Martin Johann Schmidt, affectionately known as "Kremser Schmidt" due to his long association with the town of Krems an der Donau, stands as one of the most significant and prolific painters of the Austrian Late Baroque and Rococo periods. Active during the 18th century, his life and work bridged the dramatic intensity of the Baroque with the lighter sensibilities of the Rococo, leaving an indelible mark on the artistic landscape of Central Europe. His output was vast, encompassing grand altarpieces, intimate devotional images, mythological scenes, and insightful portraits, all rendered in a distinctive style that earned him widespread acclaim during his lifetime and continues to captivate audiences today.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in 1718 in Grafenwörth, a village near Krems in Lower Austria, Martin Johann Schmidt was immersed in an artistic environment from a young age. His father, Johannes Schmidt, was a sculptor, providing an early exposure to creative pursuits. While details of his earliest training are somewhat sparse, it is known that he received instruction from the painter Gottlieb Starmayr in nearby Dürnstein. This initial apprenticeship laid the foundation for his technical skills.

Unlike many prominent artists of his time who sought extensive academic training in major art centers like Vienna or Rome, Schmidt's formation was less conventional. He spent much of his formative period studying the works of earlier masters and contemporaries available to him in the rich monastic and church collections of Lower Austria. He settled relatively early, around 1740, in Stein an der Donau (now part of Krems), which would remain his home and primary base of operations for the rest of his long life, until his death in 1801. This deep connection to the region earned him the moniker "Kremser Schmidt."

His decision to remain based in Krems, rather than relocating permanently to the imperial capital Vienna, shaped his career. While he maintained connections with Vienna and received commissions from across the Habsburg lands, his identity remained firmly rooted in the Danube valley. This regional focus allowed him to develop a unique artistic voice, absorbing influences while cultivating a style that resonated deeply with local patrons, particularly the clergy and monastic orders.

The Artistic Milieu: Influences and Contemporaries

Schmidt emerged during a vibrant period in Austrian art. The High Baroque tradition, established by figures like Johann Michael Rottmayr, was evolving. Schmidt's direct predecessors and older contemporaries, whose work he undoubtedly knew, included the great fresco painters Paul Troger and Daniel Gran. Their dynamic compositions and mastery of light, particularly evident in the ceiling frescoes of Austrian monasteries and churches, formed part of the visual culture Schmidt absorbed.

However, Schmidt carved a distinct path, focusing primarily on easel painting and altarpieces rather than large-scale fresco cycles. His most significant Austrian contemporary was Franz Anton Maulbertsch, another towering figure of the Late Baroque/Rococo. While often mentioned together due to their prominence, their styles differed considerably. Maulbertsch's work is characterized by ecstatic visions, flickering light, and incredibly fluid, almost sketch-like brushwork. Schmidt, while dynamic, often displayed a greater solidity of form and a different approach to colour and light.

