticulous rendering of flowers and the graceful linearity of the figure are characteristic of her style.

_Aurora Triumphans_ (1886): Meaning "Triumphant Dawn," this work allegorizes the victory of light over darkness. The figure of Aurora, the dawn goddess, rises majestically, banishing the shadowy figures of Night. The use of radiant colour and light powerfully conveys the theme of spiritual awakening and hope.

_Night and Sleep_ (1878): An earlier work, this painting depicts two draped female figures representing Night and her son Sleep, drifting over a darkened landscape. It showcases her ability to create evocative, dreamlike atmospheres and demonstrates her early engagement with allegorical personification, possibly influenced by figures like Michelangelo or contemporary sculptors.

_Earthbound_ (1897) and related studies (e.g., _Gold Composition of Figures for ‘Earthbound’_): This allegorical painting addresses the theme of materialism weighing down the human spirit. A richly dressed woman, laden with gold, is contrasted with figures striving towards a higher spiritual plane, highlighting the conflict between worldly possessions and spiritual aspiration. The preparatory studies reveal her careful compositional planning.

_The Hourglass_ (1904-05): A poignant meditation on the passage of time and mortality. A figure watches the sands drain through an hourglass, prompting reflection on life, death, and the potential for spiritual transcendence beyond the physical realm.

_S.O.S._ (c. 1914-1916): Created during the First World War, this painting is a powerful pacifist statement. A lone female figure, representing humanity or the soul, clings to a rock amidst a stormy sea, looking towards a faint glimmer of light – a spiritual S.O.S. It conveys despair but also a fragile hope for salvation from the deluge of war.

_Cassandra_ (1898): Depicting the Trojan priestess cursed to utter true prophecies that no one believes, this work can be seen as reflecting the frustration of unheard female voices or the burden of foresight. The intense emotion and dramatic composition are typical of De Morgan's narrative power.

_Helen of Troy_ (1898): Rather than focusing on the traditional narrative of the Trojan War, De Morgan portrays Helen contemplating a reflection of herself, suggesting themes of beauty, vanity, and the destructive consequences of desire. The rich colours and detailed background are characteristic.

Social Engagement and Literary Pursuits

Evelyn De Morgan's commitment to progressive causes extended beyond the symbolism in her paintings. She was an active participant in the social movements of her time. Notably, she was a signatory to the 1889 Declaration in Favour of Women's Suffrage, publicly aligning herself with the fight for women's right to vote. Her opposition to the conservative establishment is also evidenced by her refusal to submit works to the Royal Academy of Arts after her initial successes, choosing instead to exhibit primarily at alternative venues like the Grosvenor Gallery and the New Gallery.

Her social conscience also manifested in practical ways. She was involved with charitable work, including supporting mothers' groups in the impoverished East End of London and serving as the superintendent of a boarding school for underprivileged girls. These activities demonstrate a deep-seated concern for social justice and the welfare of women and children.

Furthermore, De Morgan possessed literary talents. She wrote short stories, poems, and plays, often exploring themes similar to those in her visual art. Her unpublished novel, Toy Gods, for instance, reportedly delves into issues of female self-restraint and societal expectations. This literary output provides another layer to understanding her intellectual and creative engagement with the world.

Later Years and Continued Vision

Evelyn De Morgan remained artistically productive throughout her life. The last fifteen years, following the turn of the century and encompassing the difficult period of the First World War, saw the creation of some of her most intensely spiritual and symbolically complex works. Her focus on themes of conflict, death, transformation, and spiritual transcendence deepened during this time.

William De Morgan passed away in 1917. Evelyn survived him by only two years, dying in London on May 2, 1919, at the age of 63. She was buried alongside her husband in Brookwood Cemetery, Surrey. Her later works stand as a testament to her enduring artistic vision and her continued grappling with the profound spiritual and existential questions that had animated her art throughout her career.

Legacy and Collections

Evelyn De Morgan left behind a significant body of work, comprising over one hundred oil paintings and a large number of drawings and studies. While her reputation waned somewhat in the decades immediately following her death, overshadowed by the rise of Modernism, there has been a resurgence of interest in her work since the late 20th century, particularly driven by feminist art history and a renewed appreciation for Victorian Symbolism.

She is now recognized as one of the most important female artists of her generation in Britain, admired for her technical skill, intellectual depth, and unique artistic voice. Her ability to blend Pre-Raphaelite aesthetics with Symbolist content, infused with her personal spiritualist and feminist convictions, marks her as a distinctive figure. Contemporary critics sometimes referred to her as perhaps the "first woman artist of the day," acknowledging her prominence.

Her legacy is preserved primarily through the De Morgan Foundation, which cares for a large collection of works by both Evelyn and William De Morgan. For many years, a dedicated museum existed, and the collection is now largely housed at the Watts Gallery – Artists' Village in Compton, Surrey, and Cannon Hall Museum in Barnsley, South Yorkshire, ensuring public access. Her works are also held in other public collections, including the British Museum in London, and various regional galleries in the UK, as well as private collections. Institutions like The Pre-Raphaelite Trust Inc. also play a role in the study and appreciation of artists from this period.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

Evelyn De Morgan's art offers a compelling window into the cultural, spiritual, and social preoccupations of the late Victorian and Edwardian eras. As a highly successful female artist in a field dominated by men, her career itself was a form of boundary-breaking. Her paintings, characterized by their luminous colour, meticulous detail, and profound symbolism, explore timeless themes of struggle, transformation, the conflict between the material and the spiritual, and the quest for enlightenment. Influenced by Renaissance masters like Botticelli and Pre-Raphaelite contemporaries like Burne-Jones, she forged a unique style that powerfully conveyed her feminist, pacifist, and spiritualist ideals. Today, her work continues to resonate, admired for its technical brilliance, its intellectual depth, and its visionary exploration of the human condition.