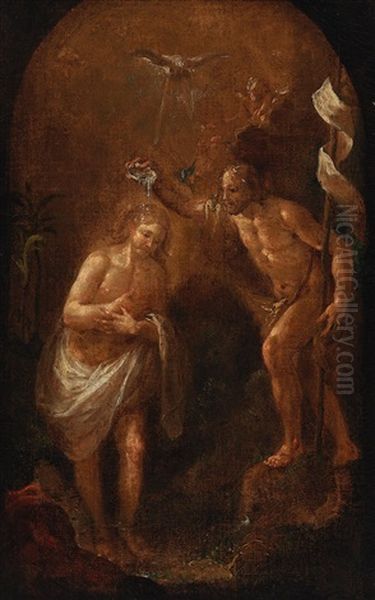

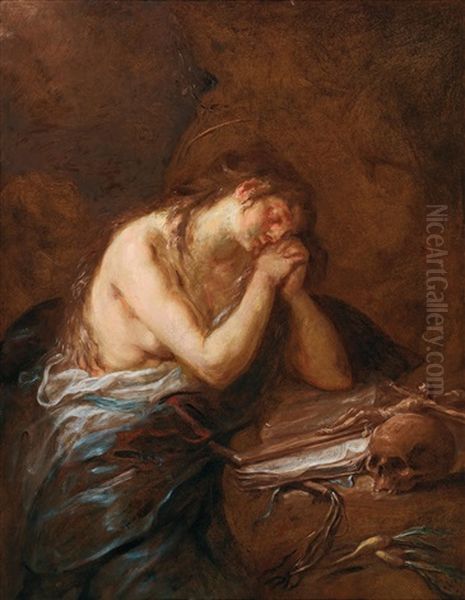

Beyond Austria, the influence of earlier masters is palpable in Schmidt's work. The most profound impact came from Rembrandt van Rijn. The Dutch master's dramatic use of chiaroscuro (strong contrasts between light and dark), his psychological depth in depicting figures, and his mastery of etching deeply resonated with Schmidt. This influence is evident throughout Schmidt's career, particularly in his handling of light in religious narratives and in his own accomplished work as an etcher.

Connections to Italian art, particularly North Italian and Venetian painting, are also apparent, especially after the mid-century. While direct travel to Italy is not definitively documented, the circulation of prints and paintings, and possibly a period of study or travel in his youth, likely exposed him to the works of artists like Giovanni Battista Tiepolo or Giovanni Battista Piazzetta. Their vibrant colour palettes and dynamic compositions may have contributed to the evolution of Schmidt's style towards greater brightness and fluidity in his later years. Echoes of the Flemish Baroque, particularly the richness of Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck, can also be discerned as part of the broader Baroque heritage he inherited.

Development of a Unique Style

Kremser Schmidt's artistic style was not static; it evolved significantly over his long career, synthesizing various influences into a highly personal and recognizable manner. His early works often exhibit a darker palette and a pronounced, Rembrandtesque chiaroscuro. Forms are solid, and the mood can be deeply introspective and dramatic, well-suited to the solemnity of religious subjects.

Around the 1750s and developing further into the 1770s, a noticeable shift occurred. While retaining the underlying Baroque sense of drama and emotional intensity, Schmidt's palette brightened considerably. He began employing more luminous, often cooler colours – blues, pinks, yellows, and light greens – applied with increasing freedom. His brushwork became looser and more visible, imbuing his surfaces with a vibrant texture and energy.

This later style successfully blends the gravitas of the Baroque with the elegance and lightness characteristic of the Rococo. Figures retain their emotional weight, but the overall impression is often more airy and graceful. Some art historians have noted the forward-looking aspects of his later technique, particularly the free handling of paint and the atmospheric effects of light, suggesting tendencies that foreshadow aspects of Romanticism or even, in their painterly freedom, hint at approaches explored much later by Impressionists, though such connections should be made cautiously.

He masterfully adapted his style to suit the subject matter and the intended setting. Grand altarpieces often feature dynamic, multi-figured compositions with swirling drapery and expressive gestures, designed to inspire awe from a distance. Smaller devotional paintings might display a quieter intimacy, focusing on tender expressions and subtle interplay of light. His mythological scenes allowed for a more playful or sensual interpretation, often showcasing the Rococo gracefulness.

Subject Matter and Major Commissions

The vast majority of Kremser Schmidt's oeuvre consists of religious paintings. He was the preferred painter for countless churches, chapels, and monasteries throughout Lower Austria and beyond, including commissions in Vienna, Styria, Bohemia, Moravia, and Hungary. His deep understanding of Catholic iconography and his ability to convey spiritual narratives with emotional resonance made him highly sought after by ecclesiastical patrons.

His religious works include numerous large-scale high altarpieces, such as the one completed in 1750 for the St. Nicholas Parish Church in his home town of Stein. He painted countless side altarpieces, depictions of the Virgin Mary, Saints, biblical scenes (like The Last Judgment), and works illustrating the lives of Christ and the Apostles. Notable examples can be found in major Austrian monastic centers like Göttweig Abbey and Seitenstetten Abbey, as well as in the Cathedral of St. Pölten.

While religion dominated his output, Schmidt was also adept at secular themes. He produced mythological and allegorical paintings, often drawing from Greco-Roman antiquity. These works allowed him to explore different moods and compositions, often incorporating elegant figures and lush settings typical of the Rococo sensibility. He also painted genre scenes and portraits, although these form a smaller part of his work. His Self-Portrait from 1762 (Historisches Museum Krems) offers a glimpse of the artist himself, while works like The Painter and his Family provide insights into his personal life and the broader social context.

His representative works are numerous, but key examples often cited include the aforementioned Self-Portrait (1762), The Apostle Andrew (1775, Belvedere, Vienna), the high altar painting for St. Nicholas Church in Stein (1750), and various versions of The Adoration of the Shepherds or The Assumption of the Virgin. Each showcases his characteristic blend of dynamic composition, expressive figures, and distinctive handling of light and colour.

Mastery of Etching

Beyond his prolific output as a painter, Martin Johann Schmidt was also a highly accomplished etcher. He produced a significant body of graphic work, translating many of his painted compositions into prints and creating original designs specifically for the medium. His etchings demonstrate the same mastery of light and shadow evident in his paintings, heavily influenced by Rembrandt's graphic work.

Schmidt's etchings often feature rich tonal variations, achieved through dense cross-hatching and skilled manipulation of the etching needle. Subjects range from religious scenes and depictions of saints to genre figures and character studies. These prints played a crucial role in disseminating his artistic ideas and compositions to a wider audience, further cementing his reputation across Central Europe. His technical skill and artistic sensitivity place him among the foremost Austrian printmakers of the 18th century. The accessibility of prints also helped to popularize his style beyond the confines of church and palace walls.

Recognition and Later Life

Despite not following the traditional academic path centered on the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts (Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien) in his youth, Schmidt's talent and growing reputation could not be ignored. In 1768, he was formally accepted as a member of the Academy. This official recognition acknowledged his status as one of the leading artists in the Habsburg lands, even though he continued to reside and work primarily in Stein.

His membership in the Academy solidified his position within the artistic establishment, although he remained somewhat independent compared to Vienna-based contemporaries. He continued to be incredibly productive throughout his later years, receiving commissions well into his old age. His workshop in Stein was likely a busy place, possibly employing assistants to help manage the large volume of work, particularly for major altarpiece projects.

His popularity endured across different social strata. His works were appreciated not only by the clergy and aristocracy but also by the burgeoning middle class. His ability to combine artistic sophistication with genuine piety and relatable human emotion contributed to his broad appeal. Martin Johann Schmidt died in Stein an der Donau in 1801, at the venerable age of 83, leaving behind a vast and influential body of work.

Legacy and Importance

Martin Johann Schmidt, "Kremser Schmidt," remains a pivotal figure in Austrian art history. He represents the culmination of the native Baroque tradition, infused with the elegance of the Rococo and marked by his unique personal style, particularly his distinctive use of colour and light. His deep connection to the Krems region makes him a vital figure in local cultural identity, celebrated in the museum bearing his name (presumably the museum in Krems).

His legacy lies in the sheer quality and quantity of his output, which adorns countless churches and collections, primarily in Austria but also in neighboring countries. He successfully navigated the transition between major artistic styles, creating works that possess both the dramatic power of the Baroque and the refined grace of the Rococo. His influence extended through his prints and potentially through pupils or workshop assistants, shaping religious art in the region for decades.

While perhaps less internationally famous than some Italian or French contemporaries like Tiepolo, Antoine Watteau, or François Boucher, Kremser Schmidt holds a position of paramount importance within the Central European context. His art offers a unique window into the religious and cultural life of the Habsburg Empire during the latter half of the 18th century. Today, his works are prized possessions in museums like the Belvedere in Vienna and the Historisches Museum in Krems, and many remain in the churches and monasteries for which they were originally created, continuing to fulfill their devotional purpose while being admired for their outstanding artistic merit. He stands as a testament to the enduring power of faith-inspired art and the unique genius of Austria's Late Baroque master.